Introduction

First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Peoples in Canada face significant inequities in health and access to health care, impacted by colonization, continued colonialism, and racism including systematic suppression of Indigenous languages, health knowledge, and healing practices1-3. Essential rehabilitation services common in urban settings are not readily available in rural and remote Indigenous communities generally and in Northwestern Ontario specifically4. Indigenous elders aged over 75 years are 45–55% more frail than the average senior in Ontario5. This often forces Indigenous elders to leave their home communities and support systems to receive specialised care in urban centers6. However, the care accessible in urban centers is generally not provided in the first language of most Indigenous elders7,8.

Other regions in Canada9,10 (Reinikka K, Ferris C, pers. Comm., 2019) and internationally11-17 facing similar inequity and access challenges have successfully used community-based therapy assistant models to support people in need of rehabilitation or living with disability.

Literature review

The sparse literature on the topic highlights the existing need for community-based assistant programs in rural, remote, and often Indigenous regions across the globe including South Africa11, India16, Australia13-15,18-20, Solomon Islands17, Alaska21, and Nunavut22,23. It also highlights the need for community health worker assistance to span diverse areas of health care such as chronic disease care15,21,24,25, nutrition22, midwifery23, and rehabilitation11,17. Previous community-based assistant programs identified both challenges and facilitators to success.

Challenges included time constraints due to personal conflicts or workload22,26-29; infrastructure barriers within communities18,24,26; technological difficulties, including poor internet access and/or limited technology21,22,26; financial costs to the community11; marketing, promotion, and knowledge of the program18; lack of language support22; and participants having varying education levels15,20.

Facilitators included visuals, interactive activities, language, and data related to community geography20,21,30; encouraging empowerment by actively involving community participants in program development11,13-15,19,30; inclusion of personal stories and life experiences from individuals in the community21,26; receiving accreditation for learning20,25,31; and mentorship opportunities during training26.

Programs focusing on rehabilitation specifically highlighted the importance of addressing disability from a social determinants of health point of view11; leveraging community resources for sustainable, locally appropriate disability services13; partnership between locally trained community workers and external health service teams13,14; and accounting for the emotional and financial stressors from loved ones affected by health burdens16,29.

Programs focusing on training local Indigenous community members specifically highlighted the need for locally and culturally appropriate content14-16,20,21,26,30, tailoring the program delivery and content to community barriers/enablers31, including cultural safety training28, and generic programs covering a broad base of skills32 and viewing relationships between the individual, community, and wider context as interrelated factors on health33,34. Indigenous-focused programs also advocated for specific approaches to learning where teaching methods align with Indigenous pedagogies that allow the voices of Indigenous peoples to be heard through culture-centered and self-determined ways21,27,33, and employ modified ways to support and measure teaching effectiveness for Indigenous workers26.

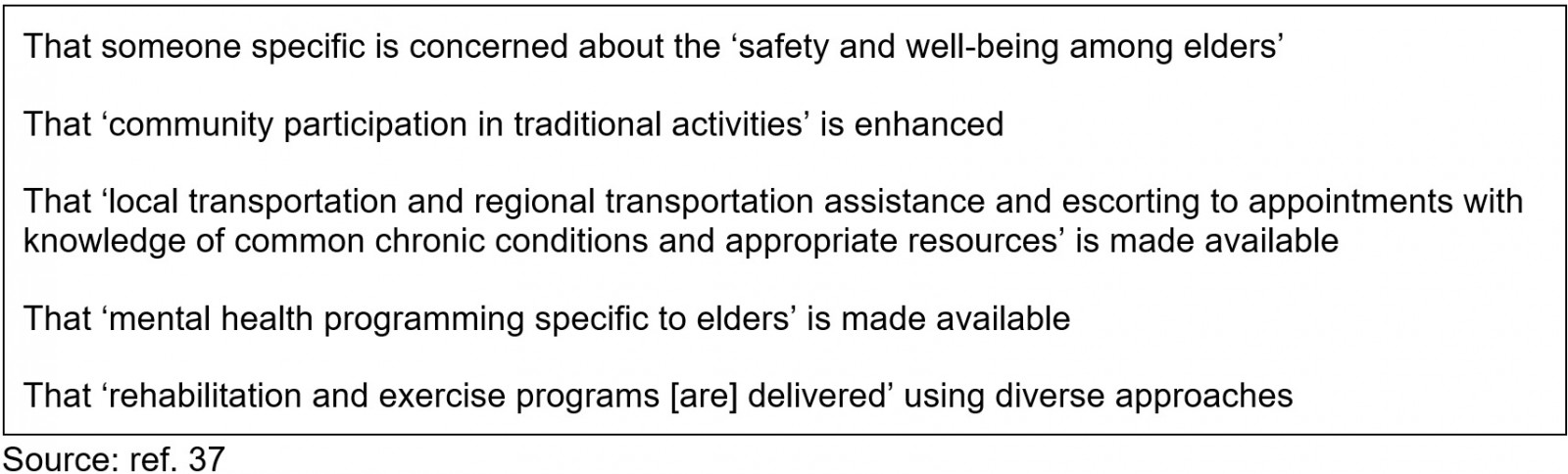

Additionally, two community engagement projects led by Taylor35,36, including First Nations partners, confirmed a desire and need for the Community Rehabilitation Worker (CRW) role in supporting and enhancing elders’ health, wellbeing, and ability to age in place. In alignment with the literature review, the needs assessment identified five common themes (facilitators) that would need to be addressed in order to maintain and improve the health, wellbeing, independence, and ability to age in community of First Nations elders in the four communities (Box 1).

In response, our collaborative team sought and received funding from the Canadian Frailty Network to simultaneously develop and evaluate a CRW program using a community-based participatory action research model37.

With guidance from the First Nations, in this manuscript ‘elder’ (lowercase ‘e’) is inclusive of those in the community aged approximately more than 55 years, and ‘Elder’ (uppercase ‘E’) is an honourable status bestowed upon an individual by their community to honour their knowledge, wisdom and earned respect. Both terms will be used as most appropriate, and sometimes elders include Elders.

Box 1: Themes from the Community Rehabilitation Worker needs assessment

Research goals and objectives

With the long-term goals of improving equity in access to quality, culturally safe rehabilitative care; building capacity in Indigenous communities by increasing the number of Indigenous professionals working in healthcare; and affirming Indigenous peoples’ inherent right to self-determination as called for by the Truth and Reconciliation Committee3, particularly Calls 19, 22 and 23, our objectives were to:

- develop a community-informed, culturally appropriate curriculum for training First Nations community members in the CRW role to provide rehabilitation support in their participating communities

- iteratively evaluate the CRW curriculum from the perspective of the potential learners, First Nations Elders, Home Care (potential CRW) clients and their family/caregivers, community healthcare workers, and rehabilitation professionals working with Indigenous populations across Canada

- develop program and policy recommendations regarding the CRW role aligning with community values and needs.

Findings from the literature review and the community needs assessment were incorporated into the curriculum. This article discusses the findings from the iterative evaluation of the CRW program development, curricular adaptations, and possible implications for the development of future community-based health worker programs.

Methods

Building on existing partnerships, this interdisciplinary and intersectoral project was a collaboration between four First Nations in treaty territories 5 and 9 (Sandy Lake, Eabametoong, Michikan Sakahegun, and North Caribou Lake First Nations); rehabilitation leaders from St Joseph’s Care Group, Northwestern Ontario Regional Stroke Network, Windigo Tribal Council, Sioux Lookout First Nation Health Authority, and Indigenous Services Canada – Home and Community Care – Ontario Branch; Lakehead University; and Confederation College.

Using a mixed-methods, community-based participatory action research model37, the project aligned with the OCAP® (Ownership, Control, Access, and Possession) framework for working with Indigenous populations38. Community partners were active participants in all parts of the program development and research processes including applying for funding, developing the project, conducting the research, analysing the findings, and adapting the CRW curriculum accordingly.

Ownership: During the development of the project, it was agreed that all project partners own the research data and program resulting from this project while Lakehead University houses the research data. Allowing Lakehead University to house the data is a form of ‘stewardship’ and ‘is a mechanism through which ownership may be maintained [by the project partners]’38.

Control: An advisory committee guided and mentored the project. Members included the health directors, Home and Community Care coordinators, care providers (nurses and physicians), Elders, and a representative of the Nishnawbe Aski Nation Health Transformation team. Recommendations regarding curriculum modules or evaluation processes were implemented as soon as consensus was achieved among project partners and the advisory committee.

Data access and possession: The four partner communities represented by the four health directors (Garth Wesley Nothing (Wes), Joan Rae, Robert Baxter and Marlene Quequish), St Joseph’s Care Group (represented by Denise Taylor) and Lakehead University (represented by Helle Møller) own the data collectively. All agreed that Lakehead University would house the raw data due to their available infrastructure, and that all partner representatives would have the right to access the data at any time.

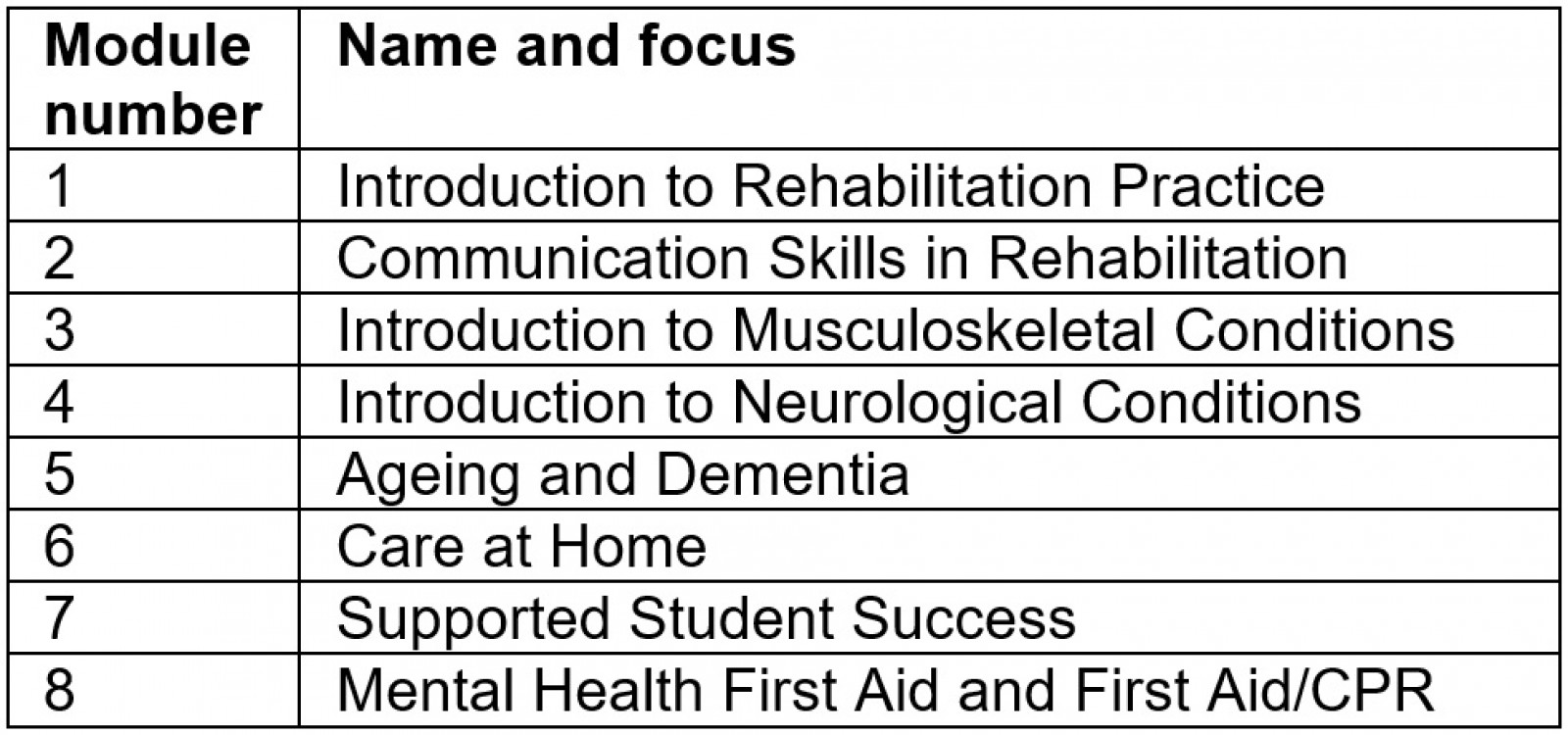

Evaluation was completed on the six CRW curriculum modules that were developed by the project team (Table 1). Content for module 7 (Supported Student Success) will be determined by students and the Home and Community Care coordinators after completion of the first six modules, and module 8 (Mental Health First Aid and First Aid/CPR) is standardized training. Modules will be delivered once per month and are 1 week in duration. Between each module, the CRW students will complete a practical placement within their local Home and Community Care programs, supervised by the Home and Community Care coordinator.

Qualitative and quantitative methods that First Nations partners viewed as culturally acceptable were used to assess the content and delivery of curriculum modules. Community, health system and academic partners collaboratively developed an interview guide39 for individual/focus group interviews/sharing circles, and a survey. Items were based on the needs assessment (Box 1)37 and previously validated interview guides for similar evaluations10,40. Objectives were to assess congruency in module objectives, content, methods, and incorporation of local First Nations culture, languages, and traditions. All participants were informed about all aspects of the research in writing, and interview participants were also informed face-to-face. Signing an interview consent form and responding to the survey were described as consent to participate. Surveys and interview schedules are available upon request.

Table 1: Community Rehabilitation Worker curriculum in eight modules

Survey

Surveys were used to elicit opinions on the curriculum from rehabilitation professionals throughout Northwestern Ontario and across Canada who work with Indigenous communities. A total of four surveys were sent out to evaluate six learning modules. The first two surveys included two modules; the last two included one each. Each survey had 25 questions, with all questions appearing across all four surveys. Open-ended questions appeared below Likert-type or yes/no questions, allowing participants to expand upon their answer and provide additional feedback and suggestions. At the end, participants were asked to share any other comments, suggestions, or recommendations about any instructional activities, methods, materials, or resources.

Survey recruitment: Invitations to participate in the surveys, a survey link, and the module to review were sent by email to the following listservs: North Western Ontario Regional Rehabilitative Care Program email distribution list; pan-Canada Rehabilitation Support Worker Collaborative; St Joseph’s Care Group Quality Practice Councils for Physiotherapy, Occupational Therapy, and Speech Language Pathology; and the Home and Community Care coordinators in each community. Surveys were responded to online via the Redcap® platform.

Survey analysis: All questions in all surveys were analysed. Each survey was scored individually, responses for each survey question across all surveys were averaged, and descriptive statistics were used to determine average and total response characteristics. Results were used to refine the module in question and inform the development of subsequent modules.

Individual and focus group interviews

Individual and focus group interviews were conducted to garner perspectives from First Nations community elders and other potential CRW clients, their families, potential CRW students, community health professionals and workers. The individual and focus group interview schedule included the same queries as the survey but in an open-ended format. Based on the feedback from the first round, with approval from the advisory committee, subsequent interview/focus group/talking circle guides were shortened and modified to include lay terms and a video summary. As well, audio recordings of the evaluation instruments, participation information, and consent forms were translated into OjiCree and Ojibway.

Recruitment: For individual or focus group interviews/talking circles, the team recruited from each community four to six First Nations elders with rehabilitation needs, four to six family members (or caregivers) of elders with rehabilitation needs, two to six First Nations potential learners, and two to four other healthcare professionals and workers. Recruitment took place by phone call, email, or in-person visit (if COVID-19 protocols allowed). As discussed with First Nations partner representatives, to honour already established relationships and Indigenous methodologies, invitations were not scripted.

Procedures: Focus groups and interviews were either audio-recorded or documented by note- taking, with permission of participants. Due to the complexities presented by the COVID-19 pandemic, the project team only requested one community’s participation in the qualitative evaluation of each module to decrease the burden placed on any community or individual participant. Each First Nation determined if the research team was permitted to enter the community to conduct research. If not permitted due to COVID-19, the research team gave local community health members written and video versions of a summary of the modules, information letters and consent forms, and the survey and interview guides. If requested, the video summary, information letter, consent form, and interview guides were provided in the local First Nation language. Following local First Nation practices, all interview participants were provided a light meal and a small gift to show gratitude for their contributions.

Interview analysis: All audio-recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim, and interview notes were transcribed and later expanded. The team used a thematic network analysis to organise findings into basic, organising, and global themes. Basic themes are represented by segments of the original text or quotations41. ‘The organizing themes represent related clusters of quotations, and the global themes are a way to synthesize the lower groupings’ (p. 17)42. Reliability was ensured through intercoder agreement, which involved two team members (HM, DT) reading, coding, and analysing interview transcripts and notes over several iterations and that findings, including basic, organizing, and global themes along with a preliminary analysis, were presented to the advisory committee and project team for feedback and final analysis.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for the research part of the project was sought (and received) through Lakehead University Research Ethics Board (REB) #1469055, St. Joseph’s Care Group REB #2020008, and Confederation College REB #0091. All procedures were made in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

As curriculum development in a community-based research setting is iterative, the process occurred over a span of 10 months (September 2020 to July 2021). Data gathering, analysis of results, and reporting to the communities and advisory committee occurred between January and November 2021.

Participants

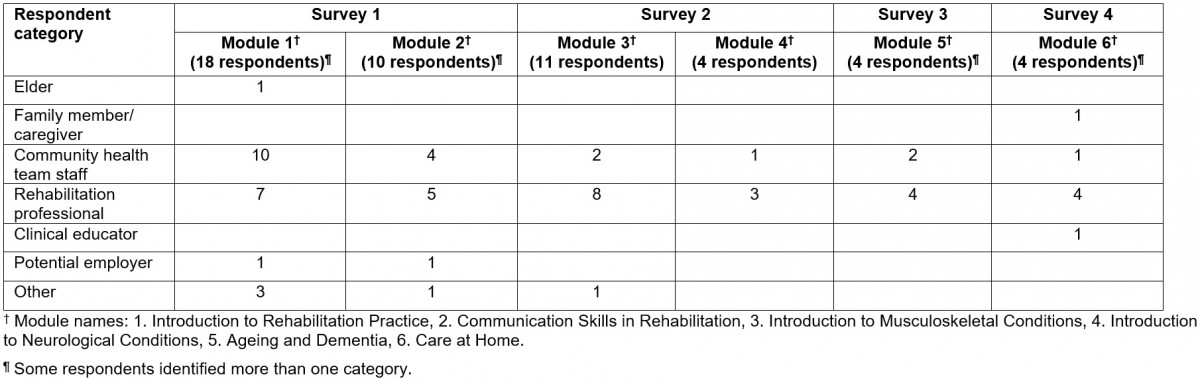

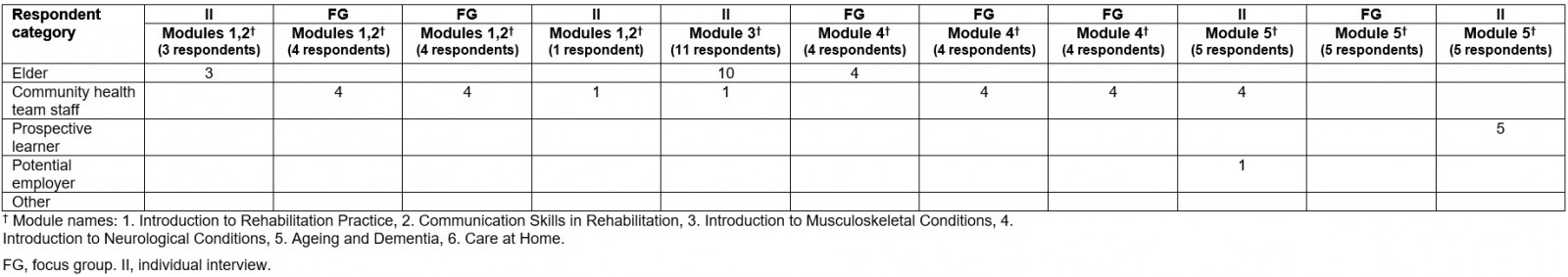

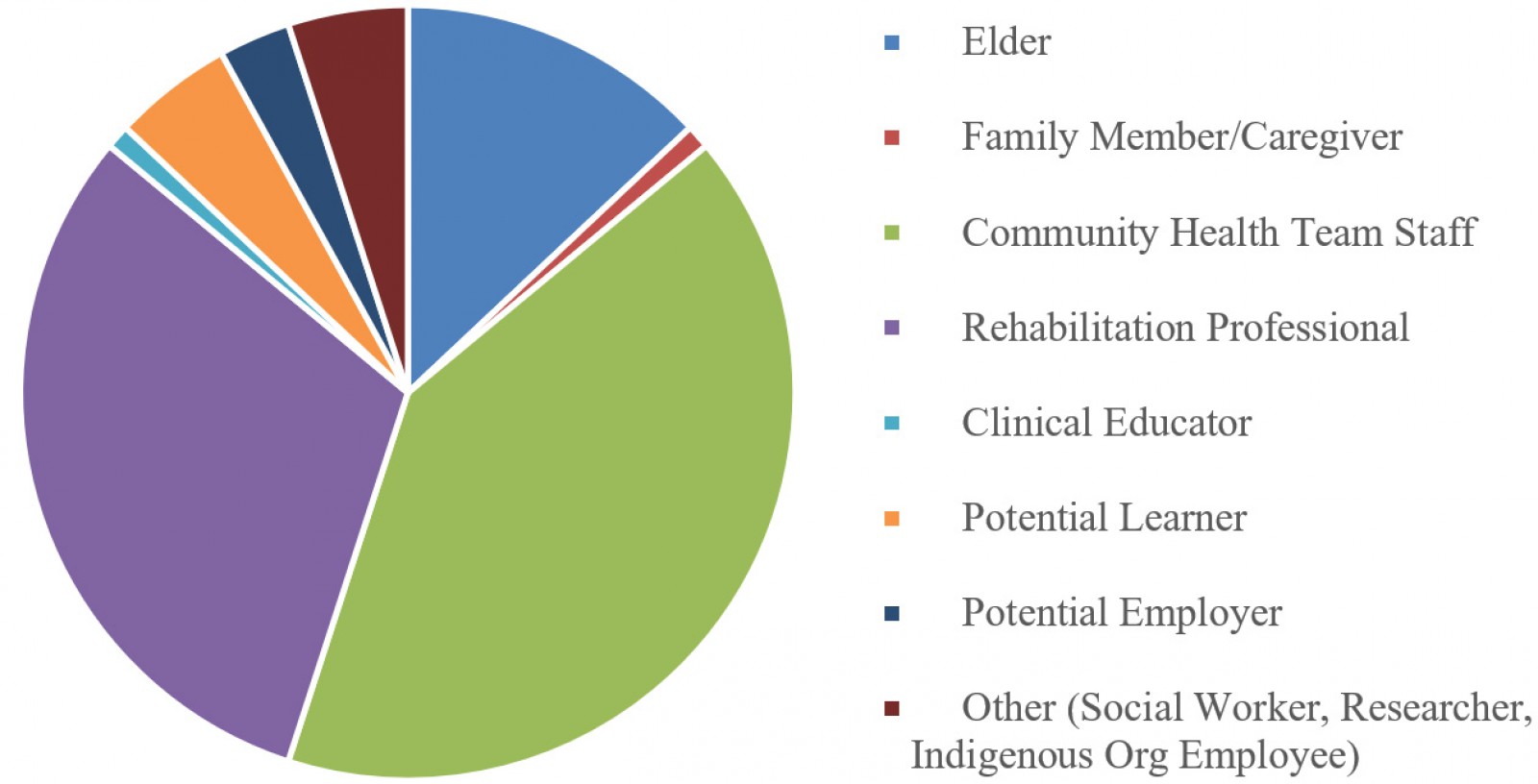

Surveys were received from 51 people, including rehabilitation professionals, community health team staff, and potential learners. For a full summary of the demographics and participant characteristics for the survey, see Table 2 and Figure 1. For the focus group/talking circles, there were 25 First Nations community members comprising elders/Elders, potential learners, and community health care workers. Twenty-five elders/Elders participated in individual interviews. The advisory committee attended five committee meetings where modules as well as survey and individual interview/focus group/talking circle feedback from the first six modules were discussed (Table 3). Quotes are reported from surveys (S), interviews (IT), focus groups (FG) and from survey interviews (SI). During survey interviews participants provided in-person responses to the survey questions as a group rather than responding individually to a written survey online. The responses were not recorded but notes were taken. The session number is also reported; for example, FG1 indicates data collected during the first focus group and S1 indicates collection from the first survey.

Table 2: Demographic information for survey respondents

Table 3: Demographic information for interview and focus group respondents

Figure 1: Demographic distribution of all survey participants.

Figure 1: Demographic distribution of all survey participants.

Results from survey evaluation

In general, participants felt that (1) learning modules accurately reflected the learning objectives outlined in each module; (2) timeline to complete modules was realistic and instructional materials, and activities and resources for the modules were appropriate and clear; (3) evaluation activities accurately measured student learning; and (4) learning modules reflected Indigenous culture (as rated only by participants who identified as Indigenous). When asked if they recommended any other instructional, methods, or evaluation activities, the majority of participants reported they did not.

In the survey, open-ended questions followed each Likert-type question where participants could expand their feedback. Based on this feedback, modules were updated. Specific suggestions included defining additional terms, adding consent information, and ensuring client safety. These simple suggestions were adopted in the final versions of the learning modules. A very practical suggestion by survey participant 1 (S1) was, ‘Travel schedule not realistic. Monday is travel until 2:30. Travel Sunday’. Based on this, the recommended schedule of community visits was adapted.

Adapting the module contents to be more hands-on emerged as a theme in participants’ open-ended suggestions and comments. Suggestions comprised including experiential learning opportunities (S2), focusing on practical experience with patients with dementia (S3) and/or rehabilitation needs (S2), increasing time to practice new skills (S3), and introducing diverse teaching delivery (inclusion of artistic or visual elements to module assignments, self-reflection, group presentations, and more) (S1). As a result, many of the instructional materials, resources, and evaluation activities have an interactive, experiential focus.

Several participants noted there was a large volume of material to be covered in the curriculum. To mitigate this, some suggested that learners ‘should have more exercises or class tests or question answers’ (S2) or ‘more Multiple Choice Question tests’ (S2) to assess comprehension. To further encourage participant autonomy, a subtheme suggested ‘flexible time frames’ (S1), ‘choice in assignments’ (S1), and a need to have CRW learners feel supported in the role (S2).

In terms of the cultural components incorporated after the first module review, participants noted the sections were ‘content heavy [therefore] limiting understanding by non-English speakers’ and that translation into OjiCree would be helpful (S1). For further cultural enhancement, it was suggested that other instructional activities could include the ‘Medicine wheel and 7 Grandfather Teachings’ (S1), the ‘How to Do a Circle DVD’ (S1), and ‘Elder–youth pair-up to practice language’ (S1). Additionally and importantly, one participant stated:

We often assume that Indigenous community members understand and are privy to the history and impacts of colonialism on health; however, we also benefit from education in this area. I wonder if cultural safety/competence training (i.e. San’yas) would be of benefit for these CRWs and their clinical supervisors. (S3)

The iterative nature of the project allowed the modules to be adapted based on feedback from all participants. For example, it was suggested in feedback from Module 1 (Introduction to Rehabilitation Practice) that there should be ‘more pictures and less words’ (S1) and from Module 2 (Communication Skills in Rehabilitation) that there could be ‘pictures of exercises for elders to follow’ (S1). Thus, subsequent modules were updated to include more visuals and culturally relevant pictures. On review of Module 5 (Ageing and Dementia), after changes had been made, participant S3 noted, ‘Very good module! The different visuals are great, love the focus on kindness and respect, love including caregivers! Well done!’

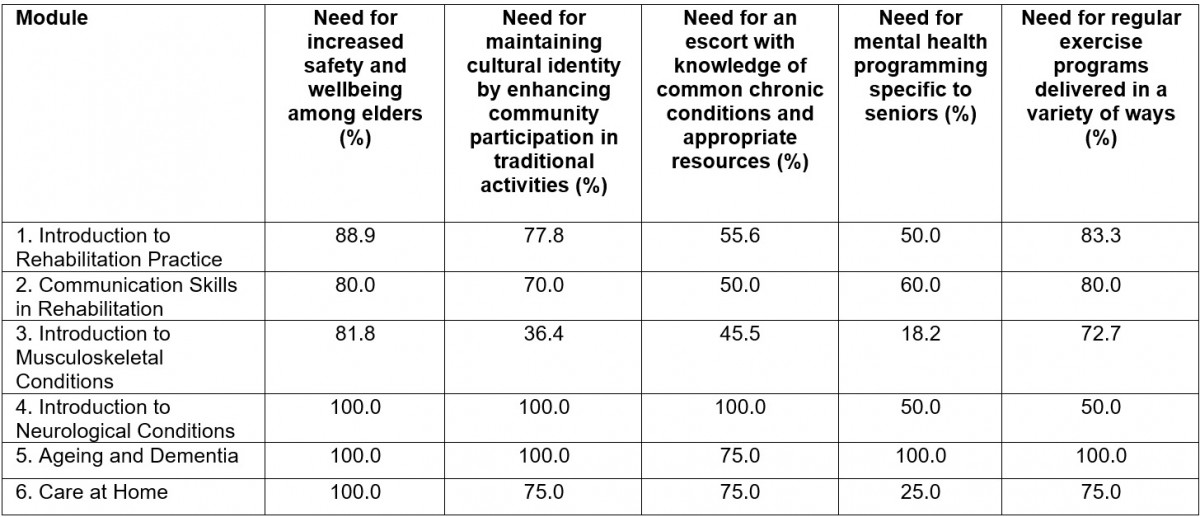

The review also included an evaluation of how the module incorporated or emphasized the needs of the community. Participants assessed whether each module supported the five community-identified needs (shown in Table 4 as a percentage of responses). Overall, it was felt by the majority of Participants that learning modules did meet the community needs. The need for mental health programming specific to First Nations elders was the least supported, on average, with the learning modules: one participant noted in the open-ended question that ‘the focus on mental health in this module [Introduction to Musculoskeletal Conditions] was minimal’ (S2). Thus, a specific focus was placed on mental health and mental health supports within module 3 (Introduction to Musculoskeletal Conditions), and information on mental health resources has been prioritized throughout the curriculum. This includes dedicating the eighth module to Mental Health First Aid for Indigenous People in addition to Standard First Aid and Cardio-Pulmonary Resuscitation.

Table 4: Percentage of respondents from each module that support community-identified needs

Themes generated from interviews and open-ended survey responses

The themes that emerged from the open-ended survey questions and the individual and group interviews identified a critical need to include culture/tradition/spirituality/teachings, language revitalization, and community re-engagement/re-integration throughout the training program. Inclusion of such content provides First Nations elders, other potential CRW clients, their family members, learners, and care providers the ability to teach, learn, provide, and receive essential and culturally safe rehabilitative services in their home communities. Each of these themes is discussed below, and accompanying quotes from interview (IT), survey (SI) and focus group (FG) participants are included.

Culture, tradition, spirituality, religion: The project recognizes that all communities and individual community members interpret tradition, and what are considered traditional activities, differently and also that communities have varying approaches to spirituality and religion. However, many participants emphasized that culture and tradition should be part of the program. In particular, First Nations Elders saw a need to be able to connect with CRWs through language, tradition, and culture in their rehabilitation efforts as well as with children and youth in a similar fashion. It was suggested that, as part of their rehabilitation efforts, First Nations elders could support the reintegration of culture into community life.

It’s better to just … sit with [the elders], talk to them, ask questions. Just always ask them of their stories … That’s what we used to do, tell stories … I miss that. (IT4)

The elders, they have so much … to say to the young people … when you get older you need to talk to the young people … when you get older you are ready to talk to the young people about what life was all about. (IT1)

First Nations Elder participants envisioned that CRWs could engage with the elders around various activities – mostly traditional (and spiritual) including gathering traditional medicines, fishing, preparing and smoking fish, and participating in picnics and camp-outs. Such activities were considered to be important for both physical activity and mental health, and gave respect to First Nations Elders and knowledge-keepers. Engaging with First Nations elders during less traditional activities such as drives or boat rides or watching a baseball game were also suggested.

You should pray at the beginning and at the end of the module. To pray for guidance and for the blessing. (SI1)

I want the workers to see what elders are doing and be able to do the same. (FG4)

Do and [learn] how elders live in the past such as food, way of life, Indian medicine for diarrhoea etc. (FG5)

First Nations Elders expressed a need to be heard and valued more than they currently are. They asked that their knowledge should be shared and learning about culture, tradition, and language should be part of activities and assignments. People’s perceptions of engagement activities differ, however, and not all individuals or communities have the same approach to traditionality and spirituality.

In order to address these desires, the final curriculum now includes assignments in which students participate with First Nations elders in a traditional activity and a community activity as part of their rehabilitation engagement. Also included is the creation of a Memory Box by students and engagement in a reminiscing session with a First Nations elder. Lastly, modules are co-taught with an Elder, and students spend a half-day during each module discussing language and cultural resources and questions, addressing the desire for more local language inclusion. Lastly, the need for continuous funding, to be able to offer expanded and continuing education opportunities for CRWs, was raised.

Language: The interviews and focus groups with First Nations elders in particular highlighted the perception that the communities have unmet needs in relation to mastery of local languages. The elders suggested teaching the children and youth their language as part of activities (even by just visiting and being encouraged to listen to the elders and their stories).

Our language, that’s what the young people has to learn. The Indian language – to get their own language back … They got to learn the sayings, their own stuff … Cause it is very, very important to have our language back, cause a lot of things they don’t understand. (IT4)

I would want someone to speak Native so I can understand better. (FG3)

First Nations Elders, but also potential students and health professionals, were adamant about the use of traditional language as part of being supported by the CRWs. These desires posed challenges, as the consequences of colonization and continued colonialism have led to many Indigenous peoples not speaking languages most familiar to elders in the community.

In order to honor this feedback, the modules are co-taught with a First Nations Elder who speaks a local language, with a half-day dedicated to language and culture as noted above, guided by the students’ needs and learning. The development of a rehabilitation dictionary in OjiCree and Ojibway is in the planning stage, and key physiology and rehabilitation words that are part of the curriculum have been translated into OjiCree and Ojibway syllabics.

Community re-engagement/re-integration: The desire for inclusion of culture, tradition, spirituality, religion, and language was interconnected with the desire for elders to be integrated into the community. Many of the elders talked about not feeling part of their community because of not being able to participate in activities in their community, and suggested that, as part of rehabilitation, they be accompanied to community gatherings and to participate in children’s learning by being at the schools.

I would like a day trip by boat and see the nature out there. Also go for a picnic. (FG3)

Now when I am older, …[what] my dad told me, those messages are coming back to me and I want to share those messages with the young people. (IT1)

To address this feedback, the curriculum was adapted to ensure that transfers and mobility training sessions are realistic, with the practice being done both indoors and outdoors, on flat and rough ground, and on steep ramps, etc. Additional assignments were added to the curriculum to have students connect with rehabilitation care professionals who serve their community, to give them the skills needed to participate in cultural and community activities with Elders.

First Nations elders, their family members, and community healthcare providers also highlighted a need to provide dedicated funding and address existing inequities between rehabilitation and other resources available in urban Northwestern Ontario to support the mobility, health and wellbeing, and overall quality of life, of First Nations elders. These inequities were similar to some of the key themes noted in Taylor et al’s needs assessment36, namely mental health support and transportation options for First Nations elders (discussed above); one new theme – spaces for elders to gather – was also identified.

Mental health support specific for First Nations Elders: Some Elders spoke to their realities of experiencing colonization and having been residential school survivors, and the impact of this on their health and wellbeing:

When I stay inside two or three days inside my house, I couldn’t do anything … just think about what … when I went to residential school. Everything come back to me. Like what they did to you over there … I need counselling about … what happened [in residential school]… I need someone to tell me why … it really hurts sometimes. (IT1)

Need for local and regional transportation assistance: Another barrier to participation in community activities and gatherings was a lack of transportation. In urban Northwestern Ontario, accessible transportation for seniors, elders and people with mobility challenges and public transit is available in larger towns. However, these services are not always available in First Nations. As noted by one elder (FG1), an ‘elders’ bus would be great – needs to be accessible, for transportation’. However, another (FG2) reported ‘an issue with driver’s licences’, explaining that it is not easy to obtain a licence in remote communities.

Options for elders to gather in community: Places to gather for elders, which in urban Northwestern Ontario are provided via access to seniors’ centers and/or other community centers, was also raised as a need in First Nations. Although most First Nations have churches, gathering in such locations was not an option for some First Nations elders, because of negative associations with such places. ‘Space [to gather] is an issue for groups and also within the elders’ homes’ (FG1). With this in mind, it was recommended that:

Gathering with the elders or something … would take their mind [off] their problems and stuff … There’s a new building that came up … that’s geared for children though. It’s really nice … Maybe the elders could use it … they could go sometimes together over there … benches would be nice there cause the elders get tired easy … so being able to sit comfortably in a chair or something. (IT2)

The old people come to my house every day. To play bingo … they can talk to whom-ever they want to talk to … when they come here they talk about everything … [we speak in our language]. (IT1)

Discussion

The need to include components of language revitalization, culture and tradition, spirituality and religion, and community re-engagement and re-integration, throughout the training program was a key project finding. Although focused on First Nations communities in Northwestern Ontario, the findings from this project may be relevant to other rural and remote areas of the world that experience inequities in access to healthcare services generally, and rehabilitative services specifically, and wish to pursue community-based programs as a solution. In addition to areas where community-based rehabilitation service programs already exist, as discussed in the literature review, this could include other regions of North and Latin America43, Africa44, Asia45, Australasia and northern parts of Europe and Russia.

While little literature on rehabilitative programs speaks to this, existing literature on Indigenous health from Australia, Canada, the US and Aotearoa New Zealand46 concludes that connection to place, land, country3,47-51, culture3,47,50, and language3,50,52,53 are all strong factors in the maintenance and improvement of health and wellbeing.

In addition to being important for health and wellbeing, elements of culture and language are also key components in Indigenous-focused education nationally and internationally54. For example, providing a North American context through the seminal article ‘What matters in indigenous education: implementing a vision committed to holism, diversity and engagement’51, Toulouse cites Lee55 and stresses that Indigenous pedagogy is about ‘fostering identity, facilitating wellbeing, connecting to land, honouring language, infusing [content] with teachings and recognizing the inherent right to self-determination’ (p. 1). These sentiments are echoed by other North American Indigenous scholars and government entities56,57 as well as global Indigenous organizations58. While we acknowledge that Indigenous groups are different, several commonalities in relation to favored pedagogical strategies appear to exist. These include connection to culture, real life experiences, and experiential land-based activities59,60. Commonly reported in a North American context is also that teachings should be delivered with concrete-to-abstract and abstract-to-concrete examples, mini-lessons with hands-on activities, informal group talks59,60, different styles of instruction and assessment59-61, and the use of humor59,60,62. Given the emergence of commonalities between this work and past work, it is suggested that programs for rural and remote communities are based on the local language, culture and tradition of the area that allows for maximal community engagement.

Regarding community re-integration, it is also not surprising that a need for specific elder-focused mental health and transportation supports were common themes in interviews. Mental health services specific to Indigenous peoples have been called for by several Canadian Indigenous groups and scholars3,50,63 as well as internationally61 in order to address the impacts of colonization and continued colonialism, including residential schools. Similarly, a lack of transportation as a factor contributing to social isolation and Indigenous elders’ lack of ability to participate in community gatherings is a common theme in the literature64-67. While the need for Indigenous elders to be able to gather with peers and with children and youth to maintain and reintegrate culture and tradition in community has been noted60,68-70, the need for physical places for Indigenous elders to gather has not been directly spoken to. Thus, we recommend that future program design consider not just mental health support and transportation for First Nations elders, but also the need for sustainable places and spaces where work can physically take place.

Limitations

The program development and evaluation of the CRW role and program took place in four specific Northwestern Ontario First Nations communities and therefore findings will not be directly transferrable to other rural, remote, or Indigenous contexts. However, given some of the similarities that other Indigenous communities globally face, we believe the project and program may provide useful guidance to other rural and remote Indigenous communities interested in developing community-based programs generally and rehabilitative services specifically. In addition, while the CRWs going through the training program may provide services to other than community elders upon graduation, the main focus of the project was how well the program and role would address the health and wellbeing of elders with rehabilitation needs. The findings specific to older Indigenous people may be less relevant to people who are not older.

The project took place during a time when significant COVID pandemic restrictions were in place. This delayed research in some communities and limited the face-to-face research possible with community members living with vulnerabilities. Findings may have been slightly different if this had not been the case.

Conclusion

The goals of this project were to iteratively develop, evaluate, and adapt a CRW program training curriculum, and develop program and policy recommendations regarding the CRW role in alignment with community values and needs. Findings from this study highlighted that health care programs generally, and rehabilitative service programs specifically, are needed to provide holistic, appropriate, acceptable, and culturally safe care in Indigenous communities. It is critical that these essential programs, as well as other rural and remote programs, are developed in partnership with the local rural, remote and Indigenous communities, and incorporate local languages, cultures, and contexts. The four First Nations in this project also highlighted that elders lacked access to transportation, places to gather within communities, and mental health supports specific to elders. These findings should also be considered when designing community-based programs in rural and remote communities.

To address these findings, the curriculum for the CRW program was adapted: an Elder who speaks a local language will co-teach the modules, key physiology and rehabilitation words that are part of the curriculum have been translated into OjiCree and Ojibway, and rehabilitation dictionaries in Ojicree and Ojibway will be developed. A half-day of each module specifically discusses language and culture needs, and resources and assignments allow students to engage in traditional and community activities with First Nations Elders.

The health and wellbeing of the ageing population within First Nations in Canada, as well as Indigenous communities internationally, must be understood holistically. As noted by Hajban, et al29 a wide lens should capture the context within which rehabilitation needs exist and necessitates consideration of interrelated factors that may support the maintenance and improvement of not only mobility, but also quality of life, health, and wellbeing among First Nations and other Indigenous elders. To support the overall quality of life of First Nations elders, the team has submitted a policy brief to the Canadian Frailty Network, federal and provincial governments, recommending dedicated funding to address existing discrepancies in rehabilitation resources available to elders in Northwestern Ontario urban communities and First Nations.

In March 2022, a Northwestern Ontario college welcomed the first cohort of students to the CRW program. It is hoped that this program is sustainably delivered to subsequent cohorts of students in Treaties 3, 5 and 9, and Robinson-Superior and other rural and remote communities, both nationally and internationally, in need of such services.

Acknowledgements

This work has only been possible to complete with the guidance, support, and involvement of many people and many organizations. Therefore the project team would like to acknowledge and extend our heartfelt gratitude for the guidance and support from the advisory committee; from the Home and Community Care coordinators Nancy Keeskitay, Nancy Fiddler, Maria Spade and Martina Mckoop; without their assistance, the evaluation research could not have been conducted. The evaluation team also wants to thank everyone who, through their participation in the surveys and interviews, helped us develop and fine-tune the CRW program. The team also acknowledges the support that MHSc and MPH graduate students have provided in drafting parts of this article, editing and formatting it. This includes Hannah Melchiore in particular, but also Michelle McCormick and Alexis Harvey. Last but not least, our appreciation goes to the funders who made both the program development and evaluation possible: The Canadian Frailty Network, Indigenous Services Canada – Home and Community Care – Ontario Branch.

Sources of funding

This project was made possible with financial support from The Canadian Frailty Network and Indigenous Services Canada – Home and Community Care – Ontario Branch.