Introduction

In Canada, a nation characterized by both geographic and ethnic diversity, the Canada Health Act 1984 comprises terms and conditions established to ensure equity in service access and delivery within a publicly funded system1. Rural and remote communities account for 18.9% of Canada’s population, with longstanding inequities within service delivery, especially with respect to addiction and mental health1,2 leading to delay in diagnosis and treatment, impacting illness severity and outcomes3. A 2019 review of rural mental health services in Canada by Friesen, published as a perspective paper, described different barriers to accessing mental health, strategies for improving access to mental health services, and promising approaches to treatment, including the use of technology4. Employing systematic search methods, the present narrative review was undertaken to further advantage understanding of mental health needs in rural and remote Canada with a focus on non-psychotic psychiatric illness. Prior to specifying parameters and search criteria for the current narrative review, a preliminary, early broad search of the literature was completed.

Rural Canada: definition and demographics

According to Statistics Canada, a rural area is defined as a region containing a population of less than 1000, while a small population center (SPC) is considered to have a population less than 299 999. However, research typically classifies both SPCs and rural centers as rural4-9. Even among communities designated as rural with similar population size and densities, there is great heterogeneity in the values, culture and beliefs that shape each community6,10. Significant diversity can also be found with respect to community cohesiveness, proximity to regional or metropolitan centers, population aging, along with other demographic features11. As an example, with respect to ethnocultural composition, 60% of Indigenous Peoples (First Nations, Inuit, and Métis) live in rural and remote communities while only about a third of non-Indigenous Peoples live in rural communities12. Indigenous Peoples living in rural and remote communities are younger, have lower educational completion and workforce participation rates, all contributing to a significant income gap in comparison to non-Indigenous people12. Additional adverse impacts include the effects of colonialism, residential schools, systemic racism, and intergenerational trauma, all of which contribute to psychiatric morbidity12,13.

While the rural population is growing overall, it is growing at a slower rate than in other areas of Canada because most new immigrants are choosing to settle in urban areas. With rural youth migrating to larger urban centers for employment and educational opportunities, those remaining in rural communities, in particular older adults, experience reduced levels of social support14. While rural communities make significant contributions to the economic growth and prosperity of Canada, these migratory trends have been associated with patterns of economic declines, leading to fewer local resources and services, which necessitates long commutes for essential services8,11,13. Negatively impacting a community’s sense of autonomy, these experiences have been noted to strain community cohesiveness10,11,15.

Mental health service delivery in rural Canada

In rural and remote communities, primary care providers and emergency physicians are crucial in addressing mental health issues given minimal access to other mental health supports13,15. With a lower population density, it is challenging to recruit and retain healthcare providers – in particular those working in specialty areas, such as psychiatrists – in rural and remote areas13,15-17. Access to psychiatric services varies tremendously across Canada, with an average of 13.1 psychiatrists per 100 000 citizens18. As an example, considered as a whole there are 10.6 psychiatrists per 100 000 population in Alberta; however, in Northern Alberta, a predominantly rural/remote region, there are a mere 3.8 psychiatrists per 100 000. Further, these psychiatrists are located in regional centers that provide acute inpatient services, rather than community-centered care18. Similarly, in Ontario and Quebec, despite improved access, most psychiatrists practice in metropolitan centers such as Montreal and Toronto, creating similar challenges in meeting the needs of populations living in remote and northern communities in those provinces18. Rural and remote patients, especially those with low socioeconomic status, have the lowest rates of aftercare, likely related to limited resources to attend appointments in large urban centers16.

Prevalence of psychiatric illness in rural Canada

In addition to highlighting social and healthcare inequities, increasing rates of mental illness and suicide in rural and remote communities calls for innovative, responsive, cost-effective approaches13,19-21. Canadians, both urban and rural, face a 20% prevalence of mental illness and addiction annually, with a lifetime prevalence of 33%19,22. Substance use disorder is the fifth most common reason for hospital admission in Canada after childbirth, COVID-19, and myocardial infarctions and cardiovascular disease23. Although likely underreported due to stigma, rates of mental illness are known to be higher in rural and remote communities, up to two times the national rate3,8,13,24,25. For those who present to the emergency department for psychiatric reasons, most present with both substance use and mental health concerns26. Substance, mood, and anxiety disorders are the most common psychiatric disorders, with lifetime prevalences of 33.1%, 12.6%, and 8.7% respectively; and 12-month prevalences of 10.1%, 5.4%, and 2.6% respectively22. It is well understood that social inequity and socioeconomic factors such as unemployment, inadequate housing, and lack of access to healthcare impact the incidence and severity of psychiatric illness3,8,11,13. Further, since 2020, COVID-19 has aggravated health disparities, with a greater burden of mood, anxiety, and substance-use symptoms among those on lower incomes17. Given the low prevalence and heterogeneity of psychotic disorders, non-psychotic illness was selected as the focus of this study.

Objective

The current narrative review aimed to synthesize findings of previously published research studies and reports on rural mental health, utilizing small population centers and rural within our definition, in Canada, to advance our understanding of risk and protective factors influencing presentation of non-psychotic psychiatric illness and inform development of approaches to responding to mental health needs in rural communities.

Methods

A focused narrative review of relevant research studies and gray literature from October 2001 to February 2023 was conducted to develop a descriptive synthesis of available literature to advance understanding of non-psychotic psychiatric disorders in rural Canada. A wide range of English- and French-language literature was eligible for inclusion including qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods research, reviews, case studies, letters to the editor, and other published reports.

Inclusion criteria

Selected literature was identified as eligible for inclusion if the document: reported on mental health in rural/remote communities in Canada, explicitly focused on primary non-psychotic psychiatric diagnosis (depression, anxiety, substance use, etc.) or consequence (suicide) and/or considered the risk or protective factors or the impact of interventions on non-psychotic psychiatric illness prevalence, incidence, or outcomes.

Search strategy

Several databases were searched to identify published manuscripts, including CINAHL, Medline and Academic Search Complete. Relevant search terms were identified and combined with Boolean operators as per the inclusion criteria and database algorithms. Search terms were as follows: "Rural" or "Remote" communities; "Canada" or "Canadian" or "Canadians" or "Canadian provinces"; "Depression" or "Depressive disorder" or "Depressive symptoms"; "Anxiety" or "Anxiety disorders"; "Substance use" or "Substance abuse" or "Drug use" or "Drug abuse" or "Drug addiction"; "Suicide prevention" or "Suicide reduction" or "Suicide intervention"; "Mental health" or "Mental illness" or 'Mental disorder" or "Psychiatric illness"; "Virtual care" or "Telehealth" or "Telemedicine" or "Telemonitoring" or "Telepractice" or "Telenursing" or "Telecare"; "Text messages" or "Text messaging service" or "Text messaging" or "SMS".

In addition, gray literature, such as Canadian federal and provincial reports, clinical practice guidelines and position papers, was identified by checking reference lists of identified articles and conducting web searches.

After compiling all eligible literature references, duplicate records were identified and removed. Following this, titles and abstracts were screened and, if indicated, the full text of the document was reviewed to ensure its alignment with the specific inclusion criterion.

Charting the data (data extraction)

A standardized template was used to facilitate a narrative synthesis of the collected data. For all included articles and reports, the following information was summarized:

- demographic characteristics of the study population (healthcare providers, community members, stakeholders) – number of participants, age (range and mean age) and setting (Canada, specific province)

- research methods (eg qualitative, quantitative, mixed methods and case studies)

- primary and secondary outcomes – for treatment strategy and innovation articles and type of intervention (primary care, community-based, telehealth, text messaging)

- challenges and recommendations regarding the implementation of the initiative responses.

Data verification and analysis

Preliminary data extraction completed by the first author (JP) was subsequently reviewed and validated as sufficiently descriptive, or flagged for discussion regarding potential revision by PB to ensure descriptive accuracy. Potential discrepancies and inconsistencies were discussed and consensually resolved by the authors. Extracted information from included studies and reports was synthesized in relation to varying emergent patterns associated with different search parameters/categories.

Ethics approval

As this study analyzed already existing published data and did not directly involve patient participants, research ethics approval was not required.

Results

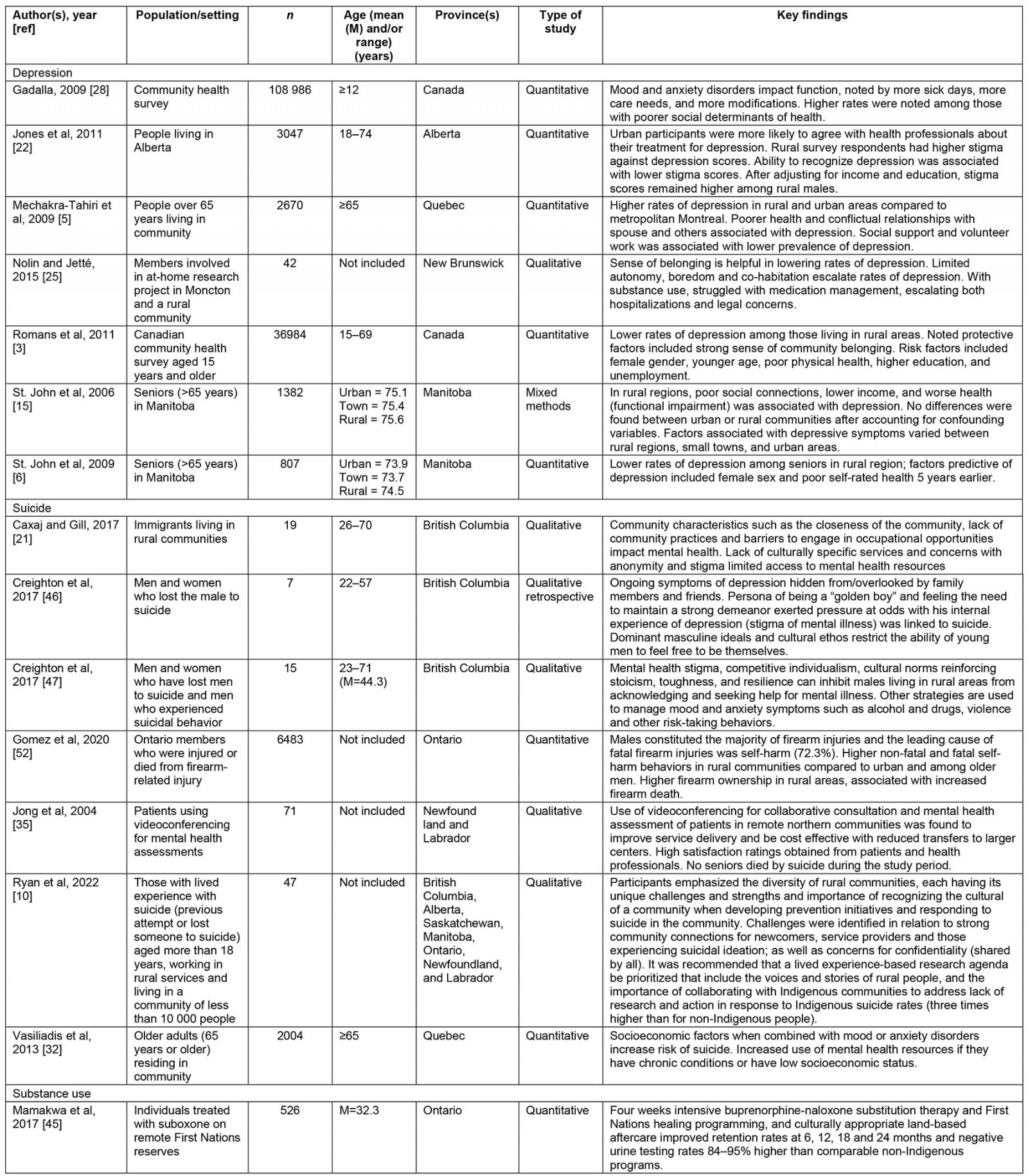

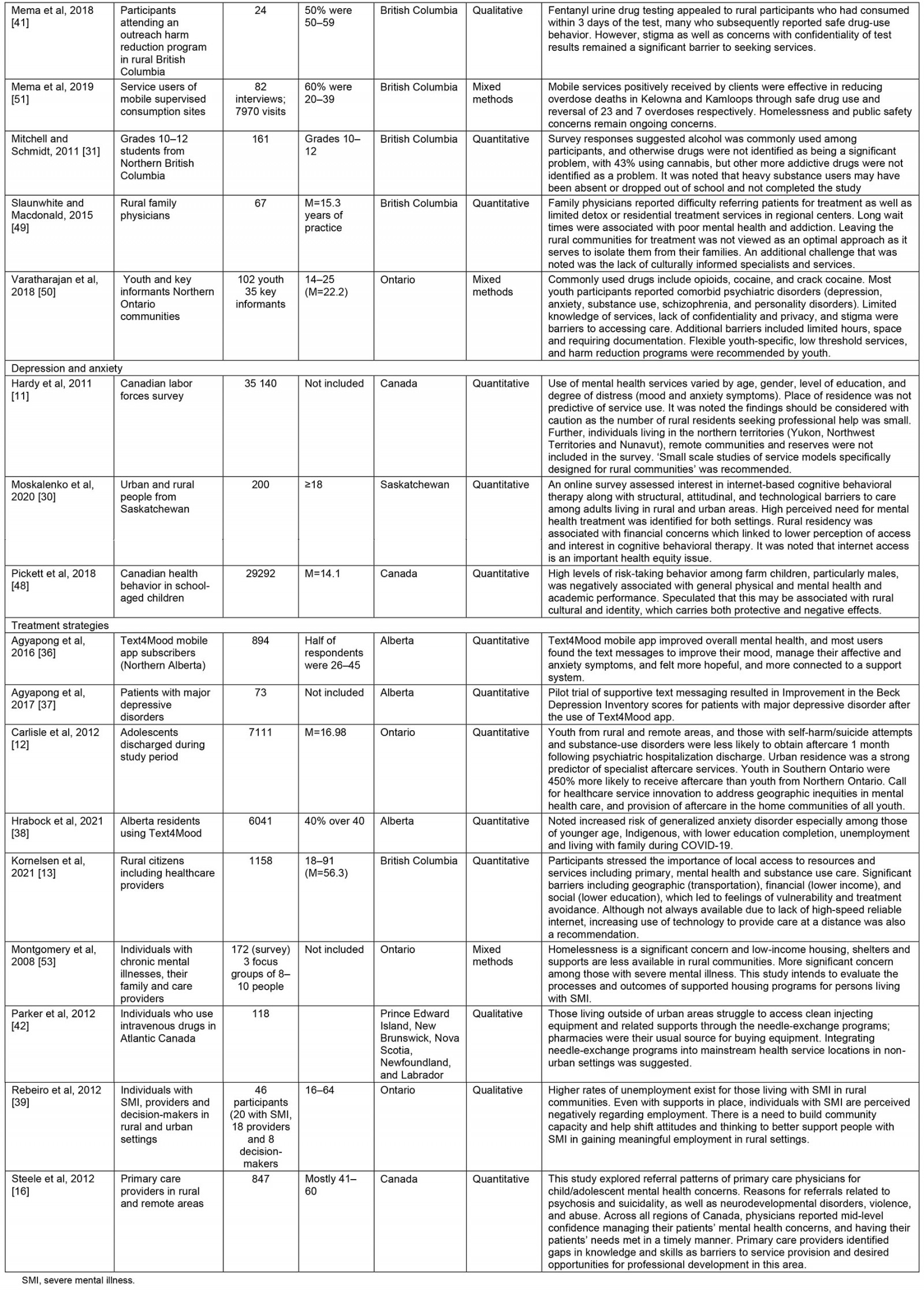

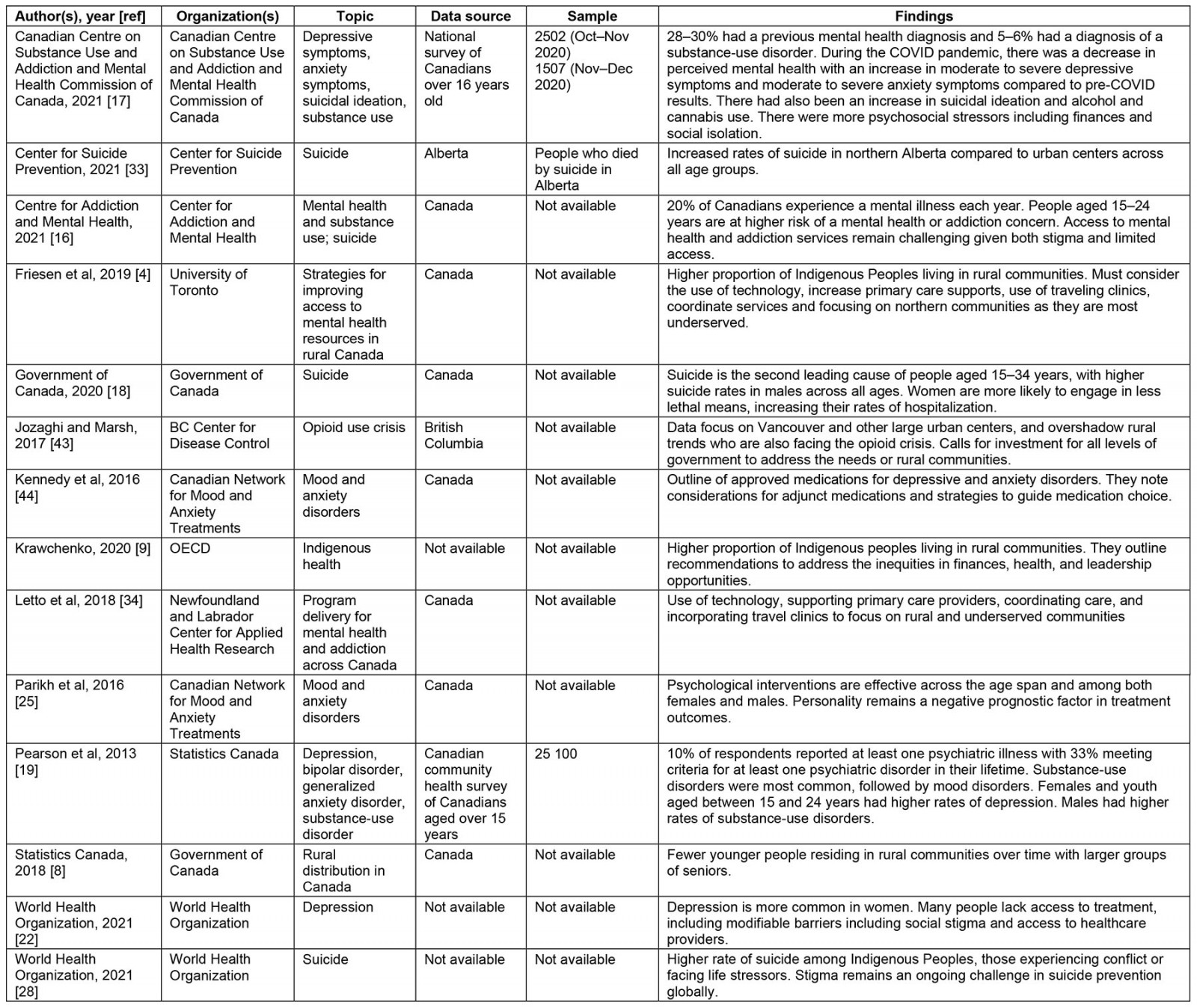

A total of 208 unique articles were published, and 13 gray literature documents were noted between 2001 and 2023. A total of 32 articles (including a number that were identified during the preliminary broad search of literature that helped to inform search parameters for this review) and all additional gray literature documents included in the final data set (Tables 1,2). Included articles and reports focused on specific diagnoses such as depression and anxiety (n=8), substance use (n=6) and suicide (n=7) and/or considered promising treatment strategies and approaches (n=10). In addition to recognizing unique demographic and geographic characteristics of diverse rural and remote areas, several articles addressed this as a specific focus. Barriers and limitations of service delivery in rural communities were also frequently addressed, along with suggested treatment strategies (n=12).

Most of the studies were published within the past 10 years (n=18). About 20% considered mental health across rural Canada, while others included articles and reports focused on different provinces and regions. Of these, most were from British Columbia (n=8) or Ontario (n=6). There were fewer published studies and reports from the Prairie (Alberta (n=4), Saskatchewan (n=1), and Manitoba (n=2)) and Atlantic provinces (n=3). Only one Francophone study, from New Brunswick, was included in the data set.

Table 1: Peer-reviewed published research studies on non-psychotic psychiatric disorders in rural Canada – key findings

Table 2: Gray literature on non-psychotic psychiatric disorders in rural Canada

Depression and anxiety

Globally, depression is a leading cause of morbidity, with personal, occupational, and functional consequences including unemployment, physical and pain syndromes, and self-care deficits3,22,25,27 The data were mixed on the prevalence of depression between urban and rural communities in Canada3,8,11,25,28, and one study suggested depression rates may be up to three times greater in rural communities compared to their urban counterparts, especially for young adults in rural communities with reduced educational, vocational, and lifestyle opportunities, resulting in functional and self-care impairments11. Overall, individuals in rural communities have decreased access to education with lower academic attainments compared to their urban counterparts3,11,17. Similar to urban areas, those who are less educated have reduced knowledge of depression, higher levels of perceived stigma and are less likely to adhere to treatment plans, culminating in worsened outcomes25. Males, especially younger males, often have a higher self-stigma towards depressive symptoms, making them less likely to access mental health supports29. Despite more affordable housing in some rural communities, limited earning potential and reduced job security reduce the likelihood of home ownership3,28. Many rural communities rely economically on resource acquisition such as through forestry, agriculture or oil extraction, the economic instability of which can further the sense of despair and hopelessness30. Given the significant impacts of education and employment, rural members are at risk of depression given an external locus of control, hopelessness, and feelings of inadequacy3,28.

In addition to the wide range of social determinants of health implicated in the prevalence of depression in rural areas, out-migration of youth to larger urban centers is associated with reduced fiscal capacity of rural communities, leading to challenges in providing essential healthcare and recreational services. The resultant need to commute to more urban areas for these services places additional financial strain on members of rural communities11,28.With fewer opportunities for extracurricular activities and facilities, and resulting higher levels of physical inactivity together with the higher cost of groceries, rural members are more likely to rate their physical health as poor3,8,11,28,31, which all contributes to an elevated risk for depression32.

Although rural communities have many socioeconomic risk factors, they also have unique protective factors against the development of depression that can be honed, namely community cohesion and stability of social networks3,11,28. In many rural communities, friendships are long-lasting11. However, for some community members, this sense of community bonds may limit integration, which is especially salient for newcomers to Canada24. Limited social infrastructure, including those supporting religious and cultural practices, can further strain supports available to those with diverse value and belief systems3,25. This dichotomy highlights the need to attend to meaningful community ties and social cohesion for newcomers3,11. Considered together, the biological, psychological, and social underpinnings of depression suggest varied opportunities to mitigate the morbidity and prevalence of depression through policy, health and social service delivery.

Despite the overlap of risk factors for anxiety disorders, including financial, occupational, and interpersonal struggles, research has not identified a significant difference in anxiety disorders between urban and rural areas3,33. However, it is unclear if the prevalence may be underdiagnosed in rural communities, with patients attributing symptoms to physical causes, and recognized by practitioners only at chance levels, given the lack of use and relevance of screening questions33. Similar treatment guidelines have been outlined to treat anxiety and depression given their comorbidity.

According to the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments, the Canadian psychiatric guidelines for management of mood and anxiety disorders, pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic treatments are considered gold standard. These include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), interpersonal therapy and behavioral activation, with a combination of psychotherapy and psychopharmacology being more effective than either alone32,34. Limited health services, including minimal access to psychotherapy and increased reliance on pharmacological management in the treatment of psychiatric illness, calls for innovative models to improve access to non-pharmacologic treatments9,13,24. Recognizing this need, Alberta introduced the Text 4 Mood messaging app for residents of Northern Albertan communities, which provides free daily supportive messages based on the principles of CBT. Many patients have reported an increased sense of hopefulness and connection, along with improvement in anxiety and depressive symptoms27,35-38.

Others have discussed the benefits of virtual care in reducing disparities in mental health care. Various strategies have been implemented in Canada. Urban psychiatrists are using videoconferencing to deliver services to remote communities, helping to overcome financial and transportation barriers13,35,39. Despite initial cost investment, telehealth offers a timely, effective solution for augmenting available services, contributing to overall cost savings for both the health system and the patients and their families, as well as improved outcomes39. This strategy has been effectively deployed in areas connected to large metropolitan centers that have a high density of psychiatrists available to provide such supports13. Other regions such as Nova Scotia and Manitoba have organized a collaborative telehealth initiative involving rural community providers and psychiatrists at urban, suburban, and regional psychiatric care sites34,35. These have demonstrated improved psychiatric outcomes, including adherence to treatment, patient engagement in aftercare treatment, and access to psychotherapy and improved collaboration with primary care physicians16,34,35.

Technology may further provide opportunities to build community capacity by telephone or virtual consultations with physicians and continuing medical education for primary care providers15. Ontario’s Extension of Community Health Outcomes and British Columbia’s Rapid Access to Consultative Expertise program have both demonstrated the increased collaboration among urban and rural practitioners5,35 to support improved evidence-based practices for physicians struggling with optimizing treatment plans and medication management for patients, many of whom may be unwilling to follow through with treatment recommendations for a variety of reasons including lack of understanding, mistrust, and financial pressures5.

Online delivery of CBT, a gold standard treatment for mood and anxiety disorders, is currently helping to extend needed treatment to rural communities that do not have access to other in-person psychotherapy options29. However, some limitations to telehealth have been noted, namely internet accessibility, available providers to organize the clinics and set up the needed platforms, and patient and provider engagement, given the concerns regarding stigma and confidentiality, and upfront costs of the technology13,39.

Substance use

According to the Canadian Institute for Health Information, more than 500 Canadians are admitted to hospital daily secondary to substance use, with higher rates of admission in rural and remote regions in the North (the Yukon, Northwest Territories, and Nunavut)40. Available research suggests high rates of severe substance-use disorder. A propensity to over-value stoicism in rural communities, impeding help-seeking, may lead some to engage in substance use. Although rural community members typically view substance use as adaptive, used to self-medicate and conceal mental health problems, the epidemic of alcohol-use disorder and opioid-use disorder points to unmet psychological and social needs6,9. While access to substances varies between urban, rural, and remote communities, rural and remote areas have limited psychiatric and medical treatment options available to help those with substance-use disorders9,41,42.

With the ongoing opioid epidemic, metropolitan areas have promoted safe consumption sites and other harm-reduction initiatives, while rural communities have largely gone unnoticed despite opioid use rates being up to twice the provincial average6,30,41-43. Attempts at integrating harm-reduction strategies in rural communities have been hampered by concern for anonymity, along with ongoing social inequities such as homelessness9,41,43,44. It is important to note that, even beyond harm-reduction strategies such as needle-exchange programs, additional mental health resources are available and basic needs are met, impacting a person’s interest in seeking treatment beyond the acquisition of substance equipment42.

With the added barrier of having to travel to other communities to seek equipment, individuals in rural communities are at higher risk of using contaminated equipment. Even when members are connected to treatment facilities, many do not attend because of transportation, financial limitations, and familial responsibilities9. Lack of trauma-informed therapy, as well as long waitlists and limited regional sites result in further barriers to concurrent treatment9. The significant physical, occupational and relationship consequences of substance use further exacerbate psychiatric symptoms and hamper accurate diagnoses9. With the innovations in technology, it is important that treatment strategies are culturally sensitive to improve outcomes45. For example, in opioid agonist therapy, combining suboxone with cultural aftercare among Indigenous people improved outcomes above the national average, a significant improvement given their noted lower rates of remission, highlighting the role of healing in treatment45. This highlights the importance of community approaches to reduce stigma and focus on strength-based practices that are community specific, with healthcare professionals in supportive and advocacy roles45.

Suicide

A public health concern globally46, suicide is the second-highest cause of death among those aged 15–34 years in Canada10,18. Although suicide affects all socioeconomic groups, suicide risk is most pronounced among socially vulnerable groups living in socioeconomically disadvantaged areas. Along with broader societal risk factors such as mental illness and stigma associated with help-seeking, challenges within an individual’s community enhance the risk of suicide, including limited access to mental health services, historical trauma, exposure to abuse and violence, and discrimination13,19,46,47. In Alberta, 31% of deaths by suicide occur in the Northern zone, which is predominantly rural and remote communities, despite accounting for only 10% of Alberta’s population48. In both urban and rural communities, men are more likely to die by suicide, whereas women attempt suicide at three to four times the rate of their male counterparts; however, variability in other demographic features suggests risk factors for suicide unique to rural communities21,49,50. For example, in rural communities, there tends to be a collectivist 'stiff upper lip', or attitude of silent endurance24,49,50. Linked to resource extraction and farming, cultural norms emphasizing stoic self-reliance reinforce masculine gender stereotypes13,24,49,50. Stoic attitudes lead individuals to experience shame and guilt around their underlying psychiatric concerns and engage in externalizing, maladaptive behaviors such as substance use, violence, and other risk-taking behaviors24,49-51, which are viewed as more acceptable within the community. Denial of symptoms and fear of stigma prevent engagement with local mental health supports, limiting treatment options24,49,50. Ownership of firearms, which is higher in rural communities compared to urban areas, further increases the risk of suicide, especially among older men52. Concerns with confidentiality also drive individuals to attempt suicide outside their own community10.

Overall, the literature on suicidality in rural and remote Canada is relatively scant and underdeveloped. Further, as noted by Ryan et al, 'Despite the importance of rural culture and experiences of rurality, the voices of those with lived experience of suicidality are missing in current Canadian literature' – voices that could better inform prevention and intervention strategies10.

Conclusion

Over the past decade, advances in technology have led to increased adoption proficiency in use of e-health service delivery approaches, which accelerated following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Many services shifted to virtual options, helping to improve equity in service delivery in rural and remote regions. As previously described by Friesen (2019) in his review of mental health services in rural Canada, technology is a critical tool for addressing gaps in health service provision by engaging clinicians in large urban and metropolitan regions to provide needed specialty support4. Although access to healthcare services is only one of many social determinants of health, having access to care virtually may also address concerns of confidentiality, which poses barriers to accessing local services if they are available. This may also provide opportunities for better collaborative care models with local service providers, including family physicians and allied health professionals. Although some provinces have instituted such models, namely British Columbia and Ontario, these have larger metropolitan centers and a higher density of psychiatrists available to provide rural support, so implementation may be challenging for other regions given the already high demand and limited support resources.

Although virtual options can address care needs, local access to care remains a top priority given improved continuity of care, follow-up options and opportunity to build trust and supportive relationships within communities. Despite attempts to increase psychiatric practice sites in rural areas, most psychiatrists choose to practice in larger metropolitan centers following the completion of their residency training given their familiarity with urban healthcare settings and ease of access subspecialty consultation13. Early training exposure to rural settings, along with increasing adoption of telehealth supporting provision of subspecialty consultation, is needed to promote confidence in practicing in low-resource communities13.

As leaders in health care, physicians are well situated to promote policy and legislative changes to improve resource allocation and address inequities in the social determinants of health impacting rural and remote communities. This includes affordable and safe housing, food and water sources, vocational and educational opportunities, and development of community informed prevention and intervention resources and approaches including Indigenous healing practices and incorporation of mental health literacy. Ensuring access to high-speed internet, recreational opportunities and reliable transportation services are also critical3,4,13,17,24,25,28,49,50,53. Based on this narrative review, it is clear that a multi-pronged, ongoing approach is needed to help mitigate the increased rates, severity, and duration of non-psychotic psychiatric symptomatology in rural and remote regions in Canada3,4,13,17,24,25,28,49,50,53.

Given the underlying personal and community factors, women tend to be diagnosed with depression and seek mental health support more frequently than men46,47. However, at a community level, support for psychiatric illnesses is limited and, even if these supports are available, concerns with anonymity remain pronounced given the interconnectedness of community members24,49,50. There are also concerns that depressive and suicidal screening tools are not eliciting relevant symptoms of rural men, resulting in lower rates of diagnosed depression24,50. Even when the symptoms are present, there is reluctance to disclose such symptoms to a healthcare professional as it would expose the inconsistency between their internal values and their external behaviors50.

Identification of risk and protective factors that are unique among subsets of the population, the experience of women, children, 2S (two-spirit) LGBTQ+ and Indigenous Peoples, especially in rural communities, is underrepresented in the literature10. As demonstrated in this narrative review, many proposed models for responding to mental health needs in rural and remote settings come from provinces with large, well-resourced academic institutions, and a higher density of mental health professionals to draw on, which may not apply in other regions, in particular the northern territories (Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut).

Efforts to promote mental health in rural and remote areas of Canada should be based on a foundation of respectful and meaningful relationships with rural and remote communities, informed by the voices and stories of those living in these communities to develop community-driven strategies for identifying, treating, and supporting vulnerable, at-risk and diagnosed community members. Use of qualitative research to better understand local cultures, and identifying stakeholders, informants, and champions (through local newspaper, radio, and social media), promises to expand relevant knowledge of risk and protective factors associated with psychiatric illness in rural communities, to better inform development of prevention strategies and interventions10.

Limitations

Although mental health and addiction remains a significant global epidemic, research pertaining to rural and remote communities regarding these pressing public health concerns is quite limited. This narrative review was undertaken to summarize studies looking at diagnostic categories of depressive disorders, anxiety disorders and substance-use disorders, rather than unique disorders such as specific anxiety disorders (generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder), specific depressive disorders and specific substance-use disorders, or the functional impairment. The severity of substance-use disorders was also lacking, with most of the literature commenting on severe substance-use disorders, likely underestimating the rate of substance use in communities. The heterogeneity of rural and remote communities may also impact the findings and engagement in research depending on the values and culture within each community. Although narrative reviews have strengths, including addressing a broader scope, the risk of bias from a less robust search strategy and restrictive inclusion and exclusion criteria is concerning.

References

You might also be interested in:

2020 - A mandatory bonding service program and its effects on the perspectives of young doctors in Nepal