Introduction

Australian rural volunteer ambulance officers (VAOs) support communities by responding to medical or traumatic emergencies1-3. Ambulance services within Australia frequently use a combination of first responders, VAOs, registered paramedics, critical care/extended care paramedics and aeromedical rescue services4. Within metropolitan regions, paramedics provide emergency care, whereas in rural regions there may be a blended service of paramedics and VAOs or a complete VAO model4. Occasionally, VAOs attend labouring patients progressing to birth. Births occurring in an unplanned location are referred to as out-of-hospital births (OOHBs) or births-before-arrival (BBA)5,6. In 2021, Australian OOHBs accounted for 0.8% (n=1856) of births, up from 0.4% in 20167.

Many maternity units have been centralised to larger regional centres, impacting accessibility of antenatal care for rural and remote communities8,9. Drive time to maternity services exceeds 30 minutes for 17% of birth parents in regional areas and 60% in remote regions9. A systematic review of obstetric services suggests longer travel times may be associated with increased risk of OOHBs and life-threatening complications such as postpartum haemorrhage and neonatal mortality10.

Recently, particularly following the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, Australian birth parents are reconsidering birth locations, with more people opting for homebirths11. Given the shortage of midwifery care for home birthing, some birth parents may consider a planned freebirth if a midwife is unavailable; a freebirth occurs when there is no attending healthcare professional11-13.

OOHBs and freebirths are at increased risk of adverse outcomes compared to planned home births or hospital births5,6. Research suggests ~12% of OOHBs result in complications, rising to ~27% when considering all intrapartum cases. Unsurprisingly, complications have improved outcomes if a skilled clinician is present; however, access to skilled maternity care can be limited in regional areas14,15.

Registered paramedics perceive a lack of adequate training, exposure and confidence with managing OOHBs, and often associate OOHBs with feelings of stress and anxiety16-18. Other documented challenges for paramedics include geographic distance to definitive care, uncontrolled scenes, limited access to clinical support for advice and poor communication16-18. If registered paramedics feel challenged attending OOHBs, it is conceivable that less-qualified VAOs may experience similar or more profound challenges. Research targeting VAO perceptions of challenges associated with OOHBs is limited. The present study aimed to determine VAO (and synonymous roles) perceptions of training, experience and confidence regarding management of unplanned OOHBs.

Methods

Recruitment

VAOs were recruited using purposive and convenience sampling19, using personal contacts and snowball sampling. An email was sent to potential participants, informing them of the study purpose, eligibility criteria (aged ≥18 years, an Australian resident, a current or recently retired (<3 months) rural VAO) and requesting they respond to the researcher, who would follow up with further information. Participants signed consent forms prior to interview sessions.

Setting

Australia encompasses approximately 7.7 million square kilometres, with 28% of Australians living in rural and remote communities20,21. Most tertiary maternity hospitals are located in regional or metropolitan areas. Approximately 130 rural maternity services have closed since 1995 due to workforce issues and service centralisation8.

Data collection

Focus groups and interviews were scheduled according to participant availability. Sessions were conducted by videoconference or telephone. All interviews were conducted by the same researcher (MH).

Interviews utilised a semi-structured interview guide (supplementary material) exploring VAO OOHB training, exposure, experience, perceived confidence, skills decay and knowledge gaps. The interview guide was developed in consultation with seven paramedics and midwives and was piloted with two paramedics for face and content validity. Interviews and focus groups were conducted until theoretical sufficiency was achieved22.

Data analyses

Discussions were digitally recorded, transcribed verbatim, and uploaded to Microsoft Excel for manual analyses. Transcriptions were de-identified and participants randomly assigned pseudonyms to retain anonymity.

An interpretivist paradigm was utilised whereby a social reality is not singular – rather, understanding is gained from an individual’s subjective experiences. This was deemed appropriate given each participant’s subjective experience may differ22,23. As discussions were of an exploratory nature, reflexive thematic analyses and semantic coding were utilised22. An iterative approach was undertaken to code transcripts whereby initial open coding occurred, grouping similar participant responses together. From these responses selective coding then formed thematic categories, then into overarching core categories. Credibility was achieved through member checking (MH, BM) to ensure participant validation. This allowed for a co-construction of data, providing an opportunity to engage with and add to the data as it was interpreted.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the Edith Cowan University Human Research Ethics Committee (#2020-02390).

Results

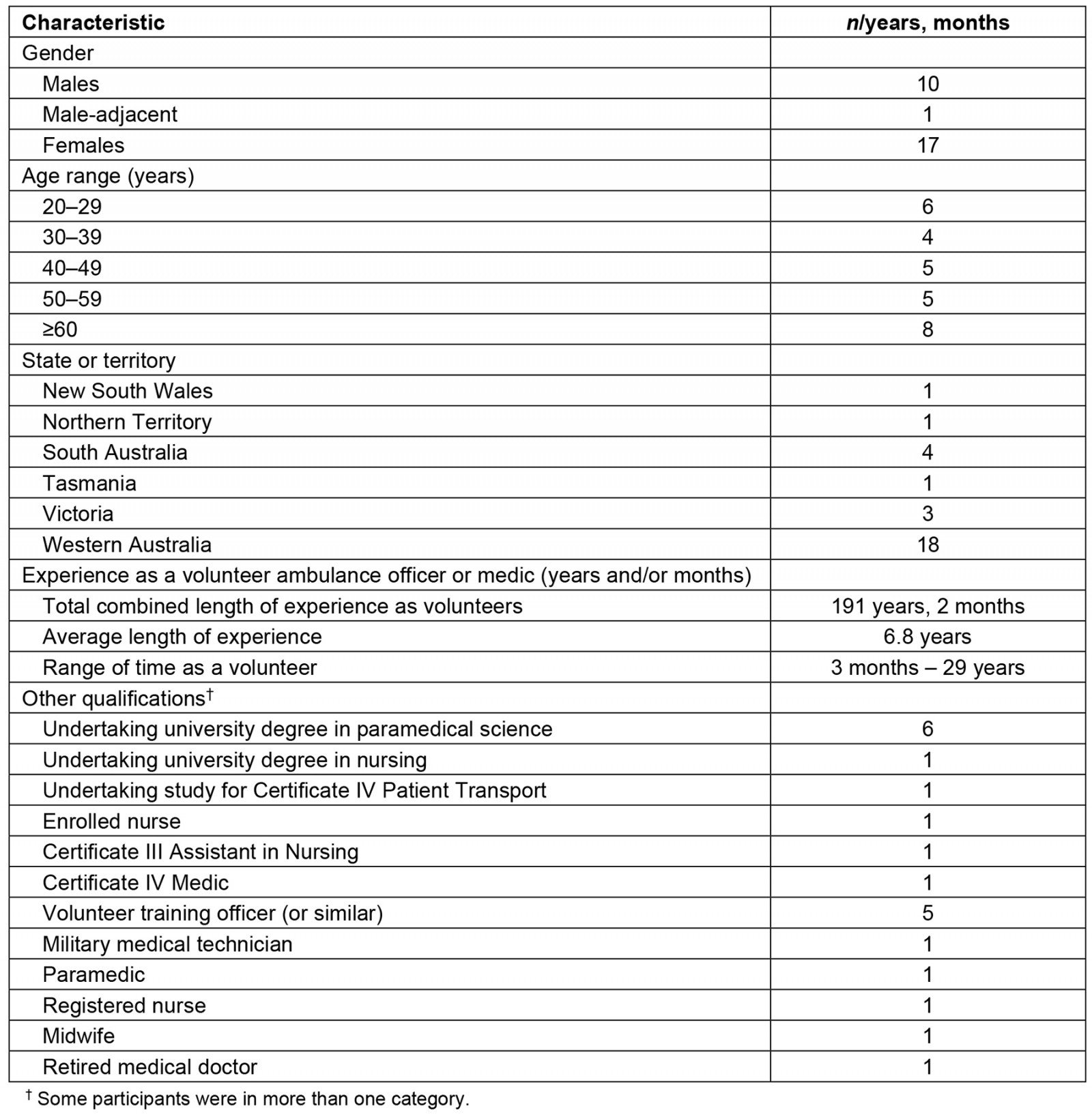

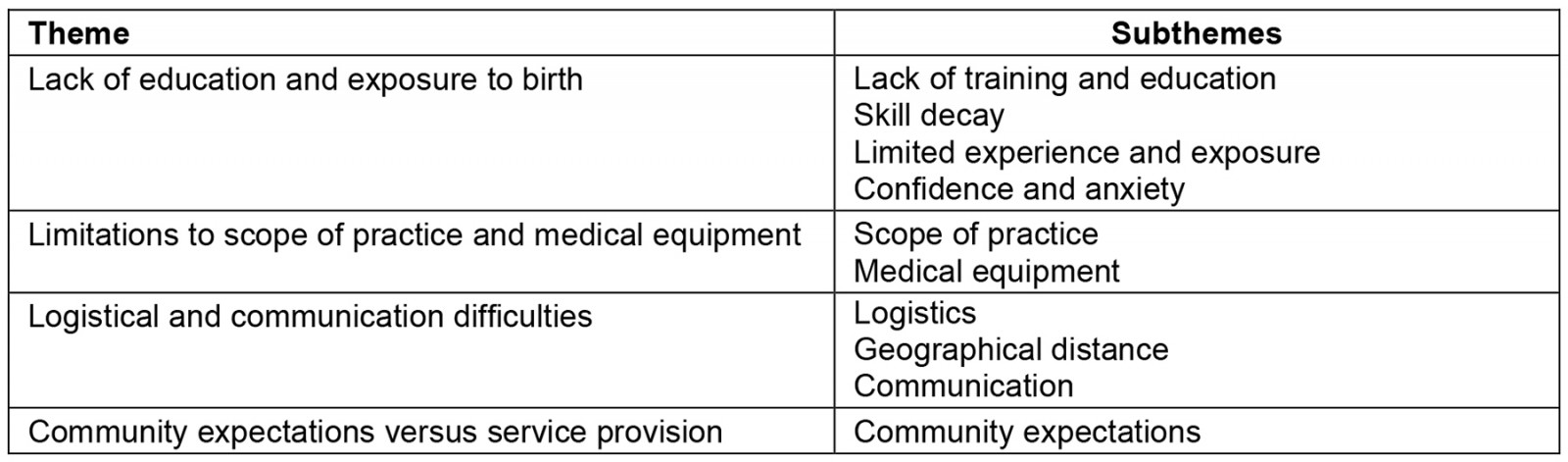

Four focus groups and 15 one-on-one interviews were undertaken with 28 participants, averaging 51 minutes in length, between September 2021 and June 2023. Research commenced using focus groups; however, a pragmatic decision was made to continue using interviews following the first four focus groups, due to time zone complexities, shift work obligations and the impact of Sars-CoV-2 on attendance. Six Australian states and territories were represented from seven jurisdictional ambulance services. Table 1 provides participant demographic data. Thematic analysis of the transcripts resulted in four major themes and subthemes (Table 2).

Table 1: Volunteer ambulance officer participant demographics

Table 2: Themes and subthemes identified from volunteer ambulance officer interviews regarding out-of-hospital births, Australia, September 2021 – June 2023

Lack of education and exposure to birth

Lack of training and education: Twenty-one VAOs suggested they had previously completed some form of obstetrics training. Seven participants had not undergone any obstetrics training. Six of these seven theorised this may have been because they were relatively new to the VAO role (<2 years). Participants reported that generally their organisations provided obstetrics training annually or two-yearly with training lasting approximately 2 hours. If a participant missed training, a catch-up session may be provided later in the year; however, often the topic was not revisited until the next official training session. One participant had not undertaken any obstetrics training in the previous 5 years. Several VAOs had access to birthing and neonate mannequins for practice while about one in four participants did not.

Participants described obstetrics training as primarily focusing on a ‘normal birth’ with a brief overview of potential complications via a didactic lecture or practical workshop. Many participants described feeling underprepared to manage potential complications.

I would have done my EMT [emergency medical technician] course probably four years ago, and it's a probably an hour-long module, and we do a PowerPoint. We watch a birth as part of it talking through the stages of labour and what not, and we go through a couple of very basic [births]… if baby gets stuck, this is – and realistically, if baby doesn't progress, 'call [for help]' is essentially our level of training. And then we just have one go at catching a baby out of a manikin and doing the like, you know, the ‘check the airway’, the ‘rubbing the baby’, now do we need to give them respirations or start CPR [cardiopulmonary resuscitation] and their Apgar score, and then we were passed on our course and sent on our way. (participant 10)

Many VAOs reported training was delivered in their region by other VAOs, sometimes supplemented with online resources. Participants expressed concern over their volunteer trainers’ limited experience and lack of obstetric knowledge.

… we've never been midwives. We've never, you know, had mass exposure to any of those situations … But you know, all of the extra training someone may have is all only as good as the person who's training them, who actually might have no more experience or not much more knowledge than they do. (participant 10)

Obstetrics medical terminology was a concern for a few participants while communicating with patients and hospital staff. Participants described feeling less informed than parents, making them feel less knowledgeable than their patients.

If mum’s had some kind of antenatal care, she's probably going to know more than us, you know, about different bits and pieces. You know I don't want to look like an idiot going, ‘What's this? What's that?’ (participant 15)

Some participants independently sought further training to manage perceived deficits in their own obstetric knowledge, reporting they were in discussions to try to establish a hospital-based placement for themselves and other volunteers to increase exposure to birthing. One participant had undertaken self-directed obstetrics continuing professional development training. Six participants were completing obstetrics training during their undergraduate paramedicine degree. These participants advised the additional knowledge gained via their degree would undoubtedly be useful for early recognition of complications. Five participants had additional obstetrics training as part of another qualification.

Skill decay: Knowledge and skill decay was a concern for all participants. They felt OOHBs were rare, with training occurring infrequently and described as ‘inadequate’.

When we do the training sessions on it, and we tend to do it once per year for maternity, and it tends to get skipped over. (participant 18)

One participant who had undertaken biannual obstetrics training only a week prior described practices and recommendations that lacked evidence in actual practice, adding to the concern of inexperienced trainers delivering sessions.

Not until the baby’s head’s coming out and then we are just able to guide it. So, if the placenta came first for example, you'd have to be able to push it back in and hold it in and hopefully until we got to the hospital. (participant 7)

Limited experience and exposure: Five participants reported exposure to birthing during their volunteer career. This excluded exposure to birthing in other career pathways, such as midwifery. Participant 12 attended two uncomplicated OOHBs; the participant assumed the role of accoucheur (one who assists with birthing)24 for one neonate, which birthed on ambulance arrival, while the second birth occurred before the ambulance arrived. Participant 4 assisted emergency department nurses with a precipitous birth following transportation to the local hospital. Participant 28 arrived post-birth and recalled:

Mum was good. Baby, I really can't remember much; the baby wasn't well. It was an RFDS [Royal Flying Doctor Service] callout, so it wasn't obviously too well. (participant 28)

However, participant 28 felt there were ‘no major complications’.

Participant 24, a VAO who had some exposure to birthing during their career, attended one planned homebirth with fatal complications for the neonate. They described the situation as ‘absolutely just the worst night’. Participant 27 reported attending two OOHBs; the first was a precipitous premature birth without complications, with the neonate arriving just before the ambulance. Paramedics arrived minutes later to take over management. The second case was a known stillbirth due to placenta praevia, resulting in a massive postpartum haemorrhage.

I learnt a lot from that job simply because I chose to do a clinical audit on it afterwards, because I don't think I even heard of the condition prior to going to this job. (participant 27)

Many participants recalled attending call-outs for ‘imminent births’, transporting labouring patients to hospital before birth occurred. Rural VAOs also transferred labouring patients from small rural hospitals to larger regional hospitals with additional obstetric facilities, which always involved a hospital midwife attending the patient during transport. Several participants reported being aware of VAOs who avoided responding to ‘imminent birth’ call-outs, with one participant acknowledging she preferred not to attend these types of cases.

And the first thing I ever hear when a call comes through and they say: ‘imminent childbirth’, so you can see the ambulance officers go ‘oh God, oh great’… it's something we don't want to go to. (participant 12)

Confidence and anxiety: Given the infrequency of actual birth experience, participants were asked how they think they would feel attending an OOHB. Most participants indicated they lacked confidence regarding managing OOHB situations, while some VAOs stated their level of confidence would partially be dependent on how experienced their partner was.

This is the thing that scares the heck out of both paramedics and volunteers … little bubbies are the ones who probably do scare me the most, an adult’s not a problem. (participant 18)

I'd like to think that if it was uncomplicated and a normal birth then I'd be fine with it; 'cause it’s a natural thing at the end of the day. But I think just that sense of responsibility ... if it wasn't, you know, I think I'd be quite nervous to be honest. Yeah, I mean I'd be able to offer reassurance because I'm actually a hypnobirthing practitioner, so I know that making people relaxed is part of that; I'm not sure when it came down to it. (participant 6)

Of those few participants who felt more confident, many had additional clinical qualifications. Conversely, some inexperienced VAOs expressed confidence despite minimal experience or exposure and reported they would rely on their standard systematic decision-making assessment and advanced first-aid management.

… I'm quite fresh into the industry … I've got kids of my own, so I am a little bit confident. However, my knowledge doesn't match my confidence. (participant 17)

Most participants explained they would feel anxious attending an OOHB. The level of anxiety was often dependent on their birthing experience and training. While a ‘normal uncomplicated birth’ was described as ‘still concerning’, participants were more anxious or apprehensive about the possibility of complications – 'you don’t know what you don’t know' (participant 25) – especially in rural locations. One participant explained:

We aren't provided the training really, to at least just really have a good understanding of what could happen … [I] wasn't confident that I'd [pick up early] on things that would make it a priority one and time critical too, you know, and in [the] country minutes matter. (participant 10)

Limitations to scope of practice and medical equipment

Scope of practice: All participants described the VAO scope of practice as restricted to accoucheur. If complications occurred, all VAOs suggested their clinical practice guidelines advise them to request assistance from a senior support officer and/or provide rapid transportation to definitive care. However, there was considerable apprehension regarding availability of senior support officers in regional areas.

… a large percentage of country [service redacted] there is no clinical support, and they [volunteers] don’t really have the skillset to manage it … even if they have a wider skillset than some of the other states, it’s not adequate. (participant 24)

One participant, who was also a qualified midwife, advised she was confined to her VAO scope of practice when working as a volunteer. When asked about the discrepancy between her midwifery qualifications and volunteer scope of practice, her response was:

There's always a fine line that I know I'm not allowed to jump over. (participant 9)

Some participants reported knowing volunteers who left their respective service out of frustration due to scope-of-practice limitations.

... she was actually a nurse ... she left because she couldn't practice, she was so restricted with being a volunteer … she thought this is wasting her time, ‘I can't do anything.' (participant 22)

Another VAO advised he was able to contact his local hospital to receive (for example) authority to cannulate and provide intravenous fluids under his nursing scope of practice in an emergency.

Participants studying a paramedicine degree frequently remarked they had skills that were not able to be utilised as a volunteer, as it was outside their VAO scope of practice.

Legally I'm allowed to give morphine and IVs [intravenous administration] and cannulate, but as a volunteer I'm restricted to what [service redacted] allows me to do, which is next to nothing; like give them a green whistle [for pain relief], hope for the best. (participant 3)

Medical equipment: Medical equipment suggested to be available to VAOs varied, even within the same ambulance service. Most VAOs reported a very limited obstetrics kit was available to them, which increased their anxiety.

It was only when I did my training I realised our ambulance didn't even have any towels in the van to wrap a baby in. (participant 2)

One VAO advised that her region was equipped with neonate sphygmomanometer cuffs and pulse oximetry tapes, which was not typical in other regions. Some volunteer stations were also trialling tranexamic acid for postpartum haemorrhage.

Logistical and communication difficulties

Logistics: Participants described the lack of skill mix, age and inexperience of VAOs in rural locations and how this sometimes caused complications.

Having a backup volunteer who’s a youth who may have zero to no experience or may even be, you know, just beyond observer point. You know there are a whole bunch of logistics in the country that are super scary with high level emergency. (participant 3)

Participants also commented on the lack of maternity services within their jurisdiction, necessitating bypassing rural hospitals and travelling to regional hospitals. For complicated cases, aeromedical retrieval was an option. One participant reported a situation where the RFDS was required for a complex case; however, due to fog, the retrieval could not occur, and the regional hospital had to manage the situation despite inadequate resourcing.

I did find an obstetrician in [town redacted]. I said, ‘we are coming’, and she said ‘look we don't deal with thirty-two weekers’. And I said, ‘I know that’, but [airport redacted] was fogged in so they couldn't actually take off. The RFDS guy said, ‘look you're gonna have to get her to [town]’. (participant 9)

There were differences between states and territories regarding VAO ability to provide transport. Some VAOs were unable to transport unless accompanied by a paramedic.

We can drive the ambulance with the paramedics and patients, but we can't transport patients on their own. (participant 22)

Some had access to an ambulance but could not drive with lights and sirens, even with a paramedic onboard.

I can drive them, but I can only drive them at the speed limit. I can't go through red lights. (participant 18)

Other VAOs could drive with lights and sirens when appropriate. Some reported being restricted to a first response role: to attend, treat and advise on assistance required only. This meant if an incident occurred necessitating emergency transport to hospital, the VAO would attend the patient and call 000 for emergency ambulance assistance. One VAO explained he received a day’s driver training to drive the ambulances, while paramedics in his region received 2 weeks training, yet VAOs in this region attend the same incidents as paramedics.

Geographical distance: Closely linked to logistical concerns was the acknowledgement of the role of physical distance to definitive care in rural settings in patient management. Access to assistance in-person or online is not guaranteed in rural locations.

Distances can be massive, you know. Go out to somewhere quite a long way away. It can be through, over a really difficult pathway to get there. It can be really difficult to get people in and out of places and the distances that we have to travel, and we're out of phone range. So, it’s a very different sort of perspective on everything. (participant 12)

Many situations required aeromedical retrieval; however, this was not always available:

… we called for the helicopter, but the helicopter wasn't available. (participant 27)

Communication: Rural telecommunications and difficulties accessing adequate support when required were described extensively. All participants reported they would request backup for an OOHB, and/or contact clinical support from the ambulance service or hospital. A participant recounted an instance where two VAOs were required to manage a complex case and back-up was necessary.

… in the country minutes matter … we’re gonna have to send someone 5 minutes down the road to get radio signal which has improved [coverage]. But you know, in order to call for help, do we have 10 minutes of losing half our crew to send for help and then the extra 25 minutes for that help to arrive? Does this patient have that long? … Or do you actually use the bystander …? (participant 10)

Handovers to maternity staff at hospital was a concern for some VAOs. Midwives were sometimes critical of the information provided by VAOs and management of the patient. One VAO described an incident where she travelled 40 minutes to collect a patient, and then bypassed the local hospital to attend the regional hospital.

… getting to the hospital and the nurse is almost like yelling at us for being too casual about it, but it's like we've actually done everything in our training and we had no training to recognise if it is Braxton Hicks or if it is something more sinister. Or you know … we have no way of knowing, all we can do is get them in the ambulance and transport. (participant 10)

Community expectations versus service delivery

Community expectations were also discussed. Some VAOs felt the general public may not understand that the ambulance crew in rural locations may be primarily staffed by volunteers, and perceived the community expected the same level of competency from volunteers as they would from registered paramedics.

I think it's an expectation of you [from the community]. An ambulance arrives at their door, no matter what is happening, you expect them to be able to deal with it. That's what people's perception is when an ambulance arrives. So, Mum’s sitting there and Dad’s thinking, ‘oh, they’re going to deal with this’. (participant 12)

… other than looking at the epaulettes where it says paramedic versus ambulance officer … there's no markings on the vehicle that says volunteer or basic life support or anything like that … the public often has no idea. (participant 24)

Participants also thought that some birth parents were opting for a more ‘natural’ homebirth experience in some rural communities and may intentionally choose to freebirth with or without a doula in attendance. Participants felt birth parents may not realise the implications should complications occur.

… we have a high percentage of people that do homebirths, there's a lot of people into that sort of thing. So, they often, I've never been to a birth, but I know that they will have doulas, which I believe don't have any medical training, they're just there for emotional support; and sometimes I've had midwives … if they're the ones calling [for an ambulance], obviously it's gone pear shaped. … We do a lot of maternity transfers. (participant 15)

Travel to the hospital with this mum in agony and maybe in a dangerous situation, and you're really stuck – because the mum is obviously, and the father or whoever else is there [are saying], ‘Can you do something; you have to do something’ and you're in this situation of having to say ‘Well, no, I can't [do anything more].’ (participant 12)

Many participants felt they would not only need to keep the patient calm, but also themselves. One participant was particularly apprehensive regarding possible cultural challenges with childbirth where male VAOs may attend the case.

… a complicated birth of someone whose religion would not allow a male to attend that person … you know, we need to do and see things. (participant 14)

Participants agreed they felt unprepared for such a scenario and felt they were not taught adequately how to manage these situations and communicate with the families.

Participants also discussed the potential adverse physical and psychological impact on the patient(s), bystanders and themselves in the case of a traumatic birth. Most VAOs were apprehensive regarding management of neonatal or infant death, with no participant being comfortable managing such events. One VAO discussed the counselling services available to VAOs in her region for difficult cases.

Someone giving birth, it's one of those moments in life, it's all and everything for a mother, like it's [a] pretty daunting experience for everybody involved. And you don't want negative outcomes in childbirth, because that’s a bad thing, it's not something you are ever going to forget, is it? … So, when it does go wrong, that's out of the norm, and all [of a] sudden it's ‘holy shit’, I've been a part of this broken process. (participant 3)

… it's one of those ones that I think we probably underestimate the effect on the volunteers if we don't best prepare them … as a volunteer, you can get mentally scarred because of what you'll be doing. (participant 18)

There was also concern in regional areas that VAOs often know their patients due to living in a close-knit community. This could aid with clinician–patient communications due to previously established relationships. However, concern for psychological trauma was heightened, particularly concerning complications.

I've just seen it so many times that they ... it's their neighbour, friend, relative and they're the only option for prehospital help in those towns. (participant 24)

Discussion

This research determined that, among a sample of Australian VAOs, most lack confidence in responding to and managing OOHBs due to their limited education and training in and exposure to birthing, and have concerns regarding their fundamental skills and knowledge, especially pertaining to complications. Some VAOs may have misconceptions about their knowledge regarding birthing complications. Current practice often has a senior VAO providing training; it would seem prudent that a registered paramedic or midwife teach this specialist subject. Previous research concerning paramedic and volunteer roles in rural Australia reported continuing education and skills maintenance as an ongoing issue, particularly for rarely utilised skills25. The Rural Doctors Association discusses the need for rural healthcare professionals to be adequately trained in obstetrics care, especially given the possibility of OOHBs, and emergency retrieval and transport services should be dispatched expeditiously when required15.

Maternity services centralisation throughout Australia raises concerns for rural and remote communities, as regional hospitals may not be equipped to manage complex cases, necessitating aeromedical retrieval15. One study investigating aeromedical retrievals identified 3327 transfers concerning pregnancy, childbirth and puerperium26. Aeromedical retrieval is dependent on weather and aircraft availability, further complicating emergency obstetrics care27. Therefore, VAOs require additional support, training and exposure to aid management of obstetric emergencies adequately in rural and remote regions. It is acknowledged there is a shortage of registered clinicians in rural and remote regions of Australia4, highlighting the concern for VAOs who may be undertrained, lack exposure or experience knowledge and/or skill decay. In resource-limited regions there is no simple solution to the dilemma where the VAO scope of practice generally provides supportive care, yet more advanced skills may be required. Ensuring VAOs refresh their obstetrics skills frequently, are aware of potential ‘red flags’ for complications, and have strong interprofessional networks will enable VAOs to reach out for clinical support and advice early.

Appropriately coordinated multidisciplinary and inter-organisational training may prove beneficial in the rural and remote community to aid cross-professional learning and allow a deeper appreciation of roles within the rural healthcare system. Such sessions act as refresher training, scaffolding prior learning, and strengthen professional networks, working to reduce potential tension between disciplines. Interprofessional education between paramedics and nurses/midwives has historically proven beneficial by improving communication between disciplines, increasing understanding of roles and scope of practice, and improving handover interactions16,25,28,29.

Anxiety and occupational stress/trauma experienced by VAOs was top-of-mind for participants, with several factors, including inexperience and lack of specialist support, suggested to impact anxiety levels regarding OOHB call-outs. Research suggests paramedics experience mental health issues at a higher rate than the general population30, which may also apply to VAOs. Accessing mental health services remains housed in stigma31, therefore novel approaches are encouraged to reduce psychological harm and improve long-term wellbeing. A US study exploring stress and anxiety among volunteer emergency personnel identified being selective of which call-outs to attend as a popular coping strategy when lacking confidence with a particular case32. Our research also found VAOs may opt-out of responding to particular cases, potentially impacting local emergency response32,33.

Early recognition of complications can be critical in ensuring correct clinical pathways are chosen promptly to minimise adverse sequelae for OOHB cases. Skill and knowledge decay occurs rapidly; a performance decrease of more than 90% may transpire within a year of previous exposure for a specific skill34,35. O’Meara et al assert VAOs benefit from locally stationed paramedics providing VAO knowledge and skills training within their scope of practice26,36,37. VAO participants in this research indicated some regions had insufficient support from registered paramedics to aid with complex call-outs or provide additional training. According to recent data38, there is inequity in paramedic representation between Australian states and territories, varying from 46 to 99 paramedics per 100 000 people, with less than 2% of paramedics working in rural or remote locations38. This may impact VAO educational opportunities and access, with flow-on effects to patient care.

Anecdotally, the participants in this study said that birth parents in remote locations or high-risk births are usually advised to relocate to larger regional services or metropolitan areas to be closer to suitable obstetrics services when they are at about 36 weeks gestation, supported by research confirming maternity services are sometimes several hundreds of kilometres away8,39. While most birth parents are aware of relocation requirements, premature births and other obstetric emergencies may and do still occur prior to relocation while other birth parents may wish to ‘birth on country’40. Clarifying birth parent understanding of emergency ambulance services in the event of an emergency is an area requiring additional study. Rural ambulance services are frequently faced with long distances and difficult pathways to access patients, inevitably resulting in delays reaching definitive care41. In 2015, it was suggested rural physicians should also be incorporated into the pre-hospital care model, especially given many rural areas are serviced by VAOs who can only provide a basic level of care41. While our participants did sometimes indicate they could call a regional hospital for advice if their own clinical support officer was unavailable, no participant indicated a medical doctor was available in an emergency.

To support VAOs attending intrapartum cases, access to an obstetrics expert via telehealth is highly desirable. Areas with no mobile service further impede access to expertise42, leaving volunteers vulnerable and isolated when attending OOHBs. Alternatives may include a national on-call obstetrics hotline similar to PIPER (Paediatric Infant Perinatal Emergency Retrieval) in Victoria or Storc (State Obstetrics Referral Call) in Western Australia43,44, which provide obstetrics advice.

Rural communities’ understanding of the more limited roles and responsibilities of VAOs compared to paramedics may not be well understood and requires more research to comprehend the issue’s significance45. This is of increasing concern when considered alongside a trend of increasing OOHBs and freebirths11. Undiagnosed complications increase risk to both birth parent and neonate if an emergency should occur11. Birth parents may be unaware of the distances to definitive care.

Volunteer ambulance transport service delivery models are well established within rural Australia46,47; however, models may require adaptation to meet contemporary community needs. Recent research supports the emergence of alternative paramedic models of care in remote regions, many of which include extended care paramedics who provide more comprehensive care within the community and are not simply an emergency response clinician46. Additionally, VAOs must navigate the complexities of living within the community they serve and the associated impacts an adverse event would have. Ambulance services should ensure sufficient organisational and educational support is available to VAOs and build strong interdisciplinary and inter-organisational relations to strengthen community care25,32.

Limitations

This research collected data with a national sample of VAOs, excluding Queensland and the Australian Capital Territory. However, Australia’s Productivity Commission data for 2023 suggests our sample was representative of the Australian VAO population stratified using state and territory percentages, with Queensland documenting low numbers of VAOs, while ACT has no reported VAOs48. Further, participants self-selected into the research, possibly introducing selection bias.

Conclusion

VAOs in this study reported low confidence and exposure to birthing and felt undereducated on obstetrics. Challenges specific to rural environments were identified, including time and distance to definitive care, poor telecommunications and the limited ability to provide appropriate care should complications occur. Adequate clinical, educational and organisational support should be available to VAOs to ensure continuation of essential emergency services to Australian communities.

Funding

This research was undertaken with assistance from a PhD scholarship awarded as part of an Edith Cowan University Vice Chancellor’s Research Fellowship.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

You might also be interested in:

2022 - Telehealth use in rural and remote health practitioner education: an integrative review