Introduction

Adolescence is a critical period in the development of mental illness. Worldwide, three-quarters of all mental illness develops before the age of 25 years1. One in four young Australians aged 16–24 years experience a mental illness each year2. While rates of mental illness are the same across rural and urban communities, outcomes for Australian rural residents are worse3. Suicide is the leading cause of death in young people aged 15–24 years, with the rate of suicide in rural and remote Australia being over 50% higher than in cities4.

Rural and remote communities are heterogenous, incorporating a diverse range of physical and social environments. While there are similarities between rural and remote communities, such as proximity to the natural environment and less anonymity, remote communities are generally smaller and more isolated, with reduced resource allocation5.

A growing body of literature has explored the impact of rurality on mental health and wellbeing across all ages. A range of stressors have been identified as being unique to rural communities; these include environmental challenges such as climate change, drought, floods and fires; higher rates of chronic disease and poorer health overall5; lower levels of income and limited employment opportunities; economic insecurity; reduced access to technology and communication systems; and reduced transport opportunities6. Additional negative sociocultural factors associated with a rural location include rigid cultural norms and stigma, increased family violence, higher rates of alcohol and drug use and more rigid gender roles6-8. Furthermore, reduced access to services6,9-11, stigma associated with mental illness10,12,13, concerns regarding lack of confidentiality12 and reduced help-seeking behaviour compared with urban residents14 have been identified as factors contributing to poorer mental health outcomes.

Counter to these challenges are protective factors inherent in a rural address: living in a clean environment, having a sense of community and connectedness, greater self-efficacy, safety and enjoying a more relaxed lifestyle7,10. People living in rural areas generally score higher on wellbeing surveys than those living in urban environments3. Social capital in rural communities is high, particularly in the areas of sense of community and social connection15. Furthermore, services in rural areas can be more personalised and flexible10. Some characteristics of rurality are perceived as double-edged swords. The culture of self-reliance and stoicism in rural communities has been cited as both a strength and challenge11,16. The power of word of mouth can act as a barrier to help-seeking, as well as facilitator10.

The geographic, cultural, social and economic milieu that impacts mental health in rural communities has been widely documented6-8,17-20. Furst et al formulated these influences into an ecosystem approach that explicitly addresses the influence of the socioecological system on mental health and wellbeing21. Ecological systems theory describes human development as the result of interactions between a person’s biological characteristics with the proximal influences of family, school and work, and the more distal social and cultural structures21. Influenced by Bronfenbrenner’s ecological theory, the ecosystem approach explores the rural context through levels of influence that incorporate personal, community, and overarching sociocultural systems22.

However, few studies have addressed how rural ecosystems impact specifically upon the mental health and wellbeing of rural young people, defined as those aged 12–24 years23. While the available literature is limited, evidence shows that young people living in rural and remote areas face additional social and economic challenges. With reduced options for education and training beyond high school, they are often required to move away for further education24. They are less likely to be employed, have lower incomes in general, and pay more for goods and services than those living in capital cities5.

Furthermore, the limited explorations of factors contributing to poorer mental health outcomes in rural youth have primarily included adult voices. Jensen et al documented clinician experiences of barriers to rural mental health care25; others explored caregiver perceptions of the impact of rurality on youth mental health(10}. The research identified by the authors that included youth participants has largely explored social barriers to help seeking and access to appropriate services26,27.

This article presents results from a study exploring young people’s perceptions of how the rural setting influences their mental health. Utilising an ecosystems approach21, the study explores the complex interplay of factors that impact on rural youth wellbeing, allowing for the development of nuanced and contextually appropriate approaches to improve mental health in this at-risk demographic. Understanding the influences on rural youth mental health allows for the exploration of interventions that amplify the protective aspects of rural living while mitigating the risk factors.

Methods

Research design

The study utilised qualitative methods, based on a phenomenological interpretive approach28. Underpinned by this methodology, the study aimed to elicit personal narratives to draw out the rich complexity of individual, interpersonal, community and social structures of a rural community that impact on youth mental health and wellbeing. The study was guided by the principles of participatory action research (PAR) in which rural young people were actively involved in the research process29,30. A study reference group was formed that included five young people, the local high school nurse and the CEO of a not-for-profit organisation supporting at-risk young people in the community. Utilising PAR principles, the reference group advised on engaging and recruiting participants, developing a plain language explanation of the study, as well as ensuring study questions were relevant and understandable to the study group. Due to concerns around the maintenance of confidentiality in a small community, the reference group was not engaged in data collection or analysis.

Setting

Participants were recruited among young people aged 12–19 years living in a small rural community in southern Western Australia. The town has a population of around 3000 people, with approximately 5500 living in the shire; it is situated approximately 100 km from the nearest regional centre31. The study setting is a farming community, which is also supported by tourism and mining. The town has two primary schools and a single district high school that has approximately 200 students and runs to year 10, requiring students to travel outside of the town to further their senior school education. The town has a local hospital and two medical practices. There is youth centre, a police station, recreation centre and public library, along with several cafes, a pub and several grocery stores. There are active sporting clubs covering a range of disciplines. The community has a relatively small number of First Nations people, constituting 1.6% of the local population (compared with 3.2% of the Australian population31).

Sample

In the study community, there are approximately 450 young people in the target group of ages 12–19 years31. This age group was selected because, following high school graduation and a gap year, many young people leave the region to pursue employment and/or further education. Those young people aged over 19 years who remain in the community experience different stressors and support networks to the younger cohort and will be the subject of a separate study.

Recruitment

Participants were recruited using a multipronged approach including social media advertising, targeted approaches to sporting clubs, youth centre advertising and direct invitation by reference group participants. A purposive sampling technique was adopted to ensure diversity of age, gender and mental health status. Key contacts within the health, education, recreation and community services sectors were informed about the study via email and in person, and were invited to advertise the study through their professional networks. Following this, additional participants were recruited by snowball sampling.

Data collection

All participants provided written informed consent, with parental consent being required if aged less than 16 years. Participants completed a brief demographic questionnaire prior to participating in the interview. This included a self-rating score of their current mental health from 0 to 10, with 10 being excellent, and whether they had past or current mental health problems. In-person, semi-structured interviews were conducted. The interviewer was a youth worker who received training in research interview methodologies. Participants were offered the option of being interviewed in a group or individually. Participants who elected to be interviewed in a group formed themselves into focus groups with their peers, resulting in them being same-gender and of similar ages. The interview schedule included open-ended questions inviting participants to discuss their experiences of living in a rural community, particularly in relation to the impact of this context on their mental health. Each interview was audio-recorded and lasted approximately 60 minutes.

Data analysis

The audio recordings were transcribed and imported into NVivo v1 (Lumivero; https://lumivero.com/products/nvivo). The transcripts were subjected to thematic analysis. Data analysis was largely inductive, but was influenced by socioecological theory, especially in the identification of themes. In the first instance, and following multiple readings of the transcripts, codes were identified and grouped into categories and subcategories. Influenced by the ecosystems conceptual framework21,22, themes were identified and refined until consensus was reached among the research team.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was provided by the University of Western Australia Human Research Ethics Office (reference RA/4/20/6367).

Results

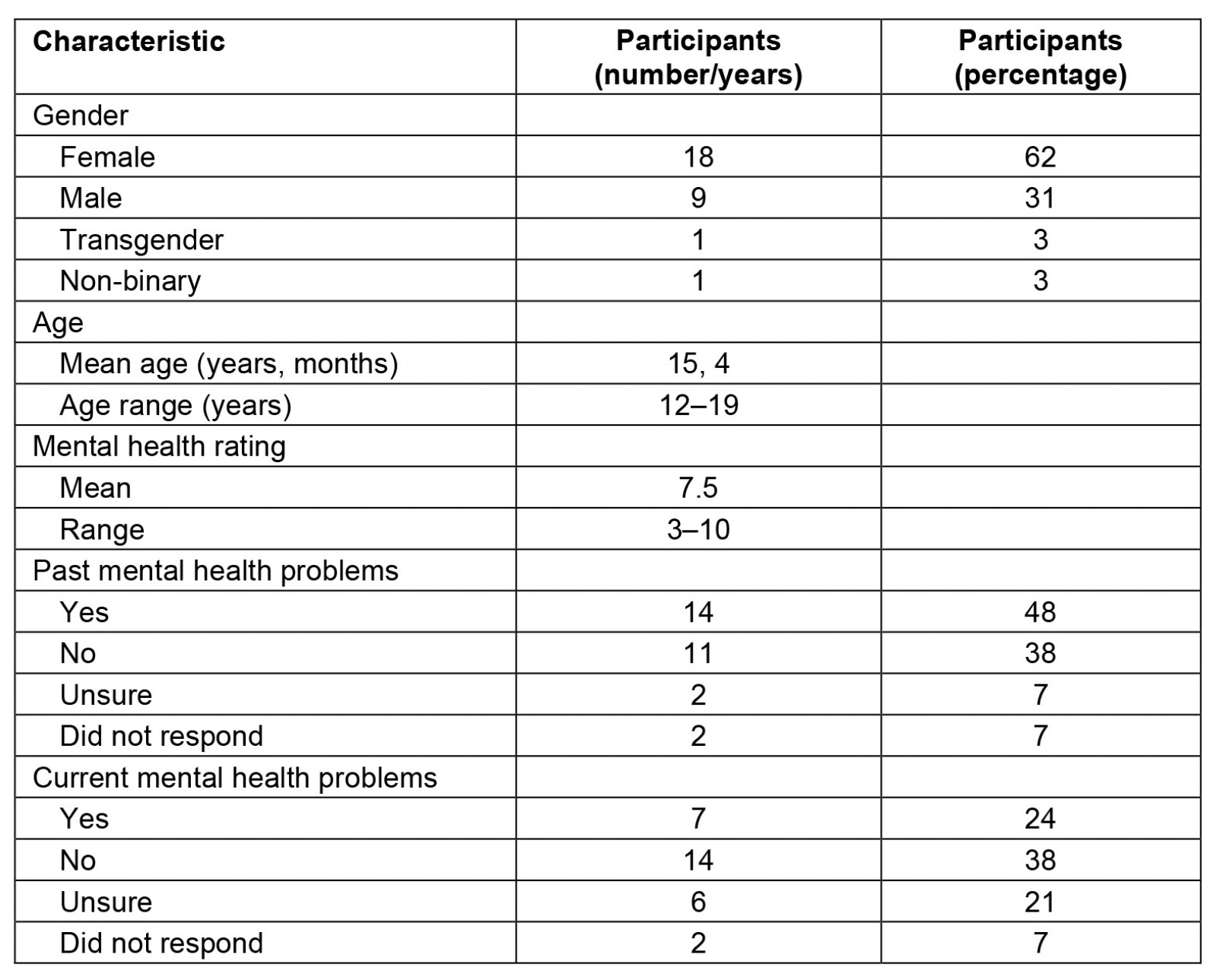

The study included a total of 29 participants with an average age of 15 years, 4 months, ranging from 12 to 19 years (Table 1). Nine participants elected to be interviewed individually, and the remainder were in six focus groups with 3–5 participants per group. Study participants’ demographics were weighted towards females, consistent with the literature, with young men being less willing to talk about personal issues32,33. The average self-rate mental health score was 7.5/10. In line with population data, around half of the sample identified as having had past mental health problems, while a quarter had current mental health problems2,34.

Three themes emerged from the data: ‘everyone knows everyone’, ‘a small school and beyond’ and ‘the place’, aligning with the spheres of influence as described by socio-ecological theory22. Quotes from participants are presented to illustrate the content. To ensure participants’ confidentiality, pseudonyms are used, with an indication of age and gender. Of interest, there was no clear alignment in individual participant responses to being generally positive versus negative. In fact, most participants described both positive and negative aspects to each theme, acknowledging both the strengths and challenges inherent in their rural location.

Table 1: Demographic and background characteristics of participants (n=29)

Everyone knows everyone

Almost every participant reflected on the impact of a small community on their interpersonal relationships. Young people highlighted friendships as being a key protective factor for mental wellbeing, providing a strong sense of belonging and support. Most participants attributed their close friendships to living in a smaller community where ‘everyone knows everyone’. Several young people felt that their friendships benefited from them living close to each other, often within walking distance, so that they could spend a lot of time together.

In our small town everyone kind of knows each other and they can tell when someone's down and you go out of your way and ask how they are and sometimes that makes others feel better and that can even make someone a lot happier. (Abbey, female, 15)

Having intergenerational relationships within and between families was acknowledged by several participants as being valuable and supportive. Others acknowledged the merit of living in a tight-knit community during times of stress or natural disaster, with support readily available.

I know people that their grandparents live on the same property as them and their cousins go to the same school as them, their aunties and uncles live in the same town and they’re all connected and have this big support group. (Matilda, female, 13)

Paradoxically, some participants reflected on these close social connections negatively, as they spoke about the potential of conflict or a lack of diversity in small social networks to lead to isolation.

I think that people’s mental health can be impacted heavily by people. If you know everyone in a town and then something happens with those people and they turn your back on you, you can feel you don’t have anyone, and that can lead to certain issues. (Charlotte, female, 15)

Multiple participants commented on gossip spreading quickly within a community and the consequent negative impacts on their mental wellbeing. Grudges, judgement and ‘long memories’ can embed lasting negative attitudes and reputations. This can impact opportunities, including employment and access to housing.

You probably get more drama in [a country town] because stuff spreads easily … once something spreads, it’s stuck. Spreading like spreading your butter on a piece of toast. Once it spreads around the whole piece of toast, it’s not coming off. (Ben, male, 14)

Similarly, one young person discussed the impact of a family’s reputation as leading to judgement and stigma.

If a certain family is known to do a certain thing or act a certain way, they get classified, and then their children get treated differently because that’s what their family’s like. I think that’s a big issue in [town] as well, is that people judge everyone very quickly and label everyone, and yeah, just – Some families would be known for drugs or whatever they’re known for, and their child is treated differently because of it. (Charlotte, female, 15)

One young person (Jay, trans male, 14) spoke of his peers being ‘racists, homophobes, ableists’. He described the negative impact this had on his mental health. This theme was similarly discussed by three female participants in a focus group, who commented that the community had narrow stereotypical expectations of young people in terms of ‘race, culture, weight, appearance, family life’ (Beth, female, 14).

Two participants expressed ambivalence about the influence of living in a small town on their friendships. Emma (female, 18) described it being more difficult to make friends because ‘you basically know everyone already’, while at the same time it’s easier to meet up with local friends without having far to travel. Similarly, Jo (non-binary, 18) described finding it harder to find friends and feeling isolated living in a small town yet felt closer to the friends they do have because they spend more time together.

Strong interpersonal relationships also impacted on perceptions of the availability of support services. Almost half the participants felt that they were more easily able to access mental health support in a rural community as they had existing relationships with support staff. Eleven participants felt that service providers were more engaged in supporting them because ‘they know us’ and 'actually care’.

I think it would be worse in the city, maybe, if you had mental health problems. You don’t have a sense of community and it can be harder to find someone you trust, maybe, to share any feelings or thoughts. (Jay, trans male, 14)

In contrast, one participant felt that she would be more likely to access mental health support in a larger centre where she would not have personal connections with the local therapist.

It’s just really hard to see someone at school, because you’re going to see them every day. That’s the same with [local psychologist], I didn’t want to see [local psychologist] because I was so scared that if I saw her she would see me differently outside of sessions and that, and that’s so scary … And I was so scared that she’d tell mum something and that just freaks me out. (Matilda, female, 13)

A small school and beyond

The influence of school and its small size on young people’s wellbeing was a strong theme. Young people described feeling very supported by staff who knew their history and were able to identify if the young person was struggling. They felt staff were personally invested in supporting them to get well.

You feel like you have more support in a smaller school, knowing that all the teachers know who you are. (Abbey, female, 15)

Again, participants expressed contrasting opinions on the impact of their small school size on their wellbeing. Two young people felt that the small school impacted on educational opportunities, particularly for those who had special needs or struggled with certain subjects, as the smaller number of teaching staff meant choices were limited. One young male, however, aged 13, felt that the smaller class sizes were beneficial as he was able to get more attention from his teachers.

A frequently identified negative aspect of the local high school was that it only runs until year 10 (ages 15–16 years), requiring years 11 and 12 students to travel outside the community to complete their high school education. Most young people identified this as a stressor. This was largely due to having to leave their cohort and establish themselves within a new group of peers, leading to feelings of disconnection from their hometown friendship group and wider community. Five participants, who all identified as having experienced mental illness in the past, felt that lengthy daily travel requirements to senior high school contributed to fatigue and anxiety. Some students were not able to access the school bus service, meaning family members would have to drive them to and from senior school, a 60 km round trip. Young people raised the financial and time implications of this and the impact of this on their families.

So many of my friends got so mentally unwell through our year 11 and 12, purely because they were in a place where they didn’t want to be and that they physically couldn’t handle. (Ebony, female, 18)

In contrast, three young people in a focus group who attended high school outside of their community felt this was positive for their mental health, allowing them an opportunity to ‘have a break’ when they came back to their hometown if things were stressful at school. One participant reflected on the larger schools having more friendship and interest groups. She felt that in smaller schools ‘quite a lot of people are very parochial and quite narrow minded’ (Beth, female, 14). Ebony, aged 18 years, felt that having to leave town to complete high school was a useful stepping stone to moving further afield for tertiary education.

Reduced employment and educational opportunities beyond high school were highlighted by several participants as a challenge, with the need to leave town to further education or employment being linked to feelings of stress and uncertainty about the future. A small number of young people were positive about having to leave their community as they felt there would be more options, allowing them to broaden their experiences and opportunities. One participant expressed ambivalence about having to leave her family and hometown for further education, acknowledging this as a stressful life event, but also as an opportunity for developing independence and personal growth.

The place

‘The place’, incorporating natural, socioeconomic and cultural environments, emerged as a strong influence in young people’s sense of wellbeing.

A third of young people interviewed spoke about the natural environment. Using terms such as ‘quiet’, ‘relaxing’ and ‘less crowded’, they reflected on the natural environment allowing them opportunities to find space and connect with nature, positively impacting on their mental health and wellbeing. A similar number spoke about feeling physically safe in their community.

The most significant difference in responses between males and females was in relation to the impact of the environment on their mental health, with male participants placing greater value on ‘the place’ in their responses. Again, a paradox was described in which the strengths of a natural environment intersected with perceived risks such as limited access to organised sports and retail outlets.

Several of the male participants appreciated the ability to ride motorbikes freely in the bush around town and have access to mountain bike trails and camping spots near the river.

You know which places to go if you want to go somewhere to clear your head or something. You know which places are best just to sit there and watch the sunset or something. (Angus, male, 17)

In contrast, participants discussed the challenges of geographic isolation, with transport being a key topic. Several young people identified lack of public transport as limiting their options for socialising, employment and playing high-level sport. Jay (trans male, 15) described feeling physically ‘stuck in town’. Lack of transport led to several young people expressing a sense of isolation.

While only six participants reported that they had previously lived in an urban area, the majority of young people drew comparisons between real or perceived, often idealised, differences between rural communities and urban centres and the impact of different locations on mental wellbeing. Young people felt that urban centres offered more opportunities for recreation and socialising. They expressed idealistic beliefs that city life equalled easy access to shops, movies, beaches and fast-food outlets, which would enhance their wellbeing. Many felt that unless you are engaged in sport, you can feel very bored and isolated in a small town, while cities are better able to cater to a variety of interests.

[In the city] There’s more extracurricular activities for everyone, so everyone can find their niche and their interests, what they’re passionate about. (Suzanne, female, 15)

The counter opinion of a small number of young people was that a rural life allowed more recreational freedom and opportunities. Three male participants stated that they could more easily enjoy adventure sports. Interestingly, two of the six participants who had previously lived in the city felt that there are a diverse range of activities on offer in the rural community that are more easily accessible.

Most of those interviewed felt that living in a rural community placed them and their families under economic strain. Financial pressures included local shops being more expensive with no access to budget stores and limited choice, travel out of town being expensive due to high fuel costs, and services being generally more expensive. The financial impact of having to move to the capital city of Perth following high school for further education and training was also seen as a stressor. Several participants shared perceptions of family work-related stress. One participant described her parents needing to work multiple jobs as there was no single role that was suitable. Another spoke of his parents working 12-hour days, 7 days a week, on the family farm, and the stress this caused their family.

Discussion

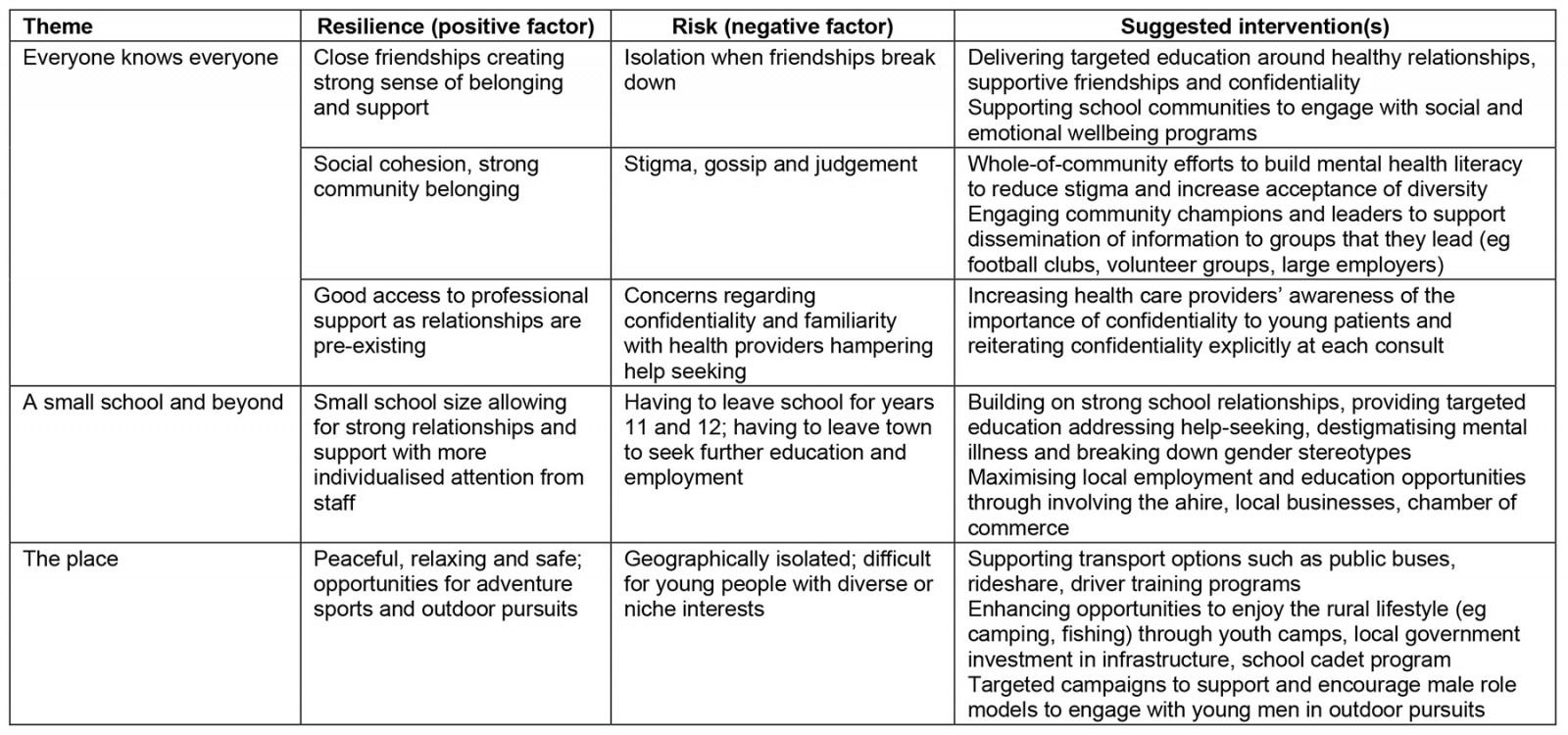

The study builds on research that has examined the dichotomy of rural communities from a deficits and strengths base7,35,36. Jonsson et al describe Swedish youths’ experiences of health services in rural areas as being ‘landscapes of care and despair’27. This study complements Jonsson’s findings by focusing on the impact of rurality on mental health itself, rather than access to care. The study explores the rural paradox through an ecosystem lens, highlighting the spheres of influence on rural young people’s mental health. The results provide opportunities to reflect on how the seemingly contradictory responses in all ecological levels can be reconciled, through building protective factors and mitigating risks (Table 2).

The notion of ‘everyone knowing everyone’ had positive and negative connotations. While this is not a new concept from the perspective of caregivers10, this was clearly articulated by the youth voice, reflecting the high importance placed on interpersonal relationships in adolescent development. It is important to acknowledge the influence of these relationships in young people’s lives: optimising the strengths of these relationships while acknowledging the challenges inherent in such close connections. For example, providing targeted education around healthy relationships, conflict resolution and managing confidentiality can provide young people with tools to build and enhance meaningful relationships.

Similarly, close relationships between young people and mental health providers had paradoxical responses. On one hand, participants felt they would seek help more readily from professionals whom they knew and who ‘cared about them’. On the other hand, they felt that knowing the professional could act as a barrier to help seeking due to fears of confidentiality being broken. This highlights the importance of health providers in rural communities always maintaining the highest standards of professionalism and relational dynamics. Explicit reiteration and demonstration of confidentiality for young people is paramount in small communities.

Concerns about the stigma of mental illness in rural communities is reflected widely in literature with adult participants10,36. This study demonstrates that stigma is experienced by adolescents, with fear of gossip and judgement tangibly impacting on wellbeing and hampering help-seeking. Several participants discussed the impact of gender stereotypes and gender identity in their community on their mental wellbeing. Addressing rural stereotypes, perpetuated by more conservative views of masculinity and gender roles, contributes to intolerance towards young people who, in particular, are gender or sexually diverse33. Interventions to build mental health literacy could reduce stigma and increase acceptance of diversity.

Boyd et al considered the impact of social capital on rural youth mental health, ‘the 'glue' that holds society together’15. Our study affirms the value of social capital in participants’ mental wellbeing, with participants identifying community support, a sense of belonging and connection to community being strong protective factors. Social capital in rural communities is intrinsically high and can be further enhanced through interventions that improve community cohesion: engaging the community in common goals and grassroots projects that produce positive results for rural youth15.

In rural settings, schools have been identified as playing a critical role in supporting young people with mental health concerns, including linking them to supports36,37. Our study highlights young people’s perceptions of the powerful, largely positive, influence of the school setting, and teachers, on their wellbeing. This should be intentionally exploited, by providing targeted education that addresses help-seeking, destigmatises mental illness and breaks down gender stereotypes.

In contrast, the need to travel to larger centres for higher levels of education can result in significantly increased additional stress for young people in rural towns24. Our findings highlight the importance of maximising local education and employment opportunities in mitigating some of the key stressors for rural young people, being employment, education and further training. Relocation assistance for those who are required to leave the community to further education and training would also reduce some of the expressed financial burden.

The impact of the natural environment on young people’s wellbeing should not be underestimated, with most study participants appreciating the space, safety and recreational opportunities rural settings afford. It is valuable to note that there was a strongly gendered response to this theme, with males expressing a high level of appreciation for the recreational opportunities afforded to them. At the same time, many participants described a romantic notion of city life, one that is filled with endless opportunities for social and recreational activities. This concept has been documented in adult literature since the 1940s7, describing a duality between rural and urban life that reflects either ‘heaven’ or ‘hell’. Community efforts to support young people to value their rural lifestyle, while acknowledging their urban idealism, would be valuable to promote youth wellbeing and balanced expectations in the information and digital world. Given the high rates of male suicide in rural areas, policies should capitalise on the positive impact of rurality on young males’ wellbeing, encouraging traditionally male-orientated activities that enhance their sense of belonging and engagement.

The study is not without limitations, beginning with the single location and community. As such, themes may be location-specific, hence impacting on external validity and generalisability of the findings across rural heterogeneity. Similarly, our sampling technique may have resulted in a biased, non-representative sample. Participants were geographically accessible, available to attend the interviews outside of school time (hence not reliant on school bus services) and were willing to participate. The sampling process may have excluded young people who were geographically and socially isolated. Inarguably, these would be highly valuable voices. Furthermore, with a dominance of female participants, gender differences were largely unable to be established.

Table 2: Summary of paradoxical responses with mental health interventions to build positive factors and mitigate risk factors

Conclusion

Rural communities and the people within them are heterogenous. Some experiences of young people in this study can be generalised to many rural and remote communities, for example, the easy access to the natural environment. Others are more place-based and context-specific. Our study brings into focus the importance of considering the factors that are common to rural communities as well as the unique contextual and place-based factors when exploring solutions to improve the mental health and wellbeing of our young rural residents.

The study findings support the view that mental health in rural youth is best viewed through an ecosystem lens, acknowledging the complex and dynamic interplay between interpersonal, community and environmental factors on young people. The paradoxes and contradictions present in almost every interview are informative, instructive and of great value in considering the needs and desires of rural young people.

The study asserts the value of models of care that focus less on mental health service provision and more on the impact of community and place on youth wellbeing. Further investment in the widely recognised, but infrequently implemented, value of youth mental health programs that address the social and ecological determinants of mental resilience is highlighted by the study findings. Current metrocentric funding and commissioning models of care for youth mental illness do not address the impact of the unique socioecological influences on rural youth wellbeing. The Orange Declaration, while not specific to young people, addresses the need for mental health service delivery to be systemic, integrated and contextually appropriate38. Rural communities have the capacity to respond rapidly with innovative solutions and models of education, healthcare and community development that are relevant to their communities. Rural communities should be supported to build upon their intrinsic strengths to ameliorate the impact of rurality on mental health risk factors for young people. Building on the assets inherent in rural communities, could rural young people have better outcomes than urban youth?

I just love living here. It’s so nice and it makes me happy. There’s no place like home. (George, 12)

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the funding support of the Lishman Health Foundation.

The authors also thank the young people who shared their stories and experiences. We thank the participants in the reference group and particularly Lisa Burgess for her leadership in this group and her assistance in data collection.

Funding

Funding was received from the Lishman Health Foundation.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

You might also be interested in:

2015 - Satisfaction with local exercise facility: a rural-urban comparison in China