Introduction

There are an estimated 487 500 Australians living with dementia and this is expected to increase to almost 1.1 million by 20581. Dementia is the second leading cause of death in Australia and the leading cause of death of women, accounting for 14 500 total deaths in 20202. Dementia was responsible for 4.4% of the total burden of disease in Australia in 20223. The cost to Australia is estimated to rise to more than $18.7 billion by 20254.

The Australian Government funds the Commonwealth Home Support Program (CHSP) and the Home Care Packages program (HCP) to assist older people to get help at home. The CHSP provides funds for entry-level support for providers to deliver services such as assistance with daily tasks, home modifications, transport, social support and nursing care. HCPs are for those with more complex needs and who require more support; people are allocated to one of four package levels (basic care, low care, intermediate care or high care). The Australian Government also subsidises a range of aged care facilities for those who can no longer live at home.

While home support, care packages and subsidies to aged care facilities are important sources of support to those living with dementia, carers and family, the complexity of multiple approaches has led to considerable consumer frustration due to confusion, several assessments and a lack of accessible information to navigate the system and the cost associated with services5-8. This has led to the introduction of My Aged Care, a central access point to determine eligibility for the CHSP or the HCP and the level of need. Due to the demand for support services outweighing availability, there can be long delays; for higher level packages the wait can be 2 years.

Gippsland is a rural region in south-eastern Victoria, Australia with a population of just over 300 000 people. The region has an older population with a median age of 46 years compared to 38 years for Victoria9. In 2021, an estimated 7488 people in Gippsland were living with dementia10. An estimated 65% of Australians living with dementia live in the community setting, and most of the support they require is provided by informal carers2.

Currently, across Gippsland there are three dementia access support workers, one dementia clinical nurse consultant, one nurse practitioner dementia and one dementia support specialist. Gippsland has 52 residential aged care facilities and, of the approximately 3000 residents, 40% had a diagnosis of dementia11. The region has 89 general practices, six bush nursing services and 39 community health service locations12.

There is a lack of qualitative information on the experience of people living with dementia and their carers2, especially about the specific needs of those living in rural and regional Australia, who often face multiple additional barriers to accessing health and social care services such as geographical isolation, cost of transport, and limited access to specialist services and supports13. Understanding these experiences helps to identify gaps and unmet needs within the health and social care system, and to potentially improve the quality of care and outcomes for people living with dementia in rural and remote areas. The aim of this study was to increase our knowledge of the needs of people living with dementia and those who provide informal or formal support to someone living with dementia in the Gippsland region. The project was a component of Gippsland Primary Health Network's (Gippsland PHN) Health Needs Assessment14.

Methods

The study was based on qualitative interviews, underpinned by an interpretive theoretical framework15.

Participants

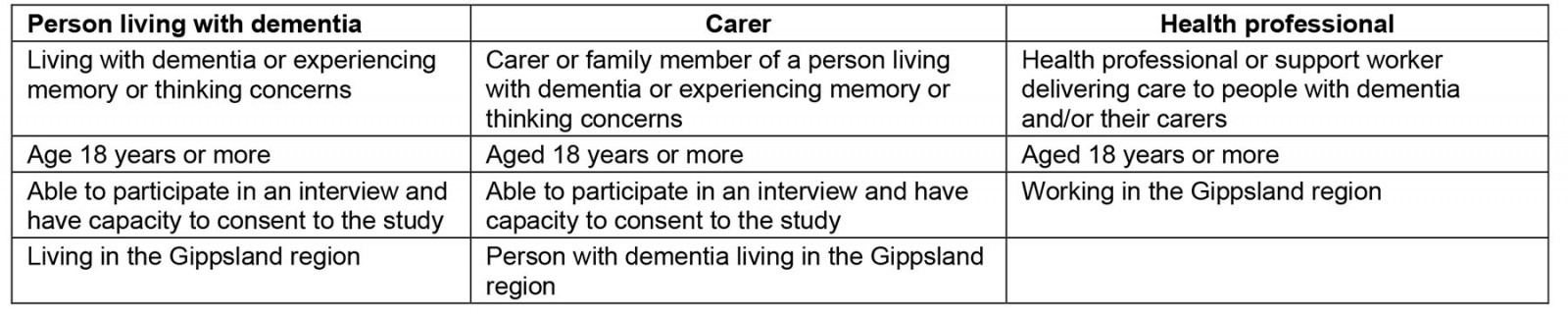

A purposive sample of eligible participants was developed based on the criteria shown in Table 1. This included people with lived experience of dementia, carers of people living with dementia and health professionals delivering care to people with dementia and their carers.

The study was advertised on the Gippsland PHN website, local Facebook pages, emailed news bulletins, local newspaper advertisements and patient referrals from healthcare professionals. Recruitment was supported by two local community health services. Participants were invited to contact a member of the research team, who provided them with information about the study, its purpose, what was involved in taking part and, if they were agreeable to participating, obtained their written consent. When written consent was not possible, verbal consent was recorded upon commencement of the interview. Participants living with dementia were deemed as having capacity to participate when first providing consent and again on commencement of the interview to ensure that they understood what was involved and that they were still happy to participate.

Table 1: Participant eligibility criteria for Gippsland dementia support needs study

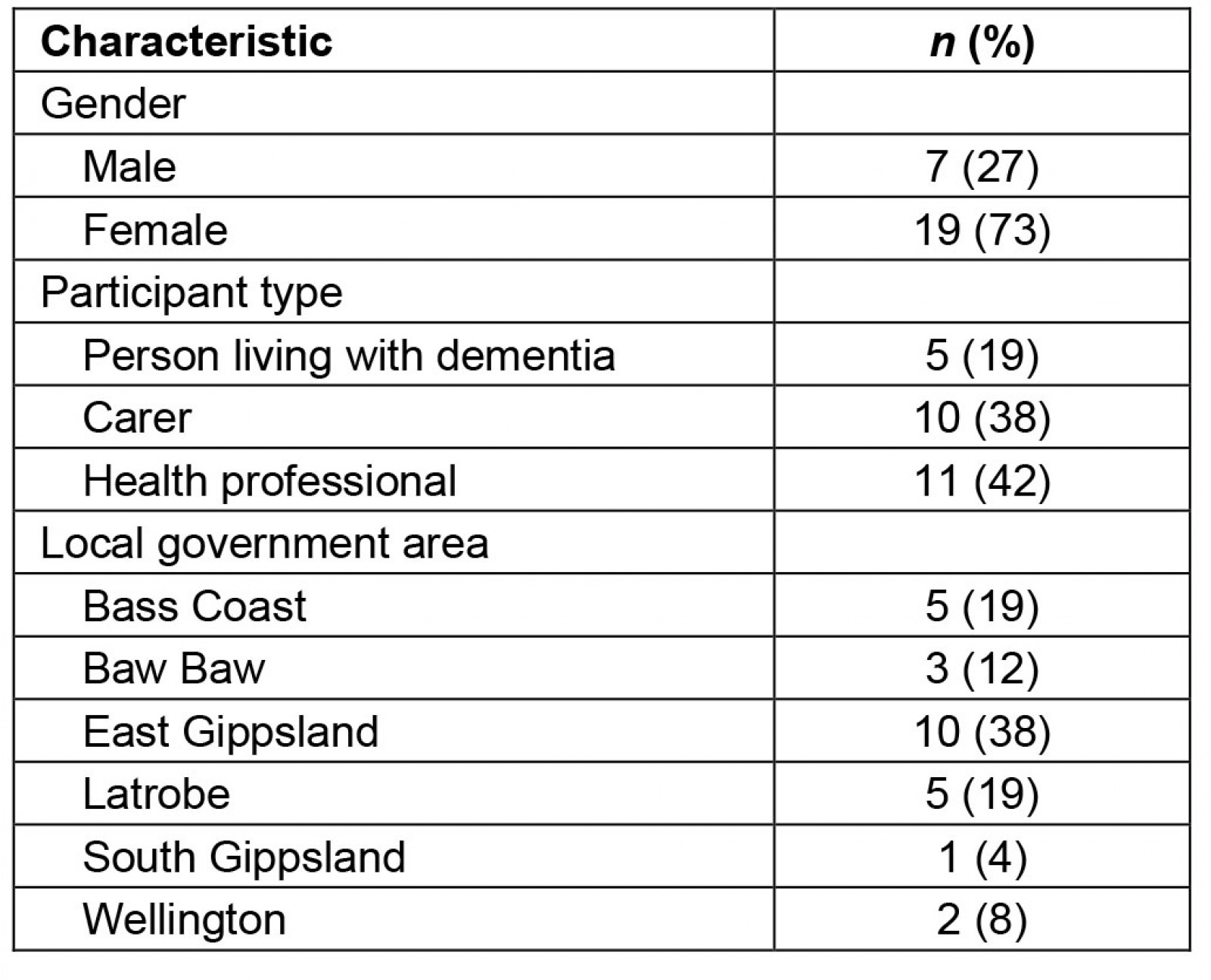

Of 27 people who agreed to participate in the study, one withdrew due to health issues, leaving 26 participants (Table 2). One of the interviews was a dyad, consisting of someone living with dementia and their carer participating together.

Table 2: Study participant demographics

Data collection

Interviews were conducted by the research team (excluding DM, EC and MT) and two members from the Gippsland PHN Community Advisory Committee with personal dementia experience (supported by a member of the research team). All interviewers were female. The research team included three members of the Gippsland PHN Health Planning, Research and Evaluation team (EC MPsych, MG PhD, DA PhD), a Research Professor from Monash University School of Rural Health (DM) and an Adjunct Senior Lecturer from the University of Newcastle and Monash University who is an experienced qualitative researcher with a background in dementia research (DG PhD). There were no prior relationships between interviewers and participants.

Interviews took the form of a guided conversation. Due to COVID-19 restrictions, they were conducted via the Zoom teleconferencing platform or telephone, according to the participant’s choice. The interviews were undertaken between August and November 2020. Interview duration was between 27 and 93 minutes, with an average length of 52 minutes (± 21 minutes), and this varied by group: 34 minutes for people with lived experience of dementia, 46 minutes for carers and 53 minutes for health professionals. Interviewers checked with participants for any signs of distress during and at the end of the interview, and the Dementia Australia Helpline and Lifeline phone numbers were provided.

The interview guide for people with dementia and carers explored participants’ backgrounds, their experience of living with or caring for someone with dementia, the process of getting a diagnosis and whether this made a difference to their lives. It also explored what support services they knew of or had accessed, how they heard about these services and their experience with services that they had accessed. Participants were also asked what was needed to improve the programs offered, what would help to make their lives better and what was most important to them.

The interview guide for health professionals explored the role of delivering a service for people with dementia or their carers and what difficulties they faced. The diagnosis and management of people with dementia living in the community or in residential aged care was investigated, including any assistance provided to someone who is adjusting to living with dementia and what they thought was most important for people with dementia and their carers.

Data collection continued until data saturation was reached for health professionals and carers. Recruiting people living with dementia proved difficult, and it was not possible to achieve data saturation with this group16.

Data analysis

The audio- or video-recording of the interview data was transcribed verbatim, checked for accuracy and imported into the qualitative software program NVivo 12 (Lumivero; https://lumivero.com/products/nvivo). Initial analysis was thematic: each interview was read through to ensure familiarisation of the content. This was followed by descriptive (participant type, gender and local government area) and topic coding (topics discussed during the interview), generation of coding reports according to participant type and topic and then a line-by-line analysis and theme naming. DG led the coding and produced a codebook, which was provided to the rest of the research team for feedback. A copy of the NVivo project was shared with all researchers.

Data analysis consisted of a thematic analysis using a framework approach16,17. This approach was used to facilitate data-sharing by circulating the matrix to the research team for discussion.

The final analysis process involved group exploration, discussion and interpretation of the data to ensure agreement on the themes and all interpretations of the data were considered. After the research team finalised their interpretation of the data, the resulting themes were circulated to participating members of the Gippsland PHN Community Advisory Committee for feedback.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval to conduct the study was obtained from Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (MUHREC) Project ID: 23161. Participants gave their consent prior to their participation.

Results

Analysis of the interview data revealed that the needs of many people living with dementia and their carers were not currently met. People living with dementia and their carers reported not accessing health and social care due to limited accessibility, not knowing what support was available or difficulties navigating the health and social care system. Delays in diagnosis and in accessing specialist supports were described, as were a lack of focus on holistic care to ‘live well’, stigma in the community and among professionals, and the importance of relationship-centred care.

Providers spoke of not being able to meet the needs of clients due to limited access to specialist services, inadequately trained staff with little understanding of dementia, stigma and a belief that nothing can be done to improve the lives of people with dementia, and gaps in knowledge about what services and supports were available. Staff shortages and the funding model for Medicare-subsidised services and residential aged care were noted as problematic and at odds with the delivery of person-centred care and recently introduced quality standards.

Well-established, positive relationships with health professionals and access to a support person who could provide guidance led to greater uptake and satisfaction with support services.

Limited access to services and supports

Limited access to health and social care services: A range of structural barriers to access appropriate care were reported by people living with dementia, carers and healthcare workers. These included GPs’ inability to access specialists, including geriatricians, and for patients’ issues in accessing GPs, specialist services and support services due to a shortage of workers.

… I think the hardest thing is having specialist support available to us as GPs … for example our physician who was involved in the care of patients with memory issues … recently retired … I haven’t found a solution to that gap yet. (Health professional)

Another reported structural barrier was the difficulty of accessing a GP. The impact of not being able to access specialist and GP care appeared to translate into delays in diagnosing dementia, poor continuity of care and a lack of integrated care.

… we have zero geriatricians … our GPs are reluctant to make a diagnosis … that’s problematic because people seeking a diagnosis have trouble getting one. (Health professional)

… getting a consistent practitioner … dealing with … those four agencies and doctors them not talking together really … me trying to … navigate the system, hold it all together … (Carer)

A common barrier to seeking healthcare support was not having a regular, ongoing relationship with a GP who understood a carer’s immediate needs and addressed their specific concerns.

The last GP I saw … was good as far as my concerns were, but … her focus was more on continence, rather than memory, she was like nah we’re all like that … (Carer)

There was a sense of frustration when the needs of carers did not align with the requirements for service provision and the notion that the situation needed to hit a crisis point before they could receive help.

… he had seven or eight really bad falls … it wasn’t until … ten, eleven years … that the … GP threw his hands in the air and said ‘this is bizarre’ and did a referral … for a proper assessment … she … said this is … Progressive Supranuclear Palsy. (Carer)

… the doctor doesn’t feel … that he [person with dementia] is ready for a nursing home … the doctor just told me on the phone that we have to hit a crisis point where he has a fall or where I get sick and can’t look after him. (Carer)

Gaining emergency support to address challenging behaviours or situations in both the residential aged care setting and in the home was reported by health professionals and support workers, with long delays experienced – even with urgent cases. This was attributed to the operation of a triage system and inadequate staffing. This lack of access to support led to persons with dementia being admitted to hospital mental health services.

… So we’ve got Dementia Support Australia … and … Aged Persons Mental Health … teams … so we reach out to them but … of course the more regional and rural you become the less available those services are … I don’t think they have enough people to work through referrals in a timely fashion … they end up down in the [hospital ward] … you just think it’s awful for them, it means they are essentially locked up. (Health professional)

Lack of knowledge of support services and how to access them: People living with dementia and their carers frequently did not know what assistance or support was available to them or how to access them.

… I just think there needs to be a hand-out or something, when your loved one is diagnosed. … once [we] had the diagnosis, it was like – Now what? … (Carer)

This was also identified by healthcare providers.

… a health campaign or something like that around dementia you know explaining … what services are available, once you’ve got a diagnosis of dementia who can you turn to. (Health professional)

Difficulty navigating and gaining access to support services: Navigation issues around the My Aged Care support services was a barrier, especially for those who were not computer literate or had no one to assist them with computer and internet navigation. It was reported that at times the information was out of date, and it was confusing and difficult to follow up providers due to staff often being unhelpful and sometimes providing contradictory responses.

I must say that I’m not actually completely scrambled but it’s a large amount of stuff there. It’s so complex. … which is just unreadable … I’m quite disappointed by that … (Person with lived experience)

… I get on that machine [computer] and try and use it but every time I touch a button I stuff it up … (Person with lived experience)

Long waits for access to Home Care Packages were also reported.

… the long wait for care packages when families needed more support … for people with advancing dementia then you’ve got them living at risk at home. (Health professional)

Funding models as a barrier to access: Inadequate Medicare reimbursement for GPs was found to be a barrier to receiving a diagnosis of dementia. Some health professionals noted that the GP assessment process took significantly longer than the Medicare Benefits Schedule items allowed for.

… if a person goes to their GP … it quite often takes about 3 hours of assessment … the GPs only get paid for 45 minutes … .so that’s why a lot of them … refer on … it’s a huge barrier. (Health professional)

The funding model for residential aged care was also discussed as problematic and at odds with the delivery of person-centred care and quality standards.

So, the funding model we have now is … all focused on that person’s loss of independence, and it is very much at odds with our current new quality standards, that are trying to focus not just on being person centred, but to try and maximise people’s abilities for as long as we possibly can. (Health professional).

… although it’s supposed to be person centred care, it’s not. I think its driven by funding constraints of the environment … the whole model of how we look after people with dementia, needs a significant overhaul. It depends on staff training, depends on culture of the organisation. (Carer)

Lack of holistic care

Participants reported that there was little opportunity for people living with dementia to engage in meaningful activities and social engagements.

… when we were with [community health service] … before we got the package, we had some beautiful outings with them … to the theatre and things like that. Since we’re on the package … it’s not offered and that’s probably one of the things that would be really good … (Carer)

Lack of enablement: Participants expressed poor access to rehabilitation and restorative care in the region. Service providers were not always able to offer the services to meet client needs.

… the thing that would probably concern me the most is that … whatever the particular service was that would be … available, may not necessarily … meet the needs of the client but there may not be anything else … (Health professional)

It was expressed that there was a lack of focus on providing support for people living with dementia to access assistance to overcome deficits associated with dementia.

I think the magic wand that I would wave is intellectual information about the nature of the illness … (Person with lived experience)

Some health professionals noted that the care or respite workers matched with the patient were often unsuitable.

In home respite … success hinges on the worker who walks through the door to provide the service. Now some are fantastic and absolutely have a real innate gift for working with people with dementia. Others, so much less so, and I’ve heard some horror stories … One involving a worker who lay down on the couch and went to sleep … they just don’t really have any idea of what they can do with him [person with dementia]. (Health professional)

Poor understanding of dementia: Many participants, particularly the health professionals, spoke about a poor understanding of dementia by their peers, community members and carers.

So, I say to staff, well what kind of dementia has this person got? And they look at me and say, what do you mean? And I say, well if it’s frontal, it could affect the personality, so the hardest thing is getting staff to understand the individual and their dementia. (Health professional)

There’s quite a bit online [education] but getting people to actually do that and then again integrate it into their thinking I think that’s quite a challenge ... (Health professional).

… I would take her to the Drs … They were quite dismissive really, and … saying you know she’s old, she’s got dementia … and that was it … I was concerned about her mental health … I think to have a phone number to ring and just say look, are we on the right track … is there a better way we could be doing this? (Carer)

Participants described shortages of well-qualified care workers and how this contributes to a lower level of care provided to individuals with dementia. A flow-on effect was the perceived inability of some care workers to effectively communicate with people living with dementia.

… we’ve got some fantastic dementia access and support workers, but … it’s just for 3 months … once the person’s got beyond … there is nobody … with the level of skill working in our community to be able to support people. (Carer)

Stigma

A lack of respect, empathy and understanding of people living with dementia was a consistent theme throughout the interviews. This applied both to the community as well as health professionals, support service providers and care staff. The resulting stigma was noted as leading to the suboptimal provision of health and social care.

… long and short all they said is yes sir you’ve got Alzheimer’s and you must attend with a relative next time … (Person with lived experience)

… getting that message across that … when you get a diagnosis of dementia you don’t plummet off a cliff into oblivion, that you can actually, if properly supported you can live well. If we can get that message across to people, they won’t be so fearful of it and GPs won’t be scared of giving it [the diagnosis] because the consequences of them giving it won’t be so profound on their relationship with that client. (Carer)

… if you asked me as a professional what would I like … I’d like people with dementia to have more fun ... laugh. Less stigma, and to be treated as if you still have value and purpose in life by others. (Health professional)

There was also a perceived belief that nothing can be done to improve the lives of people with dementia.

… the hardest thing is getting the best possible outcome for the client … I find it very challenging getting providers to listen to you and not just use the dementia label. Oh they’ve got dementia, you know you can bring a support, any support worker in there. They’re not going to know, they’ll forget. (Health professional)

Value of relationship-centred care

People living with dementia and their carers highly valued their relationship with a dementia support worker, case manager or a person who listened to them and treated them and the person who lived with dementia with respect. These people were more likely to express being satisfied with their lives and the care and support they received compared to those who felt disrespected.

… yeah, we have a case manager [for Level 4 HCP] she always rings me every week sometimes twice a week – ‘is there anything that you need’ – she makes suggestions … that I don’t even think about. (Carer)

… I guess in total we couldn’t be more pleased about the … service we receive [Level 4 HCP] and general help … I’m very appreciative of the system the way it’s worked out … (Person with lived experience)

Well-established and positive relationships with health professionals or a support worker who could provide guidance also led to greater uptake of and satisfaction with support services. This consequently improved the lives of people living with dementia and their carers.

She just opened up this whole new world to me about the support that I could get, and the help that was available … Like Dementia Australia, they had counsellors you could just call up, any time of day or night and they were just there to talk with you about your journey. (Carer)

Discussion

The study findings illustrate that the needs of people living with dementia and their carers, in the rural and regional area of Gippsland, were often not met. While reasons for this included not seeking access to health care or support services, at times it was due to health and service provider failures to identify client needs or their inability to meet or address their clients’ needs. The reasons for the needs of people living with dementia and their carers not being met included not accessing appropriate health and social care due to not knowing what support is available or difficulties navigating or accessing health and social care providers. There were reports of suboptimal care and a lack of focus on holistic care, relationship-centred care and enablement to ‘live well’. Gaps in knowledge and understanding of dementia were also factors, as were stigma and poor community awareness about dementia.

The reasons for providers not being able to meet the needs of clients included issues in relation to limited access to specialist services, including geriatricians; inadequately trained staff with little understanding of dementia; stigma; and a belief that nothing can be done to improve the lives of people with dementia. There were also gaps in knowledge about what services and supports were available, respite workers not being matched to meet client needs, staff shortages and reports that the funding models for primary and residential aged care are at odds with the delivery of person-centred care and quality standards.

Well-established, positive relationships with health professionals or access to a support worker who could provide guidance led to greater uptake of and satisfaction with support services for people living with dementia and their carers.

Many of these findings align with an earlier study in rural Victoria that identified service and support needs for people living with dementia and their carers18. Priority needs align with those identified in our study: improving early diagnosis, training for health professionals to improve their understanding of people living with dementia and their carers, and more community awareness and education to reduce stigma and increase support for carers to improve their health and wellbeing through connections in the community18.

The present study identified additional barriers for participants who indicated that they did not seek access to care or support services. Participants suggested that at times this was due to health and service provider failures to identify patient or client needs or their inability to meet or address their clients’ needs in a timely way. The findings showed that the lack of knowledge of services in the area and not knowing how to navigate services was a barrier to accessing support services for people living with dementia and their carers. This additional unmet need suggest that consumer-directed care may have shortcomings in the area of dementia. In a study with participants 65 years and older living in rural New South Wales and Victoria, Blackberry et al found that while consumer-directed care could work for older people living in larger regional centres with multiple aged care providers, the model was ineffective for those living in smaller rural areas19. Improving awareness of the services available in smaller rural areas and how to access them, as well as the value of early adoption of these services, was found to be useful. While living rurally can have protective effects for the person living with dementia, the social isolation can be exacerbated by a lack of community awareness of dementia and a lack of access to adequate support services. Hicks et al described the perceptions of rural men living with dementia20. The benefits of rural living were highlighted as a sense of connectedness to supportive informal networks, access to a pleasant natural environment and some formal dementia support services. As in the current study, the challenges faced included a lack of awareness of the condition among their communities and families. The current findings also confirm Blackberry et al’s recommendation for local access to independent local advisors and My Aged Care information that is easier for users to understand and navigate19.

The present study highlighted that a shortage of trained professionals including geriatricians and GPs was a barrier to early diagnosis and ongoing treatment for people living with dementia. This is an important finding and it supports the suggestion that optimising the growing nurse practitioner workforce could be a way forward to increase the capacity of delivering dementia-capable care by involving them in the primary care of patients rather than in co-engagement roles21.

Parallel to the present findings about a lack of consistent, high-quality care among the home care workforce, it has been noted that barriers to developing this workforce include low levels of recruitment and retention as well as a lack of formal training22. Sustainability of the workforce and continuity of care could be ensured by advocating for funding. It also involves policymakers working together with service providers, researchers and caregivers to fill gaps in knowledge and standardise competency-based training requirements.

The Australian Clinical Practice Guidelines and Principles of Care for People with Dementia recommend a person-centred approach to the care of people with dementia23. A foundation for this is professionals trained in dementia care, including how to communicate with the person with dementia. This is in line with our finding that the people who were supported by professionals who listened, and who treated carers and the person living with dementia with respect, were more likely to have their needs met. A Swedish study described a model for person-centred care of people with dementia at home24. It found that familiarity had to be established and continually fostered. When familiarity was in place, the care recipient and the home care staff acted as a team to perform the care. This is in line with another Gippsland study of older people that highlighted the importance of good communication, empathy and validation when the older person is seeking health care to prevent a spiral of decline and withdrawal from services25.

In our study, stigma and a lack of community awareness about dementia were identified as key barriers to meeting the needs of people living with dementia and their carers. Previous literature has explored the effects of stigma on the treatment and outcomes for people living with dementia. The definition of Alzheimer’s disease as a ‘confused state between life and death’ can be harmful as it ‘otherises’ the person26. The effects of ‘otherising’ people with dementia in practice are detrimental, such as ceasing attempts to communicate with the patient, withholding life-prolonging treatment and using force to control undesirable behaviours. Another study notes that felt stigma, described as ‘negative self-appraisals and fears regarding the reactions of others’, is more prevalent and detrimental to the person living with dementia compared to enacted stigma, which is active discrimination against the person27. The authors also warn against raising awareness through highly influential spokespeople and campaigns focusing on the pathology as it can lead to a benevolent ‘othering’ of the person with dementia, unintentionally exacerbating felt stigma.

A 2017 survey by Dementia Australia investigated the beliefs and attitudes of dementia and the stigma experienced by people with dementia and their carers28. Ninety-four percent of the sample living with dementia had encountered embarrassing situations because of their dementia and their overall Stigma Impact Scale scores were significantly higher than those of their carers. Social isolation was a common feeling among people with dementia and their carers. Almost 50% of the general public felt frustrated because they were unsure of how to help people with dementia and commented on the general lack of awareness of the condition.

Study limitations included recruitment of participants during the COVID-19 pandemic and amid multiple lengthy lockdowns in Victoria. It is possible that the pandemic impacted the dementia support workforce and access to services; however, participants instead suggested that reported barriers pre-dated the pandemic. Another limitation was that some participants were referred to the study by a dementia support worker or a dementia clinical nurse consultant and were already connected to support services or were members of carer support groups. Additionally, as data saturation was not achieved for interviews with persons living with dementia, potentially some perspectives and challenges faced by this cohort may not have been captured.

Conclusion

Key areas for improvement include increasing community awareness of dementia and available local support, more support to obtain an early dementia diagnosis, increased support to navigate the system, especially immediately after diagnosis and easier access to the right home support services when they are needed. Other recommendations to supporting people living with dementia and their carers include person-centred care across settings, supported by funding models; more education and communication skills training for health professionals; and greater support for and increased recognition of carers.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the invaluable contribution of the participants who shared their insights. Thank you to the organisations who promoted the project and helped with participant recruitment. We also acknowledge Marion Byrne and Susan Kearney, members of the Gippsland PHN Community Advisory Committee, who made this study possible by assisting with interviews and advice during planning and analysis.

Funding

This study was funded by Gippsland PHN.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest for this study.