Introduction

Access to dental healthcare services, whether for preventive or curative treatments, is hard for those who live in rural areas1-4. In Brazil5,6, as in other countries, people who live in rural areas use dental services less than those who live in urban areas7,8. The last Brazilian National Health Survey (2019) revealed that approximately 48% of the Brazilian adult and elderly population used dental services in the year prior to the survey, but this percentage dropped to 35.8% when only the rural population was considered7.

Although dental services should be equally offered by a universal health system, the use of dental services is unequal between different social groups, economic strata, and levels of education9,10. Socioeconomic status is a significant determinant for the use of health services11-13, and there is evidence that this is even stronger in rural areas8. Levels of education and income are socioeconomic factors that systematically determine the use of dental services. Lower levels of education and income are associated with lower use of dental services9, especially in the Brazilian population7,8,11,14.

Place of residence also explains inequalities in oral health conditions. Rurality has previously been associated with tooth loss in Brazilian adults and elderly15-17 and Chilean adults18, higher prevalence of dental caries in Colombian children19 and with the oral health-related quality of life in Brazilian adults6. Furthermore, Peruvian children who do not brush their teeth are more common in rural areas20. Rural populations travel greater distances to access health care than urban populations, have fewer dentists per individual, and have less water fluoridation21. In addition, these populations have lower availability of primary care services8, and more difficulty in accessing early interventions, and educational and preventive activities22,23. In summary, there are differences in health conditions, access to and quality of health care between rural and urban areas24,25.

Each Brazilian rural region has specific characteristics and singularities26,27. The rural riverside populations of the Amazon, in the North Region of the country, live along or close to riverbanks. Their lives are influenced by demographic dispersion, seasonality of rivers (floods and ebbs), and distances. Moreover, these populations face social vulnerability and difficulty in accessing goods and public services27-29. This region is also characterized by lower access to and use of health services30. The latest national surveys revealed that the percentage of dental appointments was lower in populations from the North Region when compared to the South, Southeast and Midwest regions of the country7,31.

The Fluvial Family Health Teams (FFHT) were implemented to increase the coverage and access to health services, including dental services, in these remote locations in Brazil. In the fluvial teams, the health professionals carry out their duties on a mobile fluvial health unit (vessel) and visit the locations intermittently on monthly trips. The community health workers are the only FFHT professionals who live in the rural riverside localities32,33.

Equity in the use of dental services remains a public health challenge34. Investigating the determinants of the use of dental services in remote populations allows identification of intervention opportunities to reduce inequalities in dental care. Given that there are few studies on the rural riverside populations in the Amazon and from other countries, the aim of this study was to assess the utilization of dental services as well as the associated factors in a rural riverside population residing in areas covered by the FFHT.

Methods

This household-based cross-sectional survey was conducted to describe the sociodemographic and health profile of the rural riverside populations who live along the Negro river, in the municipality of Manaus, Amazonas, Brazil.

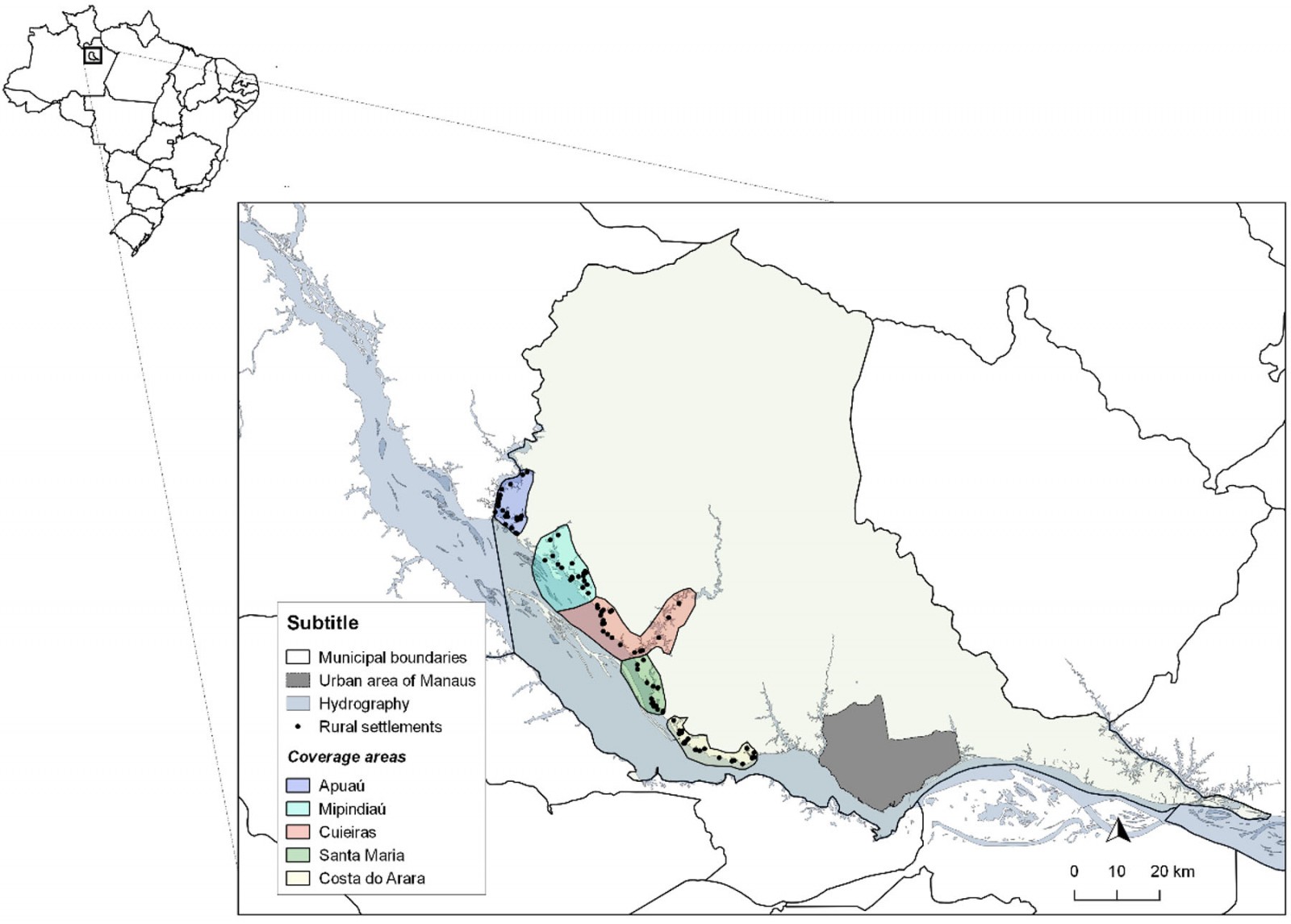

The survey was carried out in 38 rural riverside localities on the left bank of the Rio Negro. The settlements are located in the territory covered by the FFHT and are organized into five areas: Apuaú, Mipindiaú, São Sebastião do Cueiras, Santa Maria, and Costa do Arara (Fig1)25.

Stratified random sampling was performed based on the number of individuals and households in each locality according to information from primary health care, totaling 2342 people in 765 households. The sample size calculation considered the representativeness of adults and elderly of both sexes, and the probability of finding individuals in each household. One adult and one elderly person of each sex from each household were randomly selected, when necessary. The calculation considered a prevalence of 50% of the outcome of interest and a precision of 0.05, in addition to 10% of possible losses or refusals. After this, it was adjusted for the finite population, resulting in 239 households and 509 adults aged 18 years or older. Those with cognitive impairment and who did not have a family member who could respond to the questionnaire were excluded from the sample.

The interviews were conducted using electronic questionnaires developed in the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) v8.11 (REDCap; https://www.project-redcap.org), an open-source application to create and manage surveys and databases. A structured questionnaire with closed questions was administered directly to the participants by trained interviewers. After the interviewers’ theoretical training, two pilot studies were carried out in rural areas of the municipality not included in the main study. The survey included socioeconomic characterization, health conditions, and use of and access to health services.

The main study outcome, dental services utilization, was measured by a question about the most recent dental appointment, with five possible answers: during the past 12 months, more than 1 year to 2 years ago, more than 2 years to 3 years ago, more than 3 years ago, or had never been to the dentist.

The sociodemographic characteristics were gender, age, race/skin color, family income, level of education, recipient of a cash transfer program, and occupation (yes/no). The variables related to oral health were self-reported tooth loss, dental pain and satisfaction with oral health. Self-reported tooth loss was measured using two questions from the Brazilian National Health Survey (https://www.pns.icict.fiocruz.br/questionarios): ‘(1) As for your upper teeth, how many teeth have you lost?’ and ‘(2) As for your lower teeth, how many teeth have you lost?’ The number of missing teeth was the sum of the numerical answers to the two questions, ranging from 0 to 32. The number of missing teeth, dichotomous outcomes of total tooth loss (edentulism), severe tooth loss (up to eight natural teeth) and non-functional dentition (less than 20 natural teeth) were also described. These conditions are not mutually exclusive. The individuals were asked if they had experienced dental pain over the previous 6 months (yes/no). Satisfaction with oral health was assessed using a five-point Likert scale, ranging from ‘very satisfied’ to ‘very dissatisfied’.

The data collected were exported directly from REDCap to a Stata v15 database (https://www.stata.com). After the descriptive analysis, bivariate logistic regression analyses were performed between the independent variables and the outcome of dental services utilization over the past 12 months. Hierarchical multiple analysis analysis was then performed, according to the Andersen behavioral model of health services utilization35. Individual predisposing, enabling and need characteristics defined the three blocks of variables. Variables with p<0.10 at the time of entry into the model were retained in the subsequent models. The level of significance adopted for all analyses was 0.05.

Figure 1: Areas of coverage and rural riverside localities on the left bank of the Negro river included in the study.

Figure 1: Areas of coverage and rural riverside localities on the left bank of the Negro river included in the study.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of FMT/HVD under Certificate of Presentation for Ethical Consideration 57706316.9.0000.0005, and the research participants signed an informed consent.

Results

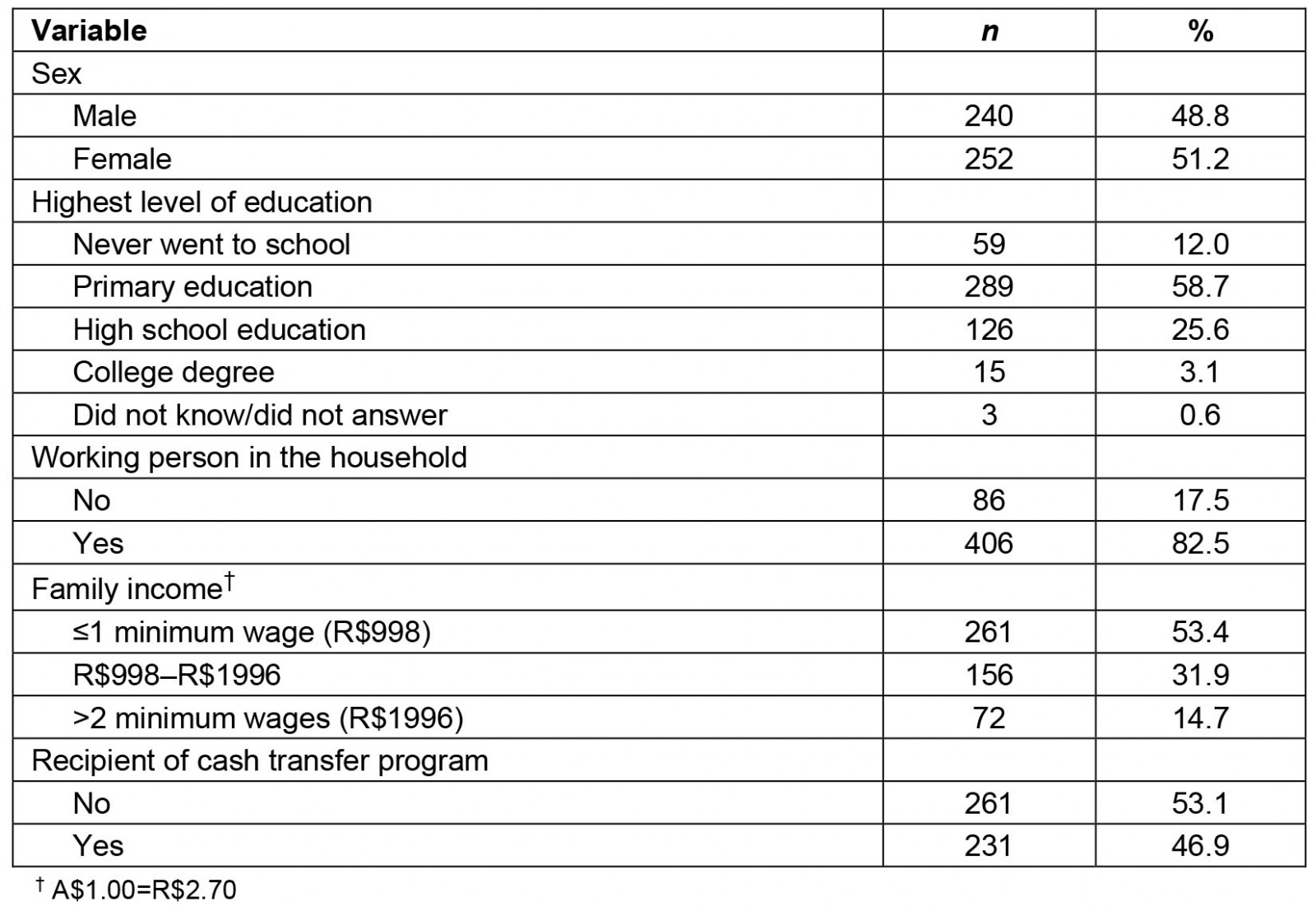

A total of 492 individuals, aged 18 years or more, from 38 rural riverside localities were assessed. The mean age of participants was 43.5 years (standard deviation 17.0), ranging from 18.0 to 90.7 years. Primary education was the highest level of education (58.7%) in the sample and 12.0% of individuals never attended school. Just over half of the population had a household income of less than one minimum wage (53.4%). The sociodemographic characteristics of the individuals are shown in Table 1.

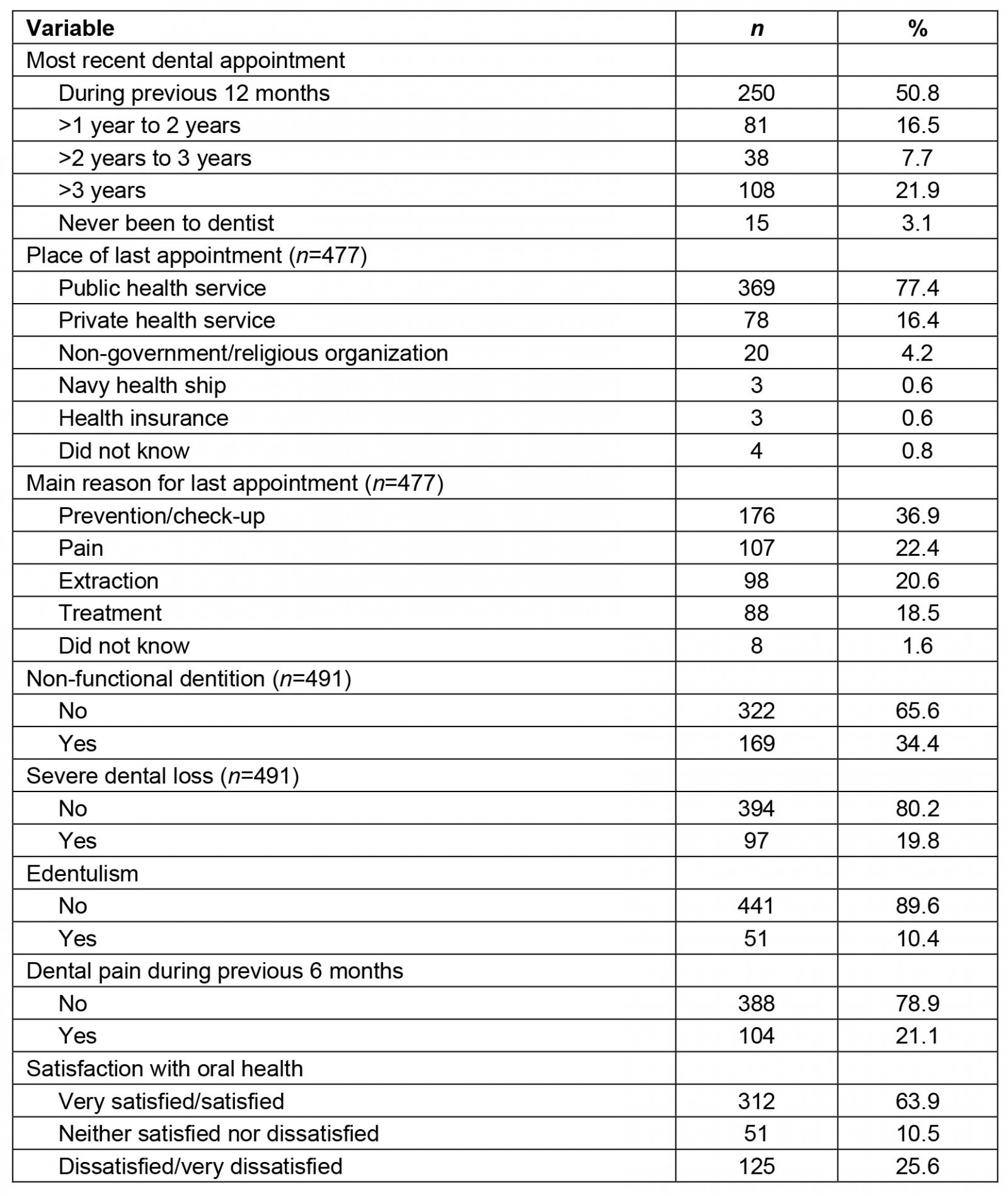

The most recent dental appointment within the previous 12 months was observed in 50.8% of the sample, and 3.1% of the participants reported never having been to a dentist. The most dental appointment was carried out in the public health service for 77.4% of participants, and the main reasons for the appointments were prevention (36.9%), dental pain (22.4%), and tooth extraction (20.6%). The mean number of missing teeth was 10.9, and 34.4% of the sample presented non-functional dentition, 19.8% had severe tooth loss and 10.4% of the population was edentulous. One quarter of the individuals reported being dissatisfied or very dissatisfied with their oral health. Table 2 shows the characteristics related to the use of dental services, and the self-reported and subjective clinical outcomes of oral health.

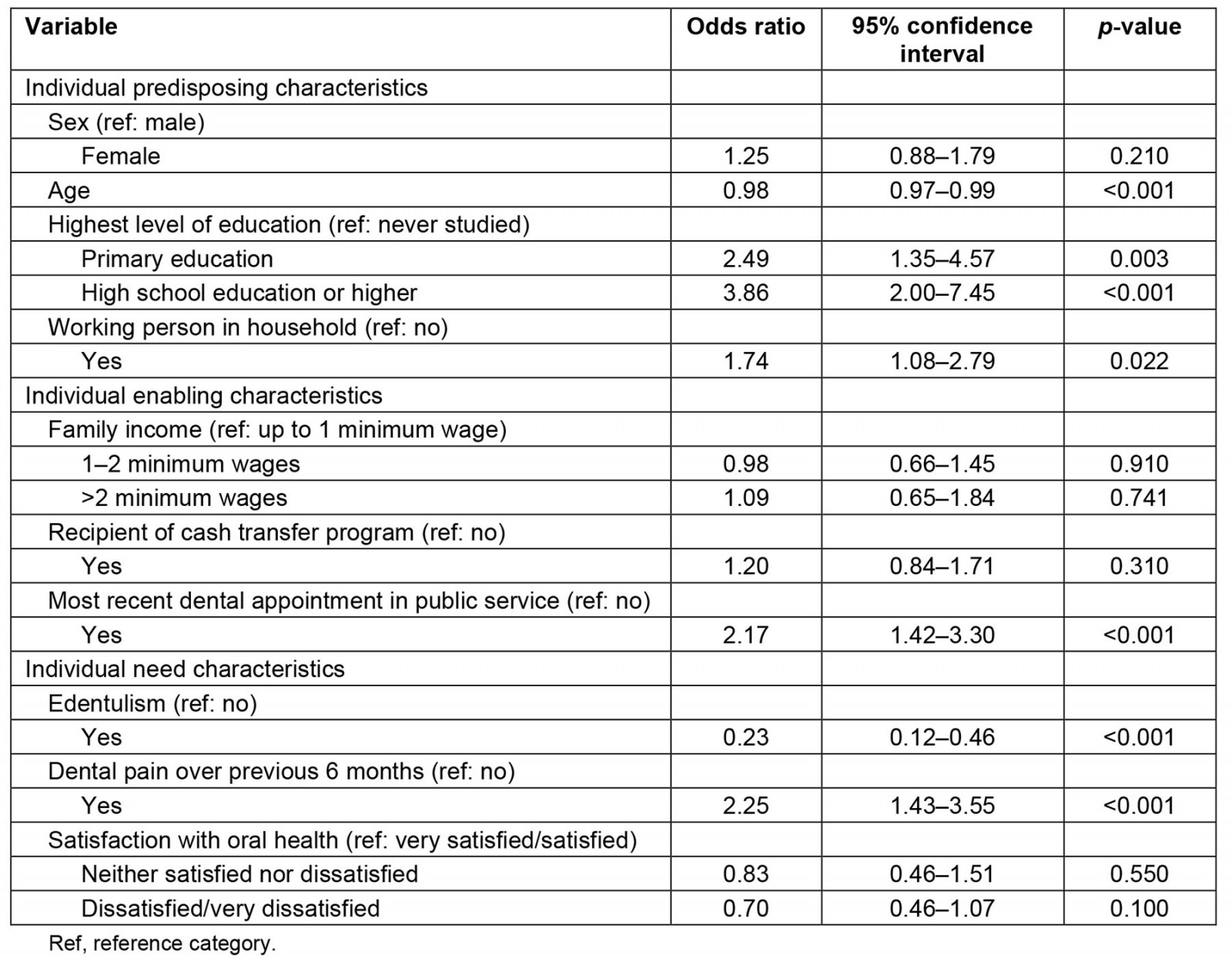

In the unadjusted bivariate analyses, higher education, having an occupation, using public services, and having had dental pain during the previous 6 months were associated with a greater use of dental services within the previous 12 months, while older age and edentulism were associated with a lower utilization of these services. In the adjusted analysis, high school education (OR=2.62; 95%CI 1.18–5.82), having had the most recent dental appointment in the public health service (OR=1.89; 95%CI 1.20–2.97), and dental pain over the previous 6 months (OR=2.44; 95%CI 1.51–3.95), were factors associated with greater use of dental services. Edentulism (OR=0.38; 95%CI 0.17–0.85) and dissatisfaction with oral health (OR=0.6; 95%CI 0.38–0.93) were associated with lower dental services utilization. The estimates obtained in the bivariate analyses are shown in Table 3 and the adjusted estimates in Table 4.

Table 1: Sociodemographic characteristics of study participant

Table 2: Study population use of dental services and self-reported oral health conditions

Table 3: Bivariate analysis between the outcome ‘use of oral healthcare services over the past 12 months’ and independent variables

Table 4: Hierarchical multiple analysis between sociodemographic and oral health-related variables and the outcome ‘use of oral healthcare services over the past 12 months’

Discussion

The study findings showed that a quarter of the rural riverside population in the Amazon region had not used dental services over the previous 3 years, and revealed the relevant role of the public sector for accessing services by the study population. Furthermore, the use of dental services was associated with socioeconomic status and factors related to oral health. Individuals with a higher level of education, those who had had their last dental appointment in the public service, and those who reported dental pain during the previous 6 months were more likely to use the services, while edentulous individuals and those dissatisfied with their oral health reported using the service less frequently.

Approximately a quarter of the sample reported that they had used the service more than 3 years ago or had never been to a dentist. The use of dental services is less frequent in rural areas in various regions around the world1-3,9,36. Socioeconomic inequalities and caries experience were associated with service utilization in Mexico and Peru37,38. In Latin America, when compared to general health care, dental services utilization is lower for both mothers and children39, with maternal engagement increasing the chances of services utilization40. Data from several countries, such as Chile, Brazil, Peru, and Colombia, show a lower likelihood of dental services utilization in rural areas 12,18,38,41.

The national health survey carried out in Brazil in 2013 showed that the use of dental services was lower in rural areas8, although no difference in the adjusted analysis in the 2019 survey was observed7. The first survey showed that, among those who had used dental services, the time interval since the most recent dental appointment was greater among residents in rural areas than among residents in urban areas8. Poor accessibility, issues related to mobility or lack of transportation, limited availability of dental services, lack of professionals in rural areas, and not considering oral health as a priority when compared to other needs such as food insecurity, are all possible explanations for the lower use of dental services in rural areas9,42,43.

The Amazonian rurality, in turn, has singularities that can increase disparities between rural and urban areas. The geographic environment leads to economic and social impacts, and affects access to health services. For the rural riverside population, fluvial barriers make mobility hard due to the great distances between homes and healthcare centers, and the time for travelling has a huge variation according to the floods and ebbs27,30,44. Moreover, the lack of regular public transportation to the urban area and the poor financial resources of the population for transportation also hinder access45. The low availability of health services, the absence of permanent oral healthcare services in communities, and the burden of cost of transportation for riverside people to seek treatment in other locations have been pointed out as reasons why Amazonian riverside populations do not frequently use dental services, as shown by one of the few studies carried out in these populations46. The same difficulties were also mentioned in a Peruvian study that evaluated access to maternal care in a riverside population47. These barriers have negative effects on oral health, as the regular use of dental services is a protective measure against tooth loss in riverside populations in the Amazon48.

Need is strongly associated with the use of health services35. In the present study, the main reason reported for the most recent dental appointment was the need for dental treatment, whether due to pain, tooth extraction, or other reasons (61.5%). Residing in rural areas reduces the probability of seeking dental care to prevent oral diseases, and the use of dental services in rural areas is mainly for curative treatments1,2,46,49-51. In Peru, people living in rural areas have a higher number of caries with pulpal involvement, while in Ecuador and Mexico dental services utilization was associated with pain-related motivations37,52,53. As the rural population faces greater barriers to access dental care, it is assumed that they are less likely to have several dental attendances for preventive or conservative treatments37,54.

A study of a rural US population showed that adults in rural areas were 65% less likely to receive preventive dental procedures than their urban counterparts, and were more likely to receive restorative treatment and indication for tooth extraction2. For a rural population in India, a study reported that dental appointments were motivated by need, either for pain relief (31%) or extraction (54%), and not for preventive dental care55. Dental pain has been identified as the main reason for seeking dental care56-58 both in urban and rural areas55. In the present study, individuals who reported dental pain over the previous 6 months were more likely to use dental services, and more than 20% of the participants reported dental pain within the same period of time. Another study conducted in a similar Amazonian population showed that dental treatment focused on pain relief, particularly by tooth extractions46. The use of dental services is expected when a pain episode occurs59 and longer intervals between dental appointments are associated with a greater chance of seeking dental care due to pain49,57. In rural riverside areas of India, the low availability of dentists, geographic barriers, and lack of transportation hinder the use of services, even in cases of toothache60. Dental pain is mainly caused by dental caries, which is highly prevalent in riverside populations6,60. When dental pain is due to caries, tooth extraction tends to be more frequent because of the limited availability of services, financial limitations of the population, delay in searching for treatment, and the desire for a definitive solution for dental pain46.

The most recent dental appointments in the public health service were associated with the use of dental services. To improve access to and use of dental services in Brazil, an adapted model of primary care was implemented for the riverside populations. The presence, even if intermittent, of the fluvial health unit undoubtedly brings the services closer to the communities. The FFHT, which responds to the specificities of rural riverine localities, operates in areas of great territorial distances and can remain in transit for up to 20 days a month, providing health care to this population61. The fluvial mobile health units are also present in other countries with riverside populations, such as India, Ecuador, and Bangladesh. In general, presence of multidisciplinary health teams and the itinerant regime of the services are similar. However, the model in Bangladesh does not include a dentist in the teams. In this case, dental care is assumed by a dental technician60,62,63. In contrast, in countries such as Venezuela and Colombia, which also have riverside populations, there is no documented evidence in the literature of fluvial units promoting healthcare provision. In such scenarios, populations must journey to areas where these services are available, adhering to the conventional model of health care64, increasing inequities in the healthcare system.

In Brazil, since the implementation of fluvial health units, people who had once been excluded from traditional healthcare models have now been covered by health services, and access to health services has increased, ensuring care for populations in remote and difficult-to-access areas30,65. This finding emphasizes the importance of healthcare approaches directed to peculiar population groups, such as the rural riverside populations of the Amazon66 and other regions with similar populations. However, it is necessary to recognize that, although accessibility to primary health care has improved, the traditional biomedical model of care still prevails, and needs to be overcome30.

The use of dental services by the riverside population was more frequent among individuals with higher education. The association between the use of dental services and education corroborates the literature3,8,9,11,14,50. A higher level of education may be associated with better health literacy67, better understanding of the consequences of health behaviors68, including use of health services35, and higher income69, thus favoring healthier choices70. The school environment and level of education can also strengthen social ties, which have an impact on the use of dental services8. In rural areas of Ecuador, age and education presented a significant effect on self-perceived oral health53. In relation to income, studies on rural populations have found that financial limitations are a relevant aspect for the use of dental services7,8,16. However, in this study, this association was not observed. It can be assumed that, since this is a homogenous low-income population, it becomes difficult to discriminate the impact of income on the use of dental services.

Edentulous individuals and those who were dissatisfied with their oral health used dental services less frequently. A study carried out in a rural population in southern Brazil also showed that a greater number of missing teeth and worse self-perception of health were associated with lower use of dental services16. A recent systematic review revealed that individuals with a poorer self-perception of oral health, edentulous individuals, or individuals with severe tooth loss used dental services less frequently than those with a better perception of oral health and greater number of remaining teeth9. These findings are concerning because they highlight that those who are most in need of dental services do not use them or use them less frequently. It should also be noted that there is a lack of prosthetic rehabilitation for rural riverside populations, which precludes the comprehensiveness of the dental services and comprehensive care.

As this is a cross-sectional study, causal relationships cannot be assumed between the associated factors. Information bias may also have occurred once the data were self-reported. However, although not carrying out a oral clinical examination of the participants can be considered a limitation, the literature shows that self-perception of the number of remaining teeth is a valid measurement71.

The healthcare model offered by the FFHT is a good example of how the specificities of a population can guide the implementation of new strategies for the provision of health services. However, the study findings reinforce the importance of preventive actions to reduce oral diseases, such as dental caries, and the need to reorganize the health promotion model for rural riverside populations, considering the geographical environments, the way of life and the socioeconomic vulnerability. Health and intersectoral public policies that reduce health inequalities and improve access to care, as well as the oral health conditions, are necessary.

Conclusion

The population studied mostly accessed the public service for using dental services, but a quarter of participants had last used the service more than 3 years previously or had never used the service. The main reason for seeking the health services was dental pain and need for tooth extractions. Higher level of education was associated with a more frequent use of dental services. Individuals whose last appointment had been in the public service were more likely to use the service. The use of dental services was less frequent among the rural riverside adults, elderly edentulous and those dissatisfied with their oral health. Although the FFHT has provided an increase in access, the study findings suggest that dental services are centered on illness, reproducing the current hegemonic biomedical model. Therefore, they must be reoriented to meet the specific demands of the rural riverine population, focused on health promotion and prevention of oral diseases, as well as public policies capable of reducing inequities in dental services utilization and oral health conditions of this population.

Funding

The study was funded by the Amazonas State Research Support Foundation (call for projects PPSUS 01/2017), by the ILMD Fiocruz Amazônia PROEP-LABS (call for projects 001/2020 and 025/2022). This project was carried out during the term of the Postgraduate Development Program in the Legal Amazon (call for projects 013/2020), and Program Inova Amazônia Fiocruz (call for projects 004/2022). FJH is a FAPEAM Research Productivity Fellow.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.