Introduction

The 2019 High-level Meeting on Universal Health Coverage of the United Nations General Assembly reaffirmed the commitment of its member states to cover all people with essential health services by 2030, ensuring quality health services are received by everyone, when and where needed, without incurring financial hardship1. These ambitious goals, however, have not been met by most countries in the Americas. The 2021 Global Monitoring Report on Universal Health Coverage (UHC) estimated that while the overall index of essential coverage was 77% in 2019, the Americas recorded one of the lowest absolute gains between 2000 and 2019, highlighting the importance to scale up efforts to reduce inequalities in access2.

Challenges to universal access to health are especially severe in rural and remote areas of the Americas. With about 20% of the population living in rural areas3, access to health services remains relatively low for these people. Some suggest this may be due to social and geographic inequalities in the supply of infrastructure, human resources for health (HRH) and medicines and other health technologies, despite regional expansion of UHC4. Compared to their urban counterparts, rural residents face different obstacles influenced by a unique combination of socioeconomic, political and cultural factors that exacerbate disparities in care-seeking behavior and the delivery of care not found in urban areas5.

The 2018 Delhi Declaration ‘Healthcare for All Rural People’ calls for people living in rural and isolated parts of the world to be given special priority if the goals of UHC are to be achieved. The Delhi Declaration places emphasis on primary health care (PHC) in rural areas and identifies rural proofing of policies that affect the health of rural people as a key priority6. Rural proofing is a systematic approach to accounting for rural factors in policy and strategic planning and, as such, benefits from an understanding of the characteristics of rural areas that could have an impact on how policies will be implemented and how people will access those services7-9.

As part of a dedicated Special Edition on Rural Proofing, the objective of this article is to provide a comprehensive understanding of the wide range of access barriers faced by rural and remote communities and to explore how barrier assessments can constitute part of a rural proofing approach. Using Guyana and Peru as case studies, this article aims to provide insight that is useful for rural proofing of policies, identifying specific adjustments that health policies need to make to overcome the barriers to accessing services in rural areas, and enabling improved UHC outcomes. A regional picture of such evidence is timely as Member States of the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) have recently recognized that an equitable path to UHC requires an understanding and addressing of the full range of factors acting as demand-side and supply-side barriers10.

Methods

Framework of analysis

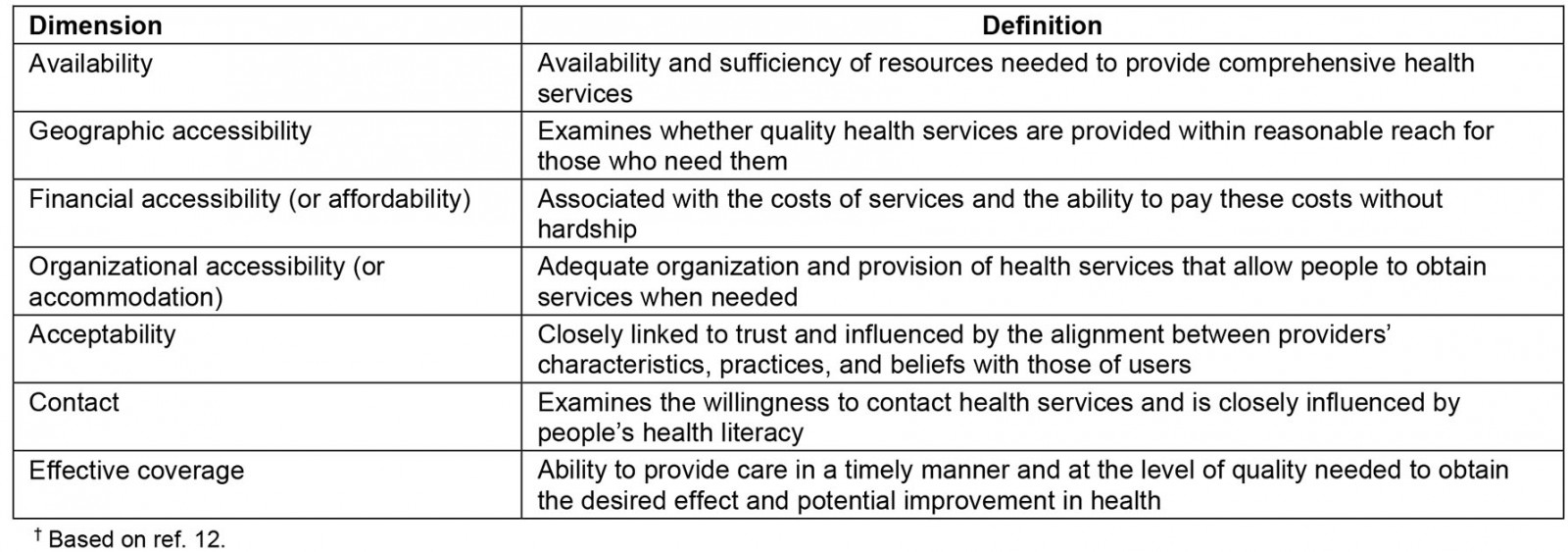

To operationalize accessibility, this study adopted the Tanahashi model of health services coverage11, which has been recently used to understand aspects of equity in access in the Americas and globally12. The framework defines five distinct dimensions of access: availability, accessibility, acceptability, contact and effective coverage of health services (Table 1).

Table 1: Dimensions of access based on the Tanahashi model of health services coverage12†

Study setting

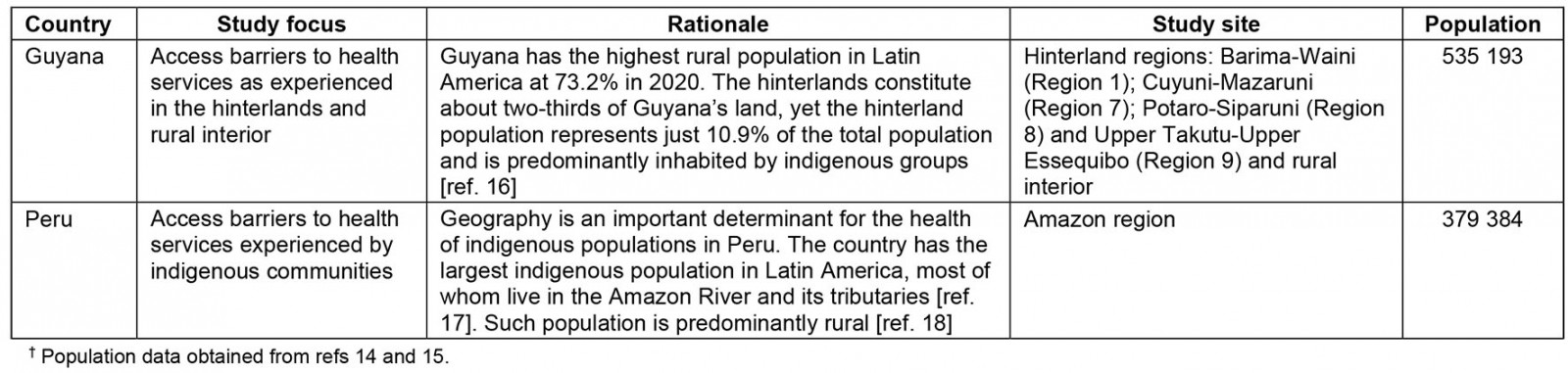

This article draws from a larger study exploring access barriers to health services in Guyana and Peru, which sought to improve health outcomes through strengthening sustainable health systems and reducing health inequities13, and which noted the role of barriers in reduced access to health interventions. Each country had sufficient data, including nationally standardized surveys and literature on health services access, as well as national policies in place for providing free, essential health services. The study sites in both countries were purposively selected to represent rural and hard-to-reach areas that face significant health challenges, and to illustrate the contrasting reality seen in the Americas: countries with high rural population (such as Guyana), and highly urbanized countries with hard-to-reach areas (such as the Amazon region of Peru) (Table 2). These examples illustrate how rural and remote populations are disadvantaged, even in countries where they may represent a majority, because health services tend to be concentrated in capital cities.

Table 2: Description of study sites14-18†

Research design

This study applied a concurrent triangulation design to collect and analyze data obtained from structured literature reviews, secondary analyses of existing household data, and interviews with health authorities. Quantitative and qualitative data were collected separately, and the results were interpreted together19. The approach sought to corroborate and cross-validate findings looking for convergence between the separate data analyses. The protocol was adapted for each site, as needed, retaining the same tools and methods.

Review of literature

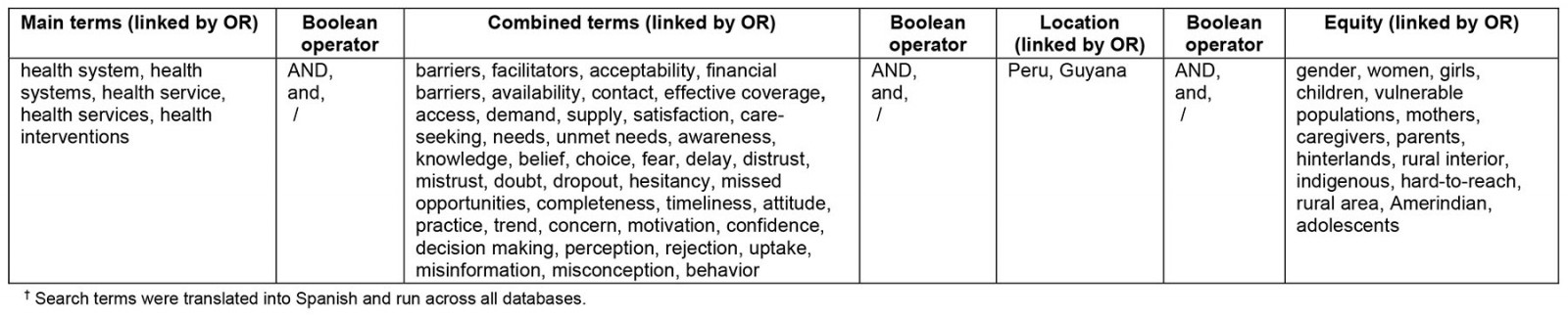

A narrative-style literature review was conducted to synthesize quantitative, qualitative, and mixed studies in English and Spanish, published between January 2009 and December 2021, to identify barriers to access health services in the two countries. The outcomes included the use and access to essential health services in the rural interior or hinterlands (Guyana) and in indigenous communities (Peru). Search terms were entered into the PubMed, Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO), and Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature (LILCAS) databases, including key words developed for the search strategy (Table 3). Contact with health authorities and a hand search of gray literature were also carried out.

Abstracts and titles were evaluated by two independent reviewers. Articles were excluded because they failed to satisfy one or more of the selection criteria: not in English or Spanish; did not focus on the target countries; did not report the methodology used; did not collect primary data; did not report on target populations (hinterland and rural interior populations in Guyana and indigenous communities in Peru); did not assess access barriers from the perspective of users or providers. Editorials, letters, and commentaries were excluded. The full text of the selected articles was retrieved and reviewed for inclusion by two reviewers. Any inconsistencies were discussed and resolved, and inclusion determined by joint consensus. Articles were removed if they were off-topic, methodologically inappropriate or could not be accessed despite attempts to contact the primary author.

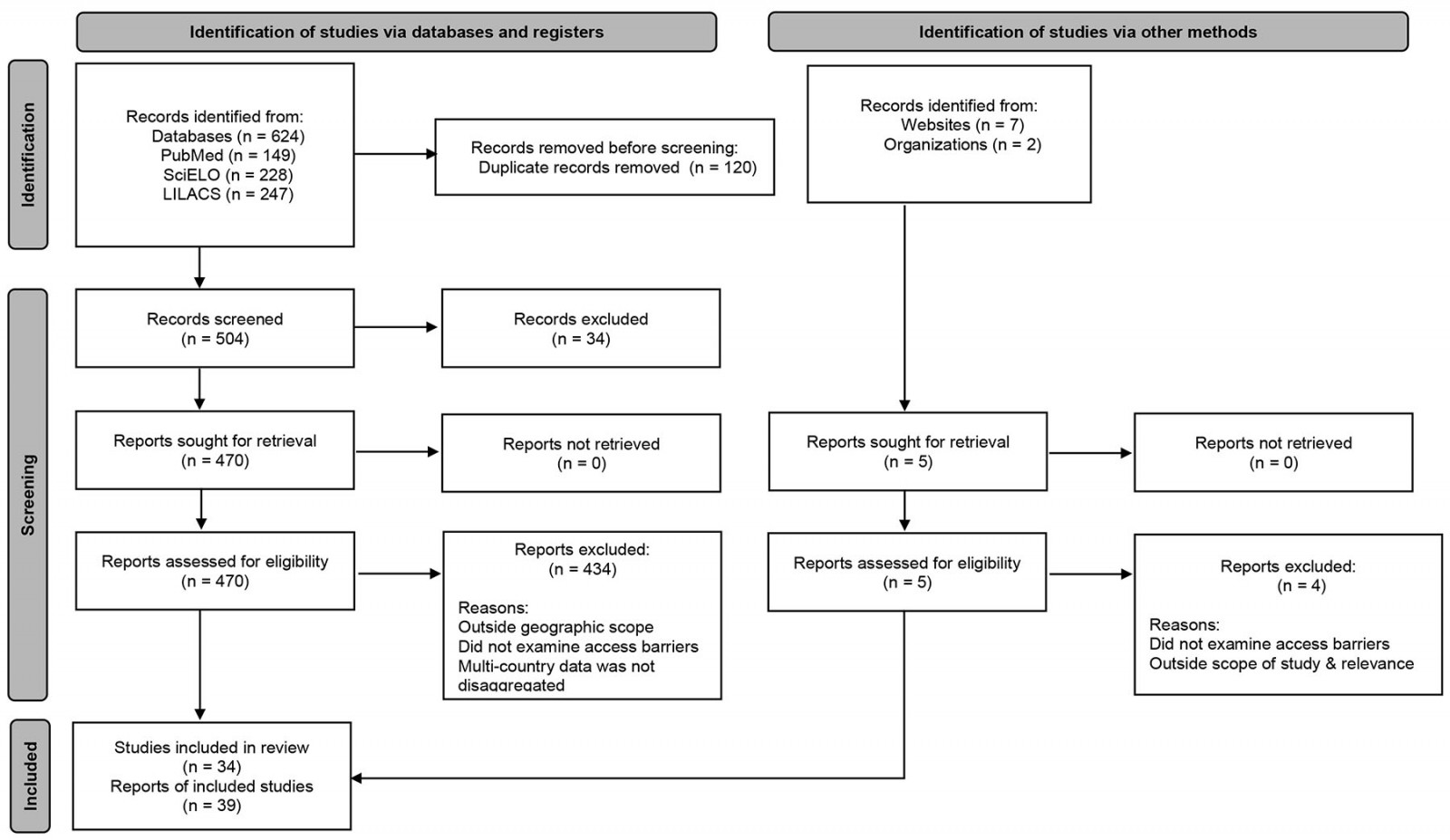

The decision regarding which studies would be selected was made using a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram (Fig1)20. Thirty-nine articles were analyzed in full (23 from Guyana and 15 from Peru). Each article was coded line-by-line, and the emerging trends were grouped according to the dimensions of access, clustering likes with likes and creating new codes when required. Matrices and frequencies were developed in Excel to summarize the findings based on emerging themes across the five dimensions of access. This allowed for an easier comparison and triangulation with the other results.

Table 3: Search terms for database searches of literature†

Figure 1: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart for search strategy of peer-reviewed and grey literature

Figure 1: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart for search strategy of peer-reviewed and grey literature

Quantitative component

Cross-sectional analyses of data retrieved from publicly available, nationally representative household surveys were carried out in the two countries, using the women’s questionnaire of the 2009 Guyana Demographic Health Survey (GDHS) and the 2003–2021 editions of Peru’s Encuesta Nacional de Hogares (ENAHO).

ENAHO’s data measured unmet need through foregone care expressed as the share of individuals who had a healthcare need but did not consult an ‘appropriate’ provider, or did not consult at all, and reasons for foregone appropriate care related to each of the five dimensions of access as previously described21. Study variables were determined by asking individuals about perceived health needs and related behavior in the 3–12 months prior to the survey (ie whether the individual had sought appropriate health services and reasons behind their decision). Appropriate care was defined in ENAHO as ‘situations when individuals sought care from any qualified medical professional in government health facilities and private hospitals/clinics during illnesses or accident’14. Other types of care such as ‘direct purchase of medications at pharmacies’ and ‘home remedies’ were defined as ‘inappropriate care’14.

The study also included multiple-choice response options to assess women’s views on the following GDHS question:

Many different factors can prevent women from getting medical advice or treatment for themselves. When you are sick and want to get medical advice or treatment, is each of the following a big problem or not? Getting permission to go? Getting money needed for treatment? The distance to the health facility? Having to take transport? Not wanting to go alone? Concern that there may not be a female health provider? Concern that there may not be any health provider? Concern that there may be no drugs available? Possible answers: Big problem / Not a big problem.

All variables were calculated according to the methodological recommendations of the Demographic Health Survey Program22.

Descriptive statistics were computed to describe access indicators relating to the dimensions of access using STATA v15.1 for Windows (StataCorp; http://www.stata.com), as described previously21.

Qualitative component

Key informant interviews were conducted in both countries to validate the findings obtained from the secondary data analyses and to identify context-specific solutions that would be practicable and reflect their needs and capabilities. In the case of Guyana, a total of nine key informant interviews were conducted, five with regional health officers and senior health visitors from the hinterlands and four with health officials from the Ministry of Public Health, in September 2021. In Peru, a total of 11 interviews were conducted with health officials from the regional health directorate of the Amazon region (DIRESA Amazona) between October and November 2021. A separate instrument was developed for each case and contained open- and closed-ended questions designed to elicit a deeper understanding of access barriers and to identify potential steps for confronting those challenges. Each instrument was slightly adapted based on the country’s study focus, as reported in Table 2. In Peru, items on study population were modified to obtain information about indigenous communities in the Amazon region, whereas in Guyana the questions were adapted to elicit information on hinterland and the rural interior populations. Questions on access barriers remained the same. Interviews were recorded, transcribed, and coded by two members of the research team (NH and RC) using NVivo v1.0 (QSR International; http://www.qrsinternational.com).

Data analysis

Synthesis of quantitative and qualitative data was conducted using thematic analysis to group access barriers according to the five dimensions of access and was described in a narrative form, highlighting points of complementarity and contradiction between the qualitative and quantitative data that could support the findings and reveal knowledge gaps. In the final stage, the thematic constructs were synthesized into analytical themes articulating the overarching dimensions of access. Triangulation was used to provide comprehensive results and/or validate and confirm results. Consistency among multiple data sources ensured the internal validity of the findings and increased the richness of the analysis. In other instances, triangulation was used to compensate for the lack of quantitative data on the target population and study foci. Interpretation of the relevance of the findings was achieved by consensus of the entire analysis team with backgrounds in mixed-methods research and intercultural health, in collaboration with health authorities.

Ethics approval

The study protocols were reviewed by the PAHO Ethics Review Committee, which concluded the proposals were not human subject research. All data on access barriers were obtained from secondary data sources. All quantitative analyses relied on publicly available, anonymized datasets. Additional permission was obtained for the collection and analysis of qualitative data. In Guyana, permission was sought and granted by the national and regional health authorities. In Peru, the protocol was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the San Fernando School of Medicine at National University of San Marcos (study code: 0186). Informed consent was obtained from each participant prior to interview.

Results

Evidence on access barriers

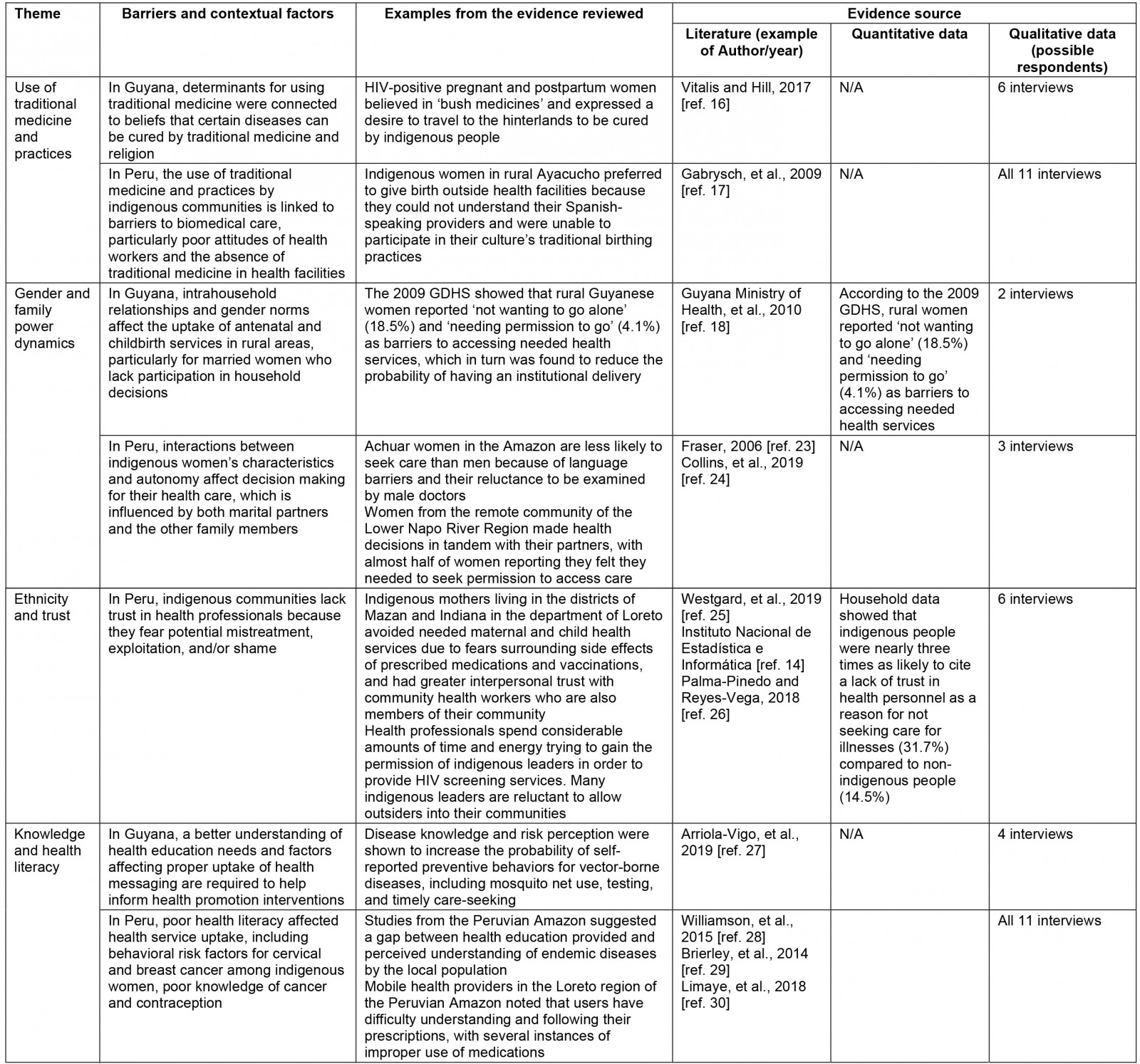

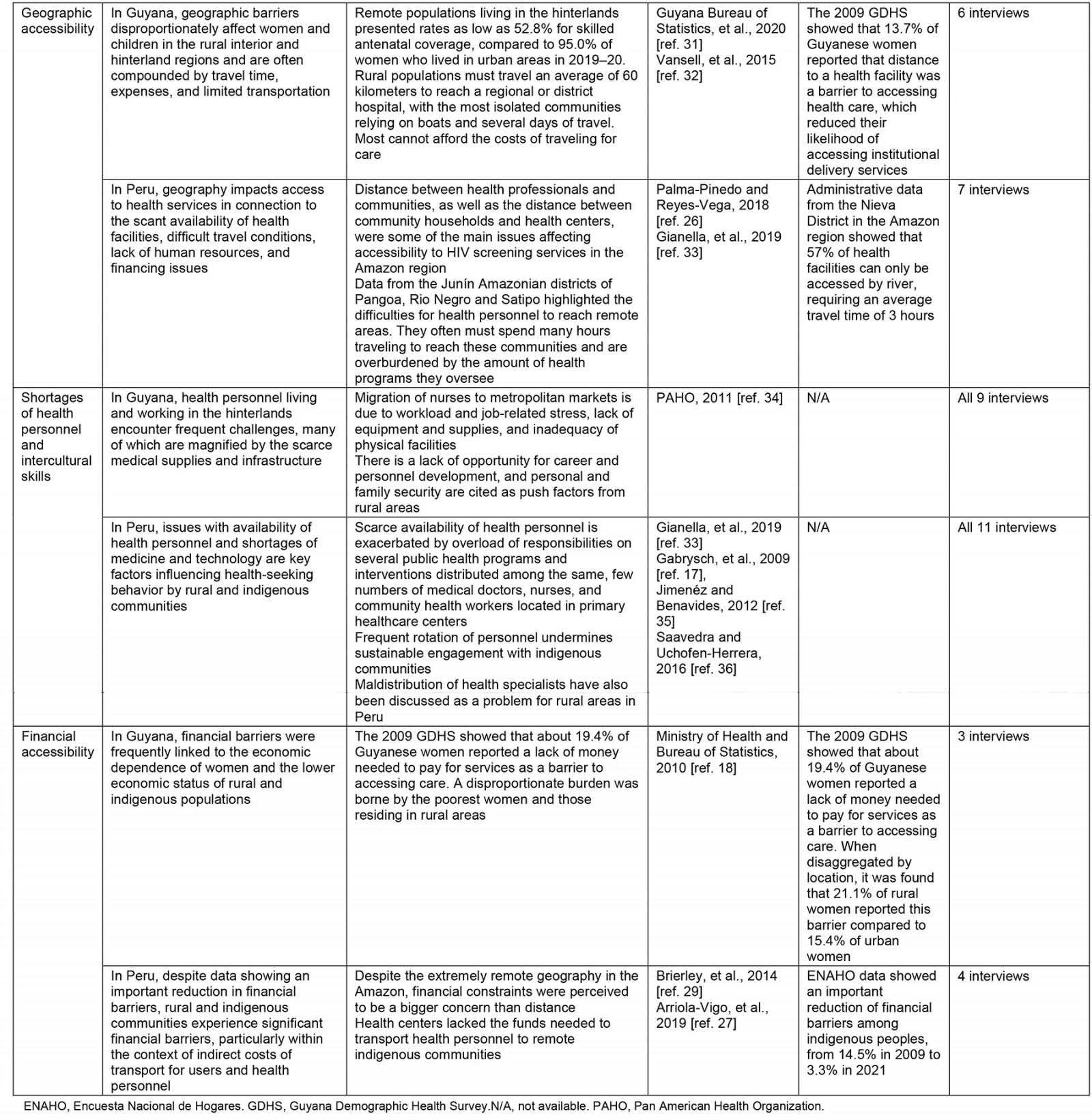

The synthesis of findings resulted in seven dominant emerging themes that cut across the qualitative and quantitative data. Results are presented in Table 4 and have been summarized below.

Table 4: Emerging themes identified through data analysis14,16-18,23-36

Use of traditional medicine and practice: Traditional medicine was found to be an important predictor of treatment-seeking in Guyana and Peru, particularly in rural communities inhabited by indigenous peoples. Various factors affected the practice of traditional medicine, with ethnicity, religion, and cultural beliefs about the superiority of traditional medicines as the factors most frequently reported in the qualitative and quantitative data. When discussing the study findings, health officials often recognized challenges to the incorporation of local indigenous practices into care protocols and explained that they were mainly due to shortages of health personnel with the necessary intercultural skills and the need for stronger multidisciplinary and intersectoral work.

Gender and family power dynamics: The integrated analysis suggests that health decisions are influenced by a range of power dynamics in rural communities. In Guyana, intrahousehold relationships and gender norms emerged as barriers to utilization of antenatal and childbirth services in rural areas, especially for married women who do not participate in household decision making. Literature from Peru also explored the interactions between indigenous women’s characteristics and autonomy in relation to different patterns of decision making. Lower level of education in women was often associated with a significant unmet need for health education about behavioral risk factors and adherence to preventive measures (discussed further below).

Ethnicity and trust: Ethnicity and trust were found to be interrelated predictors of care seeking in rural communities, particularly in Peru. The evidence from that country largely indicated that indigenous communities do not always trust health professionals because they fear potential mistreatment and/or shame. Community members were found to frequently avoid seeking care due to the shame and stigma associated with disclosure of health issues.

Knowledge and health literacy: Knowledge and health literacy impact the ability of individuals to understand health information and instructions from health providers, thereby enabling health service uptake and treatment adherence. Data from both study countries illustrated these issues and highlighted health literacy as an influential determinant of care seeking for services in rural and remote areas. Poor health literacy was particularly concerning in rural areas where lower educational levels and higher incidence of poverty often impacted residents.

Geographic accessibility: All sources of information analyzed from Guyana and Peru largely emphasized geographic accessibility as an important determinant of access. Rural and remote communities were more likely to have to travel long distances, often in difficult travel conditions, to the nearest health facility, making geographic location an important deterrent of health service uptake.

Shortages of health personnel and intercultural skills: Availability and training of health personnel was a challenge affecting rural and remote communities in both study countries. The impact of migration on availability of health personnel and access was an issue particularly highlighted in Guyana. Maldistribution of health personnel was also linked to long waiting times, limited operating hours, and dissatisfaction experienced by rural communities in both countries.

Financial accessibility: Although health services are offered free of charge through the public system in both study countries, affordability of the direct and indirect costs of care emerged as an important determinant of access in rural areas. Financial constraints were also experienced by health personnel, who often must use their own resources to cover the costs of transportation for community outreach activities, especially in the Amazon region of Peru.

Policy recommendations

Policy recommendations identified by the literature and health officials in Guyana and Peru largely emphasized the need for strengthening a PHC approach to improve access to services in rural and remote areas. Recommendations offered for Guyana centered on the country’s commitment to expanding integrated and first level of care services locally, including through the definition and implementation of a health services package and review and evaluation of existing public health legislation to strengthen institutional capacities at local levels. Health officials stressed the importance of fostering open dialogue with a diverse range of voices, especially with leaders and members of the hinterland communities, for the successful implementation of these changes. In Peru, policy recommendations were largely shaped by the study’s focus on indigenous health, which highlighted the need to improve local availability of financial and human resources to foster the intercultural adaptation of health services, in addition to the adoption of a holistic and intercultural approach to health promotion and disease prevention at the community level. In both countries, health officials highlighted the need to strengthen multidisciplinary and intersectoral collaboration simultaneously while fostering the inclusion and empowerment of the rural and indigenous communities. A priority shared by both countries was the need to improve the availability of HRH with PHC competencies. Both countries also discussed the role of health technologies, communications, and transportation infrastructure as key investment priorities for improving access in rural and remote areas. Likewise, they suggested the expansion and scale-up of community-based programs to overcome the cultural barriers associated with many services.

Discussion

Main barriers faced by rural and indigenous communities as identified by the study

The results of this study highlight a few critical issues that merit discussion given the similar challenges rural communities face worldwide. First, findings from both countries indicate that rural communities experience limited availability of HRH, compounded by inadequate infrastructure, equipment, medicines, and other supply-side barriers, as demonstrated in previous studies37,38. In the case of Peru, however, the lack of HRH was also tied to the sociocultural differences between rural indigenous community members and a mostly non-indigenous health workforce. Similar issues affecting the delivery of care in rural areas have been well documented in low- and high-income countries, and the lack of HRH in remote and rural health facilities is recognized as a problem globally39-41. Second, despite increased decentralization of service provision, insufficient transport, distance and transport costs still matter to rural communities in Guyana and Peru. Findings from several other studies on settings with free PHC have also highlighted that rural communities experience issues with costs and the fear of hidden costs, including for transport and medication42-45. Third, the evidence compiled here suggests that rural communities in both Guyana and Peru experience considerable non-financial barriers related to issues of acceptability (eg intercultural adaptation of health services, gender and autonomy, ethnicity and trust in health professionals, and knowledge and health literacy), as demonstrated elsewhere46-48. Importantly, this is one of the access dimensions given the least attention by both researchers and policymakers because it is often seen as difficult to measure and tackle49. Moreover, the findings suggest that the interaction between these barriers may be more important than the singular role played by each factor, thereby highlighting the complex, multifactorial nature of accessing services in rural settings. For example, in both countries, the use of traditional medicine was influenced by the geographic and financial barriers that limit rural people’s access to formal health services. At the same time, the use of traditional is also derived from a user’s sociocultural, religious, and spiritual values regarding health and illness. Thus, there is a need to recognize that rural communities are diverse in relation to race, ethnicity, and ways of life, which demand a holistic vision of rurality by researchers and policymakers alike37.

Lessons learned for rural proofing for health

The methodology applied to this study illustrates that barrier assessments in rural areas can potentially inform rural proofing. A major challenge to rural proofing is the lack of data from rural areas, which are needed to identify and address health inequalities and to signal country progress towards achieving health for all2,9. To compensate for the lack of data, this study systematically reviewed the existing literature and extracted data from national household surveys to gain a general understanding of the access conditions and barriers faced by people living in rural and remote areas of Guyana and Peru. Secondary data analysis was selected over primary data analysis because it required less time, financial, and human resources and was previously shown as a viable method for identifying and measuring access barriers12,21. The quantitative data and literature were assessed for validity against the experiences of rural health authorities in each country. Finally, the triangulation of literature, quantitative and qualitative evidence offered a systematic approach to developing a comprehensive understanding of the needs, circumstances, challenges, and opportunities in rural and remote areas. This was especially enriched by the qualitative information captured by the study.

Exemplars of rural proofing emphasize the need to understand and consider the health priorities and local contextual factors of rural areas prior to selecting or customizing an intervention50,51. To support contextualization of rural and remote areas, this methodology called for the involvement of rural and national health authorities who could speak to the current state of access in rural communities and provide potential recommendations for addressing the needs of rural health systems’ users. Collaboration across the health system governance continuum is thus an essential enabler for rural and remote community health service delivery50.

The study methodology has important implications for PHC-oriented research51. First, the use of evidence triangulation has offset the lack of disaggregated data on rural areas, allowing for a more holistic understanding of the health needs, challenges, and opportunities of rural and remote areas to be recognized as potentially informative for health systems, policies, and strategic planning. Next, the methodology promotes inclusion of rural stakeholders, including health authorities, whose knowledge on the local context can be harnessed to ensure that rural health needs are prioritized and addressed with culturally appropriate interventions. Moreover, the methodology is feasible enough to support regular collection of data and analysis on rural populations, particularly demand-side influences, which are emphasized in the operational and monitoring frameworks on PHC51,52. Finally, the methodology sought to support the analysis and transformation of data into knowledge, which is essential if policymakers are to identify and implement course-corrective actions to tackle gaps, bottlenecks, and improve health system performance52. To this end, the involvement of national and local health authorities in the design and implementation of the studies was an enabler for the identification of policy recommendations by health officials.

Policy implications for addressing access barriers in rural areas

While this study explored access barriers to general health services in two rural settings, the issues and policy recommendations identified could be considered for addressing access barriers faced by rural communities and ensuring that health systems are responsive to their needs and specific context.

First, health officials from both countries stressed that acceptability access barriers require more emphasis and adaptation on demand-side interventions. For example, participatory approaches and intersectoral action to empower indigenous communities and engage with community leaders may be critical for addressing cultural barriers which were found to prevent the timely uptake of health services in rural Guyana and Peru. To this end, community engagement and strong stewardship and governance structures that ensure effective collaboration between jurisdictional levels of health authorities, as well as social sectors, would be key enablers to service delivery adaptation in rural and remote areas50.

Another important aspect that could enable better access in rural settings would be improving working conditions of health workers while ensuring the availability of training opportunities on intercultural knowledge and interpersonal communication. Adopting an intercultural approach requires that health services not only respect indigenous and rural medical practices, but also promote and allow joint and complementary interactions between biomedical and indigenous approaches to prevent and treat health problems53.

Considering that geographic distance and long travel time to and from places of residence were noted as barriers for rural populations in both case studies, it appears that community-based services could play a crucial role in improving access to primary care actions38. In addition, telehealth technology, when used as an adjunct to community visits by fly/drive-in clinicians, has been recognized as a critical component for overcoming geographic barriers, including long travel time and distance50. It also has the potential to enable knowledge exchange, professional development, and clinical support for the rural health workforce, which could help alleviate some of the availability barriers described above50.

In both countries, the need for strengthening a PHC approach was emphasized. PHC interventions that take into account social adaptation and policy innovations have been widely advocated to cope with social and cultural barriers and enhance widespread adoption of technologies54. Some of these initiatives involve integrating community resources, for instance providers consulting community leaders or elders regarding cultural issues, participating in community events, and integrating additional community resources53. In other settings, the use of community-appreciated practices has helped to increase cultural acceptability of services by incorporating the use of natural healers and other adaptation strategies to the cultural style of patients53.

Modifying approaches to health provision and engaging communities requires enabling policy and prioritizing investments in PHC, with the support of the health and education system in general54. Furthermore, the political and technical viability of these initiatives will require strong national and local governing capacity and institutional structures oriented to the rural experience. This requires a whole-of-government and society-wide approach to improving essential public health capacities and health-system resilience in a post-pandemic context55. Capacity-building efforts for rural populations in Peru and Guyana could include improved regulation of critical health system resources, especially PHC-based human resources.

Finally, this study identified the need to increase the availability and distribution of HRH in rural settings, where high turnover of staff and a lack of incentives were widely recognized as drivers of HRH shortages. To improve access to HRH in rural areas, WHO’s global policy recommendations include interventions based on education, regulation, financial, and professional and personal support.

Strengths and limitations

Application of this methodology in two rural settings has resulted in greater awareness of its potential for rural proofing. First, it has been shown that mixed methods are not only feasible but also effective for conducting high-quality research on access barriers to generate solutions that are responsive to rural contexts. One facilitator for the feasibility of this study was the reliance on household surveys and literature, which reduced the amount of technical expertise needed to gain a general overview of access in each rural area and allowed emphasis to be placed on engagement with decision-makers. In turn, this helped to place the participation of rural stakeholders at the center of the research, as is urged by best practices on participatory action research56. Next, the methodology’s application to study access relevant to a particular setting such as the Amazon region (Peru) and hinterlands (Guyana) was a useful strategy for narrowing the literature search results without jeopardizing the comprehensiveness of the assessment. When speaking to rural health authorities, it was found that many of the barriers identified were applicable to the broader health system and service offerings in rural and remote communities.

This study is the first the authors know of that incorporates a triangulated approach to investigate access barriers in rural communities of Latin America and the Caribbean. The combined quantitative and qualitative evidence from this study provided information on a broad range of access barriers and highlights the multifaceted relationship between access barriers and just how critical it is to complement quantitative indicators with qualitative data to understand the reality of rural communities. This information could help guide the development and implementation of innovative approaches that can enhance provision of services in rural settings.

This was an exploratory study based on secondary data and input from health authorities living and working in rural areas. Although the methodology has provided a comprehensive understanding of access barriers, it remains a work in progress and should be strengthened further. Future studies should aim to engage rural community representatives and health service users throughout the research process. This means rural communities and their representatives should be active collaborators in the selection of research topics and questions, study design, data collection and analysis, and the dissemination of results56. Participatory action that effectively engages rural communities will promote community ownership of rural health research, as well as trust and partnership between rural people and local, regional, and national decision-makers56. The breadth of secondary data used in this study and the perspective of health officials, including on the challenges experienced during policy implementation, provided powerful insight about rural and remote communities. While setting-specific findings are invaluable for characterizing local access barriers and care-seeking patterns, they cannot be used to generalize to an entire region or country. Still, the strength of the study lies in its ability to pool results across sites to extract patterns that may apply across countries and cultural contexts, as well as key differences between different contexts.

There are inherent difficulties associated with locating qualitative studies due to their poor indexing. The search parameters, particularly restricting the language to Spanish and English, may have also prevented the identification of relevant articles. It is important to note the obvious contextual differences between Guyana and Peru, as well as within each country, including the characteristics of the study population in the studies identified during the literature review. Additionally, the use of quantitative data from an exclusively female sample may have limited the generalizability of the findings in Guyana. At the same time, the study had a focus on maternal and child health, which directly affects women and requires that their voices be heard by policymakers and other key decision-makers. Since women may not always have a strong voice in rural social and health research, the use of data solely from women may help emphasize the experiences of rural Guyanese women and could provide a balance to the normative male model in research. While the direct findings are not necessarily generalizable, theoretical insight arising from the synthesis of the included studies in both cases maybe transferable to inform rural proofing in other settings.

Conclusion

This study presented an approach for data collection and analysis that can be used in rural settings to identify and corroborate a broad spectrum of access barriers. It further proved the feasibility of using mixed-methods approaches to evaluate access barriers faced by rural communities as part of in-country studies. The findings indicate that both demand- and supply-side barriers create challenges for accessing services in rural areas of Guyana and the Peruvian Amazon. Several barriers found in these settings concur with the global literature, including issues of HRH availability, lack of transport, and acceptability issues. At the same time, barriers potentially more specific to these settings were found, including gender norms and roles, low health literacy, and lack of cultural adaptation. As indicated by this study, more efforts are needed to ensure that countries of the Americas can reduce inequalities and achieve universal access to health services. Innovative PHC approaches would be required to address these issues and to guarantee improvements in stewardship of rural health authorities and governance capacities, financial sustainability, expansion of first level of care, and increased numbers of skilled health personnel. Overall, this study indicates that barrier assessment methods, such as those applied in Guyana and Peru, can provide evidence that has potential value for rural proofing of policies, strategies, plans and programs, either ex-ante or post.

Statement of funding

This study was financed by the U.S. Government, through the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) under the PAHO–USAID Umbrella Grant Agreement 2016–2021. This article is also part of the WHO-sponsored Rural and Remote Health special edition ‘Rural Proofing of National Health Policies, Strategies, Plans and Programmes’, the funding for which was provided through the WHO–Government of Canada project ‘Strengthening Local and National Primary Health Care and Health Systems for the Recovery and Resilience of Countries in the Context of COVID-19’ (2021–2022).

Disclaimer

This article represents solely the views of the authors and in no way should be interpreted to represent the views of, or endorsement by, their affiliated institution(s), or of WHO as sponsor of this RRH special edition. WHO and PAHO shall in no way be responsible for the accuracy, veracity and completeness of the information provided through this article.