Introduction

Many countries face the question of how to provide equitable health care to rural and remote populations. Japan is no different and presents an interesting case as a country recognised for its high-achieving health system, universal health coverage and the world’s highest life expectancy1. Nonetheless, Japan now faces challenges spanning population demographics and distribution, increasing healthcare costs2, physician maldistribution and an entrenched workforce and training culture3. Japan comprises nearly 7000 small islands and a population of over 100 million people. Approximately 10% live in rural and remote areas (mountains, small islands and peninsulas)4. The population is the oldest in the world and nearly 50% of rural and remote populations are considered ‘elderly’4. Ageing populations introduce changes in disease burden, which are more prevalent in rural and remote areas of Japan2. Concurrently, the total population of Japan is declining, presenting new challenges around a possible future national oversupply of physicians5. This is further complicated by globally familiar realities of medical workforce maldistribution6,7, with physicians gravitating toward urban areas and choosing specialties that are more commonly practised in cities5,8. Physician maldistribution in Japan has been a concern since the 1950s8.

In Japan, the boundary between primary or secondary care and clinic or hospital care has been unclear due to several historical factors: the tradition and culture of the physician recruitment and distribution system (Ikyoku) and its historical links to (organ-based) specialist training3, the lack of a compulsory ‘gatekeeper’ referral pathway from primary to specialist care2, and a lack of formal recognition of primary care as a specialty medical workforce. Most primary care in Japan is provided by specialty physicians in private clinic and/or hospital settings9. One-third of specialists also function as generalists3 and most commonly in rural settings2. In 2018 the Japanese government formally recognised GPs as the 19th medical specialty with a new certified training system. This is one strategy to address increasing health system costs and to provide quality primary care10 to an ageing population. However, this reform presents new challenges, including efforts to recruit medical graduates into the GP pathway (only 184 enrolled in 2018 out of 8410 specialty enrollments and 250 out of 9448 by 2022)11. These challenges are exacerbated by a resistance to ‘Western style’ primary care models by other specialties3 and a need to promote primary practice to the broader Japanese population10.

The specialty recognition of general practice complements earlier reforms by Japanese governments. In the 1970s and 80s, the national government established a ‘one medical school in each prefecture’ policy, doubling the number of medical schools across Japan4. Jichi Medical University was established in 1972 as a medical school solely providing rural physician graduates4. In 2009 a rural quota, Chiikiwaku, was introduced to most medical schools4. Chiikiwaku medical entrants receive a scholarship from their home prefecture, usually with an obligation to return to rural practice4. Despite these reforms, there is wide recognition that more must be done4,5,12, including the need for medical generalists trained specifically for rural practice8.

It is with this background and context that a Japanese organisation, GENEPRO, established the Rural Generalist Program Japan (RGPJ) in 2017 to support medical training in rural and remote areas13. The RGPJ is a small, fledgling program, supported by a number of well-established Australian rural training programs. The RGPJ teaching program is certified by the Australian College of Rural and Remote Medicine (ACRRM) and registrars who complete training and assessment are awarded the Certificate of Completion of Training jointly by ACRRM and RGPJ13. Internationally, rural generalist medicine (RGM) is commonly defined as a community physician, primary care physician, GP or family practitioner/family physician, credentialed to provide primary and hospital care as well as one or more specialty areas of advanced practice in a rural, remote or regional setting14. However, the definition of RGM has not yet been modified for the Japanese context.

The RGPJ has an identified mission statement that involves:

- improving access to health care for rural and remote areas of Japan

- increasing the rural medical workforce

- increasing the number of doctors pursuing careers in rural medicine

- introducing rural generalism as a concept and a specialty to Japan13.

The training (at the time of interview) is a 15-month program: 12 months at an approved or accredited rural training hospital, online webinars (conducted by a combination of Australian and Japanese supervisors), and a 3-month overseas elective training placement13. Financially, the RGPJ is structured in a way that the hospital site pays the registrar salary and a fee to GENEPRO for additional training and mentoring. In the first 3 years of RGPJ, there were 22 rural medical generalist graduates trained under the RGPJ program across five prefectures13.

The RGPJ presents a unique opportunity to gather the views of a small cohort of registrars and supervisors of the role of RGM in meeting rural healthcare needs of Japan into the future, based on their experience with a small, emerging program. RGM training could be a significant support to the challenge of providing good quality health care for rural and remote Japanese populations. This study aims to gather the views of participants (not only of those associated with the RGPJ but also among academia and government officials) on the future role of RGM in contributing to solutions for rural and island health in Japan.

Methods

Setting and design

This was a descriptive qualitative study conducted in Japan. Data were collected by semi-structured interviews, and the study design was based on an interpretive or hermeneutic phenomenology15. Importantly, an internal evaluation of the RGPJ was conducted concurrently but as a separate project by an independent researcher (TT), who also acted as an interpreter for this project. Due to the timing of these projects and commonality in much of the sample, many interviews were conducted concurrently but with a clear separation in questioning (research questions for this project were conducted first, followed by evaluation project questions). Explanation of both projects and concurrent interview process was provided to participants in writing prior to interviews and again verbally at the interview. This article reports only the research interview findings and not those of the RGPJ program evaluation.

Sample

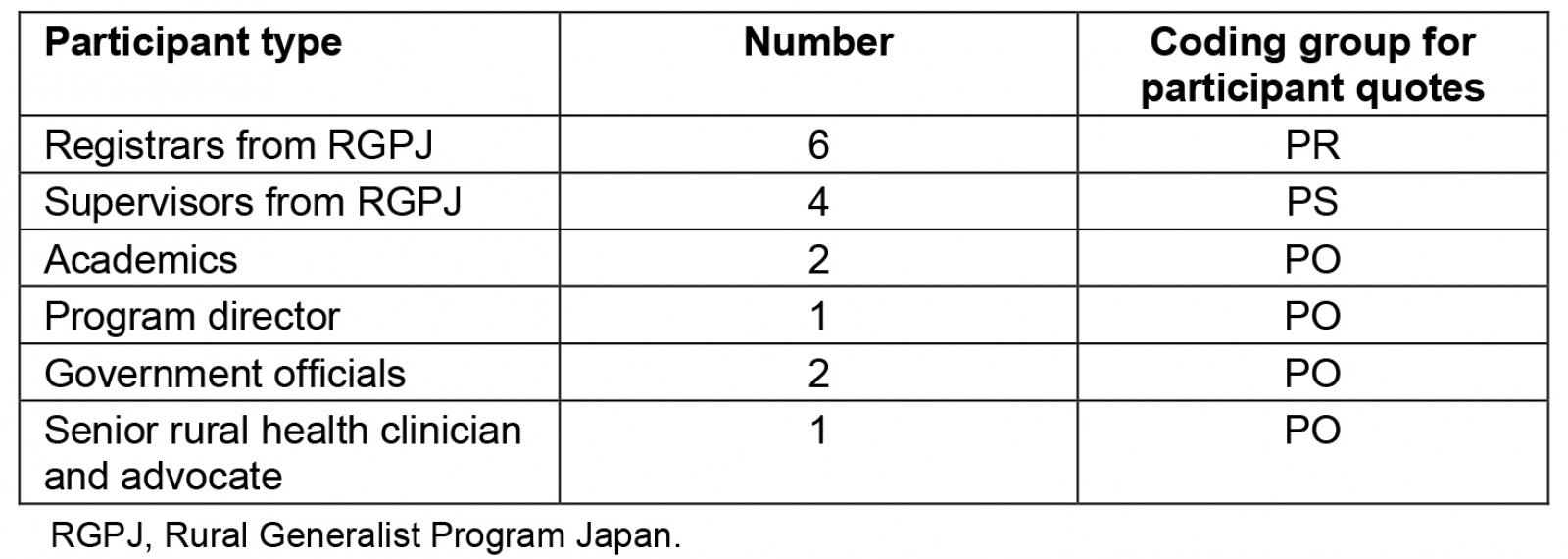

Interviews were sought with all graduates of the RGPJ (cohorts 1 and 2), medical supervisors, government officials, a senior rural clinician, a director of RGPJ and rural health academics. Participant categories are outlined in Table 1. These categories provided a combination of insights into the RGPJ (especially from registrars, supervisors and the director) and broader views of rural and island health needs in Japan and how they may relate to RGM. Participants quoted throughout this article have been broadly grouped and coded as participant registrars (PR), participant supervisors (PS) and participant other (PO), with individual identifiers (A, B, C, etc.) to protect anonymity.

The participants from the RGPJ program were recruited following an invitation to all registrars and supervisors from cohorts 1 and 2. Those that participated in this study responded positively to the invitation. Of the 11 RGPJ registrars at the time, only three responded that they were unavailable for interviewing. Subsequently two more were unavailable to be interviewed, leaving six registrar participants. All of the program supervisors agreed to participate. The two academics were identified from the scoping review process and contacted directly.

All participation was voluntary. An information sheet was provided (and translated) to all participants, and signed consent forms were collected.

Table 1: Study participants and coding

Data collection

An interview guide was developed based on preliminary discussions held with the RGPJ director, several registrars and supervisors in a preliminary field trip (2018), and on issues identified in the literature through a scoping review. Interviews were of 35–50 minutes duration and conducted between May and July 2019. Some interviews were conducted in person at the WONCA Asia-Pacific Conference in Kyoto (2019), some onsite in hospital settings, and some were videoconferenced over Zoom. All interviews were conducted with individual participants, except for two academics who preferred to be interviewed together. Most interviews were conducted in Japanese and translated with the assistance of the translator, except in circumstances where the participant spoke fluent English. All interviews were recorded and transcribed digitally, and the first author also took field notes. All participants were offered the opportunity to request an interview and analysis summary.

Data analysis

Transcripts were coded using NVivo v12 (Lumivero; https://lumivero.com/products/nvivo). The first author (NS) analysed all transcripts and conducted an inductive thematic analysis based on the grouping of codes. This was checked for accuracy and consistency by two co-authors (RE, KB) among a smaller sample of transcripts. All themes identified in this article have been agreed to by co-authors.

Ethics approval

This study received ethics approval from James Cook University (H7472, 07/08/2018). Ethics approval was not required in Japan due to low-risk study design, confirmed by hospital sites and health academics.

Results

From the interview analysis, six main themes were identified: (1) key issues facing rural and island health in Japan; (2) rural generalist participant background; (3) local demography and population; (4) identity, perception and role of RGM; (5) RGPJ experience; and (6) suggested reforms and recommendations. These themes are explored in more detail below.

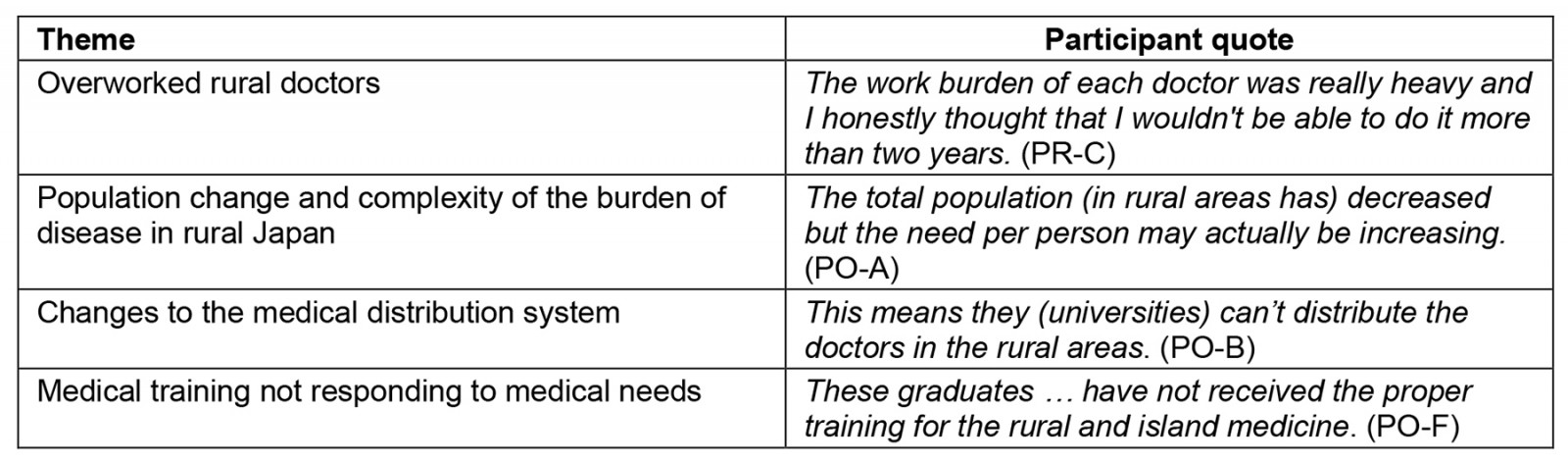

Key issues facing rural and island health in Japan

Participants were concerned about the maldistribution of doctors across Japan, including the shortages in rural and island areas (identified in the introduction). It was identified that rural doctors were generally underrepresented across many specialties and therefore overworked. The aging population in rural and island areas was also considered a key challenge, especially in the context of overall population decline in those areas as younger cohorts increasingly move to cities for work and education. The impact of this was raised by participants as a key problem for policy and training agencies, with a population cohort that is reducing in numbers but increasingly complex in terms of the burden of disease, due to the changing age profile. However, there was a sense of optimism among some that government policies, specifically Chiikiwaku, have yet to be realised and that the effects of these could address shortage issues.

A number of participants also felt that the training of doctors was not responding to the issues facing rural and island Japan. The training issues raised related to both the shortage of doctors in those areas, as well as the complex (clinical) needs of older patients. With regards to workforce supply, the departure from the traditional Ikyoku system of training was considered a contributing factor in the current medical shortages. Ikyoku had traditionally provided university-affiliated hospitals with control over the training and distribution of medical graduates, which was generally considered to benefit the workforce in rural hospitals and clinics. The changes to this system in 2004 favoured graduates choosing their own training pathway and increasingly gravitating toward urban centres8. Many participants also felt that medical graduates were often not equipped to respond to the complex health needs of people in rural Japan, as a direct result of their training program. These participants considered that Japanese undergraduate medical training needs to develop a different kind of doctor with generalist skills specific to the needs of the rural population.

Table 2: Participant quotes on key issues facing rural and remote health in Japan

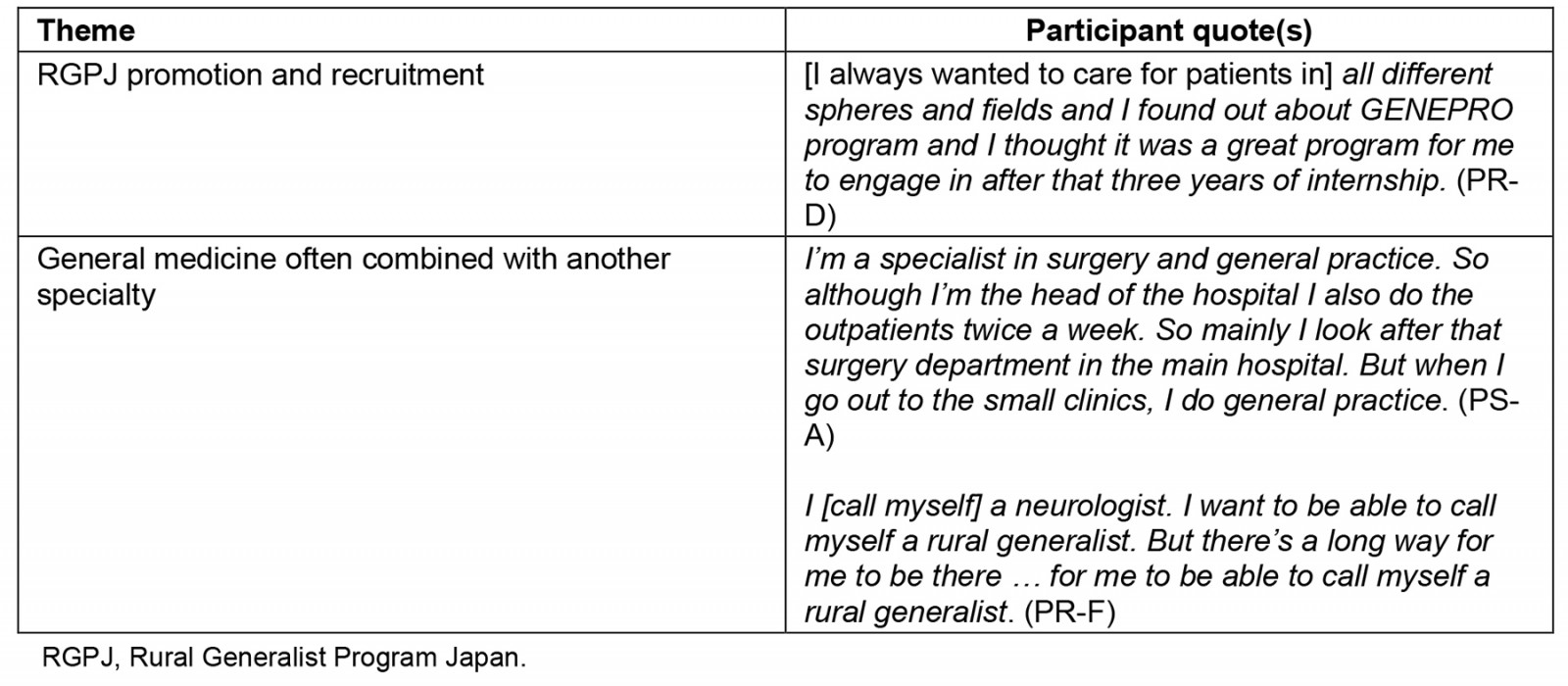

Rural generalist participant background

Interview participants identified several drivers leading them to pursue a career in RGM. One important factor was the strength of the RGPJ in promoting the benefits and learnings of the program. Other important drivers for registrars included their rural background and wanting to provide care back into rural and island areas, having a strong mentor in rural health during their undergraduate training, positive experiences in the undergraduate (rural) placement, and having a desire to expand their medical scope by providing a broader base of care (as required in rural practice).

Another consideration within this theme of participant background is the field of medical specialisation undertaken (or to be undertaken) by registrars in the RGPJ and by their supervisors also working as rural GPs. From the relevant interviews, 62% identified either a pre-existing background in, or an intent to pursue, medical specialties other than general practice or RGM (in addition to their continued practice in general medicine).

Table 3: Participant quotes on the backgrounds of rural generalists

Local demography and population

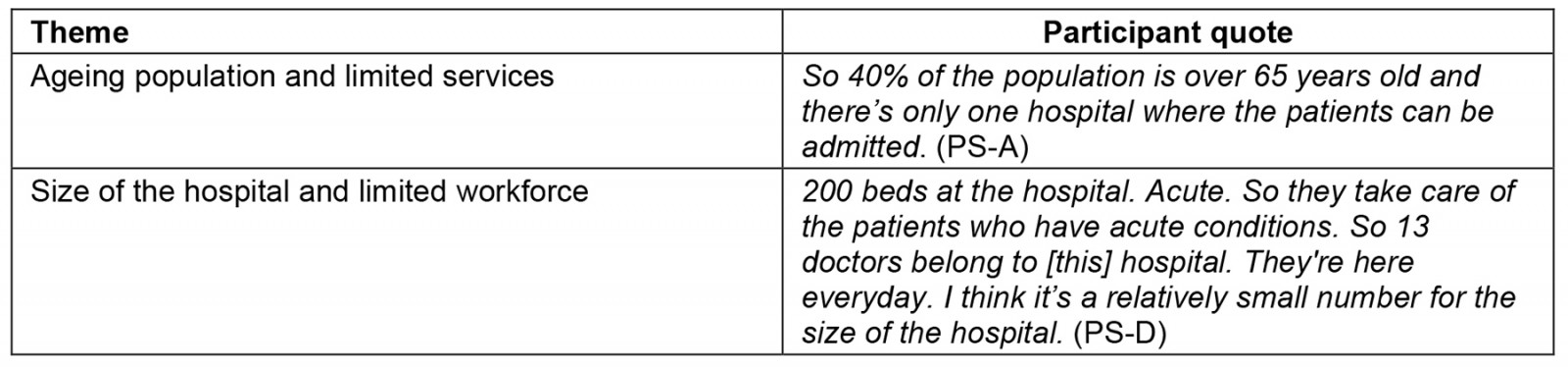

While the issue of needing to define rural, remote or island medicine was not raised, many of the participants provided an overview of the local demography and population in which they served as a means of contextualising the issues they were facing. It was clear that general medicine was a feature of the hospital model-of-care (onsite and/or through home visits), alongside the treatment provided through specialist care. Where the population size served by their clinic and/or hospital catchment was discussed, it was consistently between 20 000 and 50 000 people, ageing and with complex comorbidities. The hospitals in which they worked were generally described as smaller hospitals with between 180 and 200 beds, usually with visiting specialists. In one case it was noted that the hospital only conducted limited treatment services on site and referred to the bigger prefecture hospital for acute, specialist services.

Table 4: Participant quotes on the local demography and population

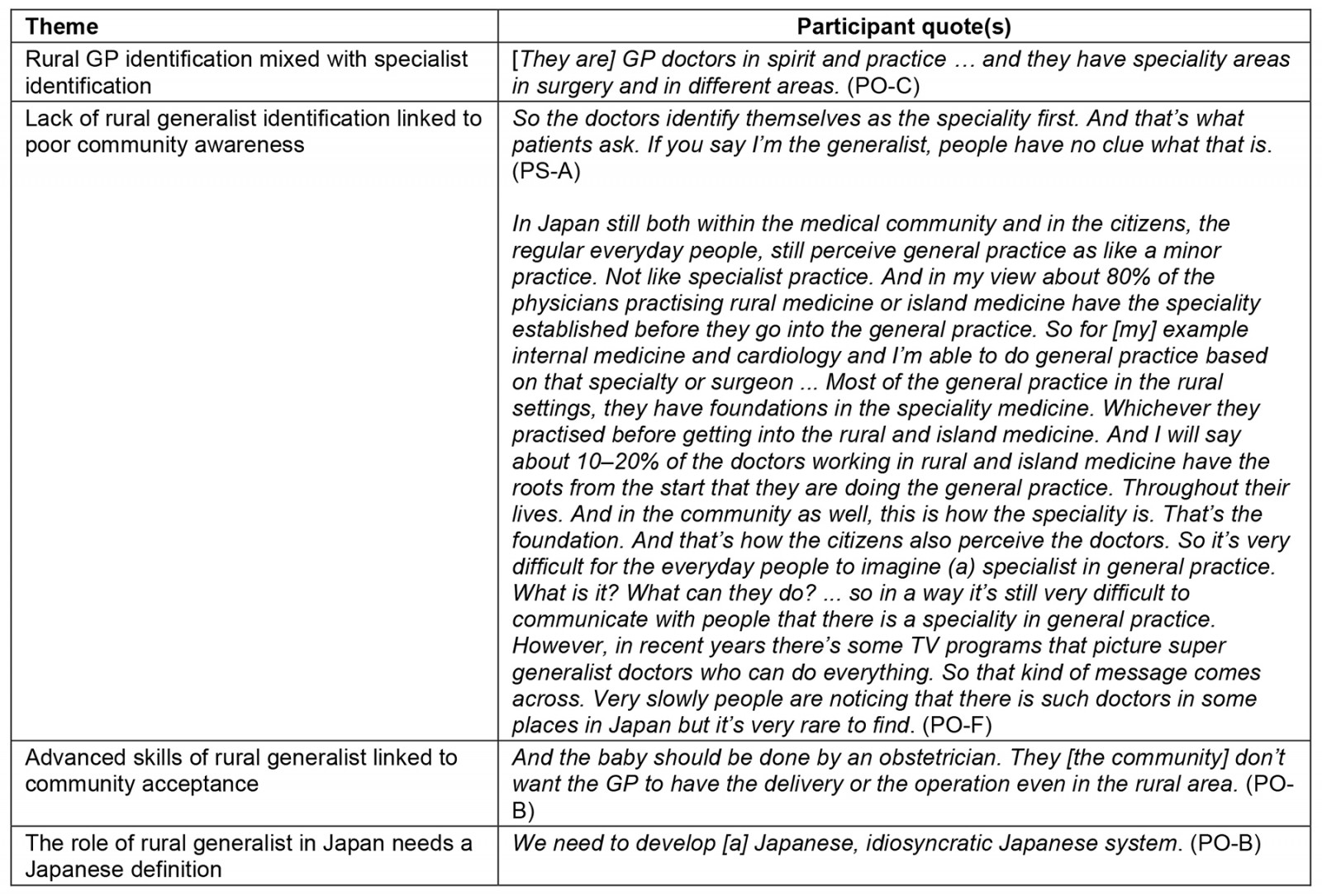

Identity, perception and role of rural generalist medicine

Where it was discussed, half of the trainees said that they identify as a rural GP or rural generalist (in one case the respondent was a supervisor discussing how their registrars in the RGPJ identify). Simultaneously, all those who identified this way also identified as a specialist in another field of medicine. Regarding the remainder (those who do not identify as rural generalists), one commented on how identification is also linked to a lack of community awareness and acceptance of the rural generalist role, which was considered low by participants. However, the response regarding how other medical specialties perceive rural generalism was slightly more positive, with 40% stating that it was well accepted.

All participants discussed what RGM in Japan is and should be, with a focus on the advanced skills needed for rural generalists to meet community need. From interviews, the current advanced skills of rural generalists (in addition to their primary care roles) mainly included procedural skills such as endoscopy and (limited scope) surgery. There were varying views on what advanced skills rural generalists should have in Japan under a more established program. Those more commonly discussed included emergency medicine, orthopaedics, obstetrics and gynaecology (although 50% noted the need for limitations on the scope of advanced practice for RGM), endoscopy, surgery (again 50% noted the need for limitations) and anaesthetics. The most debated of these skills were obstetrics, gynaecology and surgery. Views varied from rural generalists needing to be trained and having full scope of practice to provide quality care close to home, to the rural generalist being more of a support to the specialist, to the rural generalist not being trained in or practising in these skills at all due to the geographic proximity to larger hospitals with trained specialists. In addition, perceptions of the readiness of the Japanese community was a consideration. One participant cautioned against borrowing the advanced skills models from other countries and noted that more work is needed to clearly define the role of the rural medical generalist specific to the health needs of rural and island Japan.

Table 5: Participant quotes on identity, perception, and role of rural generalist medicine

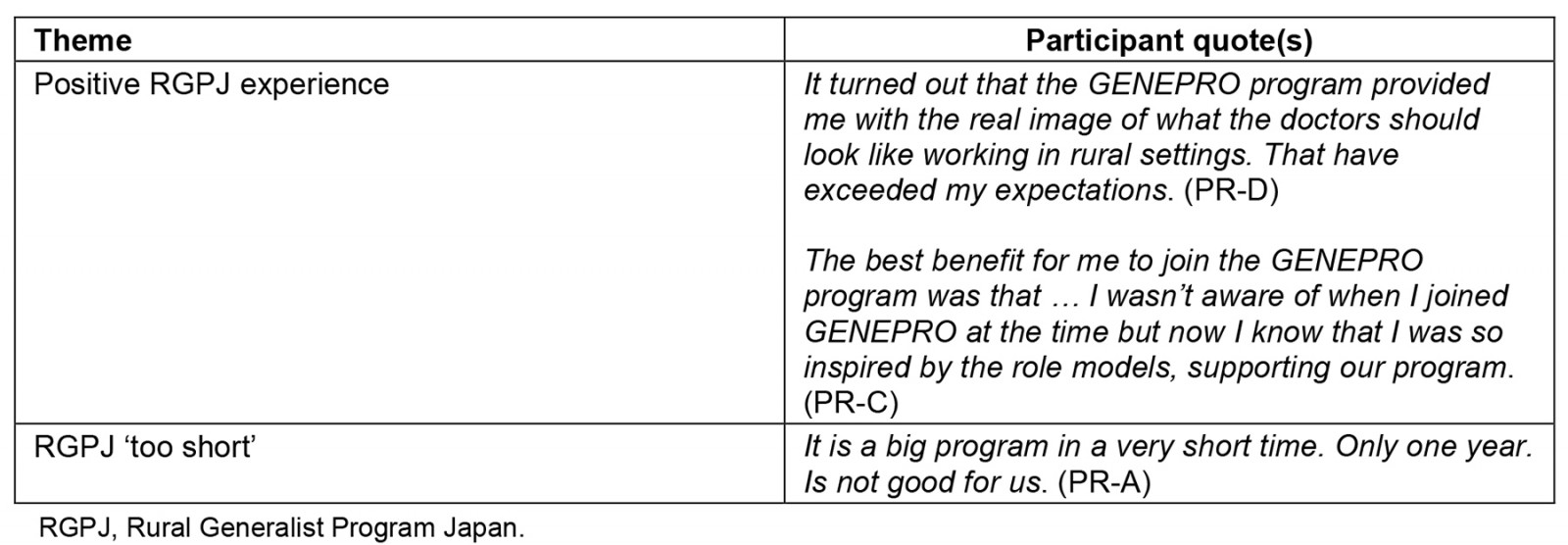

The Rural Generalist Program Japan experience

When questioned about the RGPJ, participants overwhelmingly focused on the strengths of the program, which included:

- providing the registrar with a full rural or island experience, including being trained in a broad range of skills that could not be obtained in urban settings

- providing rural hospitals with new doctors they were not previously able to attract

- recruiting younger, innovative doctors with a passion for rural medicine

- experiencing new and inspiring role models in rural medicine both within Japan and overseas as part of their elective training

- the long-term benefits of the program in graduating registrars who will become champions of rural medicine in Japan.

The negative aspects of the program discussed by participants included the following:

- The length of the placement was considered too short. This was the most discussed criticism of the program. One participant also mentioned that, due to intensity of the rural medicine work, 12 months of onsite training was sufficient and, if the program was longer, it may be difficult to recruit and retain registrars.

- One supervisor highlighted the financial burden to the hospital, especially when paying for the registrar to be away from the site on their international placement. However, the same supervisor felt this was a cost that they were aware of before joining the program and that it was necessary to be able to attract good doctors into rural generalism.

- The program could improve by developing career planning to create a long-term pathway for graduates.

- There is a need to establish more formal communication lines between the hospital, the RGPJ and the registrar during the 12-month training program to ensure the needs and progress of all are being met.

- Occasionally the international learning opportunity was attracting doctors looking for an overseas experience rather than a rural medicine career in Japan.

- Another participant suggested the RGPJ could recruit more Japanese rural GPs to serve as mentors and role models to the RGPJ registrars.

- One participant mentioned that there should be more focus on teaching registrars to listen to, and work closer with, their patients on the care that they provide.

Table 6: Participant quotes on the Rural Generalist Program Japan experience

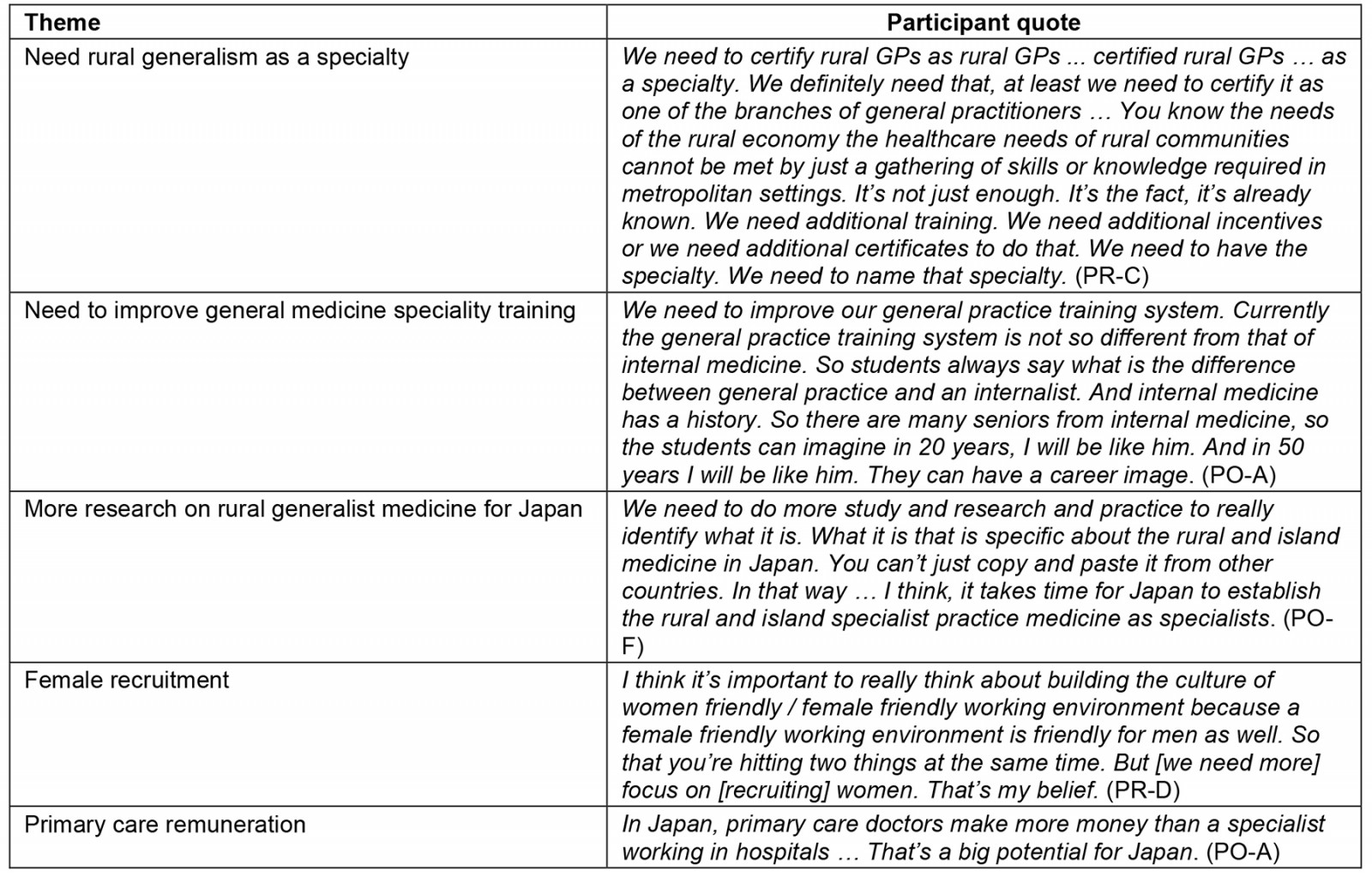

Suggested reforms and recommendations

Aside from the suggested improvements to the RGPJ, there was also a broader discussion on reforms needed to address the issues of rural and island medicine in Japan. A common topic was the need to establish a national approach to RGM in Japan. One participant suggested that the model developed by the RGPJ needs to be scaled up with a collaboration between all levels of government and the Japanese Primary Care Association. They argued that such national approach to RGM also needs to include recognising certified rural GPs as a standalone specialty. Another indicated that the Japanese government is aware of, and supportive of, the concept of scaling up a national approach to RGM but has indicated that many of the hospitals and prefectures were not yet prepared for such a program. This also reflects a discussion by another participant around the need for more research in preparing the Japanese rural health system (in addition to the community) for such a reform in implementing a large-scale national RGM program.

Other suggestions for reform included the need to:

- mandate rural training placements

- mandate a cap on all specialty training numbers as a means of encouraging more registrars to undertake GP training

- improve the newly established general medicine specialty training to attract more entrants to the program

- create a safer working environment for female doctors in rural and island areas to encourage greater representation

- establish a rural outreach ‘hub and spoke’ model controlled through a centralised prefecture hospital system

- develop and better utilise technology to provide care remotely into rural and island settings.

The current general medicine training program was a strong focus of these discussions. Participants indicated that the low uptake in the new specialty is related to a combination of inhibiting factors, including problems in effectively administering and promoting the new program and a lack of clear distinction from internal medicine in the general medicine training program itself. One of the suggestions was that more established GPs in Japan need to be recruited into helping shape and deliver (and therefore improve on) the general medicine training program. Another participant also discussed this confusion between general practice and internal medicine as being a barrier to recruiting more trainees. It was suggested that the role and associated training program need to be branded as general medicine, rather than general practice, which in Japan is more closely aligned to hospital-based internal medicine. Another participant expanded on this suggesting that rural general medicine needs to be separately branded and promoted, and then also recognised as a separate specialty in Japan.

It was also raised that, unlike in many countries, general medicine remuneration in Japan was not generally considered a barrier to recruitment, with payments often matching those of other specialties. This was considered a positive for the new general medicine specialty and something that could be promoted more to improve graduate recruitment. There was also a sense of optimism for existing reforms such as Chiikiwaku and more recent changes to legislative framework enabling greater powers over workforce distribution to prefectures. Participants suggested that both still need more time to develop before seeing the impact on medical workforce distribution. It was also mentioned that a national workforce distribution modelling project was only recently completed to support these reforms.

Table 7: Participant quotes on reforms and recommendations to the Rural Generalist Program Japan

Discussion

Primary health care and the role of GPs has a complex and political history in Japan1,10. The recent recognition of general medicine as a specialty is an effort to build the generalist role and primary care workforce3. However, early results indicate there is still more work to be done11. These findings show that the lack of an established general medicine pathway has also impacted on the general awareness and acceptance of primary care roles in Japan. This lack of general awareness and acceptance in rural and island areas also negatively impacts on the self-identification by some rural doctors as ‘rural generalists’. Improving community acceptance, graduate recruitment and the self-identification (and therefore branding) of rural generalist doctors all need to be addressed to improve primary care practice in rural and island areas of Japan.

The establishment of the RGPJ has generated interest and discussion among the participants of this study in the potential for RGM in Japan. It was generally considered to be a positive step toward reshaping the medical workforce to address the inequities in health outcomes and the complexities associated with a rapidly ageing population. While granular improvements to the program were suggested by participants, it was also generally agreed that it provided the foundation for consideration of a more systematic, national approach to RGM programs and recognition in Japan. The development of a national RGM pathway and the need to separately recognise rural generalism are both consistent with recommendations of other nations to encourage RGM as a means of addressing rural and remote health disparities14. It also reflects broader international collaborations to define the role and scope of RGM, such as the Cairns Consensus Statement, and could also consider other international research and evidence around the elements of RGM training and support that impact on rural workforce14,16,17.

A number of key findings from this study would be important in developing a nationalised approach to a Japanese RGM. This includes the discussions on the drivers to participating in the RGPJ (in considering recruitment to a national program) and the need for an idiosyncratic Japanese model of RGM, with agreed advanced skills and supervision models. Where RGM roles exist internationally, there is some commonality in the procedural advanced skills discussed in this study, in particular obstetrics and gynaecology, anaesthetics, emergency medicine and surgery14. One of the departures from other international models based on the interviews in Japan is the agreed view that endoscopy should be (and even currently is in some areas) part of the rural generalist role. However, from these interviews, there is debate to be resolved in Japan around the appropriateness (or at least scope) of advanced skills in obstetrics, gynaecology and surgery. More discussion would also need to occur on non-procedural advanced skills in a Japanese RGM model. In other countries these generally reflect the context in which the role is practised and can include Indigenous health, paediatrics, mental health, radiology, palliative care and elder care14.

Limitations

The background scoping review undertaken specifically for this study excluded articles not published in English. Despite this, 33 articles were included for review.

Another limitation of this study is that all participants were male, due to no female registrars being available. This may more broadly reflect an issue raised by one participant (and in one article) of the male dominance in Japanese medicine3. The sample size of participants for this study was small, reflecting the size of the RGPJ and the limited broader discussions and planning for RGM in Japan at the time. Despite these limitations, it is likely that the findings will be of relevance for the number of small, developing RGM programs emerging internationally, including in the Pacific.

Conclusion

The challenges facing health services, medical educators and policymakers in rural and island Japan are very familiar to those faced by many countries with rural and remote geographies. However, there are some challenges unique to Japan. Its relatively small land mass is characterised by thousands of islands and a very large population. In rural and island settings of Japan, primary health care has typically been practised by specialists in other fields in small outpatient clinics or small hospitals10. General medicine has only been certified as an accredited, recognised specialty since 2018 and there are continued challenges to develop an awareness and acceptance of primary health care in a system in which patients can attend a tertiary care facility without referral, despite more recent efforts by government to disincentivize this1.

RGM as a rural health service and workforce strategy had previously been considered academically in Japan8 but, until the RGPJ, no specific funded and supported program of rural generalist training had previously been implemented. The RGPJ represents an effort to bolster the national rural medical workforce. Discussions from participants in this study indicate strong support to continue research, exploration and expansion of a RGM model that is contextualized for Japanese conditions and that is branded and promoted more broadly to build community support for the role of the rural generalist. Alongside other reforms related to general medicine training and medical workforce distribution that were identified in this study, there are many lessons from the RGPJ to continue momentum toward a national Japanese model for RGM.

Funding

The initial scoping for this study was part-funded by the Rural Generalist Japan Program.

Funding for the data collection and subsequent research costs for this project was provided by James Cook University College of Medicine and Dentistry as part of Higher Degree by Research resource funding.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.