Introduction

Indigenous peoples of Canada – First Nations, Inuit, and Métis – experience ongoing health inequities due to colonialism that negatively impact various health factors and social determinants of health1,2. Oral health care is no exception. Oral disease is highly prevalent and severe among Indigenous populations within Canada3-5. Dental disease occurs much earlier compared to the general population – as evident by the prevalence and severity of early childhood caries (ECC)6,7. In 2013, an Indigenous child was 8.6 times more likely to undergo general anesthesia for the treatment of ECC compared to the general population in Canada6. The early onset, high prevalence, and severity of dental disease among Indigenous populations create a high demand for restorative oral health care7,8. However, dental disease is preventable and preventive oral health care is the ideal approach to reducing the prevalence of dental disease9.

In dental public health, there has been a rise in preventive-focused programs and studies for Indigenous populations8,10,11. Although many of these studies show reductions of dental disease and improvements based on current outcome goals at the community level, oral health disparities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples persist. Similar Indigenous–non-Indigenous health outcome disparities cut across other fields of health care2,3,5,6,11,12. This demonstrates an urgent need to evaluate oral healthcare delivery – particularly preventive care delivery – to gain insight on how to better serve Indigenous communities for happier and healthier smiles. The Truth and Reconciliation Call to Action #19 calls for the actions of ‘consult[ing] with [Indigenous] peoples, to establish measurable goals to identify, direct, and close the gaps in health outcomes for Indigenous peoples’13. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada was established to guide a process of truth and healing for the reconciliation of Canada with Indigenous peoples14 and released the 94 Calls to Action to guide actions of reconciliation in numerous areas, including health13,14. (Reconciliation was described as the act of establishing and maintaining a mutual respectful relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples, requiring awareness of the past, acknowledgement of the harm inflicted, atonement for the causes, and action to change behaviour14.) The Call to Action #19 is important to this study, as Indigenous peoples of Canada have historically been excluded from the planning and evaluation of their own health and are under-represented in quantitative health data2,15.

This study aimed to define ‘quality preventive oral health services’ in a First Nations, on-reserve community setting located in Northern Manitoba, Canada, to provide a framework of quality that reflects Indigenous perspectives and can be used in the planning and evaluation of preventive oral health services for Indigenous communities. To accomplish this, it was vital that the participants had direct involvement throughout all stages of the framework development, thus allowing for the control of data and information by the participants and their community16. For this reason, concept mapping methodology was selected.

The expectation was for the resulting framework to include Indigenous-specific considerations and contexts, which may be overlooked in other measures of dental satisfaction or quality of care. Furthermore, the decision to create a new framework and new measurement tool is not based on creating evidence of the existing gap in oral health services between Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations; rather, the goal is to evaluate the needs and processes of closing the existing gap in preventive oral health care.

This study is part of the Nistam Nipita (‘My First Teeth’ in Cree language) study, which aims to prevent and reduce tooth decay in young Indigenous children (Principal Investigator (PI) Dr Herenia P. Lawrence). This article describes the development of the conceptual framework which in turn was used to construct a measurement tool to evaluate the preventive oral health services for Indigenous communities17.

Methods

Population and setting

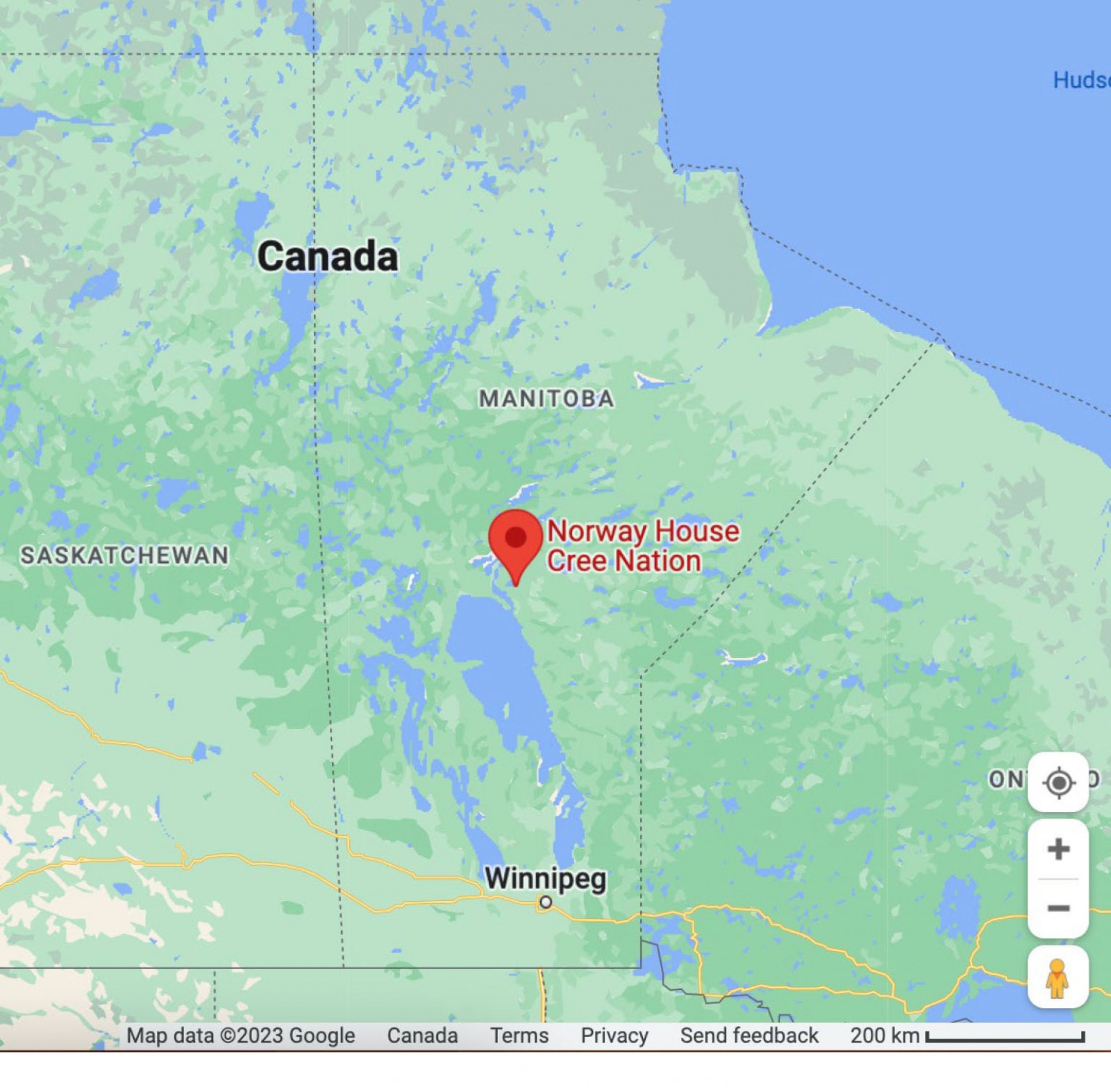

The study was conducted in partnership with the Norway House Cree Nation (NHCN). NHCN is a First Nations community on Treaty 5 land in Northern Manitoba, Canada18, shown in Figure 1. The NHCN has a live-in dentist who works at the dental clinic during weekdays and a dental therapist who works at the school dental clinic19. Difficult dental cases are referred to Winnipeg (807 km south of NHCN via the highway) or Thompson (294 km north of NHCN via the highway), both of which are accessible via highway or by flight19.

Figure 1: Map locating Norway House, Manitoba.

Figure 1: Map locating Norway House, Manitoba.

Community engagement

Prior to the study, the student PI (JBW, First Nation from the Squamish Nation) and the Nistam Nipita PI (HPL) met with community members and the NHCN Health Division in person to discuss the study goals and the proposed approach, ensuring that these reflected the needs and interests of the community. The student PI continued working in person for the entirety of the concept mapping processes.

Eligibility and recruitment

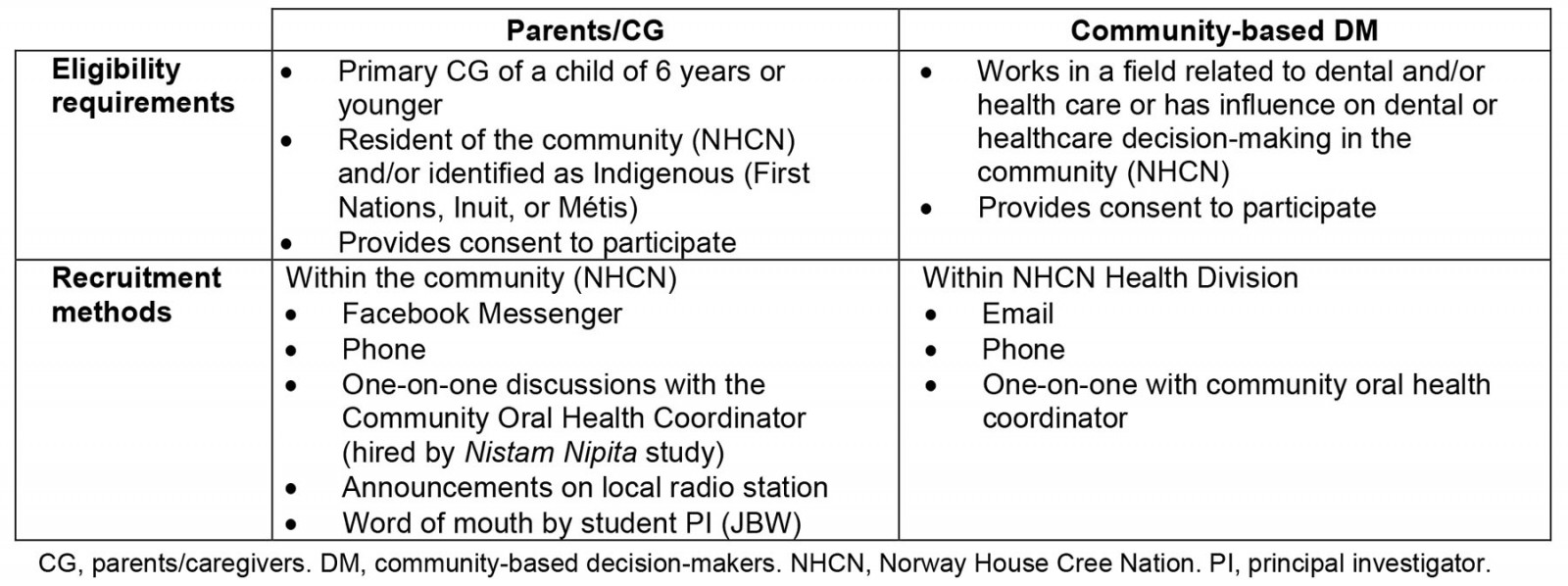

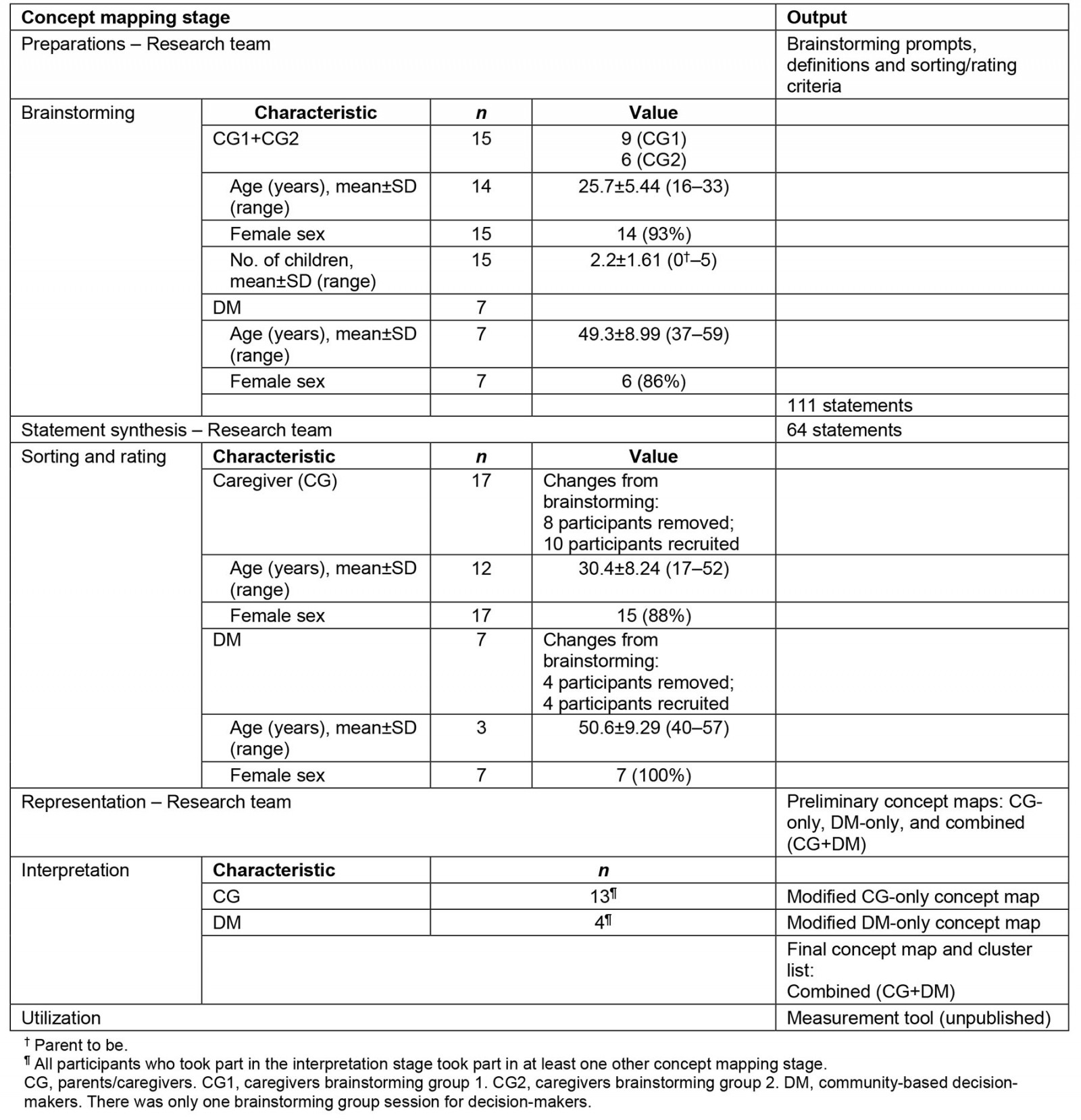

Participants fit into two groups (Table 1): community caregivers (CG) or community-based decision-makers (DM). The rationale for separate groups was that perceptions may differ between the groups, allowing for the exploration of ‘quality of service’ in its entirety; and that combining the groups may bring about unequal power dynamics, which may bias or limit data/statement collection.

Recruitment occurred with the help of a community oral health study coordinator, primarily through announcements on local radio, Facebook Messenger, and word of mouth (Table 1). Participants were invited to take part in any or all of the participant concept mapping tasks (brainstorming, sorting and rating, and interpretation sessions), but were not obliged to take part in all stages. For this reason, an informed consent process took place at each of the different stages. Participants received an honorarium to compensate them for their time, input, and to relieve travel or childcare costs for parents/caregivers to attend a session.

Table 1: Eligibility requirements and recruitment methods

Concept mapping

The concept mapping process follows five stages: brainstorming/idea generation, sorting and rating, representation, interpretation, and utilization of the conceptual domain20. All sorting/rating and mapping analysis was run through Concept System’s GlobalMax Concept Mapping Software v2017 (http://www.conceptsystemsglobal.com)21.

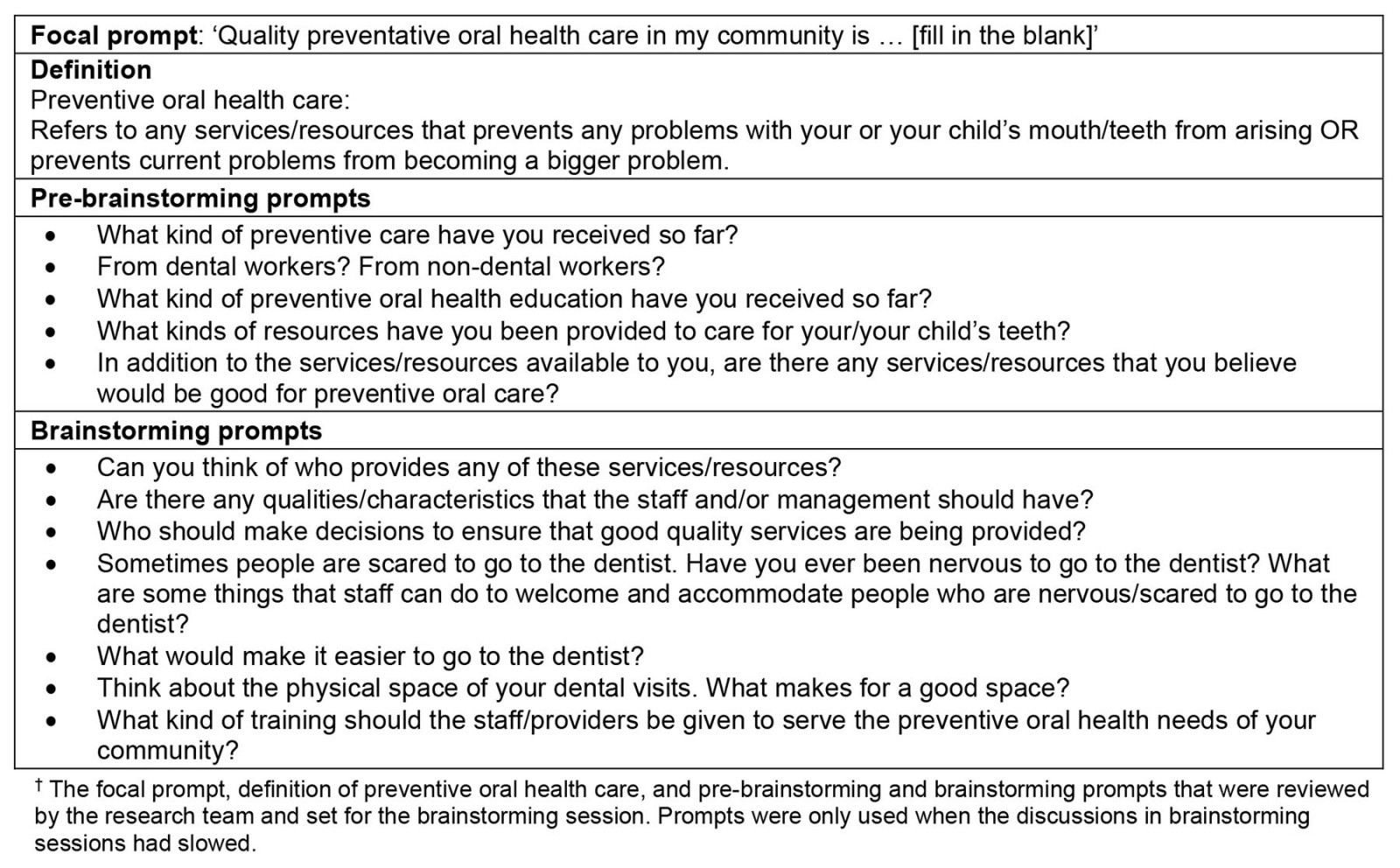

Preparations: To ensure that the conversations properly focused on the quality of preventive oral health care in Indigenous communities, the research team pre-tested a focal prompt, a set of pre-brainstorming prompts and definitions, a set of brainstorming prompts, and the rating criteria for the sorting and rating task (Tables 2,3).

Preventive oral health services were defined as those that had prevented problems with the mouth or teeth from occurring, or prevented current issues with the mouth or teeth from getting worse. This was to understand how to improve preventive care when the current status of oral health services is so heavily focused on restorative care.

Table 2: Brainstorming prompts and definitions†

Table 3: Rating questions and responses†

Brainstorming/idea generation:

Data collection Brainstorming sessions were held to generate ideas surrounding the quality of preventive oral health care in a First Nations community. The facilitator (JBW) led each session with the pre-brainstorming prompts and definitions (Table 2), followed by an introduction to the focal prompt ‘Quality preventive oral health in my community is …’. Ideas were generated through participants’ reflections and refining those statements to complete the focal prompt. Prompts were used if conversations veered from the main focus. Statements were recorded by the research team or by a paid recorder from the community.

At the end of each brainstorming session, the facilitator reviewed each statement with the group to ensure that it accurately reflected qualities of preventive oral health services and that it was worded in a way that captured the intended meaning. The facilitator brought an eagle feather – which had been gifted as a symbol of her journey of growing knowledge – to use as a talking stick. Talking sticks as an Indigenous methodology bring a philosophy of communication that reflects respect, resilience, reciprocity and responsibility into the conversation22. Using the talking stick, the sessions ended with reflections from each participant on a statement that stood out to them or on the brainstorming process itself.

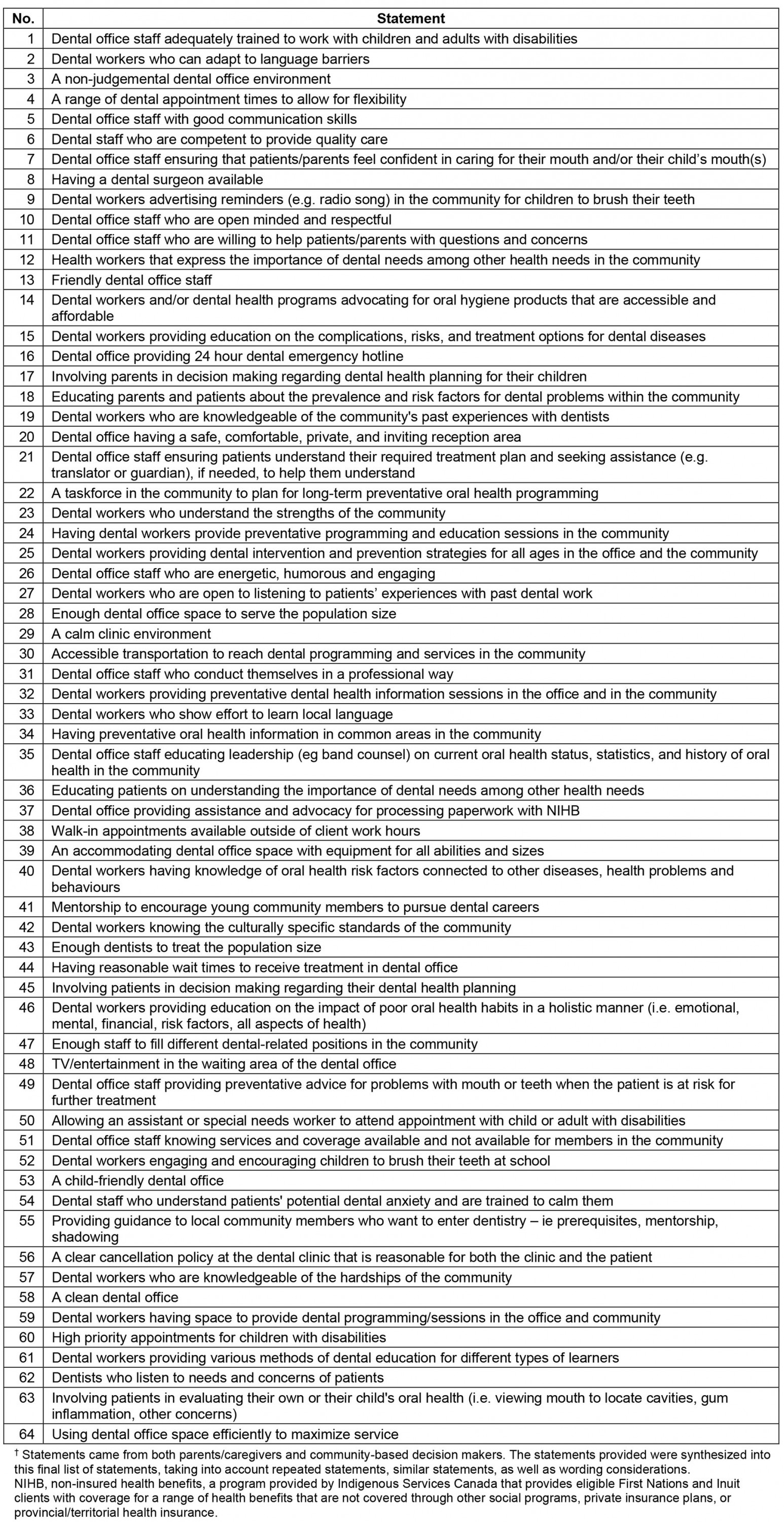

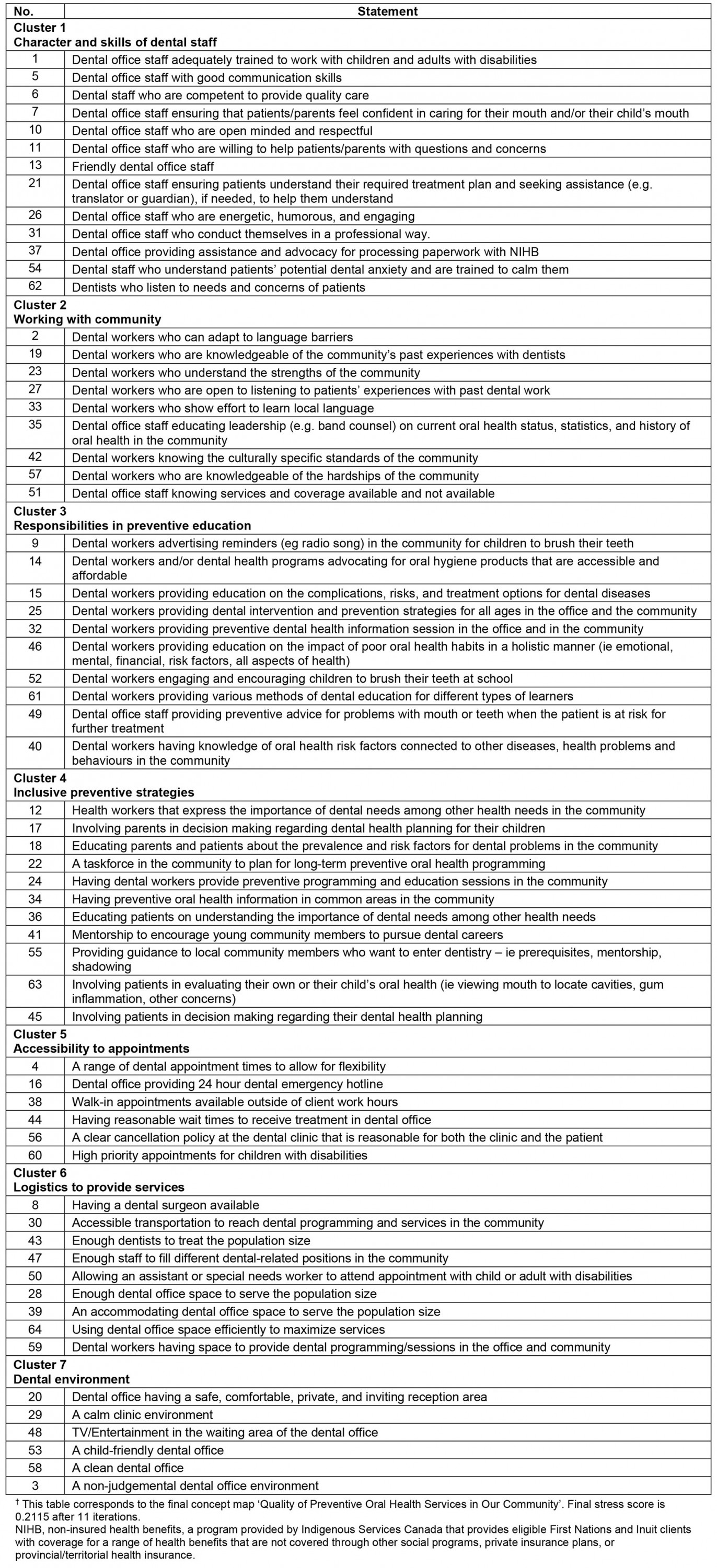

Data analysis Overall, 111 initial statements were generated in the brainstorming stage and were coded by brainstorming group (CG group 1, CG group 2, and the DM group). The research team reviewed and synthesized the statement lists multiple times – accounting for similar or identical statements, overly complex or overly simple statements, and statements that did not answer the focal prompt – to create one manageable set of statements. The research team also reviewed the statements to ensure that the wording was clear, understandable, and formatted to fit the focal statement. A final list of 64 numbered statements (Table 4) was carried forward to the sorting and rating stage.

Table 4: List of final 64 brainstorming statements†

Sorting and rating:

Data collection Participants were provided with the 64 numbered statements (Table 4) written on index cards and asked to sort the cards into piles in a way that ‘made sense to them’. The rules were: (1) each card must be sorted into a pile, (2) a card can only belong to one pile and (3) the pile must be named with the theme it represents. All sorted statement card decks were recorded and retrieved for quality assurance and data entry.

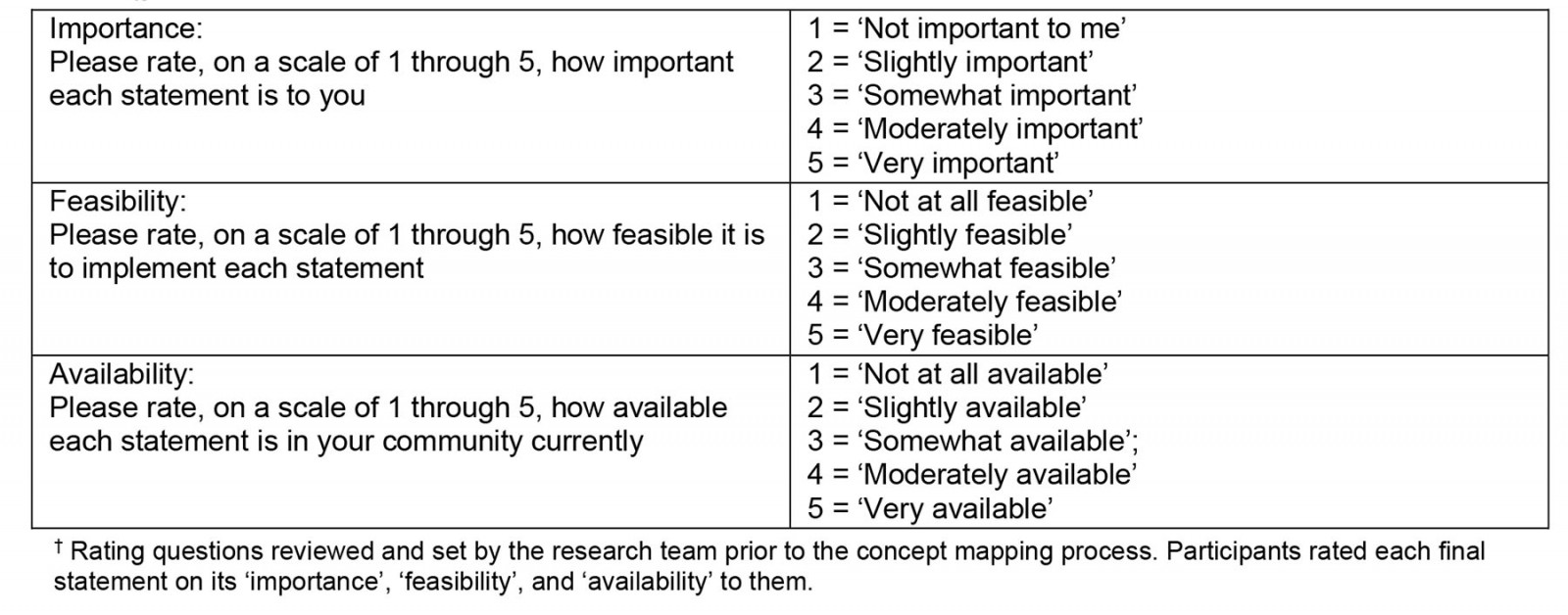

Participants were then asked to rate each statement on a five-point Likert-type scale based on importance, feasibility, and availability (Table 3). Importance rating criteria were set up to provide insight into the priorities of preventive oral health care for the community, whereas feasibility and availability rating criteria were created to inform the planning of preventive oral health care for NHCN.

Representation:

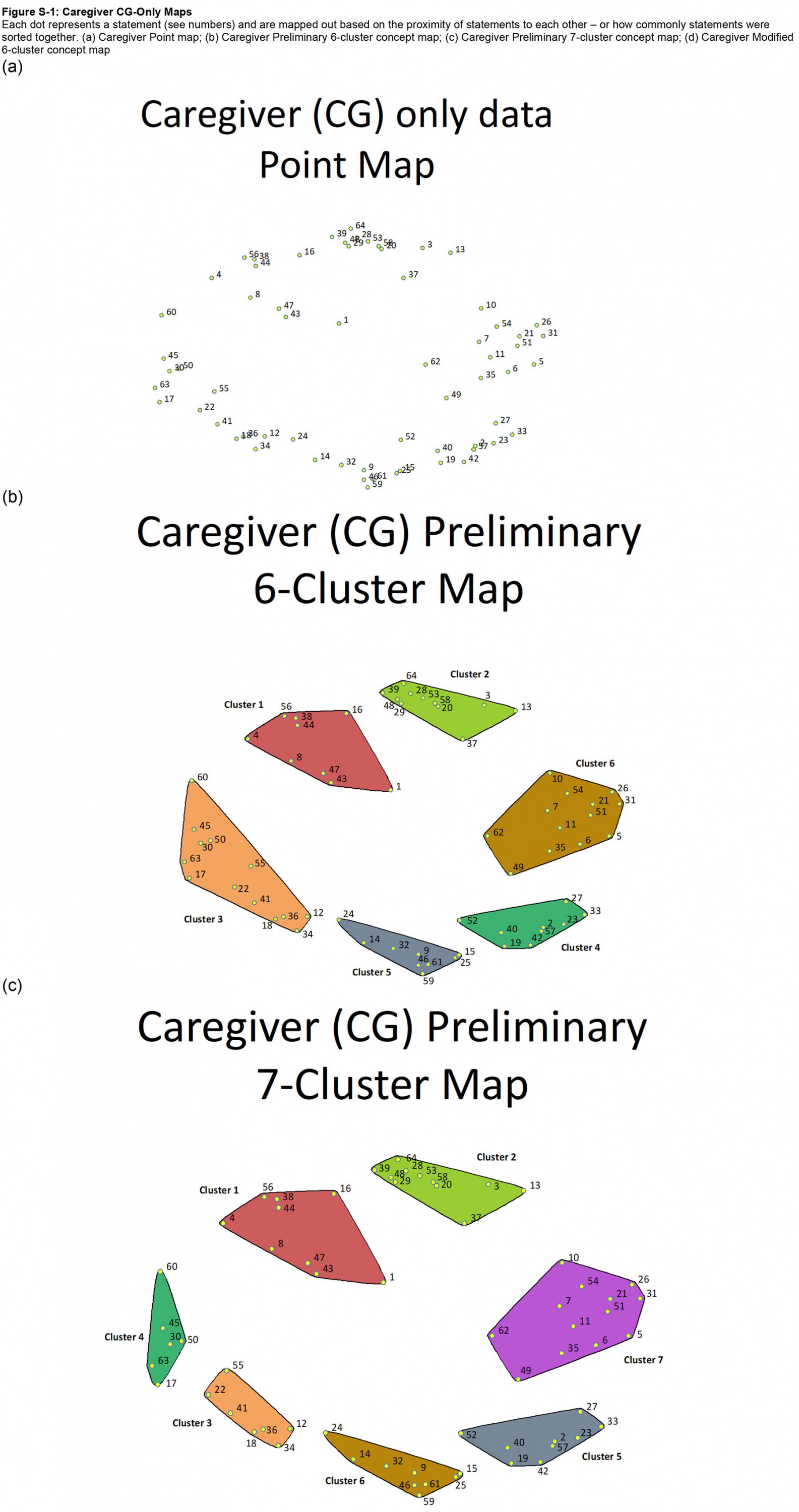

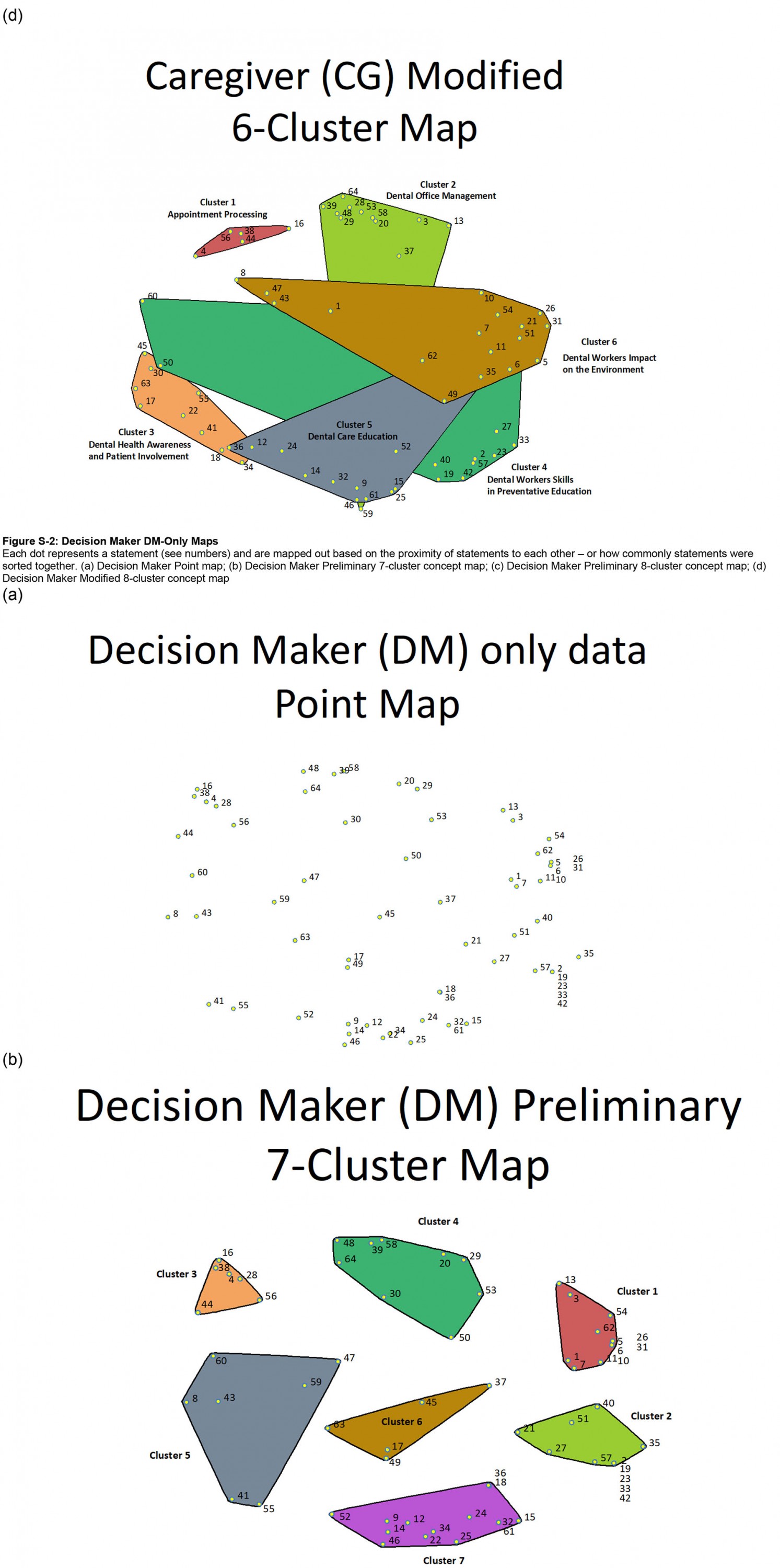

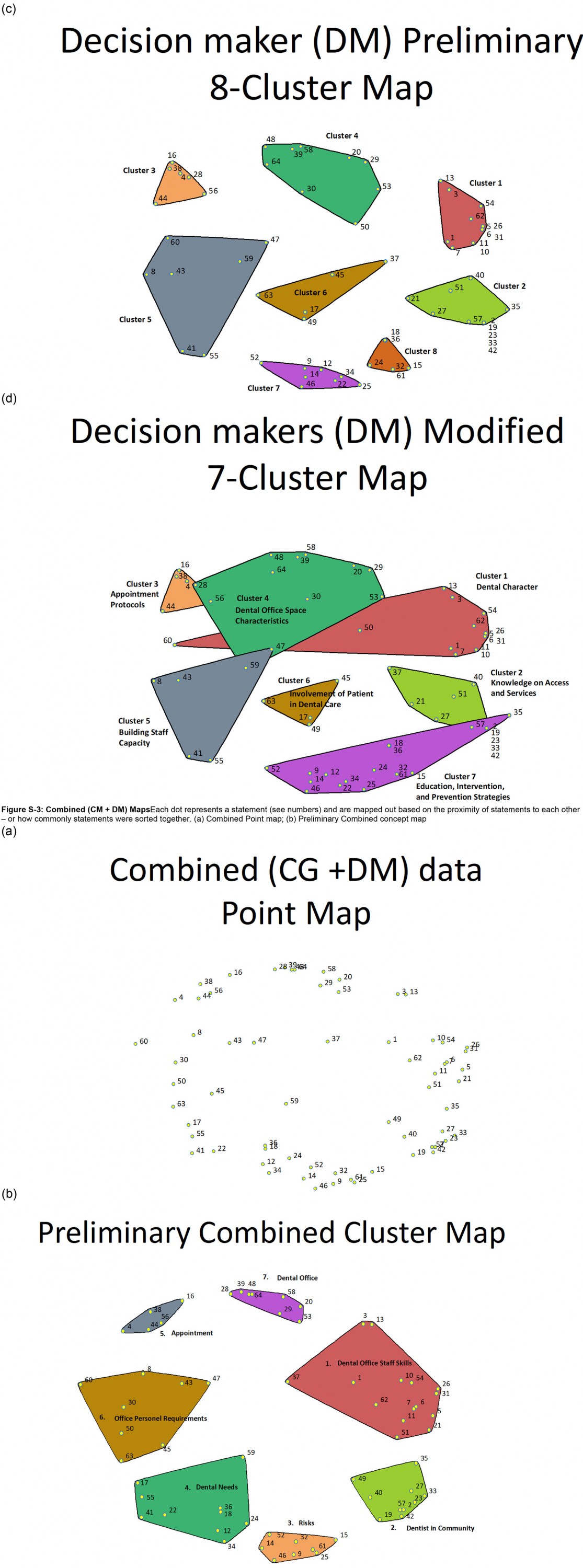

Data analysis A series of maps created through hierarchal cluster analysis and multidimensional scaling by GlobalMax provided visual representations of the sorting and rating data. Point maps and cluster maps were generated from CG data only, DM data only, and Combined CG and DM data.

On the maps, each point represents one of the 64 statements. There is no magnitude or direction along the x- or y-axis; the statements are dispersed based on the likeliness that items were sorted together. Thus, it is the proximity of the points, not the location, that is important. The cluster maps are identical to their respective point maps but are physically grouped into x number of clusters based on the similarity of statements. Multiple preliminary cluster maps were generated and reviewed so that two maps of best fit were selected for each group (CG only, DM only, and CG and DM combined) based on initial judgement of the similarity of items within each cluster and the distinction between items in other clusters. These preliminary cluster maps (Appendix I) were carried to the interpretation stage.

Stress test The GlobalMax software performed a stress test on the sorting data to assess the ‘badness of fit’ or the inverse of a correlation coefficient. The lower the score, the better the concept map represented the correlation of items. Ideal stress test values are less than 0.36, which indicates the participants easily understood the statements and were able to sort them20.

Interpretation:

Data collection Each group of participants (CG and DM) collectively reviewed their respective preliminary maps, looking at the groupings and items within each cluster. Each group decided on a map of best fit. Any modifications suggested were discussed and finalized as a group, after which the maps were finalized by labelling each cluster. Cluster labels were given through suggestions or modifications from the labels given in the sorting task, or through discussion between participants regarding the theme of the cluster.

Utilization of the conceptual domain The resulting concept maps and rating data informed the development of a measurement tool to assess the quality of preventive oral healthcare services in First Nations or Indigenous communities17.

Ethics approval

Community engagement occurred prior to the study’s commencement and received approval from the health director, oral health workers, program managers, and parents in the community. The study was approved by the University of Toronto Health Sciences Research Ethics Board (REB Protocol #37938) and the Norway House Cree Nation Chief and Council. The study and its design follow the guidelines provided by the Tri-Council Policy Statement (TCPS2 2018) on Research involving First Nation, Inuit, and Métis Peoples of Canada23, as well as the First Nations principles of ownership, control, access and possession24. Participants were provided with a consent form at the beginning of each session, which they signed after their questions about the study were answered.

Results

The sample

The sample size varies between each of the concept mapping stages. Some participants took part in one stage but were unable to take part in the next stage, and new participants were recruited at later stages. Overall, 22 participants completed brainstorming, 24 completed sorting, 24 participants completed importance ratings, 23 participants completed feasibility and availability ratings, and 17 participants completed the interpretation sessions. All participants were from the NHCN and took part in the concept mapping tasks in person at the NHCN Health Division in Norway House, Manitoba. At least 88% or more of the participants at each stage were female. Of the caregivers, parents had 1–5 children, averaging at 2.2–2.5 children per caregiver. See Table 5 for a breakdown of CG and DM participants at each stage.

Table 5: Study outline and participant characteristics

Developing the conceptual domain – brainstorming to interpretation

In total, 111 statements were generated from the brainstorming groups. Through seven rounds of statement synthesis, 28 items were identical and thus combined with another statement (total 83 statements), 20 items were similar and combined with another statement, 3 items were split due to double-barreled wording, and 2 items did not apply to the definition of preventive oral health services, thus producing a final list of 64 numbered statements. On average, 24 participants sorted the 64 index cards into 5.5 piles, a median of 5 piles, a maximum of 9 piles, and a minimum of 3 piles. The rating data held 23 completed rating datasets, with one participant completing the importance rating set, but not the feasibility or availability rating sets.

The research team created preliminary maps for both CG-only and DM-only groups – each consisting of six- to eight-cluster preliminary maps based on the judgement of the similarity of items within each cluster and the distinction between items in other clusters. The CG map had a stress score of 0.2293, the DM map 0.2556, and the combined (CG + DM) had a stress score of 0.2115 – showing low ‘badness of fit’, indicating that participants easily understood the statements and were able to sort them.

The CG-only group agreed on a six-cluster map as their map of best fit. Upon group discussions, 11 items were moved between clusters, providing the final CG cluster map. The DM-only group agreed on a seven-cluster map and moved six items between the clusters. These preliminary concept maps are shown in Appendix I.

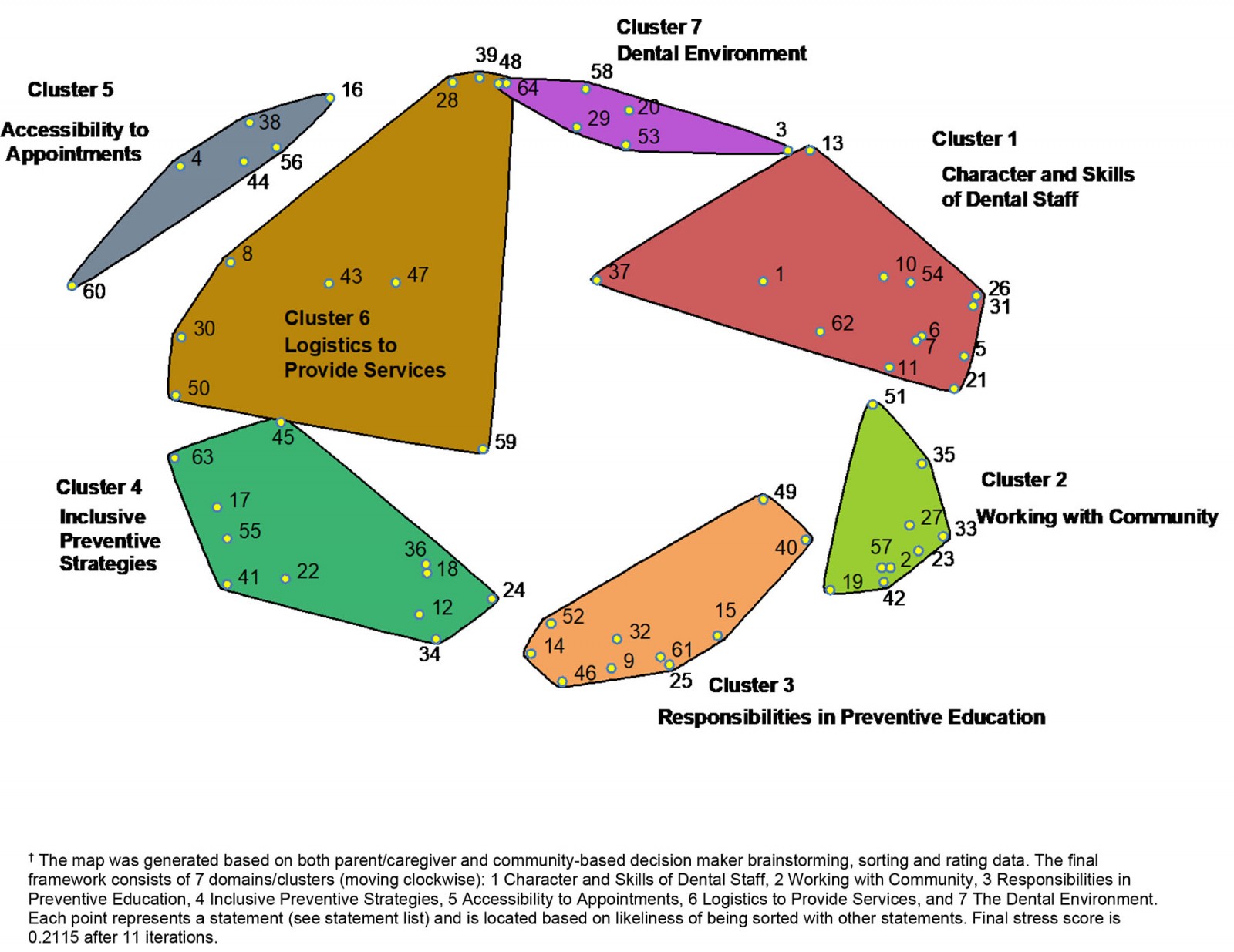

The CG and DM concept mapping data was combined, yielding the combined CG and DM map. The combined CG and DM map was selected as the final concept map, as it included the sorting and rating data input from both the CG group and the DM group. The seven-cluster map was selected as the map of best fit. Then, based on the judgement of items and cluster fitting, 10 items were moved. Labels were determined from the suggested labels from the sorting task and from the labels provided in the CG and DM interpretation sessions. The combined map consists of seven clusters (Fig2, Table 6): character and skills of dental staff, working with community, responsibilities in preventive education, inclusive preventive strategies, accessibility to appointments, logistics to provide services, and dental environment. The combined map was used to develop a measurement tool informed by both caregivers and decision-makers.

Figure 2: The final concept map, ‘Quality Preventive Oral Health Services in Our Community’.†

Figure 2: The final concept map, ‘Quality Preventive Oral Health Services in Our Community’.†

Table 6: Final cluster statement list†

The clusters (combined CG and DM map)

Character and skills of dental staff (cluster 1): Cluster 1 touches on patient–practitioner interactions; how dentists and office staff interact with and serve their patients. ‘Character’ refers to the characteristics of the dentist/office staff, who improve quality of care but are not necessarily trained (ie staff who are friendly, open-minded and respectful). ‘Skills’ refers to the competencies of the dentist/office staff to provide quality care (ie communication skills, professionalism, working with disabilities).

Working with community (cluster 2): Cluster 2 focuses on adapting to serve and work with an Indigenous community. Items encourage providers to learn about the community and its history – both in general, and regarding oral health. Examples of this include ‘[being] open to listening to patients’ experiences with dental work’ and understanding the hardships and strengths of the community. Additionally, informing and involving the community are meaningful in working with Indigenous communities, for example educating leadership (such as Band council) on current oral health status, statistics, and history of oral health in the community.

Responsibilities in preventive education (cluster 3): Cluster 3 outlines expectations of preventive programming and the delivery of preventive oral health education. Items discussed targeted preventive education strategies, catering delivery to patients of different ages or stages of life and with different learning abilities, and providing education in different settings or locations. The domain also communicates that oral health should be approached holistically (ie emotional, mental, and financial impacts; risk factors for all aspects of health).

Inclusive preventive strategies (cluster 4): Cluster 4 discusses the inclusivity of preventive care – both at individual and community levels. The individual level includes informing and involving patients/parents in their own treatments and in their child’s treatment, and ensuring that patients/parents understand all information provided. The community level includes involving community members and leadership in oral health planning and building capacity within the community for members to enter dental-related careers.

Accessibility to appointments (cluster 5): Cluster 5 describes barriers to schedule an appointment or reach the dental clinic for oral health care and information. This includes clinic hours, wait times, cancellation policies, priority appointments, and the ability to contact the clinic for information.

Logistics to provide services (cluster 6): Cluster 6 explores the capacity to provide services in the community. This primarily regards the staff and space available, but also includes accessible transportation to reach dental programs and services in the community.

Dental environment (cluster 7): Cluster 7 describes characteristics of the dental office space. Items in this domain describe an approachable environment (eg the reception being ‘safe, comfortable, private, and inviting’).

Discussion

Caregivers and community-based oral-health-related decision-makers of the NHCN used concept mapping to create a framework of ‘quality preventive oral health services’ in a way that is important and meaningful to this First Nations community and potentially to other Indigenous communities. The final framework, visualized in Figure 2 and outlined in Table 6, consists of seven clusters or dimensions of quality care that impact preventive oral health among Indigenous peoples.

The clusters

Character and skills of dental staff (cluster 1): Cluster 1 discusses the competencies of dental staff to provide quality clinical services, but also addresses required competencies to improve the overall safety of Indigenous patients. One point of discussion was ‘ensuring that patients/parents feel confident in caring for their mouth or their child’s mouth’ (statement 7). In preventing dental disease, it is important that the patients feel that they are capable to care for their mouths. This confidence promotes the self-efficacy of patients and continual preventive oral healthcare efforts at home11. Instilling confidence into parents/patients regarding self-oral health practices may dismantle the effects of patient shaming – whereby patients/parents are made to feel ashamed for the resulting health effects of colonization and the systematic barriers that Indigenous communities are faced with25-29. Participants also expressed the need for dental staff to understand patients’ potential dental anxiety (statement 54). With the knowledge and awareness of historical traumas and dental care for Indigenous peoples, learning to calm and create a safe environment for those affected by dental anxiety and dental fear leads into trauma-informed care.

Working with community (cluster 2): Cluster 2 presents unique ideas about quality oral health care and prevention through relationship-building and learning about the First Nations community. Relationship-building in this context does not refer solely to the relationship between the health provider and the parent or patient (such as in cluster 1). It also refers to the relationship with the community as a whole – both professionally and personally. Participants expressed the importance of understanding the ‘culturally specific standards of the community’ (statement 42) – which vary from community to community, as no two Indigenous communities are identical28. The discussions behind this statement brought about various aspects of care specific to the culture and historical traumas of a northern First Nations community in Canada. Participants echoed the relevance of a holistic view of health and wellness, as well as the need for cultural safety training among oral health workers. Developing training for dental professionals and staff has been noted in other research and recommendations to abate the perception of cultural differences as the root cause of this issue28,30,31.

Participants also stated the importance of dental workers who are knowledgeable of the community’s history with dentists and who are willing to listen to patients’ past experiences with dental care (statements 19 and 27). This can build into knowledge of the history and relationships Indigenous communities have with healthcare workers and researchers, as well as the structural policies affecting oral health28,30,32. The inclusion of local leadership in efforts to improve community oral health (statement 35) was also expressed. Building relations with the community will reveal the hardships faced due to the effects of colonialism, but also the strengths of the community. Understanding both is imperative because in order to work with communities for a common goal, there needs to be an understanding of what barriers the community is facing and what strengths are available to build and shape the desired outcomes28. Relaying information to local leadership (such as Band council, the local community health authority) allows for the establishment of good relationships at a community level and for the utilization of the strengths of the community to uplift and engage in oral health care28,33. Overall, connecting with the community and understanding and learning from the history between Indigenous peoples and health care are essential take-aways from this domain.

Responsibilities in preventive education (cluster 3): Oral health education is an essential component of preventive oral health care. Statements grouped in this cluster describe some of the expectations and suggested approaches for oral health education. Many of these statements describe ideas that are well established in preventive oral health care. Examples are providing education on the complications, risks, and treatment options for dental diseases and providing preventive advice when a patient is at risk for worsening oral health (statements 15 and 49), or dental workers providing preventive oral health information in the dental clinic and community (statement 32). Other statements provide insight into improving oral health education in a First Nations community context. Starting from reaching/accessing information, participants expressed the desire for reminders or information relayed over the local radio, as well as encouraging brushing teeth at school (statements 9 and 52). These reflect the successes witnessed from other health programs in the community and the use of kinship within a First Nations community – especially for children – in which caring for the younger generations is seen as a community effort. Participants also called for a more holistic approach – not only in all aspects of health (emotional, mental, spiritual, physical, financial, risk factors) and age ranges (statements 46 and 25), but also incorporating aspects that are specific and important to the community (statement 40). With each Indigenous community being unique, it is important that the care provided is created in a meaningful and holistic approach that is specific to the interconnected needs of that community. Lastly, preventive education can be bottlenecked by accessibility barriers to acquiring accessible oral health hygiene products (eg having oral health knowledge, but not having oral hygiene products). Dental workers and oral health programs have been called on to advocate for accessible and affordable oral health hygiene products (statement 14).

Inclusive preventive strategies (cluster 4): Cluster 4 outlines the act of patient/parent inclusion, as well as building community capacity to provide dental care and take part in decision making for oral health care. At the patient/parent level, participants expressed that patients/parents should be informed and included in the decision making of a treatment plan (statements 17, 63, and 45). There is also a call to increase the number of Indigenous healthcare workers and healthcare training for Indigenous peoples13 (statements 41 and 55). Indigenous sovereignty is a vital component of Indigenous community growth and community health care28. As the leadership and peoples of First Nations and other Indigenous communities become more involved in the planning and implementation of health care and programming, the more appealing, approachable, and accessible these services become.

Accessibility to appointments (cluster 5): Preventive oral health care, in addition to preventing the emergence of dental disease, includes preventing existing dental disease from worsening. Cluster 5 describes the barriers to schedule an appointment or reach the dental clinic for oral health care and information – from physical/time barriers to accessing oral health care. This includes clinic hours (statements 4 and 38), wait times (statement 44), cancellation policies (statement 56), priority appointments (statement 60), and the ability to contact the clinic for information (statement 16). First Nations communities often balance various dire and immediate needs due to many social inequities communities struggle with. Acknowledging and adapting to time and scheduling barriers may include opening appointment slots after work hours or adjusting to a multi-modal appointment system. This will naturally vary between communities and is recommended to be based on community-specific needs.

Logistics to provide services (cluster 6): Cluster 6 explores accessibility via the capacity to provide services in the community. Statements discuss barriers and challenges to the capacity and infrastructure of providing services to the community. This is primarily the staff and space available (statements 8, 27, 38, 42, 46, 58, and 63), but also includes accessible transportation to reach dental programs and services in the community (statement 30). Transportation is a barrier to health services for Indigenous communities, especially for those communities that are further from a city centre1,3. Furthermore, services available in northern Indigenous communities may be limited due to the staff or space available – which can restrict the number of people who can access services at one time, thus lengthening wait times to reach services1,3. These logistical barriers demonstrate the importance of physical access to care to preventive oral health care for Indigenous communities.

Dental environment (cluster 7): Cluster 7 describes the dental office space and the environment that surrounds it. Items in this cluster show similarities to those in the Dental Satisfaction Questionnaire34 – a commonly used tool to assess the quality of dental care. Items that show similarities include ‘cleanliness’ and ‘child-friendly space’ (statements 58 and 53), and the modernness of the office (statement 48). Validity testing of this developed framework has been performed to explore this comparison along with other measures of quality dental care and all domains of this developed framework17.

Accessibility

Many statements in this framework include approachability and acceptability of health services, which are proxies for access to care. Access to care has a substantial impact on the prevention of dental disease. ‘Access’ is a common factor in frameworks and measurements of quality care35-39. The findings in this article parallel with measures of ‘access’ in terms of quality oral health care, while also including an Indigenous public health perspective on accessibility1. Aligning with current measures of quality oral health care, select statements refer to the physical accessibility – including the staff, space, and clinic times available to reach dental services in the community. Other statements refer to the acceptability of services – discussing inclusivity, approachability, and safety of the environment1. In terms of approachability, relationship building is vital to improving the trust and safety of Indigenous communities towards healthcare providers. This includes services that are free of bias, discrimination, and racism; respect the holistic health needs of Indigenous peoples; and are created with the inclusion of Indigenous peoples in the provision of care1. Furthermore, this research reaffirms the importance of approachability in the prevention of disease28,30.

Current state of preventive oral health services

A theme to highlight in this study is the imbalance of primary, secondary, and tertiary forms of preventive services for Indigenous communities. Generally, preventive dental programs and studies cater to reach secondary prevention – early detection of disease and to minimize its morbidity through early treatment of the effects of the disease9. An example of this is screening and fluoride treatments, which seem to be the only preventive intervention thus far to present the highest level of evidence and a high recommendation grade9. In the general population, dental efforts are working towards primary prevention, where the development of dental disease is avoided by addressing the risk factors and determinants of dental disease9. Whereas the general population may be reaching towards primary prevention, Indigenous peoples are still making the transition from tertiary prevention to secondary prevention.

Most oral health care in Indigenous communities generally serves tertiary prevention strategies – services to alleviate complications of existing disease, as well as restoring function and reducing disabilities due to the existing dental disease9. Tooth extractions have long been the norm for many Indigenous peoples32, and unfortunately continue to be the case in some Indigenous communities3,5,11,32. With such high demand for restorative treatment, wait times are longer and diagnoses are delayed, leading to less continuity of care, and decreasing the effectiveness of treatment – with many children undergoing repeated surgery under general anaesthesia for early childhood caries1,40.

Limitations

Participant recruitment and retention had its challenges. All concept mapping sessions were held in-person in Norway House, Manitoba, where the student PI flew in from Toronto, Ontario. Scheduling was limited to the availability of space and participants. Schedules for parents/caregivers are not always predictable, and some participants were unable to attend all sessions of the concept mapping tasks. However, although the sample size was small, it was similar to that for other concept mapping studies41. Upon notification of participant drop-out, the student PI would recruit CG participants by word of mouth at the local mall. The study took place in one community, which potentially impacts the generalizability of the framework. However, the applicability of these findings to other First Nations communities will be explored in future work.

Conclusion

Efforts to improve the oral health of Indigenous peoples remains an important task. Moving forward, it is important to reflect on the quality of care that is provided to ensure that it is done by the standards that Indigenous communities set out for oral healthcare providers. This study defined ‘quality preventive oral health services’ in the context of a northern First Nations community. The resulting framework outlines several dimensions of quality care that impact preventive oral health among First Nations by acknowledging Indigenous social determinants of health. Although our results reflect the needs of a specific First Nations community, this may be applied to other northern and rural First Nations communities, and perhaps to other Indigenous populations.

This framework was translated into a measurement tool to evaluate the preventive oral health services for Indigenous communities17 and assessed through Bombardier’s Assessment of Sensibility42. Ongoing validity testing is being performed among multiple First Nations communities. A naming ceremony will be held with the participating community and its members, as language plays an important role in providing meaning and ownership of the resulting framework.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Bessie Folster, the community oral health coordinator, for her work in recruiting and participant retention; to Marie Ann Chubb for her assistance with participant retention; to the Norway House Cree Nation Radio Station for announcing the study and providing reminders for participants of workshop times/location; and to the NHCN health directors and the parents/caregivers for all of their time, effort, and input.

Funding

Funding for this research was provided by the Nishtam Nipita (My First Teeth) study (CIHR-IIPH Grant No.: PI1-151324; PI Dr Herenia P. Lawrence).

References

You might also be interested in:

2018 - Self-efficacy level among patients with type 2 diabetes living in rural areas