Introduction

Chronic household food insecurity (HFI) and lack of food availability and accessibility in isolated communities are longstanding public health crises. HFI, which describes inadequate food access, availability, and utilization due to insufficient financial resources1, is an important social determinant of health, associated with a number of adverse health outcomes, even at marginal levels2. Other aspects of food security, such as the availability of and physical access to healthy foods, are uniquely challenging to achieve in remote regions3.

Though this review focuses on all community members in remote communities, it is noteworthy that HFI prevalence is higher in some population groups, including those who identify as Indigenous (see Box 1)1. Remote circumpolar communities include people of all demographics, but many were created or populated as a result of the forced relocation of Indigenous Peoples4,5. Colonial, political, and environmental forces have contributed to deep inequities in food security. For example, the 2007–2008 Inuit Health Survey within Canada found that 69% of Inuit adults living in remote northern regions were food insecure compared to the national average of 9.2%6.

Food systems in remote circumpolar communities consist of a combination of purchased market foods and traditional foods, harvested and shared locally and sometimes regionally4,5. ‘Traditional food’ is the term more commonly used by First Nations and Métis communities, while ‘country food’ is generally the preferred term of Inuit. In this review, we use the term ‘traditional food’ to refer to traditional/country foods that are locally harvested, unless the specific study or citation being referred to exclusively uses the term ‘country food’. Deep inequities have resulted in elevated levels of food insecurity in remote and Indigenous communities7. Further degradation of food systems has resulted due to nutritional and dietary shifts away from traditional food to highly processed store-bought foods, and have continued to perpetuate food insecurity8,9. Market food is often imported on airfreights that are vulnerable to the impact of increasing fuel costs and unpredictable weather10.

The increasing costs of supplies for fishing and hunting have led to difficulties in procuring traditional foods, reducing the supply of nutritious foods in some communities as well as the ability to share this food across family and social networks11-13. These challenges are evidenced by a decrease in harvesting activities within the past two decades by working-age Indigenous adults in remote communities within Canada14. This decrease has been partially attributed to climate change, which has altered access to traditional harvesting areas, safety for harvesters while on the land, migration patterns of animals, harvest size, and contaminant levels in traditional foods14,15.

A variety of initiatives and programs have been designed to improve food security in remote communities. Many of these initiatives are government-led, which continues to perpetuate the negative history of Indigenous–governmental relationships16,17. The narrow scope of many of these initiatives may not address the systemic issues affecting food security16. As a result, researchers, including Indigenous scholars, have argued for a move from a discussion of food security to a dialogue focused on food sovereignty, and localized community-based initiatives to mitigate food insecurity18,19.

‘Food sovereignty’ is a framework for transforming food and agriculture to ensure food security and strengthen self-sufficiency, social equity, and self-determination20. This emphasizes the need to place more control into the hands of those who have been systematically excluded from the formulation of food policy21. Beyond the components of food security, food sovereignty focuses on community involvement in food systems, and, in Indigenous populations, looks at the availability of culturally appropriate foods22. As such, food sovereignty can assist with creating localized food systems and tackling the food insecurity crisis that remote Indigenous populations face within Canada23,24.

This scoping review synthesizes initiatives addressing, and modifiable factors associated with, food security in remote and isolated communities across circumpolar countries and other affluent countries with similar colonial histories and remote communities. The primary objectives of this review were to inform policy development by (1) summarizing primary research and grey literature on food security initiatives and exposure factors in remote and isolated communities across multiple countries and (2) identifying research gaps and future areas of inquiry.

Box 1: Groups constituting Indigenous Peoples4.

Methods

A scoping review method was selected to determine the breadth of food security initiatives and outcomes in remote and isolated communities. This review was guided by the process outlined by Arksey and O’Malley25 and the PRISMA reporting guidelines for scoping reviews26. The review protocol was registered to Open Science Framework prior to data collection27.

Eligibility criteria

This review aims to inform policy development within northern Canada. Due to the small number of studies evaluating food security initiatives in remote communities within Canada, other jurisdictions facing similar challenges were included. These include the US, Finland, Sweden, Norway, Greenland, and Russia, all of which are circumpolar countries with remote and isolated communities. Additionally, studies from Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand, two affluent countries with similar Anglo-European colonial histories with primarily Indigenous remote communities, were included. Though these countries are higher income on average, conditions within these countries can be unequal.

This review focused on communities classified as remote and/or isolated. The Canadian Public Health Working Group on Remote and Isolated Communities defines a community as remote or isolated if it is more than 350 km from the closest service centre that has all-weather, year-round land or water access28. For the purposes of this review, included communities were classified by their government and/or self-defined as remote or isolated, and/or do not have year-round road access.

To fulfill the inclusion criteria, the study must have included a quantitative measurement of a food security or sovereignty outcome (see Supplementary table 1). Qualitative outcomes were not included within this review, though are recommended for a future companion review, in the interest of limiting this review’s length and scope. In addition to validated scales, outcomes may have included self-reported experiences or perceptions of food security, food purchasing practices, food costs, traditional food consumption or access, and diet diversity. Participant satisfaction towards the initiative/exposure factor was also included to quantify the acceptability of programs. Toxicological and food contamination studies were excluded if there was no food security or sovereignty outcome. This review includes studies evaluating both initiatives and exposure factors that could be modified through local, regional, or national policy:

- Initiatives, or interventions, were designed by either the researchers or another organization and applied to address food security or sovereignty.

- Exposure factors are naturally determined (eg in observational studies) factors, which were included if they could be modified or addressed through local, regional, or national policy. Examples of these factors might include education level, household income, or the number of grocery stores in the community. Some examples of exposure factors that cannot be modified through policy that were excluded in this review are sex, gender, age, and race.

Studies evaluating the effects of climate change and/or the global agricultural supply chain were excluded.

Search strategy

The search strategy (Supplementary table 2) underwent Peer Review Electronic Search Strategy (PRESS)29 and included health databases Ovid MEDLI(R), PsycINFO, and Embase, SCOPUS, food science database Food Science and Technology Abstracts, and economics database EconLit. The review included studies published in English and French from January 1997, after a definition of food security was established and universally agreed upon30,31, to June 2022. A grey literature search was conducted according to the methods described by Godin et al32 (Supplementary table 2). Articles were screened from the first 10 pages of Google results and targeted websites, and were also identified from reference lists of reviews and published works of identified experts.

Study selection

Identified citations were uploaded into DistillerSRV2.43.0 and screened using pre-piloted forms (Supplementary table 1). Titles and abstracts were screened by two independent reviewers. An article was included if one screener determined that it fit the inclusion criteria, and excluded if both reviewers determined that it did not fit the inclusion criteria. At the full-text stage, reviewers reached consensus for study inclusion and exclusion at the answer level.

Data extraction

Data extraction followed the process outlined by Arksey and O’Malley25, using PRISMA guidelines for scoping reviews26. Two reviewers independently extracted data using a pre-piloted form. Inconsistencies in extracted data were resolved through consensus. Study risk of bias was assessed as part of data extraction. Though risk of bias is not a requirement for scoping reviews, the authors included study quality appraisal to provide additional context for policymakers when reviewing the evidence. Risk of bias was assessed using either Risk of Bias in non-randomized Intervention Studies (ROBINS-I)33, Risk of Bias 2 for randomized controlled trials34, or Risk of Bias in non-randomized exposure studies35 tools, based on study design. Risk of bias was not assessed for studies with modeled outcomes.

Stakeholder consultation

In February 2022, the authors were invited to present the results of this scoping review to an expert panel in support of a meeting discussing northern food systems. The panel consists of community members, academics, and other experts in the field of food security within northern Canada, and consists of both a majority of Indigenous Peoples and a majority of people living in northern communities. Panel members provided verbal feedback regarding review results, which has been incorporated throughout.

Results

Literature search

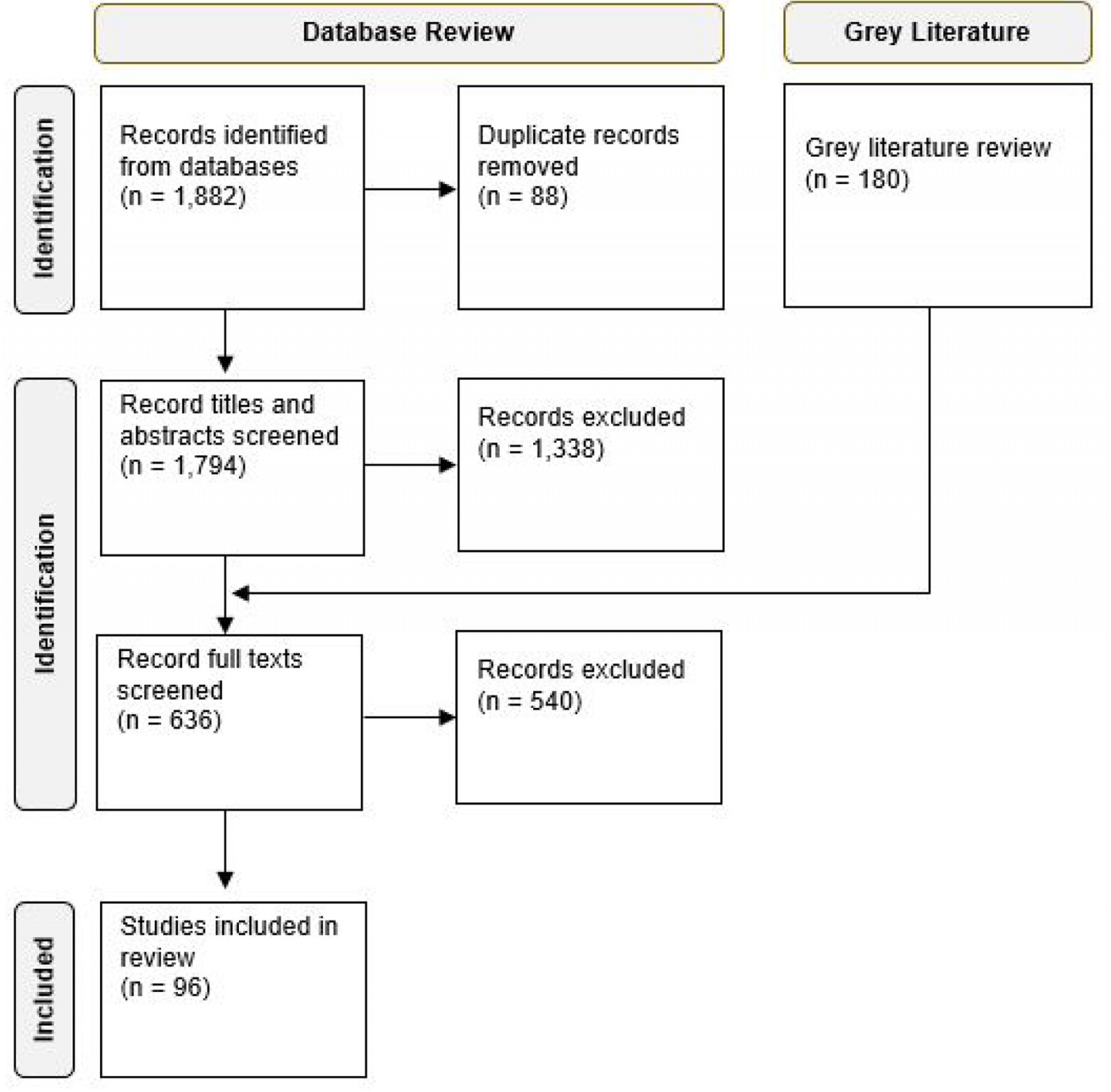

The database review identified 1882 studies from the indexed search and 180 studies in the grey literature, of which 96 were included in this review (Fig1).

Figure 1: PRISMA diagram for scoping review.

Figure 1: PRISMA diagram for scoping review.

Countries of study

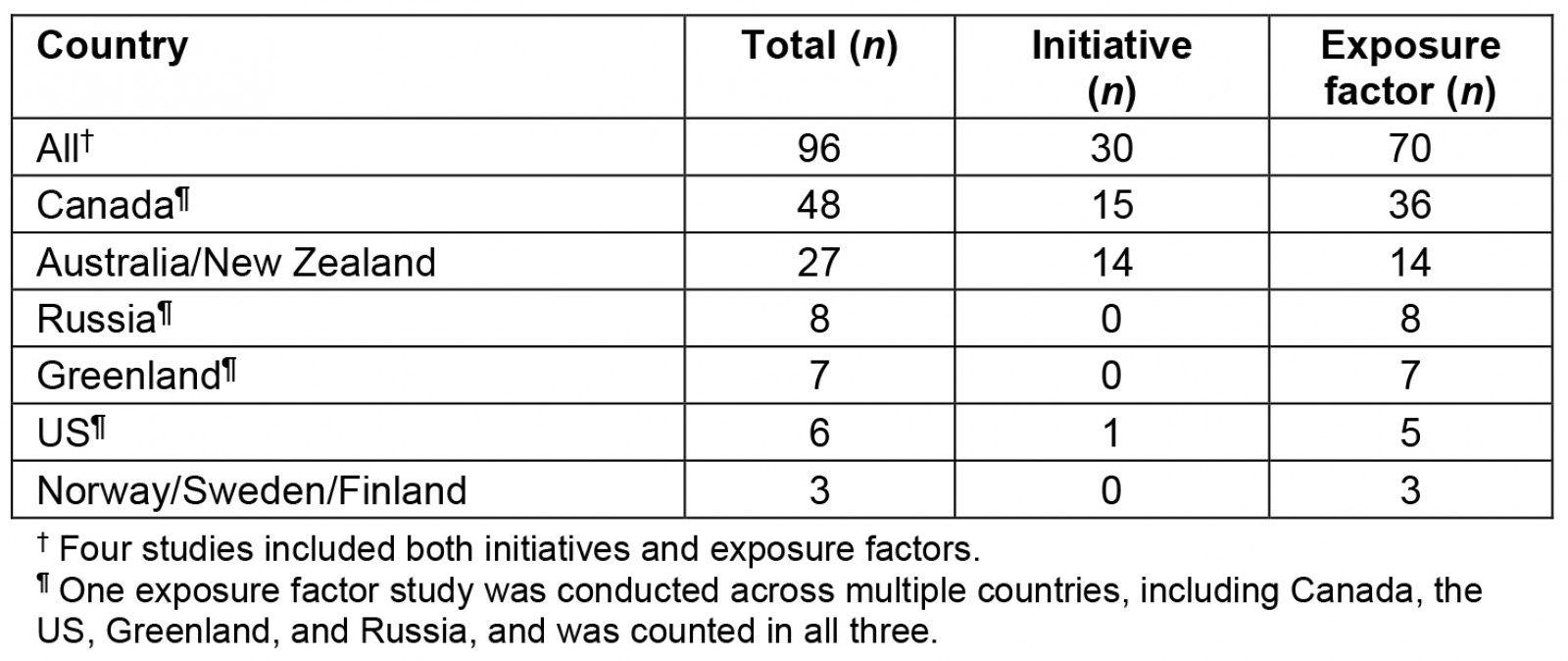

The majority of the studies included in this review were conducted within Canada (50%) and Australia (28%) (Table 1). No initiative studies conducted in Russia, Greenland, Norway, Finland, or Sweden fulfilled the inclusion criteria.

Table 1: Countries of study included in scoping review

Outcomes

A variety of quantitative food security outcomes were identified, including HFI, food or nutrient intake, food sales, food costs/spending, dietary quality, traditional food yields, and food sharing. No quantitative measure of food sovereignty was identified, and no studies quantitatively measured participant satisfaction.

Initiatives

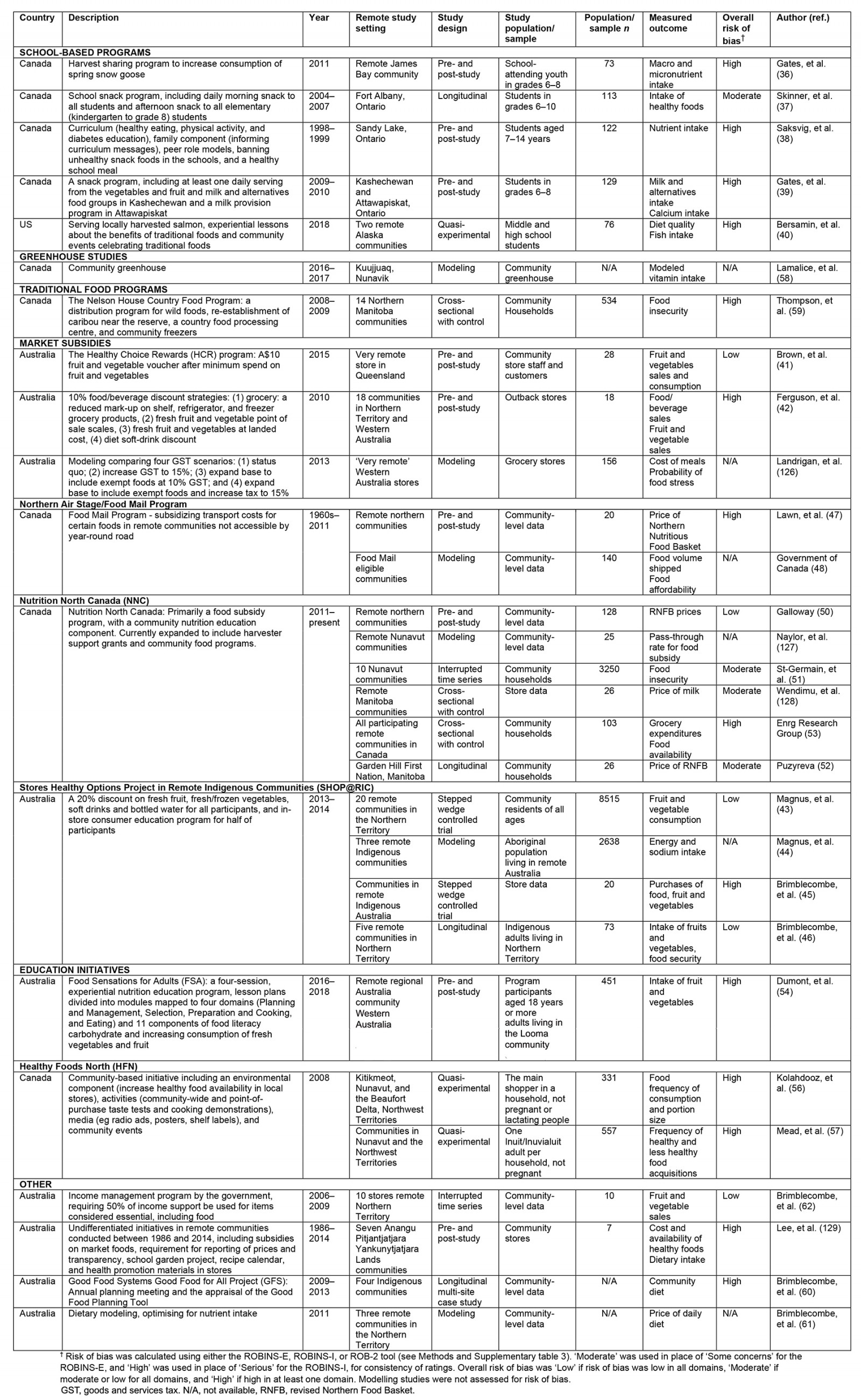

Thirty studies evaluating 20 different initiatives were included (Table 2). The majority of these were either pre and post (n=9) or modeling (n=6) studies. Most included studies had high risk of bias (Supplementary table 3), primarily due to confounding or outcome measurement. However, four of the market subsidy initiatives had low risk of bias for all domains.

School-based initiatives: Five school-based initiatives were evaluated in the included studies; four in Canada36-39 and one in the US40. All five included a food component, such as a school snack37-39, or local traditional foods36,40. The implementation of all five programs was associated with significant positive changes in food security outcomes. These included improved diet quality36,40 and nutrient intake38,39, though overall risk of bias in these studies was high due to factors outcome measurement, missing data, and confounding. The changes observed in an Ontario snack program were not sustained over the long term due to insufficient funding, and lack of infrastructure and storage39. A study evaluating a snack program in northern Ontario showed increased healthy food intake, and had moderate risk of bias due to confounding, which may be a result of the small sample size37. Though all of these programs were associated with improvements to food security outcomes, improvements did not always reach dietary adequacy recommendations36,37.

Market subsidies: Six different market subsidy programs were evaluated across 15 studies. Both a food voucher program and a 10% grocery discount program in Australia showed no association with fruit and vegetable sales41,42. The low impact of these programs was attributed to factors including store staffing challenges and limited infrastructure in a study with low risk of bias41, as well as the small discount size in a study with high risk of bias42. A 20% discount, with an additional in-store educational component, was applied during the SHOP@RIC intervention in Australia43-46. This level of discount was associated with increases in fruit and vegetable purchasing in two studies, both of which had low risk of bias43,45, though no significant change in fruit and vegetable consumption or diet quality44,46. The majority of the change in purchasing was associated with the discount program, rather than the education component43.

In Canada, the implementation of the Food Mail Program, a national food shipping subsidy, was associated with lower food costs and higher food shipment volumes47,48, though was underused due to challenges related to accessibility and visibility49. The program was replaced with Nutrition North Canada (NNC) in 2011, a tiered subsidy program based on level of remoteness49. The implementation of NNC was associated with a decrease in food prices, but those prices have remained generally stable since the program’s inception in 2011, including in one study with low risk of bias50-53. Additionally, HFI levels in NNC-eligible communities increased after implementation of the program51. The majority of the studies evaluating the NNC program had moderate risk of bias, primarily due to lack of controlling for confounders or the possibility of post-exposure interventions.

Education initiatives: Several of the interventions evaluated as part of this study (eg NNC, SHOP@RIC) included an education component, though the impact of this component was either minimal, in the case of SHOP@RIC, or not evaluated independently, in the case of NNC. Education components, including lessons on healthy eating38 and the benefits of traditional foods40 were also included as part of two of the school-based interventions, though not differentiated during analysis.

In Australia, the Food Sensations for Adults program, which included lessons on meal planning, cooking, and food literacy, was associated with a significant increase in fruit and vegetable intake54. A second Australian initiative involved healthy eating and physical activity sessions, targeted at diabetic Indigenous adults, showed no significant changes in dietary habits55. In Canada, the Healthy Foods North (HFN) program was created in partnership with six northern communities, and included both store-based and community-based educational events56. Significant changes were observed in the intervention group, including increased consumption of promoted healthy foods56 and increased consumption of healthy foods from baseline57. All education initiative evaluations had high risk of bias, primarily due to lack of controlling for confounders, which may not be possible due to small sample size, and possible bias by evaluators due to their knowledge of the participant’s participation.

Greenhouses, traditional food programs, and other: Several initiative types were evaluated in only one article. A greenhouse in Kuujjuaq, Nunavik had a modeled output that could meet the nutrient requirements for between 1 month and 1 year, depending on the nutrient58.

The Nelson House Country Food Program is a Manitoba traditional food program that includes food distribution, processing, and freezer storage, and the re-establishment of a local caribou population59. The community had significantly lower rates of HFI than other similarly sized remote communities in Manitoba, and community members attributed the lower rates to the program59. The evaluation of this program had high risk of bias, due to the presence of other post-exposure initiatives in the comparison communities.

The Good Food Systems Good Food for All Project (GFS) was a community-led program in four remote Australian communities involving annual planning meetings and evaluation of traditional food production, market food business, and community services60. The implementation of this program was not associated with a change in food sales, though authors noted that the program was intended to affect a broader set of outcomes that were not evaluated, including food quality and access60. This study was at low risk of bias for all domains with the exception of confounding, due to the lack of controlling level of remoteness or price differences between communities. Other articles evaluated Australian programs, including dietary modeling, and income supplementation61,62.

Exposure factors

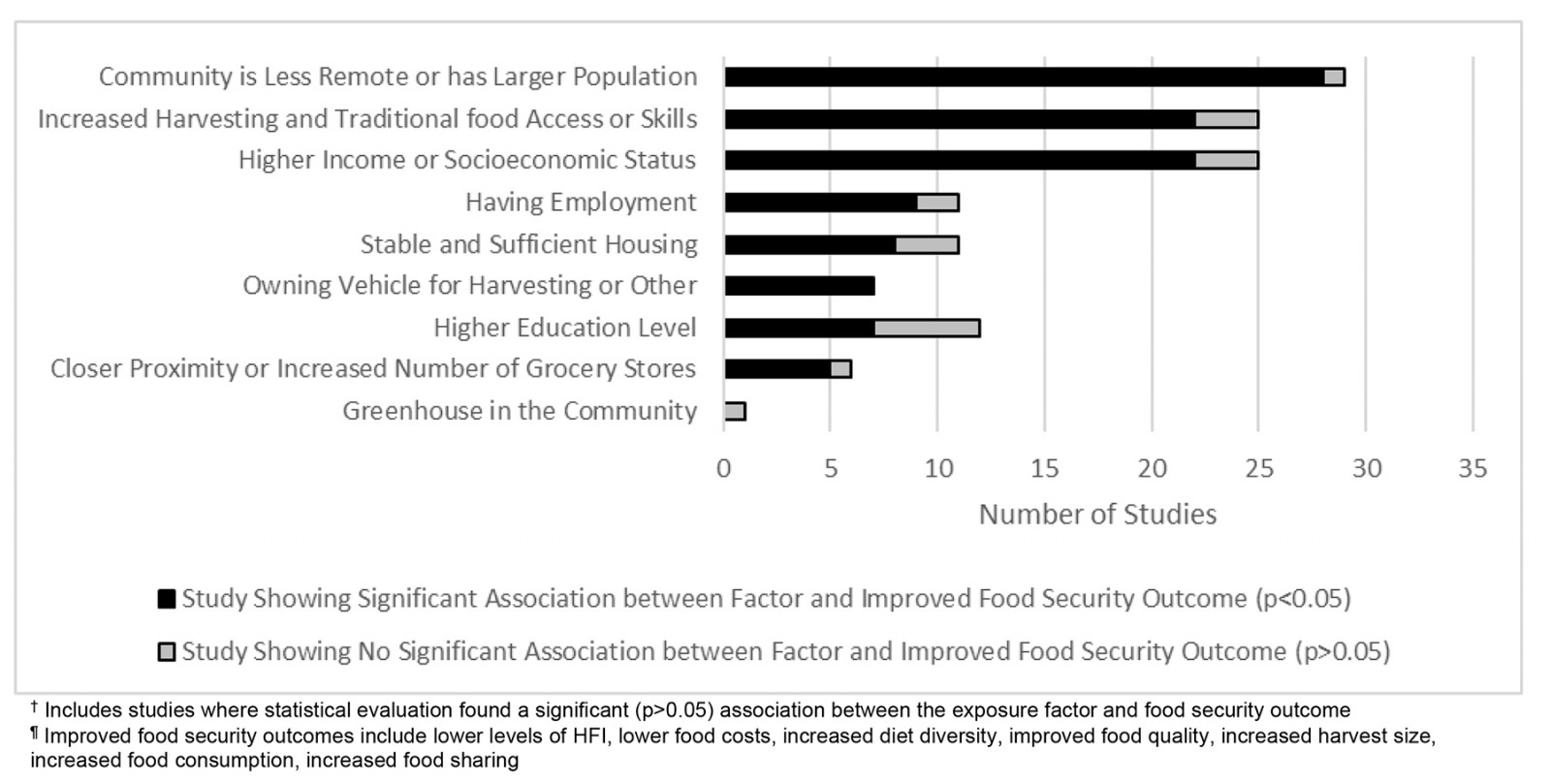

Exposure factors were divided into nine categories and compared to food security outcomes (Fig2). Half of the studies (n=35/70) evaluated more than one exposure factor and were therefore included in the summary figure multiple times. Four studies included both an initiative and exposure factor and have been included in both results sections.

Remoteness and community size: Remoteness and community size were significantly associated with food security outcomes in 28/29 studies (Fig2). Remoteness was categorized differently depending on the jurisdiction or research question, and therefore level of remoteness cannot be compared between studies. Remote communities located in Canada, Australia, Scandinavia, Greenland, and Russia had higher levels of food insecurity, higher food costs, and lower food availability and quality than major cities63-77. Studies from both Canada and Greenland found that larger communities had lower levels of HFI than smaller remote communities in the same regions78-80; however, two studies located in Canada found no relationship between community size and food security or cost81,82. Food security associations related to remoteness and community size may not apply to traditional food harvesting patterns, as one Russian study found that remote communities had higher traditional harvest yields than rural towns83.

Figure 2: Summary of exposure factors associated† with improved¶ food security outcomes.

Figure 2: Summary of exposure factors associated† with improved¶ food security outcomes.

Harvesting and traditional food: Traditional food intake and availability were associated with food security outcomes in 7/10 studies. Half of these studies evaluated dietary intake, reporting that community members in remote communities within Canada and Greenland who consumed more traditional foods had higher intakes of macronutrients, particularly protein36,84-86, and micronutrients, such as zinc36,85,87. Greater traditional food availability was associated with lower HFI rates in studies located in the USA and Canada88,89. However, eating traditional food at more than 50% of meals was not associated with HFI in two studies located in Canada90,91. This lack of association was attributed to the nutritional transition from traditional food to market foods in the younger generations90.

Harvesting factors, such as having a harvester in the household, harvesting skills, harvest sharing, and harvest diversity and size were correlated with food security in 14/18 studies. The most common outcome measured in these studies was out-degree food sharing (44%), which measures the number of food sharers, while in-degree food sharing measures the number of food recipients. Out-degree sharing was higher in households with larger harvests92 or a harvester in the household93, greater harvest diversity and traditional harvesting practices94,95, and those reporting stronger hunter skills96,97. Unlike out-degree sharing, in-degree sharing, which measures receiving shared foods, was not correlated with harvest size in one study of a remote Inuit community98. Having a harvester in the household was correlated with lower rates of HFI99-101 and higher traditional food consumption102. Learning subsistence skills as a child was associated with larger harvests103 and participation in harvesting was associated with higher traditional food consumption104,105.

Income/socioeconomic status: In most studies assessing the relationship between income and socioeconomic status (n=23/26), higher income households had lower rates of HFI. Two studies located in Canada each found that HFI levels were higher when household income levels were below the national median78 or below C$20,000 (A$21,900)81. Similar trends were observed in Greenland, where houses with the lowest asset scores were more likely to be food insecure than houses with the highest scores80,106. Studies from Canada, Australia, and Greenland found that having lower income or being on income assistance was associated with higher rates of HFI90,91,106-108, fewer hunters in the household109, higher frequency of traditional food consumption102, reduced dietary quality and diversity (based on Australian recommendations for children <2 years old)110-115, and receiving more shared food98,116.

Employment: Employment status was significantly associated with food security outcomes in the majority (n=11/13) of included studies. In Canada and Greenland, those without jobs were more likely to be food insecure78,90,91,106,108,117, have a less diverse diet118, and share foods93, though food sharing was more strongly correlated with harvesting-related factors, such as having a hunter in the household, than with employment status93. In studies located in both Canada and Australia, employment status was not associated with other outcomes including the number of hunters per household109, and the percentage expenditure on discretionary food119. One study located in Canada found that those in desirable workplaces, including those with better pay, benefits, and hours, had higher levels of food sharing than those in less desirable workplaces98.

Housing: Housing status, including household size, crowding, and repair needs, was associated with food security outcomes in the majority (n=9/12) of studies. Four studies located within Canada found that HFI levels were higher in homes in need of major repairs or characterized as public housing81,90,99, or in overcrowded homes (more than one person per room)78,81. In Canada and Australia, larger households were more likely to be food insecure, and less likely to meet adequate meal frequency110,116,120. Household size was also not significantly correlated with food sharing in both a Canadian116 and Russian96 study. In Canada, housing status correlated with income, and the association between food security outcomes with income, was stronger than the association with housing status98,116.

Vehicle ownership and access: Ownership or access to vehicles for harvesting or other uses was significantly associated with food security outcomes in all seven included studies. Though vehicles may not be necessary for in-community transportation, they can be important harvesting tools92. Owning a vehicle for harvesting was associated with lower HFI rates116,120 and greater out-degree food sharing92,98,121 within Canadian and Russian communities. Similarly for market foods, Australian households with more transport modes were more likely to achieve adequate vegetable consumption122, and Manitoba communities with public transport had lower HFI rates89. Though vehicle ownership and access allows for greater food access, this variable was not always retained in models that included income116.

Education level: The majority (n=9/14) of the articles evaluating education level as an exposure factor associated with food security used a threshold of having completed high school/secondary school. Six of seven studies conducted in Canada and Greenland showed a relationship between higher education levels and food security78,81,90,91,99,106, while three, conducted in Canada and Australia, did not116,120,123. Other outcomes associated with a higher education level included lower spending on, and consumption of, traditional foods, and higher spending on fruits and vegetables102,124. One of these studies found that, though the correlation between education and HFI was not significant, higher levels of education were associated with higher income levels, which were significantly associated with HFI120.

Stores: Six studies, primarily from Australia (67%) evaluated store factors, such as the number of stores in a community, the distance to a store, and the frequency of food delivery. These studies found that communities with more stores, or where community members felt the number of stores was adequate, were more likely to be food secure89 and had greater diet diversity (total number of different items eaten)118 and vegetable consumption122. However, these studies did not control for population size, a possible factor affecting the number of community stores. One study conducted in Australia found that more food was purchased immediately following loading days125; however, another Australian study did not find that an association between food delivery frequency and diet quality119.

Number of greenhouses: One study found no significant association between the number of greenhouses in remote Manitoba communities and HFI, though greenhouses were found to increase the length of the growing season in the community59.

Table 2: Studies evaluating food security and sovereignty initiatives in remote and isolated regions36-48,50-62,126-129

Discussion

This scoping review identified studies conducted in remote and isolated communities, which was made challenging by the use of different terminology and standards in different jurisdictions. For instance, Australia classifies communities based on road distance to service centres in towns of different sizes130, while the other jurisdictions in this review do not have standardized classification systems. Therefore, this study’s authors used other indicators, including access or self-describing as remote. These factors also differed between jurisdictions, resulting in the underrepresentation of some countries that have year-round rail and road networks, such as those in Scandinavia. A standard remoteness indicator could facilitate future evaluation studies and help to identify high priority communities for initiatives.

Most of the studies included in this review found significant associations between food security outcomes and exposure factors including level of remoteness, income, housing, education, employment, vehicle ownership, and traditional food and harvesting practices. These factors can be interrelated, particularly with income. For instance, in Australia, increased remoteness was associated with decreased income and increased income disparity between Indigenous groups and non-Indigenous groups131. Studies within both Canada and Greenland showed that though education level and vehicle ownership were significantly associated with food security, these outcomes did not retain significance in models where income was included80,116. Though not evaluated quantitatively, the general conclusions of studies located in Canada and Greenland stressed the importance of sufficient income for both market and traditional food acquisition109,116 and noted socioeconomic status is a significant determinant of food security80,106.

The results of this scoping review have identified significant data gaps in food security research in remote regions. In particular, a variety of initiatives being applied in these settings, such as greenhouses, community freezers, and traditional food programs, have not been evaluated132. A 2019 study documented 36 community gardens and 17 greenhouses in remote northern Canada, though very few quantitative evaluations have been published58,133,134. In some cases, large-scale national programs lack evaluation, particularly for community-led initiatives and for food sovereignty outcomes. For instance, the effect of the Harvesters Support Grant, a funding program for traditional food harvesting established by NNC in Canada in 2019, has not been evaluated135.

The small community size and nature of these initiatives also results in challenges in interpreting the impact/effect size of initiatives due to risk of bias. The majority of initiative studies had high risk of bias in at least one domain. Challenges including small community size, where confounders cannot be adjusted for in statistical analysis, and the inability to blind participants to programs such as school snacks or education initiatives, results in possible bias in outcome measurement. Several market subsidy studies evaluating Australian programs41,43,45 and NNC50 had low risk of bias in all domains. Despite changes in food pricing and sales associated with these initiatives, authors stressed the limited impact of these programs in isolation41,43,45. The impact of NNC, in particular, on HFI has plateaued since its inception in 2011, and the program has been criticized due to its lack of transparency and community control50,136.

The majority (n=28/30) of the initiative studies measured a single component of food security, such as diet quality, food cost, or spending on food. Inconsistency in outcomes leads to challenges when comparing the initiative effectiveness for decision-making. Outcome selection is critical for ensuring that the most important success indicators, particularly those that are important to the impacted communities, are being measured. For instance, authors of the Australian GFS study noted that outcomes such as food quality and access may have been impacted but were not measured60. Outcome selection may also result in the misclassification of a program as successful when the full picture is more complicated. For example, the NNC program has primarily been evaluated based on food cost and subsidy pass-through rates, both of which improved since program implementation. However, HFI levels in eligible communities increased during the same period51.

Despite the small number of evaluations and the inconsistency in measured outcomes, several trends were observed in terms of recommendations for initiatives in remote communities. The importance of traditional foods for First Nations, Métis, and Inuit people was noted in both initiative and exposure factor studies36,40,56-59. Traditional food consumption is an important determinant of food security in remote communities, both due to the nutrient density of these foods and the importance of these foods in achieving food sovereignty85-87. Programs that increased traditional food access and affordability help to create sustainable livelihoods, in communities that otherwise rely on market foods59.

The importance of community engagement and community-led initiatives was stressed in 20% of initiative studies. Culturally adapted, including the application of Indigenous methodologies selected by the impacted community, and collaborative implementation may result in faster implementation and longer program sustainability, and may reduce health risk36,38,40,56,60. Three studies also noted the integral role of local champions or coordinators37-39. Strong community partnerships allow for the integration of local knowledge, and ensure that initiatives are both addressing the needs identified by, and evaluating outcomes relevant to, the community24.

Limitations

Due to the small number of studies, and the diversity of outcomes, direct comparison of the impact of these initiatives is neither feasible nor desirable. HFI was measured in only 19% of the included studies and most studies measured other outcomes, such as food cost, dietary changes, nutrient intake, and food sharing. These outcomes represent individual components rather than a full picture and may not measure the full impact of a program51,60.

Due to limitations in size, this study did not include qualitative outcomes. Qualitative data can provide essential information about the acceptability, feasibility, and effectiveness of initiatives, and are often the only data available in the evaluation of initiatives in remote communities. The authors recommend conducting a companion review summarizing qualitative results, which will provide policymakers with important contextual information and evaluation data.

The study settings described in included studies vary significantly, in terms of factors such as culture, traditional food harvesting, and environmental constraints. Though multiple jurisdictions were included to provide broad observations about remote settings, some of the observed differences between studies may result from these community differences.

Conclusion

Remote communities are particularly vulnerable to food insecurity, and lack of access and availability of healthy foods, compounded by factors including income, housing, education, transportation, and community infrastructure. These factors are often interrelated and can be challenging to differentiate for program development. Additionally, these regions often rely on the harvesting of traditional foods for subsistence, health, and cultural wellbeing. Traditional food harvesting can be an important determinant of food security. The studies included in this review stressed the importance of harvesting accessibility and access to traditional foods.

Though only a small number of initiatives in these regions have been evaluated using quantitative outcomes, broader trends were still observed. Variability in measured outcomes results in an incomplete picture of program impact. Initiatives, including greenhouses, freezers, school programs, and harvesting and traditional food programs, are being implemented across remote areas, but with minimal evaluation. It is recommended that future evaluations consider outcomes identified by the impacted community, or multiple factors contributing to food security, for a deeper understand of program effectiveness. Studies evaluating community-led initiatives noted that strong community partnerships resulted in faster implementation and longer program stability. This is particularly important when working with the culturally and geographically diverse groups living in remote areas. Despite the implementation of multiple initiatives throughout remote communities, the cost of a healthy diet remained high, as do levels of HFI. Further work is required to improve food security in remote regions.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Jason Pagaduan and Eric Vallieres for their support during article screening, and Alexandra Zuckerman for providing Distiller support. Thank you to Swati Swood and Lisa Glandon at the Health Library for their work putting together the search strings and grey literature strategy. The authors also wish to thank the 13 members of the HFI Guideline Panel for their valuable feedback in February 2023, which informed the interpretation of results in this review.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

Supplementary material is available on the live site https://www.rrh.org.au/journal/article/8627/#supplementary

You might also be interested in:

2019 - Partnership integration for rural health resource access

2010 - Meeting the needs of Nunavut families: a community-based midwifery education program