Introduction

Approximately 60 million Americans live in rural areas and face a shortage of general surgeons1-4. Currently, only 10–15% of general surgeons practice in rural areas2-5. With only 7.6% of all current medical and surgical trainees across the US in general surgery residency programs, there is no reason to believe the rural surgeon shortage will correct itself without intervention6-8. In fact, given the aging of the population (including physicians), stressors exerted by the COVID-19 pandemic, evolving reimbursement policies, and changing practice models, it is more likely that physician maldistribution and rural physician shortages in the US will worsen9-12. Inadequate access to surgical services has the potential to exacerbate rural health disparities, including gaps in preventable hospitalizations, life expectancy, and trauma mortality13-15. A comprehensive strategy to improve rural health necessitates intervening in the rural surgeon workforce pathway at multiple points, from early exposures to surgery through training and retention.

To address the worsening rural surgeon shortage, economic incentives are often used to recruit surgeons to rural areas. However, these incentives typically focus on primary care and are typically less available to surgeons. While primary care is foundational for population health, evidence has shown that general surgeons and primary care physicians are interdependent in rural areas16,17. Rural general surgeons provide colonoscopies and other preventive care, as well as wound care, caesarean sections, and some gynecology18-21. Much of this would likely be delivered by other surgical specialties in more urban environments. Because of this, debates about adding general surgeons to programs like the US National Health Service Corps are ongoing22. Local economic incentives such as property tax breaks or signing bonuses are sometimes available to surgeons but, although these merit ongoing study, economic factors are not the only influences on practice-related decisions23-25.

Previous research on non-economic rural physician workforce drivers suggests rural upbringing, training location, family proximity, and community size are strongly associated with rural practice choice1,24-33. These associations are well-established, but we know little about the underlying reasons non-economic factors translate into rural practice decisions or whether we have identified the range of factors that matter. Further, it is unclear how non-economic factors may inform interventions at different points in the pathway. These factors may have different effects in early exposures to medicine and surgery, undergraduate and graduate medical education, rural recruitment, retention, and combating burnout. We know a lot of what matters, likely not all, and we need to know more about why factors matter and how we can use them.

Research has previously shown that place-related factors are important to rural health professional recruitment and retention, including local healthcare organization characteristics; social relationships, including a sense of belonging; and spatial characteristics like population density29,30,34,35. While there has been work on rural practice choice, there is little acknowledgment that variation in rural place characteristics may relate directly to variations in the health professional supply. Further, studies using quantitative methods may have limited explanatory power31,36-38. For example, previous survey research found urban and rural surgeons care equally about quality of life36, yet it did not explore definitions of quality of life.

Qualitative investigation into practice location decisions is needed to inform efforts to strengthen the rural surgeon pathway. This work can inform medical educators as they advise trainees, rural communities as they recruit and retain surgeons, and all stakeholders interested in understanding how place-related factors relate to and can be used to alleviate surgeon burnout. To address this gap in knowledge, we conducted in-depth interviews focused on the complexity of place for rural surgeons compared to their urban counterparts. To our knowledge, this is the first study to focus on rural general surgeons in the US and the specific roles of place characteristics in their practice location decisions.

Methods

We designed a descriptive qualitative study39, as this method best allowed us to investigate surgeons’ lived experiences and the range of meanings they may associate with community characteristics. We used convenience and snowball sampling40 in sequence to generate a list of practicing rural and urban general surgeons across the US’ 12-state Midwest region. This approach allowed us to construct a sample with significant variation in geographic location, gender, and age, all factors that could potentially impact how surgeons experience meanings in their communities’ characteristics. The first author contacted potential participants first by email, following up with a second email or a phone call if requested. Participants gave written consent prior to their interviews.

We utilized in-depth, semi-structured interviews to explore: background and upbringing, training, current practice environment, and future plans. Interviews were conducted either in-person or by phone. Because of our focus on perceptions, we allowed participants to self-identify as urban or rural. However, we did cross-reference surgeons’ self-identifications with their counties’ Rural-Urban Continuum Codes (see Results). We asked probing questions about transitions over time: from hometowns to college, medical school, residency and any additional training, then first and subsequent practice locations. Interviews probed for factors influencing training and practice location choices and future considerations. We focused on rural surgeons, using urban surgeons as a comparison group to establish explanatory confidence; without this group, we would have been unable to assert whether rural surgeon findings were unique.

The first author conducted all interviews and used the same interview guide for all interviewees. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Using the constant comparative method to collect and analyze data iteratively, interviews continued until we reached code saturation, wherein new codes no longer emerged41-43.

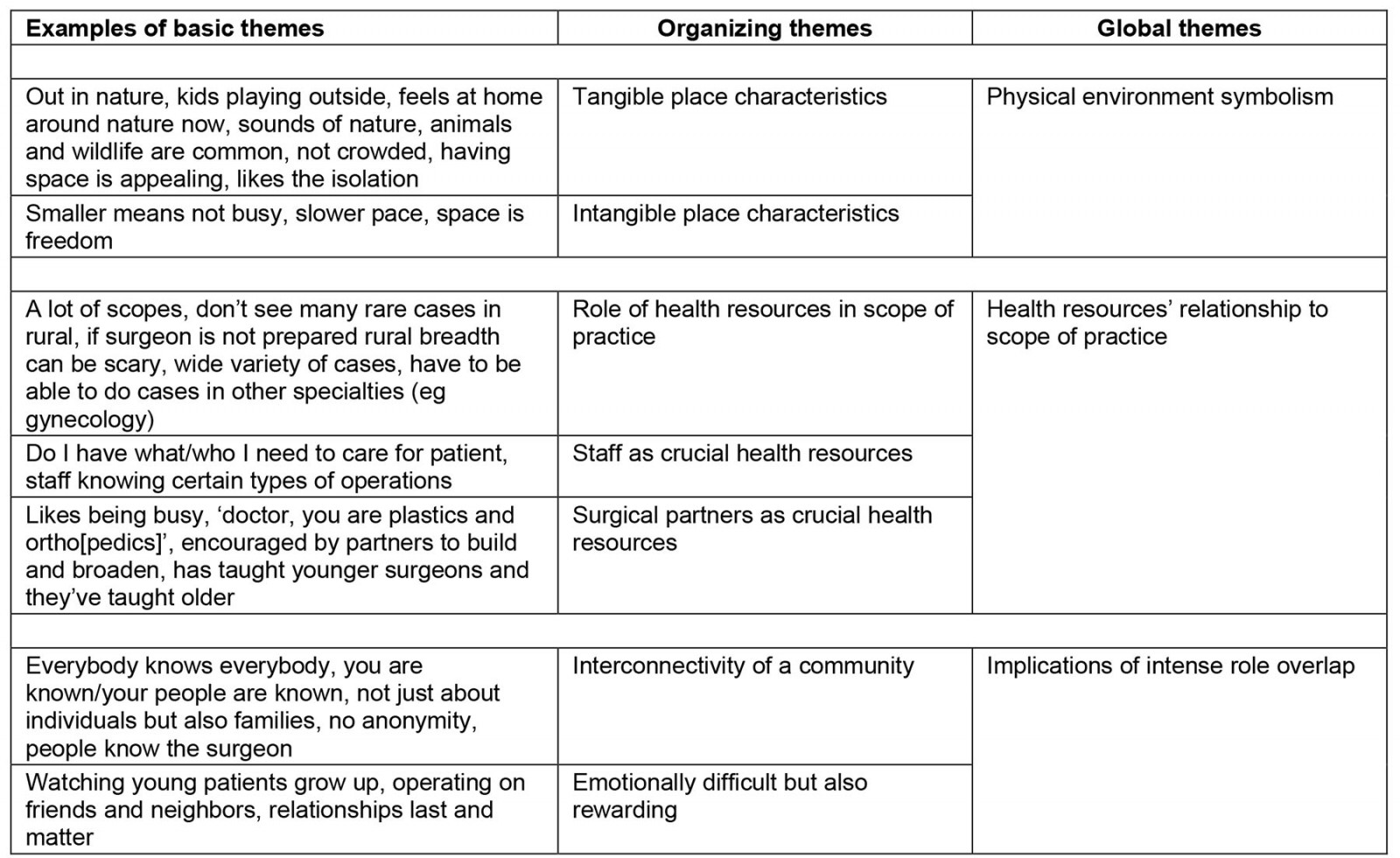

Data were further analyzed by constructing a thematic network44. We assigned basic units of data (individual codes) to organizing themes, then assigned those to global themes. Global themes constituted our primary findings, demonstrating how rural surgeons found meaning in community characteristics differently from urban surgeons and how these differences influenced rural practice location choice. Throughout analysis, the first and last authors discussed coding and analytical decisions, then all authors reached consensus on a final codebook. Our coding, codebook development, and thematic network analysis were managed using NVivo v12 (Lumivero; https://lumivero.com/products/nvivo).

Ethics approval

The University of Kansas Medical Center Institutional Review Board approved this study (STUDY00140707).

Results

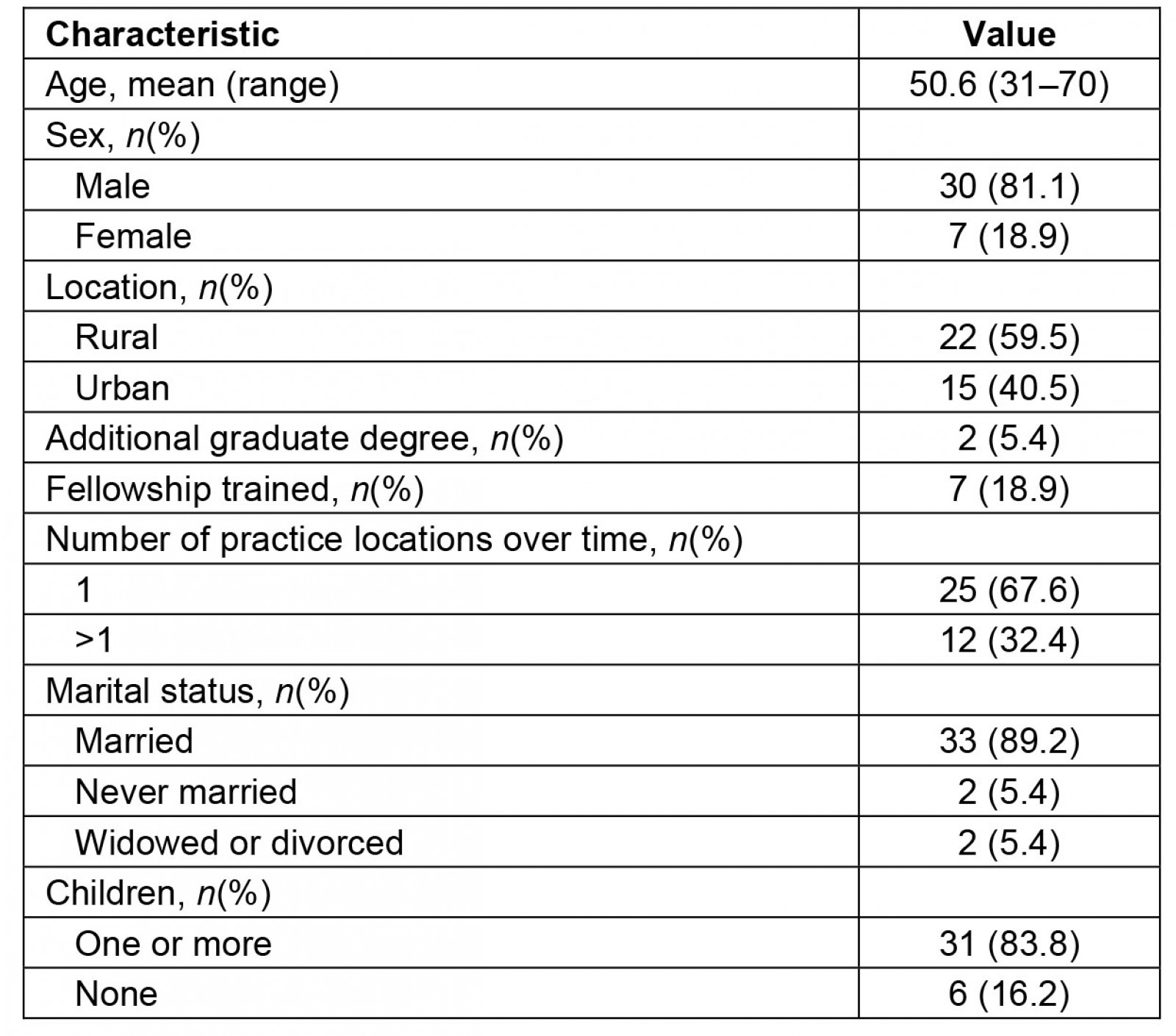

We interviewed 37 general surgeons, 33 in-person and 4 by phone. Interviews totaled over 52 hours (mean: 1 hour 39 minutes). Table 1 provides participant age, gender, location, additional advanced degrees, fellowship training, and number of practice locations (from first location after training to interview date). Social relationships were integral to perceptions of place34, so we included marital status and children to provide context around surgeons’ social selves. Of the 37 surgeons, 22 self-identified as rural and 15 as urban. According to Rural-Urban Continuum Codes, two rural surgeons lived and worked in metropolitan counties. We then looked at these surgeons’ town populations (<1000) and distance to a community with more than 50 000 people (>20 miles (~32 km)). With this additional context, we chose to utilize their rural self-identification for purposes of this analysis.

Three global themes emerged regarding how the meaning of place influenced rural surgeons’ practice location decisions differently: physical environment symbolism, health resources’ relationship to scope of practice, and implications of intense role overlap. Table 2 depicts the progression from basic themes to organizing to global. All themes were present in all interviews, but their meanings differed in important ways between urban and rural surgeons.

Table 1: Participant characteristics (n=37)

Table 2: Basic, organizing, and global themes

Physical environment symbolism

Rural surgeons experienced the physical landscape and community infrastructure as symbols. For example, rural surgeons described how physical space and separation conveyed freedom:

[M]y closest neighbor’s 2 miles away … I like to be out in my yard and nobody’s around. … I think that’s the great appeal with these small-town people. They like farming communities, they grew up out here, and they like the wide-open spaces and the freedom of it, and not feeling like they got neighbors breathing down their neck. (Rural, #8)

This surgeon closely associated open spaces and low population density with an ability to do as they pleased. For other rural surgeons, wide, open spaces and distances from larger communities meant autonomy. They felt able to set their own schedules and priorities, both professional and personal. While surgeons experienced wide, open spaces if they lived outside city limits and while they were between towns, those who lived inside city limits experienced less space between the people and places important in their lives.

Family was a top priority for many and, in small towns, often surgeons’ children were in close proximity. For example, one rural surgeon practicing in their hometown said, ‘[T]he brand new grade school is literally a thousand yards from the hospital. … I can go over there and have lunch’ (Rural, #33). Another rural surgeon, who in contrast grew up in a metropolitan area, also reported their small town size allowed them to spend more time with their child:

When I started practice here, and my daughter was a year old … I thought, if I wasn’t here, I’d be in [big city] or [big city], and I wouldn’t see her. At least here, when I want to see her, I just go home, it’s five minutes. (Rural, #11)

The people they prioritized were frequently nearby, and closer proximity allowed rural surgeons to act on that prioritization more easily, even during a workday.

For rural surgeons from agricultural backgrounds, the physical landscape represented a deep connection to family origins and heritage. One rural surgeon practiced in the same community where their family had farmed for generations. They had trained in a large metropolitan area and practiced there for several years, then returned home. They described a special link between the land and people with an agricultural background:

After 9 years on concrete, grass and trees are important to you, and the first thing I did was plant flowers. Farmers have a, uh, connection, this organic connection to the soil, right? I mean, the smell of soil. (Rural, #6)

For this surgeon, soil was more than soil; it symbolized an ‘organic’ connection to their family’s identity.

Even rural surgeons who were originally from urban areas described an appreciation for open space and nature. Often, they identified the rural landscape as peaceful and contrasted it with the ‘hustle and bustle’ of more urban areas. One rural surgeon from an urban area said their practice location preferences started to shift during medical school:

[T]here were these two lakes, and there was like a little trail …, I think where the transition from being inner-city and wanting to be ‘in the midst of it’ started to shift, where, now I like the peace and quiet, where, I can go and kinda clear my head. … that’s where the shift of me leaving that hustle and bustle and, and wanting to be in the midst of all that, it went away. … I would rather spend my Friday night … out back, sit down, and watch the turtles and wildlife. (Rural, #12)

For this surgeon, it was not a return to their roots or a desire to live near their family that drew them to rural practice. Instead, it was an appreciation for the peaceful outdoors, a slower pace, and the way those place characteristics affected them.

Just as the physical landscape held symbolism for rural surgeons, community infrastructure also conveyed meaning: economic wellbeing. When they were recruited, surgeons observed whether downtown storefronts were occupied or vacant and whether available housing was appealing. They used these observations to assess whether the path they wanted for themselves, their family, and their practice aligned with the community’s trajectory. One rural surgeon described it as ‘synergy’:

[T]he town … passed a school bond issue, and a new high school, new grade school, and invested in the junior high before that. So, 10 years ago, a brand-new football stadium. And then, the hospital board again having big vision …, we have a brand-new OB [obstetrics] wing, sparkly, and we’ll move into new ORs [operating rooms] in three months … [T]here’s a lot of synergy. It’s a thriving place and a lot of forward-thinking folks. (Rural, #33)

For both urban and rural surgeons, vibrancy in the community signaled to surgeons that it could be a place where they could grow professionally, and their family could thrive. Urban surgeons, though, defined vibrancy differently. They rarely discussed community infrastructure or the physical landscape; instead, they focused more on the next theme, health resources.

Health resources’ relationship to scope of practice

Rural surgeons reported that facilities and equipment, staff and staff education, and other physicians and surgical partners were critical health resources. Communities’ unique combinations of quantity and quality of these resources produced different effects on surgeons’ scopes of practice. One rural surgeon said:

[W]hen I got rural, it’s like, okay, it’s not that I can’t do the surgery. Should I do the surgery? … Do I have what I need to take care of the patient around the time of the surgery? (Rural, #34)

They considered their own skill, but it was no more essential than the resources surrounding them. Rural surgeons spoke about how resources affected their decisions about what operations to perform locally and which to transfer to a higher level of care. One surgeon said transfer decisions were one of the most difficult aspects of adjusting to rural practice:

I come from a Level I Trauma Center, and we would call blood bank alerts … what a security blanket. … That’s one thing, and probably the biggest adjustment for me is figuring out when to ship [a patient] and when not to. (Rural, #15)

Blood banks were crucial, and surgeons also raised the importance of infrastructure such as intra-operative fluoroscopy and intensive care units.

One rural surgeon, hired by their hospital to expand minimally invasive surgery, expressed that hospital resources and priorities were a match for their skills and practice plans:

So, I bring another procedure, that hasn’t been done here. I’m only the fifth surgeon in the state that can do it …, that means that I’m right smack dab in this huge circle that could be ours … so, that’s shifting how my practice is going. (Rural, #12)

This surgeon valued offering a service not previously available and recognized their skills were valuable to their hospital from a market competition standpoint.

In addition to facilities and equipment, surgeons emphasized the importance of staff. Staff education levels, training, and experience all influenced surgeons’ patient care decisions, especially decisions about transfers. One rural surgeon said:

When I came out of residency, I could do all kinds of crazy things. I could do all kinds of surgeries, but my hospital, and my staff, could not …. [M]y office nurses didn’t know what a hemi-colectomy was when we started. (Rural, #35)

They had become accustomed to doing a wide array of cases during residency, but they had to think twice after transitioning to rural practice.

While both urban and rural surgeons talked about workloads and call, in rural areas having surgical partners often made or broke surgical practice sustainability:

[T]here’s no way I could handle all of the elective volume, so [part-time partner] offloads the elective volume just enough to where I can keep my head above water. And he comes down one weekend a month … so I get at least one weekend to shut my phone off and coast, 48 hours with my family, which is absolutely necessary. (Rural, #37)

For surgeons not in solo practices, partners meant less call time and more help in the operating room, particularly on complex operations less commonly seen in their areas. One surgeon suggested partners in these situations worked from combined knowledge. Another talked about the burden of call, saying it was not call volume that was stressful but instead the sheer quantity of time on call and how it shaped personal decisions:

[I]t’s not that we get called in that much, because we don’t. It’s the burden of what you can’t do because you’re on call, because of the what-if. It’s the burden of, ‘I’ve got three little kids at home, it’s 8:30[pm], my husband’s still [working], what am I gonna do if I get called in?’ That’s a constant kind of burning that nobody understands unless they take call. (Rural, #35)

For this surgeon, the constant uncertainty and inability to plan – for example, for childcare – was more burdensome than emergency cases themselves. Urban surgeons reported taking call as well, but they more often had more resources at their disposal, such as other surgeons (professionally) or additional childcare (personally).

Urban surgeons also noted the presence of facilities, equipment, staff, and surgical partners. However, they generally spoke about resources as facilitators of their practices, rather than constraints.

Implications of intense role overlap

Rural surgeons described a highly interconnected social fabric as a defining rural community characteristic. It had many implications for them, such as frequent interactions where personal and professional roles overlapped. One rural surgeon described this as ‘living life with your patients’ (Rural, #33). Our results showed surgeons in rural places tended to experience a greater intensity of role overlap compared to their urban colleagues, and this intensity had significance in their lives, sometimes manifesting as humorous encounters and sometimes more somber ones.

All rural surgeons interviewed demonstrated that role overlap was present in their lives but varied in emotional intensity. Variables like how long the surgeon had been in practice, whether they were in their hometown, and town size all factored into whether interactions were more or less emotionally intense. One surgeon originally from an urban area had been in rural practice for less than a year and was still adjusting to the social fabric:

I don’t know who other people are, but they know [me], so there’s this weird, distorted celebrity [status] with it. … ‘Oh, Dr. [last name]!’ It’s like, ‘Hi’, I don’t know you, but, ‘Hey!’ You know? And I have to catch myself to make sure that I’m not doin’ the, the [big city] thing, or inner-city thing, like, ‘Why are you talking to me?’ It’s like, ‘Oh, right, hi, how’re you doing?’ (Rural, #12)

This surgeon was in the process of learning the different social norms and expectations of rural places. Such rural norms also often included expressions of gratitude participants thought would not have occurred in larger, more urban settings. For example:

I learned you had to be careful what you told people you liked. So, one guy, you know, he was appreciative …, a farmer, ‘You like sweet corn?’ ‘Well yeah, but,’ so, one of the Saturdays I came back … there were two sacks, full of sweet corn, leaning against my garage door. … So, my wife taught me how to freeze corn that, that weekend. (Rural, #11)

A gift of food might not be common in every surgeon–patient relationship but, in a rural location, this gesture often found between friends was also common between patients and surgeons. To patients, surgeons were also their friends and neighbors, and vice-versa.

Other rural surgeons reported running errands and finding themselves thrust into their professional role. Patients would approach them and ask questions normally reserved for a postoperative clinic visit, asking about incisions or medications, for example. Rural surgeons often interpreted these interactions as evidence that they were part of the community, not ‘just’ a surgeon but a whole person. Rural surgeons perceived that community members recognized they had value beyond the surgical skills they supplied:

They’re grateful for what you do, most of ‘em. Most of them are super nice, just good country people that still see you as a person, not just a doctor, not just something they need or want done. (Rural, #15)

The interconnected nature of the social fabric meant many rural communities did not reduce their surgeons’ identities to the professional component alone.

At times, though, the tight-knit social fabric was emotionally difficult for rural surgeons. This was especially so for those who returned to their hometowns and had longstanding relationships; operating on people they cared about was no small feat:

[I]t is … a little nerve-wracking … operating on your high school English teacher. … so, it does add a little extra pressure, but, but it’s fine. It’s fine. It was really tough for me at first, but now … I’ve gotten over that a little bit. (Rural, #37)

Evidence from these rural surgeons suggested ‘pressure’ was not necessarily negative but was inherent in the built relationships that extended beyond the surgeon and patient roles.

Urban surgeons did not discuss this kind of interconnectedness in their cities. Some talked about their neighborhoods as mini-cities with some place characteristics similar to small towns. However, for urban surgeons, the professional and the personal spheres of their lives were usually distinct:

What community are you a part of? I’m kind of [city] community, but really like the [employer], and then I’m like part travel soccer team for my son, like that’s my community … I’m part [school name], where my kids go to school. … [M]y communities are like these bubbles around where my kids are and where I am. (Urban, #17)

They recognized their ‘bubbles’ did not typically overlap. This was in direct contrast to the descriptions of social life given by rural surgeons, who described overlapping ‘bubbles’.

Discussion

Effectively addressing any healthcare professional shortage requires understanding the full range of factors impacting practice location decisions, and we found place characteristics critical in these decisions for rural surgeons. We found three kinds of community characteristics that rural surgeons experienced the most uniquely compared to their urban colleagues: physical environment, health resources and scope of practice, and role overlap.

Rural surgeons, regardless of whether they were rural- or urban-born, attached symbolic meanings to rural landscapes. Our data suggest that the attachment of meaning to rural landscapes can occur at any stage, early in one’s life, during education and training, or later. The global themes presented here are similar to those found by Onnis: people, practice, and place45. Our study differs by focusing on surgeons and meaning, delving into ‘people’ by discussing the emotionality of role overlap, detailing ‘practice’ by exploring the implications of health resources for scope of practice and professional fulfillment, and articulating ‘place’ as the deep symbolism of physical environments.

The relevance of rural upbringing to practice location decisions has been prominently discussed in the academic literature and in rural health broadly25-28,31,46-53. Previous work has emphasized the success of ‘recruiting for setting’, in which medical schools recruit students from rural backgrounds, specifically because they are more likely to return to rural areas to practice54. However, our findings show a broader view is merited, beyond a singular focus on upbringing. As prior research has shown, not all rural surgeons were raised in rural areas55.

Research that has focused on the importance of incorporating rural experiences into undergraduate or graduate medical education acknowledges that exposure to rural areas is a key factor in a trainee ultimately choosing a rural practice location31. Our study suggests that rural exposure during training gives an idea of what rural surgical practice is like and also provides an opportunity to discover what the rural landscape and sense of community mean. Rotations and tracks that include living in the community provide an even greater opportunity to witness our third theme: intense role overlap38,56,57.

Surgeons in our study described recognizing signals of economic vibrance. They thought critically about community trajectory and considered whether available health resources aligned with their desired future. Rural communities must assess surgical infrastructure, such as an inpatient hospital and its facilities, the presence of outpatient or same-day surgery, other health professionals involved in peri-operative services, and specialized equipment. In communities lacking the ability to invest in such resources, hopes for local surgical services may not be realistic. These mismatches could set up both rural communities and surgeons for disappointment. Surgery as an economic engine for rural hospitals has been well-studied58-61, and as educators and rural communities work with future rural surgeons, this topic may need to be more explicitly discussed. While community ‘fit’ affected all our interviewees’ practice location decisions, our findings suggest vitality signals mattered more in rural areas.

Communities should consider how landscape, physical environment, health resources, and infrastructure may relate to place attachment, the ‘emotional bond between people and places’34, and its development over time. The symbolism of a rural area’s physical landscape may be apparent to surgeons right away, or meanings may grow in importance or change with greater exposure. Community vitality and surgical infrastructure have a role to play in the development of this emotional people–place bond, as they are linked to surgeons’ personal and professional fulfillment and satisfaction, both key factors in retention. Role overlap is central to place attachment as well and is likely to be impacted by surgeons’ emotional reactions to and sense-making around it.

Our findings showed that role overlap was intense for rural surgeons, who were faced with the difficulty of literally cutting into the bodies of their neighbors and friends. In spite of the difficulties, living life with their patients was deeply meaningful to rural surgeons, a finding in previous research as well26,29,51. The intensity of role overlap was largely viewed positively by rural surgeons in this study, who described being welcomed by their communities for their full selves and not being reduced to their surgical skills. It was intensely humanizing for surgeons and impacted their orientation toward professional and personal pursuits.

There are two points in the surgical workforce pathway where these findings may be particularly useful. In medical school and residency, educators have an opportunity to discuss with students and trainees the complexity of role overlap. These would be appropriate additions to any rural clerkship, rotation, or elective. During the recruitment process, rural healthcare organizations can emphasize to prospective surgeons what value they may find in the physical environment, as well as the health resources the organization offers to support surgery.

Limitations

This study is limited in that selection bias is inherent in convenience and snowball sampling. There is also the potential for recall bias, as we asked surgeons to remember events potentially 50 years or more in the past. However, our goal was to understand feelings that persisted even after the passage of time. This study involved only surgeons practicing in the US Midwest. Since rural areas are not all alike, generalizability to other regions could be limited. Our sample included a range of ages, family situations, and had roughly the same proportion of women as found in general surgery; therefore, it is likely the data are transferable, credible, and dependable62.

Conclusion

This study provided valuable data on the range of community characteristics important in general surgeons’ practice location decisions and the depth of associated meanings. These results may be useful as rural stakeholders work to move workforce trendlines in favor of increased rural access to surgical care. For rural surgeons, the meanings behind rural landscapes were persuasive and pulled them toward rural practice. Healthcare resources were at the core of their decisions about patient transfers and complex case management. These resources and overall community vitality sent powerful signals about whether surgeons could envision a fulfilled future. Educators and rural healthcare organizations should consider emphasizing to prospective rural surgeons the complexity of role overlap. Its presence is unique to rural areas and grows increasingly acute as town size decreases and isolation increases. With knowledge of place characteristics’ meanings and the importance of role overlap, educators and communities can improve surgeon training, recruitment, retention, and burnout.

Acknowledgements

The first author is deeply grateful to the interviewees who generously gave of their time and so candidly shared their life experiences. This work stems from her doctoral dissertation. Co-authors JM and TLG served on her committee, and senior author JVB was her chair. She is grateful for their contributions and those of her other committee members, Dr Glen Cox, Dr Tami Gurley, and Dr Jessica Williams, who were all faculty members in the Department of Population Health at the time of her doctoral defense.

Funding

The University of Kansas Chancellor’s Fellowship supported the first author throughout her doctoral studies; these data were collected as part of her dissertation.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

You might also be interested in:

2010 - Postgraduate training at the ends of the earth - a way to retain physicians?

2005 - Rural nursing unit managers: education and support for the role