Introduction

Anaemia is a prominent women’s health concern worldwide, particularly in lower- and middle-income countries and it has also been associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes1-3. WHO defines pregnancy anaemia as a haemoglobin concentration less than 11.0 g/dL. Anaemia becomes a serious public health issue when its prevalence reaches greater than 5.0% of the population4. Globally, the prevalence of anaemia in pregnancy is 36.8%, with the highest prevalence in Africa (41.7%), followed by Asia (40.0%)5. A nationally representative survey in Indonesia, Basic Health Research, reported that the prevalence of pregnancy anaemia in the country increased from 37.1% in 2013 to 48.9% in 2018, and in 2018 the prevalence in pregnant women aged 15–24 years was 84.6%6,7.

Iron deficiency anaemia (IDA) is the most typical anaemia in pregnancy. During this period, the risk of iron deficiency increases following the increased demand for iron in the mother for the formation of red blood cells, and placenta and fetus development. IDA is associated with poor birth outcomes, including preterm birth, cesarean delivery, blood transfusion, low birth weight and low APGAR (appearance, pulse, grimace, activity, respiration) score8,9. In severe cases, IDA may increase the risk of maternal death and adverse fetal development10,11. Also, it has a long-term impact on children’s psychomotor and neurocognitive development, as well as mental health8,12.

Following global recommendations13, the Indonesian government made several efforts to reduce IDA in pregnancy. One of these was providing pregnant women with daily iron–folic acid supplementation (IFAS) during antenatal care visits14. IFAS treatment for 90 days every consecutive day during early pregnancy has been linked to reduced maternal anaemia and improved birth outcomes13. However, such a program is not without constraints. Various factors affect antenatal IFAS in low- and middle-income countries. For example, an Ethiopian study found that women did not take IFAS due to a lack of access to health facilities during pregnancy and limited information on the utilization of IFAS15. Delays in pre-existing anaemia diagnosis and treatment, poor access to IFAS and limited antenatal care counselling on IFAS recommendations are reported reasons for IFAS underutilization in Niger16. Poor access and quality of antenatal care services (eg low IFAS supply, inadequate counselling to encourage IFAS consumption) were barriers to antenatal IFAS in seven African and Asian countries17. In Indonesia, antenatal IFAS is challenged by a lack of coverage, various brands in which iron–folic acid content does not meet the standard, consumption that does not start early in pregnancy, low quality of IFAS education and lack of database18,19.

Previous studies have identified factors influencing adherence to taking IFAS, including antenatal care visits, previous history of anaemia, knowledge of anaemia, knowledge of IFAS and suggestions from husbands15,16,20-22. A systematic review study has shown that pregnant women who obtained information about IFAS and had adequate knowledge about IFAS were twice as likely to have good adherence to IFAS20. IFAS can also be influenced by socioeconomic factors such as maternal education23,24 and household wealth24-26. However, existing studies have shown mixed results, including in Indonesia15,16,23-26.

Socioeconomic inequalities may pose a significant challenge to optimal IFAS adherence. While earlier studies have suggested socioeconomic inequalities in IFAS23,27, these were limited to the analysis of determinants adjusted for socioeconomic strata, with no particular analysis aiming to quantify socioeconomic inequality. Some nationally representative Indonesian studies have been conducted to identify factors associated with IFAS among pregnant women. Nevertheless, there were differences in how the outcome was measured, such as receiving iron tablets28, the consumption of iron tablets29, the consumption of at least 90 iron tablets26 and the non-utilization of IFAS24. Other Indonesian studies only involved small sample sizes30,31 and restricted geographic areas30-32. To our knowledge, no socioeconomic inequality study in adherence to IFAS has been conducted in the Indonesian context. Therefore, the present study aims to fill research gaps by examining social determinants and socioeconomic inequality in adherence to antenatal IFAS in rural and urban settings in Indonesia. Findings from this study may contribute to formulating appropriate policies and interventions to enhance antenatal IFAS adherence, thus better maternal nutrition and health outcomes.

Methods

Data source and study population

We used nationally representative data from the 2017 Indonesia Demographic and Health Survey (IDHS), the most updated DHS data for Indonesia. Administratively, Indonesia consisted of 34 provinces in 2017. Provinces are the largest subdivisions, followed by municipalities/districts and rural–urban villages. Using a two-stage stratified sampling design, the survey applied probability proportional to size to select primary sampling units or census blocks. The unit size was the number of households based on the 2010 population census. The census block was then stratified by rural–urban villages with implicit stratification in each stratum by sorting the census block based on the wealth index category. After that, 25 households were chosen systematically from each census block. Finally, the present study included all women aged 15–49 years with a child born in the 5 years preceding the survey. IDHS provides detailed information on sampling procedures elsewhere33.

Outcome variable

The outcome variable was antenatal IFAS adherence. We used two IDHS questions to determine the utilization of IFAS: ‘During this pregnancy, were you given or did you buy any iron tablets or iron syrup?’ and ‘During the whole pregnancy, for how many days did you take the tablets or syrup?’33. We then categorized the adherence to IFA supplementation as ‘less than 90 tablets’ or ‘90 or more tablets’.

Explanatory variables

We included several social determinants of health as our explanatory variables based on WHO’s theoretical framework of social determinants of health34, previous research findings of factors of IFAS adherence24,35,36 and the availability of variables in the 2017 IDHS33. We then grouped these variables by several characteristics of the women (age, educational level, occupation, birth number of current pregnancy, weekly media exposure, weekly internet access, involvement in decision-making), household factors (husband’s educational level, household wealth), healthcare factors (antenatal care visits) and community factors (urban or rural residence, geographic region). Household wealth was estimated using the principal component analysis on a cumulative wealth score for each household based on assets, including amenities and infrastructure. Based on these scores, households were then ranked in five equal categories, each with 20% of the population: poorest, poorer, middle, richer and richest33.

Statistical analysis

First, we used descriptive statistics to obtain the proportion of IFAS adherence across the explanatory variables. Taylor series linear approximation was applied to estimate the 95% confidence interval (CI) around its proportion. Second, we performed univariate logistic regression to examine the relationship between each explanatory variable and the IFAS adherence measured by crude odds ratios (OR). Third, we included variables with p<0.25 to multiple logistic regression to create a full baseline model. We kept the mother’s age28,35, mother’s educational level24,35,36, maternal involvement in decision-making24,36, household wealth24,35 and place of residence24,35 as fixed variables in the multivariate analysis, regardless of their significance. We used a manual backward elimination method to remove the least important variables one by one beginning with the baseline model. We presented adjusted odds ratios (AOR) in the final model.

Last, we used maternal education and household wealth as indicators of socioeconomic inequalities37. We determined the socioeconomic inequalities in IFAS adherence using the Wagstaff normalized concentration index for the binary outcome38,39. We also plotted the concentration curve to present the cumulative proportion of IFAS adherence (y-axis) against the cumulative proportion of the women, sorted by their education and household wealth (x-axis)40. A positive value for concentration index or a curve below the line of equality means that IFAS adherence is more concentrated among higher socioeconomic groups. Conversely, a negative concentration index or a curve above the line of equality suggests that IFAS adherence is more concentrated among lower socioeconomic groups. A zero value indicates the absence of socioeconomic inequalities41.

We used Stata v17.0 (StataCorp, https://www.stata.com) for all statistical testing and applied ‘svy’ commands to adjust the complex sampling design by including sampling weight, strata and cluster. We set the level of significance at p<0.05.

Ethics approval

The 2017 IDHS received ethics approval from the Institutional Review Board of ICF International (reference number: FWA00000845) and was conducted after acquiring the written informed consent of the study participants, adhering to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The present study uses publicly available data for scientific use with de-identified information and was thus exempt from ethics approval.

Results

Characteristics of study participants and proportion of iron–folic acid supplement adherence

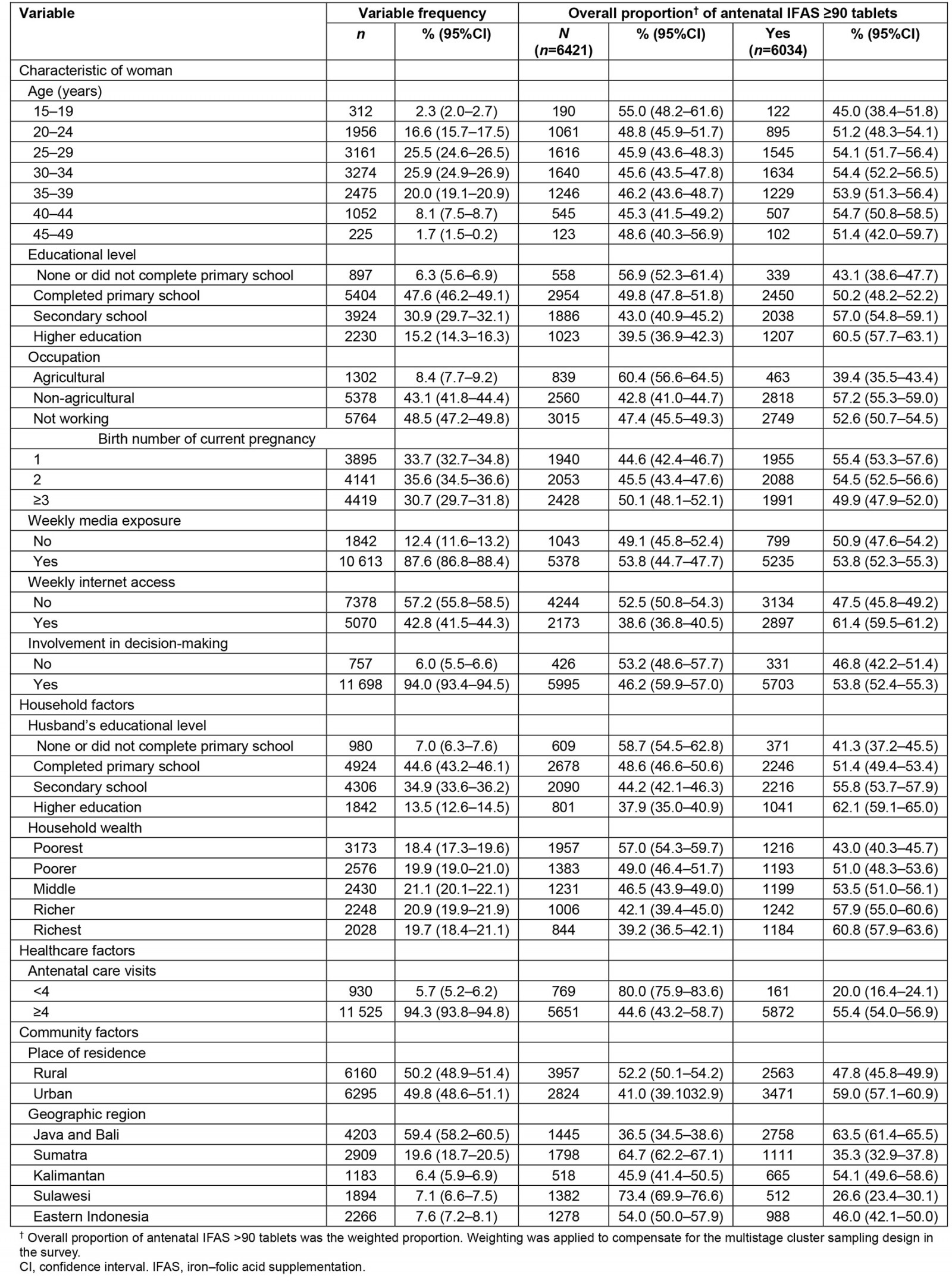

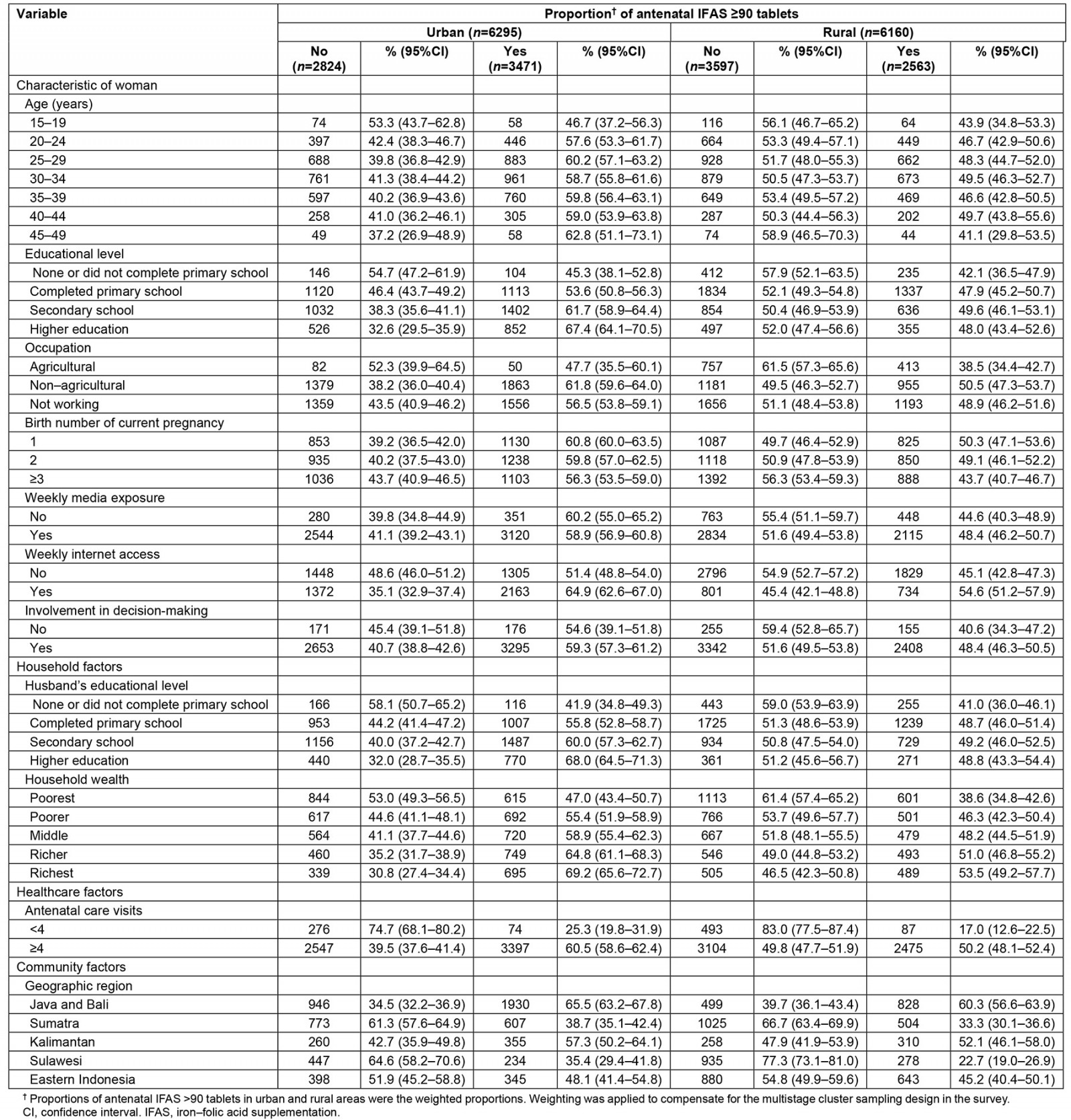

Table 1 presents the distribution of adherence to antenatal IFAS across different determinants. We included a total of 12 455 women aged 15–49 years in the analysis. Overall, the percentage of adherence to antenatal IFAS was 53.4%. The proportion of adherence to taking at least 90 tablets was lower among women with the following characteristics: aged 15–19 years (45.0%), no or incomplete primary school (43.1%), working in the agricultural sector (39.4%), without weekly internet access (47.5%), not involved in decision-making (46.8%), whose husbands had none or incomplete primary school (41.3%), from the poorest families (43.0%), with fewer than four antenatal care visits (20.0%). The proportion of IFAS adherence was higher among those who lived in urban areas (59.0%), and in Java and Bali (63.5%). Table 2 shows detailed proportions of adherence to antenatal IFAS in urban and rural areas.

Table 1: Characteristics of study participants and proportions of antenatal IFAS adherence in Indonesia (n=12 455), based on data from 2017 Indonesia Demographic and Health Survey

Table 2: Characteristics of study participants and proportions of antenatal IFAS adherence in urban and rural Indonesia (n=12 455), based on data from 2017 Indonesia Demographic and Health Survey

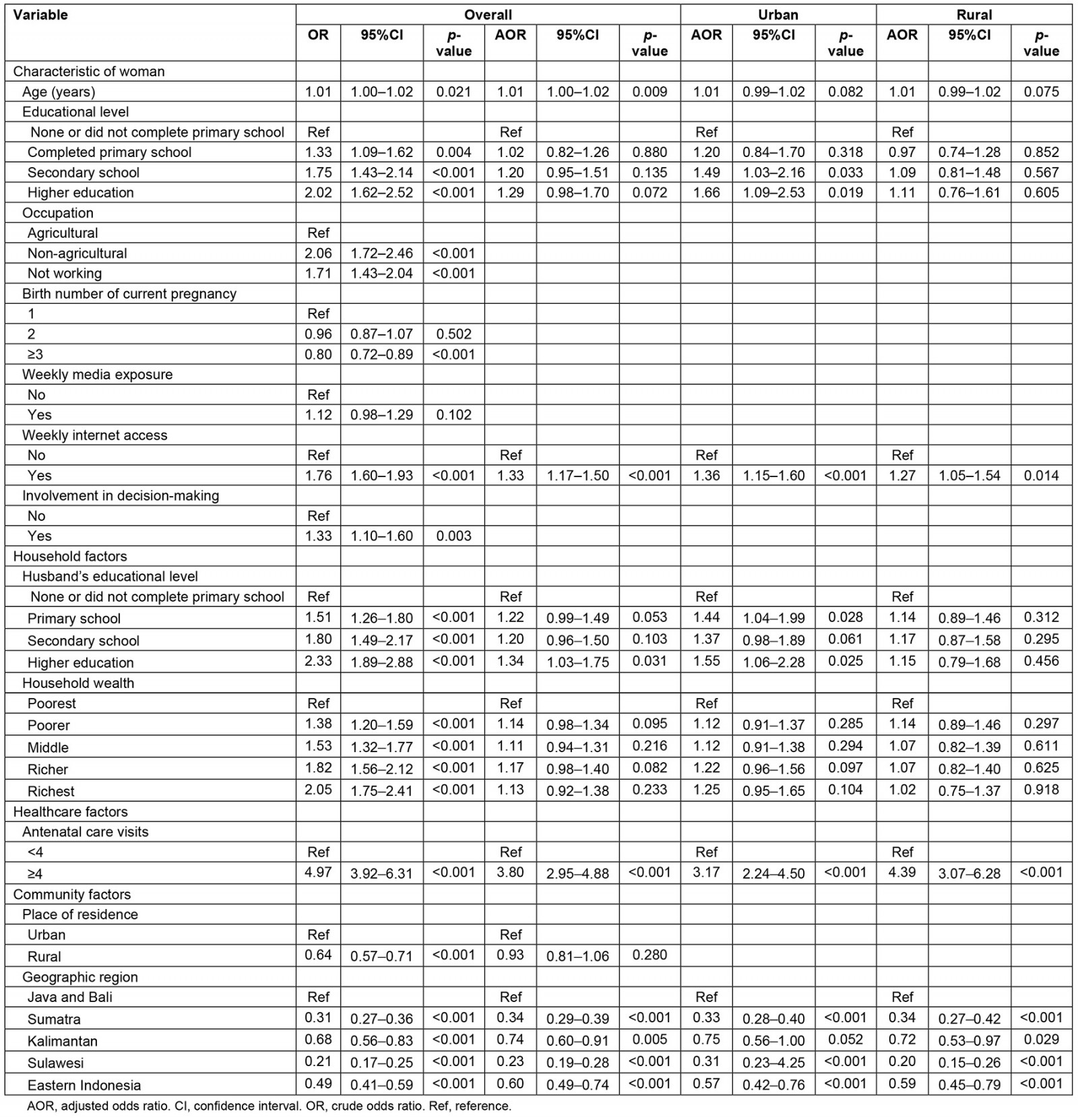

Social determinants of iron–folic acid supplement adherence

Table 3 presents crude and adjusted odds ratios of IFAS adherence determinants. Overall, the likelihood of IFAS adherence increases with the women’s age. In other words, the results showed that a 1-year increase in maternal age was associated with a 1% improvement in relative risk for overall IFAS adherence (AOR 1.01; 95%CI 1.00–1.02, p=0.009). However, we found no association between the woman’s age and IFAS adherence when analysing the relationship based on urban (AOR 1.01; 95%CI 0.99–1.02, p=0.082) and rural (AOR 1.01; 95%CI 0.99–1.02, p=0.075) areas. There was no significant relationship between the woman’s educational level and IFAS adherence, except in urban areas indicating that completing secondary school (AOR 1.49; 95%CI 1.03–2.16, p=0.033) and higher education (AOR 1.66; 95%CI 1.09–2.53, p=0.019) was associated with IFAS adherence among urban women. Our study shows that weekly internet access was significantly related to IFAS adherence across the living areas.

Altogether, although Table 3 shows that women whose husbands completed higher education had 34% greater odds of consuming IFAS (95%CI 1.03–1.75, p=0.031), particularly, urban women whose husbands completed higher education had 55% higher odds of taking IFAS (95%CI 1.06–2.28, p=0.025). No significant association could be identified between the husband’s education at all levels and IFAS adherence in rural areas. Despite a dose–response relationship between household wealth and IFAS adherence in bivariate analysis, we found no significant association between these variables after adjusting for other variables. Women with a history of antenatal care for at least four visits were three to four times more likely to take IFAS across the place of residence. Compared to those who lived in Java and Bali, women in all regions were less likely to consume IFAS, except for urban women who lived in Kalimantan (AOR 0.75; 95%CI 0.56–1.00, p=0.052).

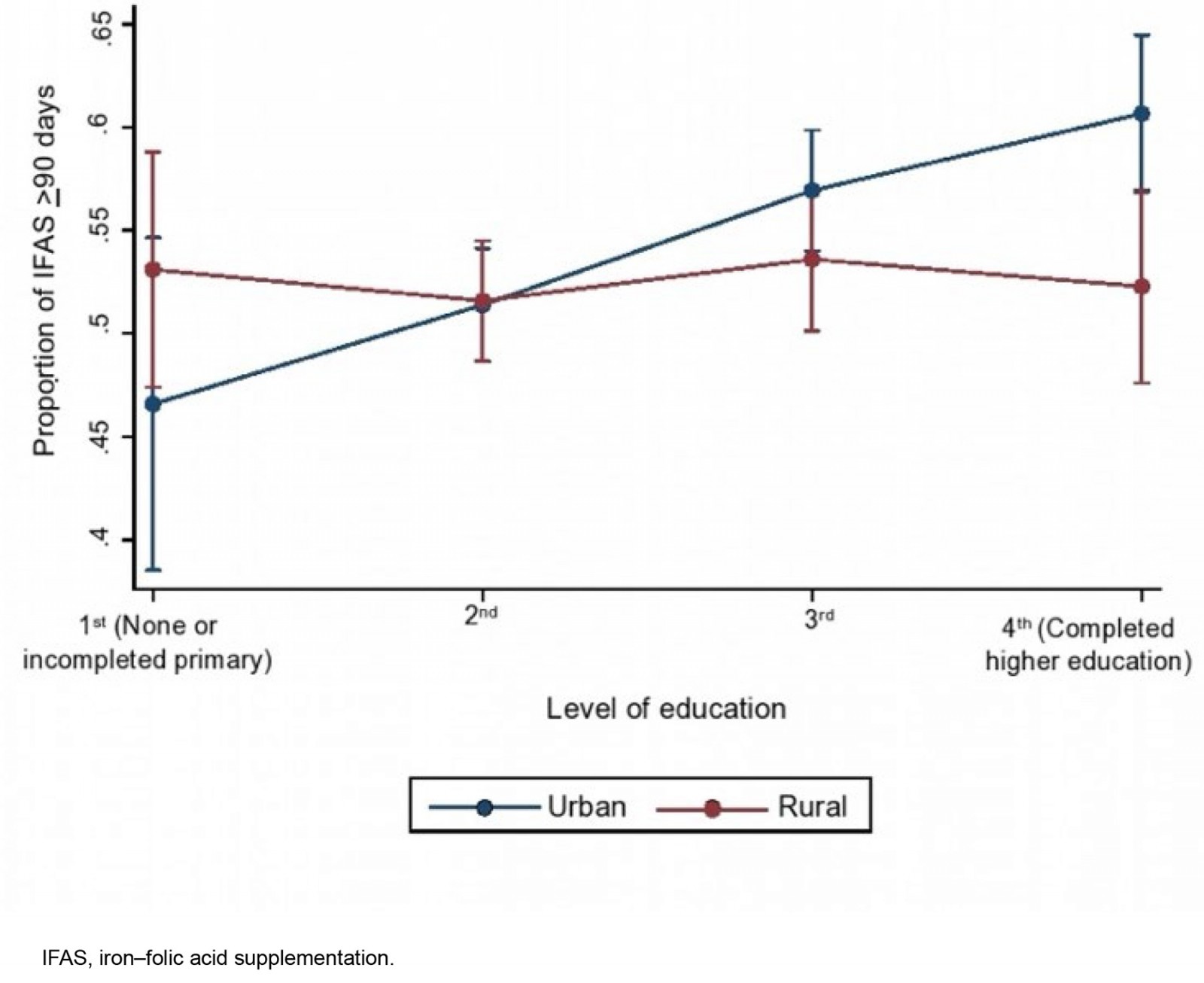

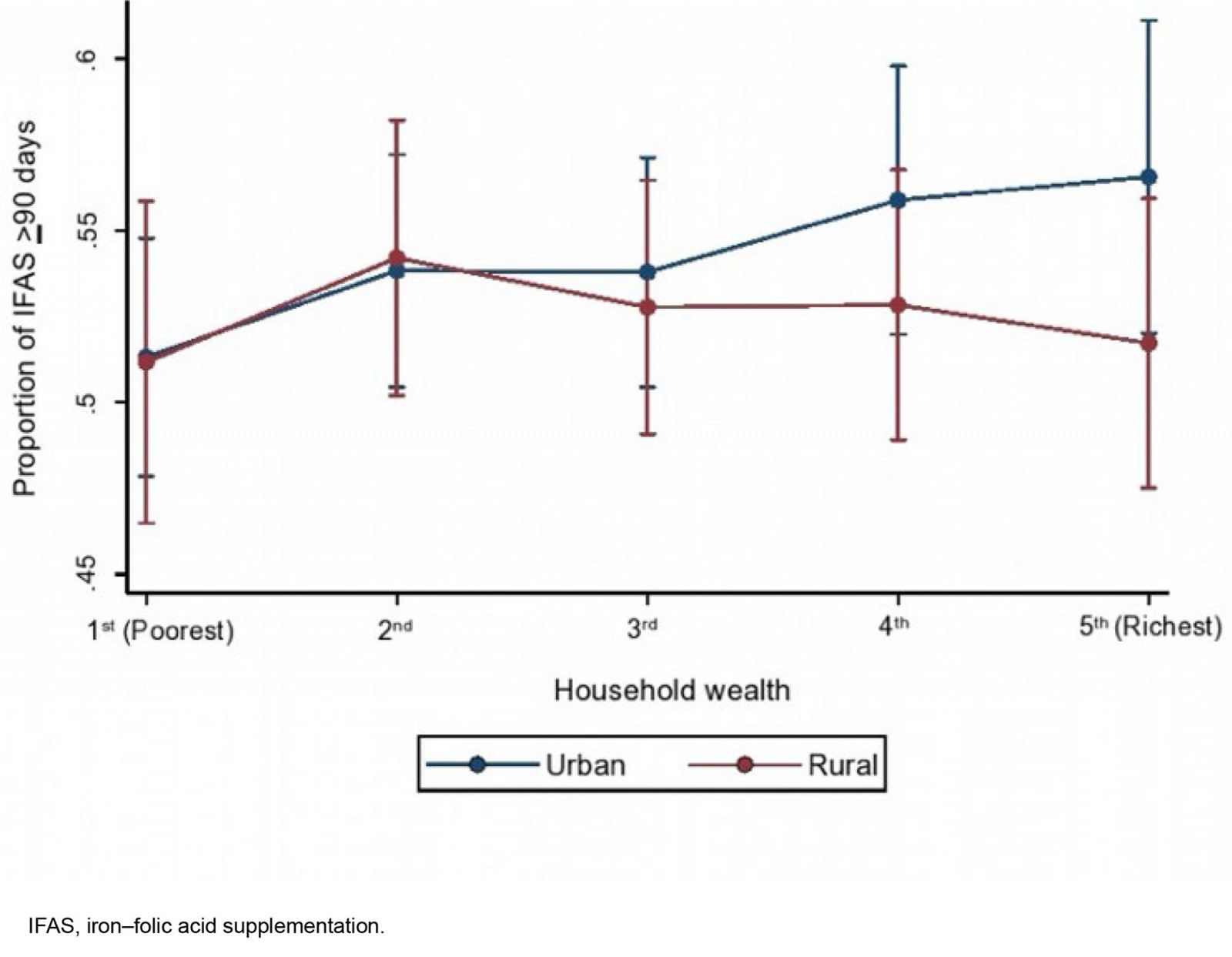

Furthermore, we performed interaction analyses between woman’s education and place of residence, and household wealth and place of residence. Figure 1 depicts that the probability of IFAS adherence generally increases with the level of education among women residing in urban areas but remains stagnated in rural areas. In urban areas, the probability of IFAS adherence is higher for those who completed secondary school or above. Likewise, Figure 2 presents the probability of IFAS which gradually increases with household wealth in urban areas but shows no considerable change across household wealth in rural areas. The probability of IFAS adherence in urban is higher for women with middle income and above. Overall, the difference in probabilities of IFAS adherence across place of residence changes across women’s educational attainment and household wealth, suggesting interaction effects.

Table 3: Determinants of antenatal iron–folic acid supplementation adherence among women aged 15–49 years in Indonesia showing crude and adjusted odds ratio, based on data from 2017 Indonesia Demographic and Health Survey

Figure 1: Combined effect of woman’s educational level and place of residence (p<0.001), based on data from 2017 Indonesia Demographic and Health Survey.

Figure 1: Combined effect of woman’s educational level and place of residence (p<0.001), based on data from 2017 Indonesia Demographic and Health Survey.

Figure 2: Combined effect of household wealth and place of residence (p<0.001), based on data from 2017 Indonesia Demographic and Health Survey.

Figure 2: Combined effect of household wealth and place of residence (p<0.001), based on data from 2017 Indonesia Demographic and Health Survey.

Socioeconomic inequalities in iron–folic supplement adherence

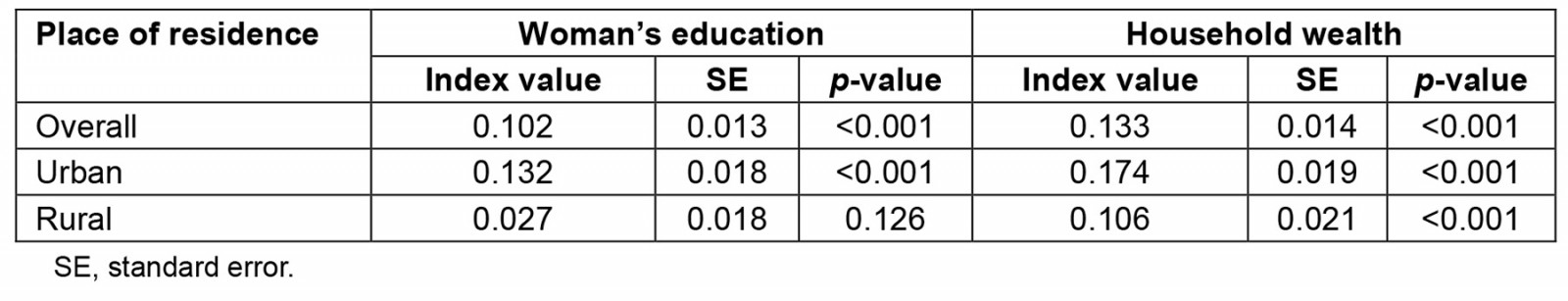

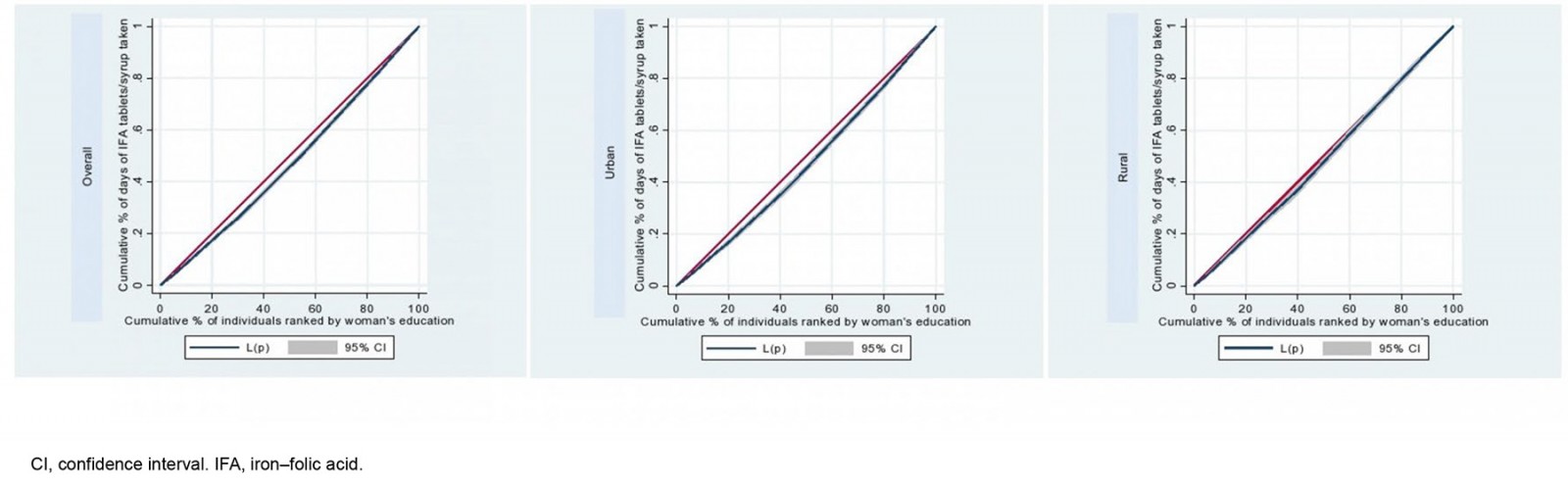

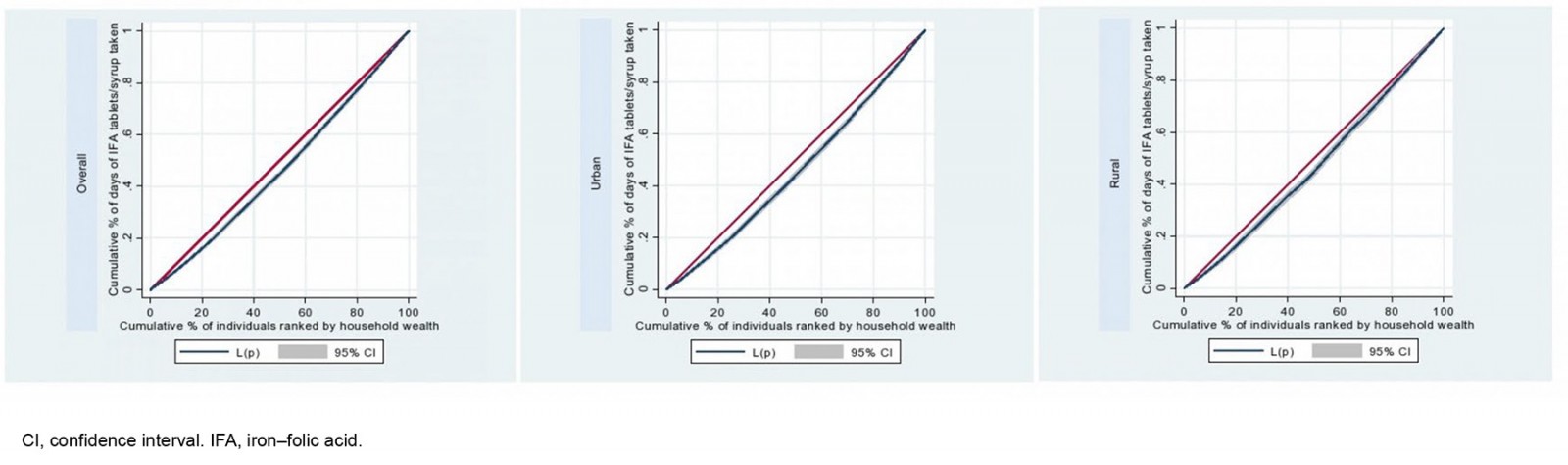

As shown in Table 4, the concentration indices for antenatal IFAS adherence, ranked by the woman’s education, were estimated at 0.102 (standard error (SE) 0.013, p<0.001) overall in both settings and 0.132 (SE 0.018, p<0.001) in women living in urban areas. The positive value of concentration indices indicates that educated women had higher adherence to antenatal IFAS. Nevertheless, there was a non-significant concentration of IFAS uptake among the more highly educated population in rural areas (p=0.126). Similarly, the positive value of concentration indices ranked by household wealth suggests that women from richer families had greater adherence to antenatal IFAS in all locations.

Figures 3 and 4 present the concentration curves for IFAS adherence among women aged 15–49 years, ranked by woman’s education and household wealth, respectively. As illustrated, all concentration curves lie below the line of equality, confirming that the percentage of IFAS adherence is greater in women with higher education and in wealthier households. It means that there were pro-educated and pro-rich inequalities in the adherence to IFAS. The greater the degree of disparity, the further the curves depart from the line of equality. However, following the results from Table 4, the concentration curve for IFAS adherence ranked by woman’s education in rural areas does not show substantial inequality (Fig3).

Table 4: Wagstaff normalized concentration index of antenatal iron–folic acid supplementation adherence by woman’s education and household wealth), based on data from 2017 Indonesia Demographic and Health Survey

Figure 3: Concentration curves of antenatal iron–folic acid supplementation adherence ranked by woman’s education overall, and in urban and rural areas, based on data from 2017 Indonesia Demographic and Health Survey.

Figure 3: Concentration curves of antenatal iron–folic acid supplementation adherence ranked by woman’s education overall, and in urban and rural areas, based on data from 2017 Indonesia Demographic and Health Survey.

Figure 4: Concentration curves of antenatal iron–folic acid supplementation adherence ranked by household wealth overall, and in urban and rural areas, based on data from 2017 Indonesia Demographic and Health Survey.

Figure 4: Concentration curves of antenatal iron–folic acid supplementation adherence ranked by household wealth overall, and in urban and rural areas, based on data from 2017 Indonesia Demographic and Health Survey.

Discussion

The present study examined social determinants and socioeconomic inequalities in adherence to IFAS in 12 455 Indonesian women aged 15–49 years with a child born in the 5 years preceding the 2017 IDHS. The current analysis reported approximately half of these women took daily IFAS for a minimum of 90 days. Adherence to at least 90 days of IFAS was linked to maternal age, access to the internet, frequency of antenatal care visits and geographic location. Moreover, the proportion of women with adherence to IFAS was more concentrated among educated women and in wealthier households.

Woman’s age was significantly associated with adherence to IFAS. This finding aligned with previous studies conducted in Ethiopia, Indonesia, and other low- and middle-income countries in Asia, Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean where the odds of adherence were higher among older women28,35,42. Older women had a higher risk of anaemia or iron deficiencies; therefore, they were more compliant in taking IFAS during pregnancy43 and particularly being targeted by health workers during the anaemia prevention program28. Older women tend to have better knowledge and awareness about IFAS importance21,44. While these findings support the need for targeted IFAS to specific vulnerable groups, it is also important to note that IFAS should cover all pregnant women across the nation to reduce pregnancy anaemia.

Maternal weekly access to the internet was also related to IFAS adherence. Following previous studies, the internet has become a valuable tool for accessing information, including about IFAS45,46. Also, internet access could provide opportunities to connect with online communities and support groups who had similar concerns, including sharing personal experiences and emotional support for women46. Thus, internet-based education can be an alternative to delivering information on pregnancy nutrition and health, including anaemia and IFAS.

The present study indicated a significant relationship between the husband’s education and IFAS adherence, particularly for those men with higher education overall and in urban areas. Our result was in line with previous research suggesting that husbands with low educational attainment were a predictor for non-utilization of IFAS24. Husbands with better education tend to understand pregnancy risks and be more engaged with pregnancy health47. Nevertheless, we found no significant association between the husband’s education at all levels and IFAS adherence in rural areas. While knowledge can be gained from various sources, our findings highlight the need for community-based education for husbands. Thus, involving husbands in women’s nutrition and health programs, including IFAS, will likely enhance the program’s impact.

Following previous studies15,20,35, this study found that antenatal care for at least four visits was significantly linked to IFAS adherence. The possible reason is that IFAS is distributed during the antenatal visits. Those who did not come for antenatal care might not receive IFAS. Additionally, those who attended antenatal care for at least four visits may have done so because they were health conscious, and knew the importance of adhering to IFAS. Another reason for this is that health providers would advise pregnant women about IFAS during their antenatal visits, which may enhance their knowledge and awareness, thus adhering to IFAS and better managing its side effects35,42. Therefore, increasing the coverage and quality of antenatal care is required to improve pregnant women’s adherence to IFAS.

Living in Java and Bali was associated with the likelihood of IFAS adherence. Women who lived in the Java and Bali regions were more advantaged than those living in other regions. The explanation could be that the coverage of antenatal care services in Java and Bali was higher than the national coverage7 and among the highest of all other regions in Indonesia7,48. Java and Bali have also been recognized for their quality health facilities, infrastructure and health professionals49. Thus, despite the widely spread geographic areas in the country, healthcare equity should be implemented across Indonesia to reduce the burden of accessing quality healthcare services.

Although there were no significant associations between woman’s education and household wealth and adherence to IFAS, our study suggests interaction effects between woman’s education and household wealth and place of residence, indicating socioeconomic inequalities in IFAS in rural and urban areas. Moreover, while the concentration indices indicated education- and wealth-related inequalities in IFAS, the magnitude of inequalities between rural and urban was different. This could be because women’s education in rural areas tends to be more homogenous as shown in our interaction analyses, thus having similar knowledge and adherence to IFAS. Supporting this finding, Statistics of Indonesia has reported that the proportion of the population with primary education was similar between rural (96.9%) and urban (98.6%) areas, but differed in high school education, with 55.5% in rural and 73.9% in urban areas50. Thus, enhancing household economic status may reduce the gap in IFAS adherence between rural and urban areas of Indonesia. While there is no significant relationship between the woman’s education and IFAS adherence in rural areas, educating women about the importance of IFAS and overall pregnancy health and nutrition should be of importance. Such interventions should not be limited to formal education, but also be in informal educational platforms, including education based in health facilities, communities, and through media.

To our knowledge, this is the first study in Indonesia to estimate socioeconomic inequalities in IFAS. While existing international studies assessed inequalities in IFAS adherence using analysis of determinants23,27, we performed specific inequality analysis using concentration indices by woman’s education and household wealth to quantify the socioeconomic inequality. Statistical analyses throughout this study were adjusted for the IDHS survey design, including sampling weight, clustering and stratification. The use of various social determinants of IFAS adherence is useful for identifying the immediate and root causes of IFAS. However, the nature of this cross-sectional survey did not allow us to draw a causal inference. Also, this study might have recall bias since the number of days of IFAS consumption was purely based on the women’s recall.

Conclusion

Overall adherence to antenatal IFAS was associated with various factors: the women (age, education, occupation, birth number, internet access, involvement in decision-making), household (husband’s education, household wealth), health care (antenatal care visit) and community (place of residence, geographic region). There were also pro-educated and pro-rich inequalities in overall adherence to antenatal IFAS. Nevertheless, there was no significant association between woman’s education and adherence to antenatal IFAS and no education-related disparity in adherence to antenatal IFAS among women in rural areas. Thus, programs and interventions to improve adherence to IFAS should target women of reproductive age and their families, particularly those from socioeconomically disadvantaged groups residing in rural areas. Such efforts may include enhancing information, education and counselling during antenatal care, and improving the use of the internet and online social media for health information.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Demographic and Health Survey for providing access to the 2017 Indonesia Demographic and Health Survey data for this study.

Funding

No funding was received for this research

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare for this study.

References

You might also be interested in:

2021 - Workplace locations of 2011–2017 Northern Territory Medical Program graduates

2018 - Promoting delayed umbilical cord clamping: an educational intervention in a rural hospital