Introduction

In breast cancer, surgery plays an important role in treatment1, and a sentinel lymph node biopsy and intraoperative frozen section consultations are essential to confirm the cancer stage and to direct subsequent treatments2,3. However, it is difficult to do so without pathologists. Especially in rural areas, pathologists are not enough to keep up with this demand.

One possible solution is telepathology: performing remote intraoperative frozen section consultation of sentinel lymph nodes using telecommunications technology. In breast cancer surgery, this refers to sending whole slide images of frozen sections to pathologists at other institutions using the internet during surgery to check a resected specimen's condition rapidly. Previous preliminary studies have reported that remote intraoperative frozen section consultation has an accuracy of 92% or better4-7.

The Fukushima prefecture of Japan has been suffering from a shortage of physicians, and this has been particularly prominent in a majority of medical institutions following the 2011 earthquake and subsequent tsunami and nuclear disaster (the 2011 triple disaster)8,9. There was a shortage of pathologists even before the disaster and the number of pathologists in Fukushima in 2007 was 2610, but by 2015, after the disaster, the number had decreased to 2211. In the coastal area of Fukushima, where the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant is located and where the multi-faceted disaster damage has been particularly severe12-14, the situation was especially problematic with pathologists, as only two specialists were available in its area of 2969 km2 and a population of approximately 440 000. Thus, we think that there is much room for improvement in access to the service of pathological diagnosis by implementing the telepathology technique.

The overarching goal of this study was to evaluate telepathology's feasibility in the post-disaster setting of Fukushima. To do so, we aimed to explore accuracy of remote intraoperative frozen section consultation of breast cancer sentinel lymph node biopsy and its required time in the initial phase of introducing telepathology at a leading breast cancer institution in the region. The rural health setting with the diverse post-disaster experience here is unique and provides important lessons for future attempts for telepathology, particularly those related to intraoperative frozen section consultation of breast cancer sentinel node biopsy.

Methods

Setting and participants

This study was conducted at Jyoban Hospital of Tokiwa Foundation, a core hospital in the region with 240 beds and 20 departments. At the time of the study, there were a few pathological technicians, but no pathologists. The breast cancer department has one full-time physician and treats more than 100 patients annually. Since 2019, intraoperative frozen section consultations have been used on a trial basis.

We retrospectively examined the medical records of all breast cancer patients whose surgery involved a remote intraoperative frozen section consultation to find sentinel lymph nodes at the same time as a mastectomy or breast conservative surgery with confirmed pathological diagnosis between September 2019 and June 2020.

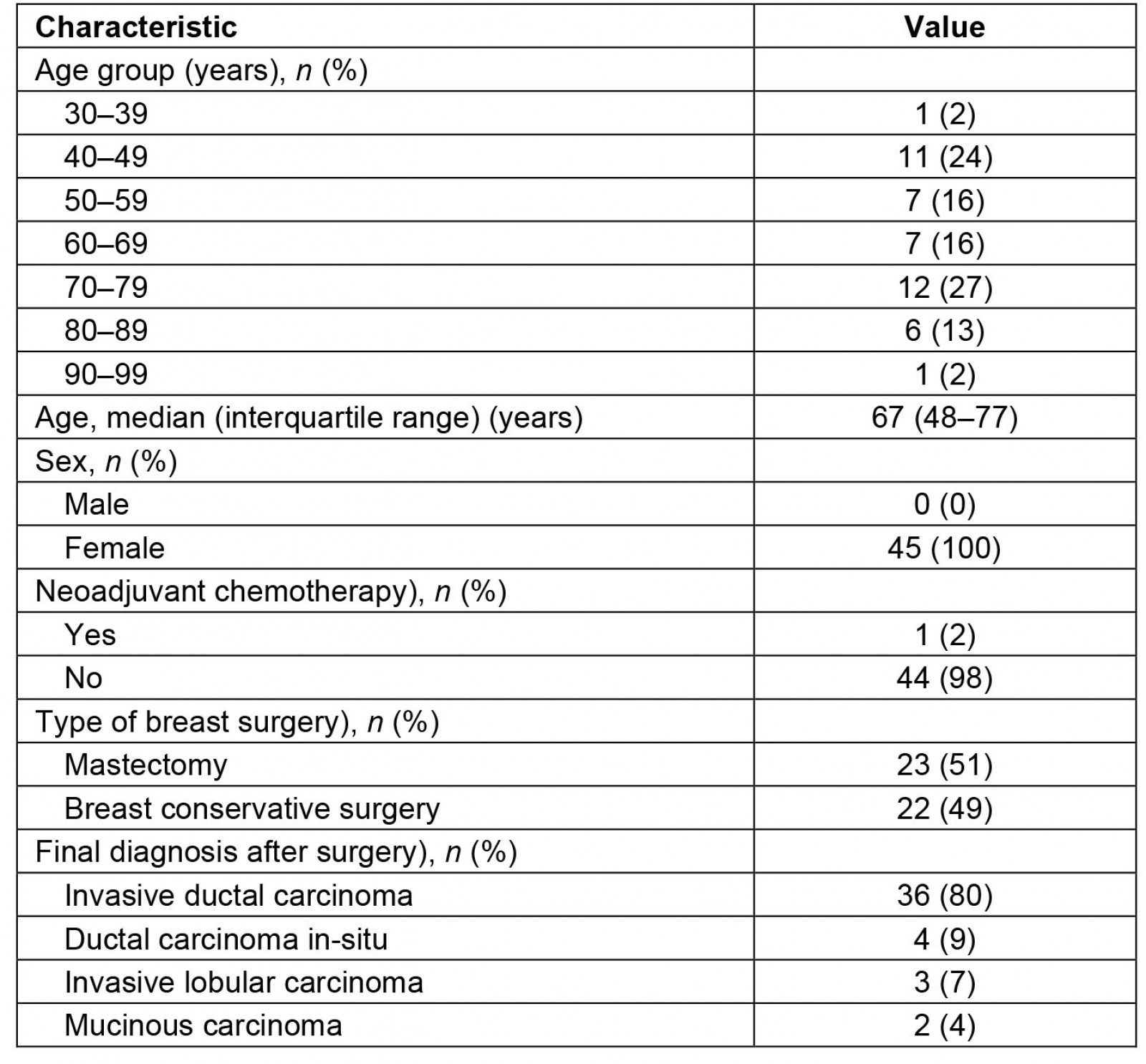

Process of pathological diagnoses, telecommunication technology and related costs

The submitted sentinel lymph nodes, in both systems, were cut at the largest cross-sectional slice for the first few times, and then at a thickness of about 2 mm in the short-axis direction. All preoperative and postoperative diagnoses using paraffin section were made by a pathologist who specializes in breast cancer pathology, visiting Jyoban Hospital once a week. Postoperative diagnoses of sentinel lymph nodes consist of not only inspections of paraffin sections but also of frozen sections made during the surgery.

Telepathology for intraoperative frozen section consultations employed one of two distinct types of telecommunication technology, depending on availability: a cloud-based system (responsibility of Medical Network Systems, MNES) or a simultaneous videoconferencing system (responsibility of Iwaki City Medical Center, ICMC).

For the cloud-based system, we created digital slides for frozen sections of sentinel lymph nodes using the digital scanner Nano Zoomer S210 (Hamamatsu Photonics; https://www.hamamatsu.com/jp/ja/product/life-science-and-medical-systems/digital-slide-scanner/C13239-01.html), which allows a magnification of 80 times at maximum, and uploaded them to the server. This is one of the few systems eligible for reimbursement under the Japanese national health insurance scheme and is considered to enable a comprehensive slide examination of the slides through digital imaging, ensuring a diagnosis that is on par with the traditional pathological diagnosis conducted using a microscope. However, the system may present difficulties in easily focusing on slides with significant thickness.

Pathology diagnoses were made using the viewing software LOOKREC (MNES Inc.; https://mnes-lookrec.com), which allows a magnification set by a digital scanner at maximum.

Eye Vision NEO (ENWA; https://www.enwa.tv/eyevision-neo) was used as the videoconferencing system, cellSens Standard (Olympus; https://www.olympus-lifescience.com/ja/software/cellsens) as microscope image viewing software, and SS-VPN (Shonan Tech, Kanagawa, Japan) as the virtual private network line, specifically prepared for the ICMC and Jyoban Hospital to connect the two hospitals.

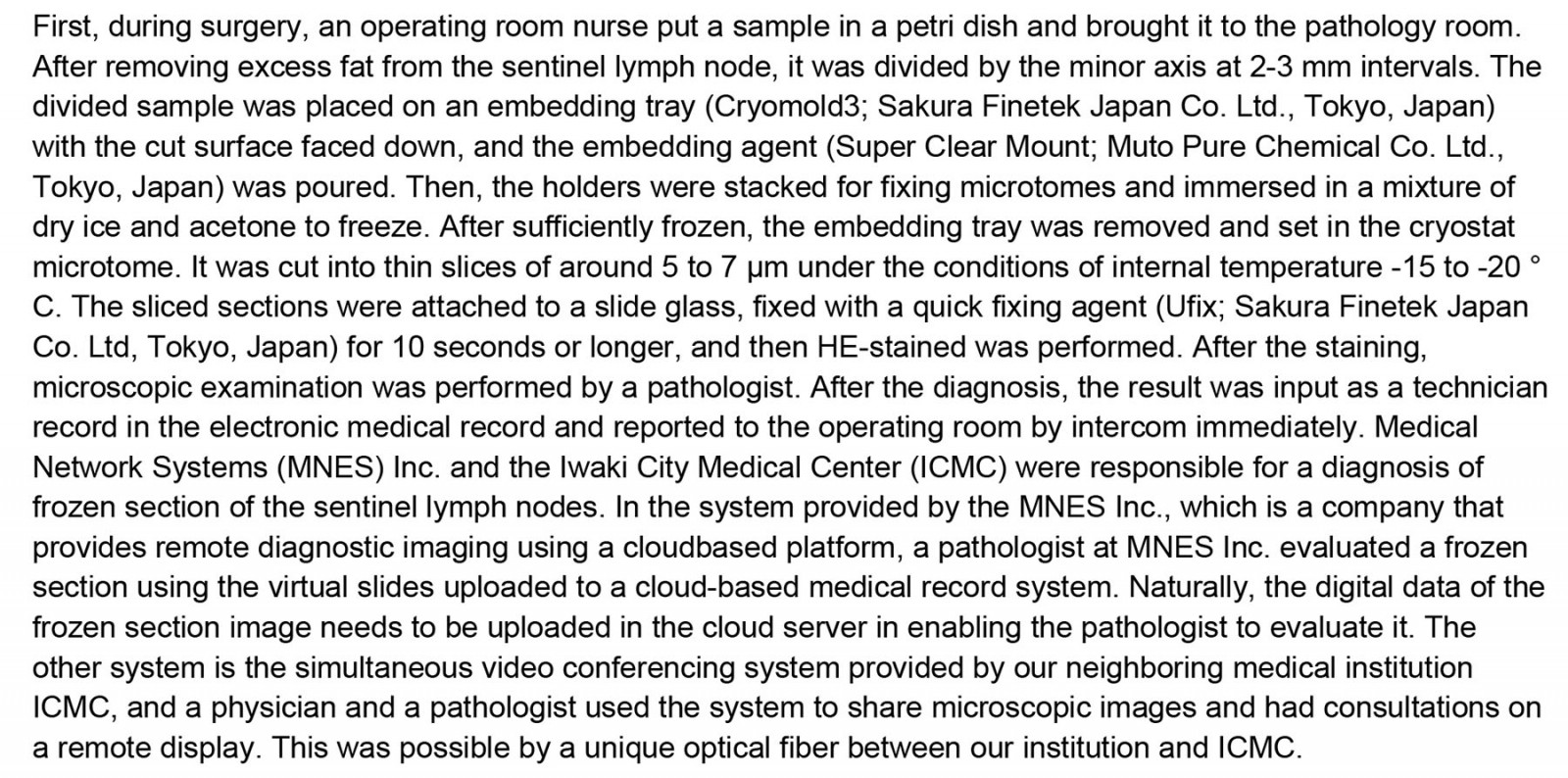

The costs of the systems are shown in Table 1. Other details of intraoperative frozen section consultations using telecommunications technology are summarized in Supplementary text 1.

Table 1: Costs of the MNES and ICMS systems

Data collection and analysis

We collected data on sociodemographic factors including age, sex and clinical characteristics, diagnoses in remote consultation of frozen sections, facilities that performed the diagnoses of the frozen section, and diagnoses in permanent specimens.

First, we compared the diagnoses between remote consultation of the frozen section and the permanent specimen as a diagnostic reference. The accuracy of diagnosis was defined as an agreement of the diagnosis between paraffin and frozen section. We also reviewed digital frozen sections and traditional frozen sections for cases where there were discrepancies between the diagnosis of paraffin sections and digital frozen sections of sentinel lymph nodes, and for which slides were available. Our intention was to determine whether the digital diagnosis had any impact on the intraoperative diagnosis by comparing the diagnoses between digital and traditional frozen sections. If there are no discrepancies in the diagnosis between the two methods, we can conclude that the digital diagnosis did not affect the intraoperative diagnosis.

Second, we calculated an average interval for remote access to the frozen sections, defined as the time from the submission of the specimen to the pathology room to the report of the results to the surgeon. The examination time was calculated using the record of operations.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Jyoban Hospital of Tokiwa Foundation (ID JHTF-2021-007).

Results

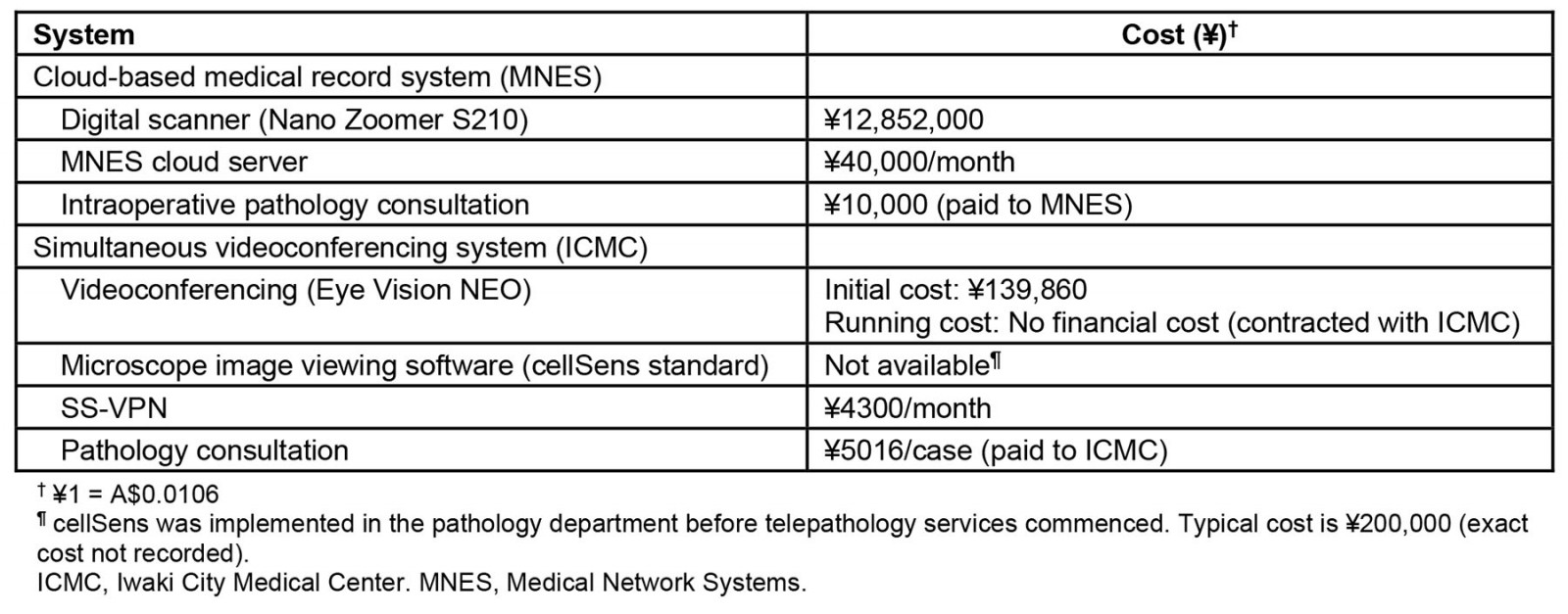

We identified 45 patients within the study period and all of them were included in the further analysis (median age 67 years, interquartile range 48–77, all female; Table 2). Only one patient (2%) received neoadjuvant chemotherapy before surgery, while 23 (51%) received mastectomy and 22 (49%) received breast conservative surgery.

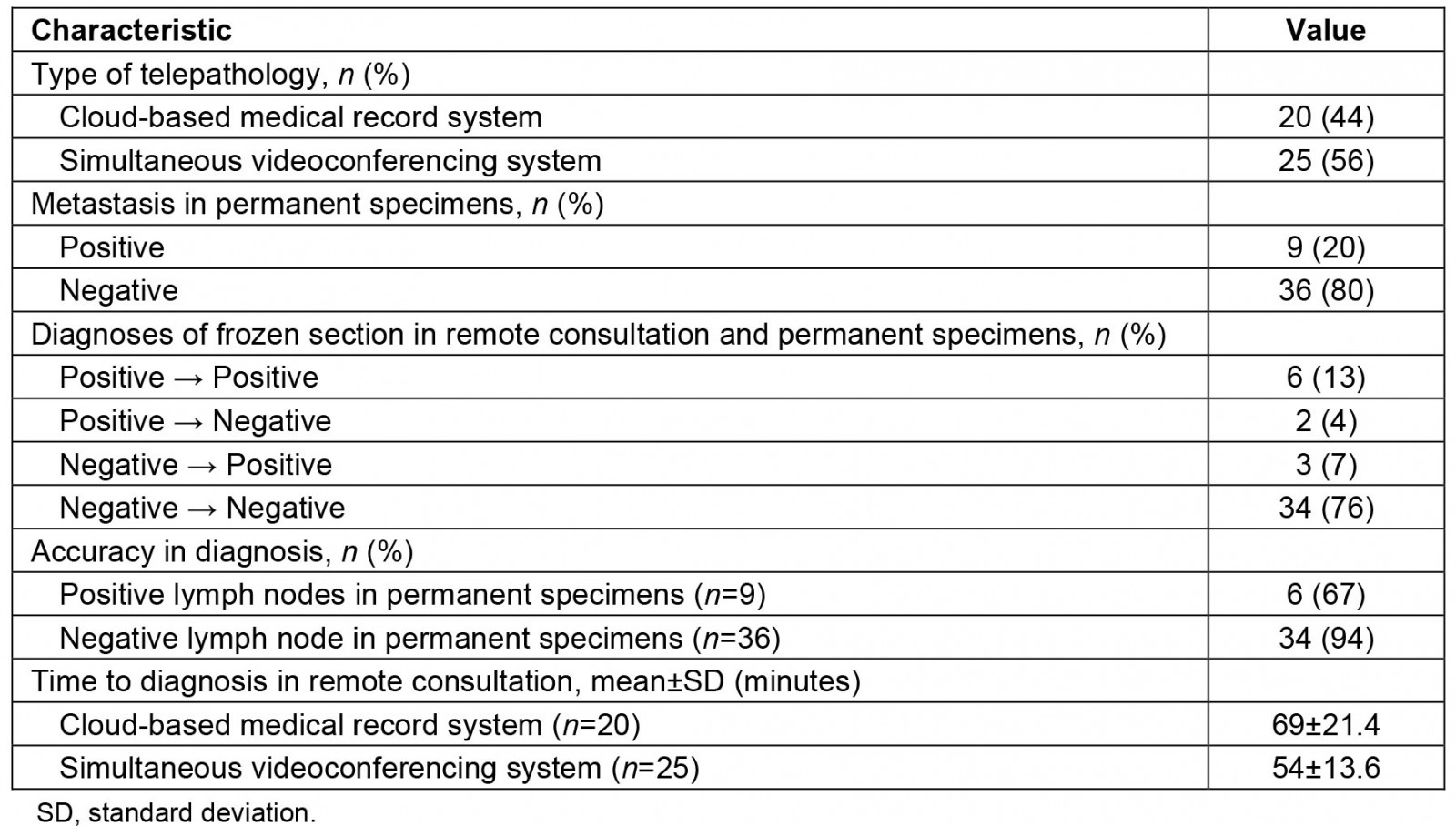

Table 3 shows the features of the sentinel lymph node biopsies including findings. In total, the surgeries of 20 patients (44%) and 25 patients (56%) involved consultation of the cloud-based medical record system and the simultaneous videoconferencing system, respectively.

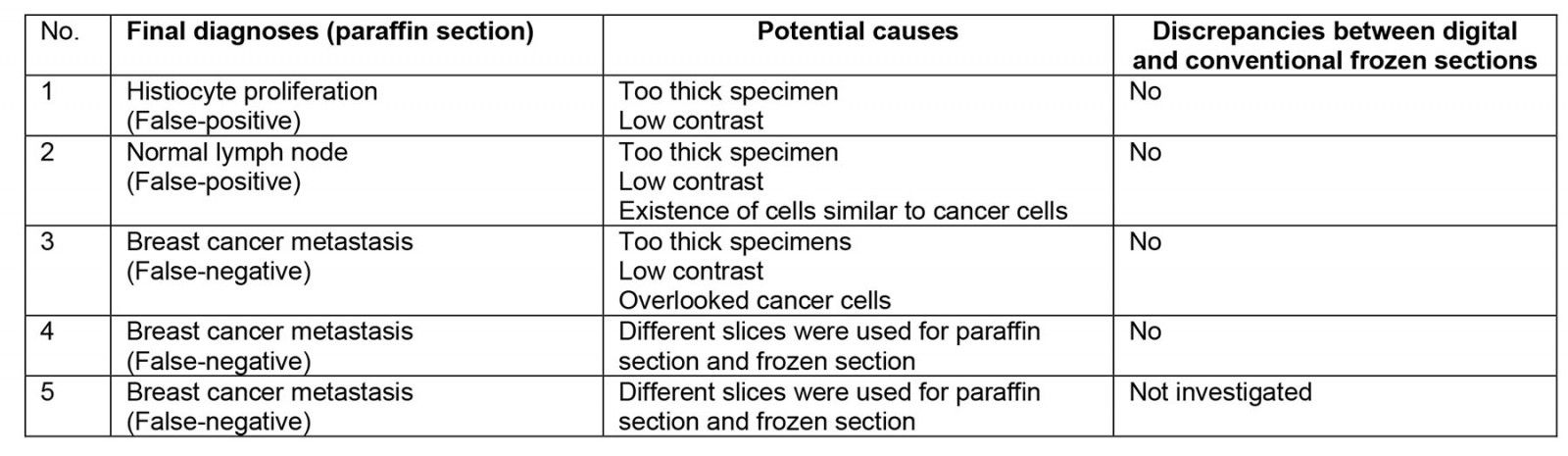

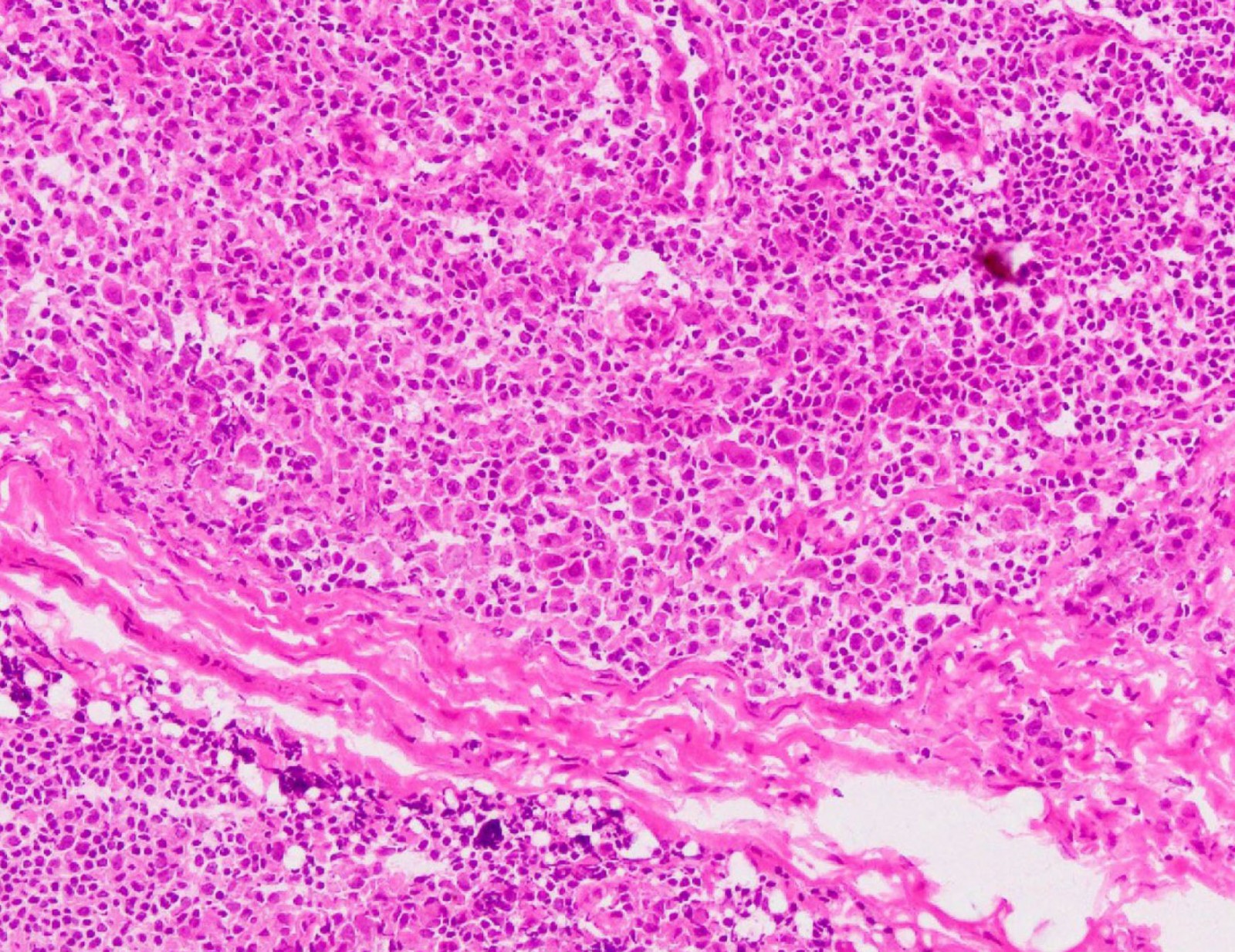

Among these, positive and negative cases in the remote consultations were 8 (18%) and 37 (82%), respectively. Compared to the permanent specimens, the overall accuracy ratio was 89% (40/45), with the positive and negative predictive values being 67% (6/9) and 94% (34/36). Supplementary table 1 shows breakdowns of cases where paraffin section and frozen section of sentinel lymph nodes differed. An illustrative example of these discrepancies is shown in Figure 1, where a false positive diagnosis occurred during a remote intraoperative frozen section consultation of a sentinel lymph node biopsy. Upon review of this case, it was determined that prominent histiocytic proliferation had been mistakenly identified as cancer cells.

We reviewed a total of four out of the five cases for which there were discrepancies between diagnosis of paraffin section and frozen section of sentinel lymph nodes. After the review, it was determined that there were no differences in diagnosis between the digital and traditional frozen sections of sentinel lymph nodes (Supplementary table 1). Furthermore, both the quality of the frozen sections and the images obtained from the monitor for the digital slides were excellent. There were no issues such as tissue wrinkles, tissue overlap, tissue folding or air entrapment in the microscopic preparation. There was no apparent difference in diagnostic accuracy between the two systems.

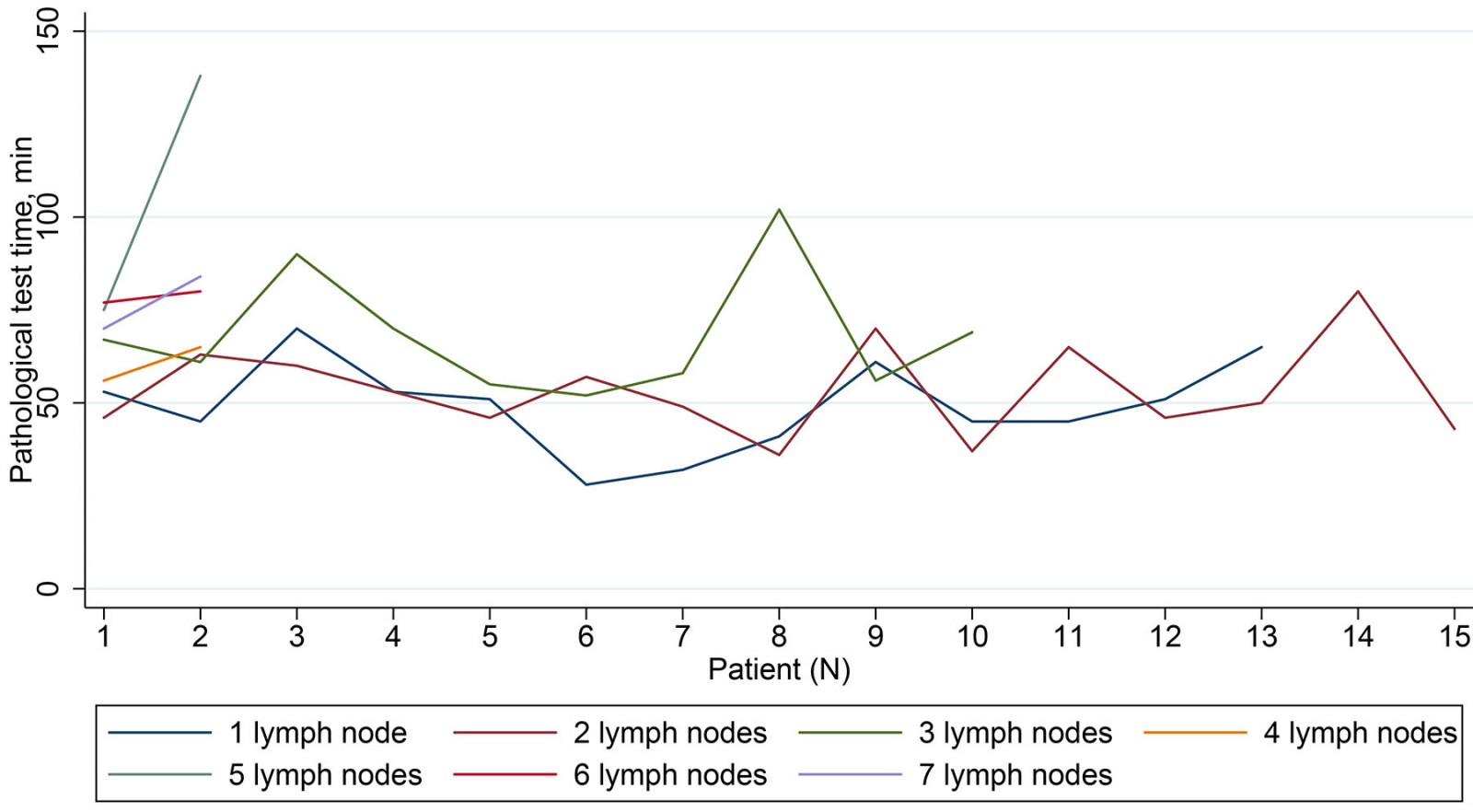

The average examination time required for a remote diagnosis of sentinel lymph node was 61 minutes (69 minutes by the cloud-based medical record system and 54 minutes by the simultaneous videoconferencing system). There was no apparent difference in the time required for remote consultation as stratified by the number of examined lymph nodes (Fig2).

Table 2: Clinical characteristics of patients (n=45)

Table 3: Characteristics related to sentinel lymph node biopsy

Figure 1: Microscopic image (hematoxylin–eosin stain) of extracted lymph node from case 1 (200× magnification).

Figure 1: Microscopic image (hematoxylin–eosin stain) of extracted lymph node from case 1 (200× magnification).

Figure 2: Time required for remote consultation as stratified by number of examined lymph nodes.

Figure 2: Time required for remote consultation as stratified by number of examined lymph nodes.

Discussion

During its initial introductory phase, an accuracy of the diagnosis using telepathology in intraoperative frozen section consultation of breast cancer sentinel lymph node biopsy in the area struck by the 2011 triple disaster was slightly inferior to the previous studies4,5. The primary reason for our findings may be attributed to our study's limited duration, focusing on the initial phase of telepathology's introduction. Notably, since the conclusion of our study, we sense that the accuracy of telepathology diagnoses seems to have improved as the hospital has conducted one of the largest volumes of breast cancer surgery in the area, while we suffer from chronic shortages of various specialists, especially pathologists, following the disaster.

The time required for telepathology was relatively long for a consultation of sentinel lymph node biopsy for intraoperative breast surgery. This may be largely due to lack of experience of telepathology and unfamiliarity with the equipment, as it was in its introductory phase. For example, a previous study reported that the average time taken to conduct an onsite sentinel lymph node biopsy was 28.15 minutes, nearly half of the time we report here15. This is concerning because increasing surgical and general anesthesiology time would harm patient outcomes. Although the time did not apparently decrease over time during the study period in our study, this is expected to improve as more experience accumulates16.

We report the use of two types of telepathology technology with comparable diagnostic accuracy. The cloud system took a longer time than the simultaneous videoconferencing system, and this may be affected by the time it takes to upload the images, and data transfer speeds. The current simultaneous videoconferencing system has the advantage in terms of speed as it is connected by the virtual private network. Further, in this study, the cloud system incurred more initial costs (mostly for the digital scanner) and running costs than the simultaneous videoconferencing system. In this sense, the simultaneous videoconferencing system may have been more advantageous than the cloud system both in terms of time and financial aspects in this small sample study.

There is a controversy about the need for rapid intraoperative diagnosis of sentinel lymph nodes for breast cancer. Some recent studies showed the feasibility of omitting axillary dissection without compromising survival rates17,18. To minimize the potential harms to patients, we need to take a cautious approach if telepathology becomes widely available.

Determining the accuracy of digital frozen sections presents a challenge due to the selection of a suitable reference standard. In this study, we chose a traditional paraffin section as the reference. However, when comparing digital frozen sections to traditional paraffin sections, it is important to consider potential confounding factors, including the quality of the system used to upload the image of the frozen section and the monitor used to read the digital images. Nevertheless, as stated in our results, no clinically significant difference in quality was observed between the digital and conventional frozen sections, which supports the validity of our methodology for comparison.

Clinical implications of the study

We believe that using telepathology in intraoperative frozen section consultation of breast cancer sentinel lymph node biopsy is acceptable. It is true that the cost of sentinel lymph node biopsy is not reimbursed by the national health insurance system if full-time pathologists are not available in institutions in Japan, whether or not the diagnosis is made using telepathology. However, sentinel lymph node biopsy is a standard procedure essential in breast cancer surgery and its omission is not realistic just because its financial costs are not reimbursed.

Further, before we implemented telepathology, we had to perform sentinel lymph node biopsy using the cytology technique, which is not a standard procedure. By introducing telepathology, a pathological diagnosis was made by experienced specialists at a relatively low cost compared to hiring a full-time specialist. Considering that rapid intraoperative diagnosis of frozen section of sentinel nodes is challenging, we consider that the diagnostic accuracy of telepathology reached a clinically acceptable level. Thus, in this respect, it is recommended to implement telepathology in intraoperative frozen section consultation of breast cancer sentinel lymph node biopsy in any institutions in similar situations.

Simultaneously, the promotion of telepathology will result in the system being adopted by a greater number of institutions and pathologists. This will standardize techniques and processes for pathology specimen preparation, thereby reducing variability in pathological diagnoses and enabling individuals in any region to receive high-quality treatment.

Limitations

This study did not systematically analyze safety issues related to an implementation of telepathology technique. However, fortunately we had not experienced severe safety issues until now. Particularly during its introductory phase, great care was taken in handling the specimens to avoid patient mix-ups, since patient information was entered manually into the system. Nonetheless, we experienced minor but non-negligible issues such as scan failure and too-thick paraffin sections. Since these issues can prolong an operation time and may negatively affect patient conditions, their occurrence should be minimized. However, we note that both the quality of the frozen sections and the images obtained from the monitor for the digital slides were excellent.

Conclusion

In the post-disaster setting of Fukushima, Japan, remote consultation for sentinel lymph node biopsy was successfully implemented with relatively high diagnostic accuracy, although the consultation time seemed to be longer than that previously reported for onsite intraoperative frozen section consultation.

Funding

No funding was received for this research.

Conflicts of interest

Akihiko Ozaki receives personal fees from MNES Inc., Kyowa Kirin Co., Ltd. and Taiho Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., outside the submitted work. Tetsuya Tanimoto receives personal fees from MNES and Bionics Co., outside the submitted work. Kouki Inai, Yasuteru Shimamura and Naoyuki Kitamura are staff members of MNES. No other authors report conflicts of interest.

References

Supplementary material is available on the live site https://www.rrh.org.au/journal/article/8496/#supplementary

You might also be interested in:

2014 - Mental health services for Nunavut children and youth: evaluating a telepsychiatry pilot project

2012 - Physician in practice clinic: educating GPs in endocrinology through specialist-outreach