Introduction

In Canada, approximately 1.8 million individuals identify as Indigenous, encompassing those of Inuit, Métis, and First Nations origin1. Indigenous Peoples’ history in Canada has been marked by systemic discrimination and institutional oppression enforced by the Canadian government, leading in intergenerational trauma2,3. The government’s actions, such as forcibly relocating Indigenous people, establishing residential schools, suppressing native languages, criminalizing cultural practices, and violating treaties, have been associated with adverse health outcomes among Indigenous populations, such as anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder2,4. Recognizing the historical context of colonization is critical in understanding the health disparities in Indigenous communities. The process of colonization has had long-lasting impacts on subsequent generations3. This increased vulnerability has also influenced parenting styles and children’s coping strategies, and increased their exposure to stressors (eg discrimination)5. Cultural trauma has resulted in higher rates of addiction, mental health challenges, and family violence, perpetuating the overall lower health of present-day generations6.

Indigenous youth are a priority within their communities, as they are recognized to be the future – the next generation of parents and leaders7. In line with the principle of the seventh generation, the vision of Indigenous Peoples places importance on environmental, economic, and health issues in the hope of ensuring a bright future for future generations, including children8. From this perspective, the health status of Indigenous youth is an integral aspect of their culture. However, they continually encounter significant challenges concerning their overall health and wellbeing9.

A systematic review was conducted to quantify the relationship between psychosocial factors and mental health in Indigenous children, and revealed that experiences of discrimination, family dynamics, substance abuse, and psychological traits (eg self-esteem) are factors associated with negative mental health outcomes10. A wellbeing survey conducted among New Brunswick students in grades 6–12 (2018–2019) found that Indigenous youth scored lower than their non-Indigenous peers on 49 of the 57 items related to mental health and substance use, indicating poorer mental wellbeing11. While it is known that geographic location also influences health status9,12, it has been reported that one in four First Nations youth living on reserve experience psychological distress linked to moderate to severe mental health issues13.

Health and wellbeing conceptions

The understanding of health within Indigenous communities is based on a holistic (also referred to as wholistic) approach. This perspective encompasses all aspects of wellbeing, including psychological, spiritual, emotional, and physical health, which are deeply integrated into the ways of life of Indigenous communities14. Guided by a (w)holistic worldview, Indigenous communities emphasize the importance of maintaining balance across these four dimensions15. Furthermore, spirituality holds a crucial role in the (w)holistic view of health, involving the use of traditional medicines, close relationships with Knowledge Keepers (Elders), and a unique connection to Mother Earth and nature16,17. The relationship with the land profoundly influences the cultural, spiritual, emotional, physical, and social aspects of individuals and communities18. In the traditional unceded territory of the Wolastoqiyik, the First Nations People follow the teachings of the medicine wheel, which symbolically represents the Earth and encompasses various concepts, such as the four cardinal directions (north, south, east, and west); the four seasons (summer, autumn, winter, and spring); the four elements (earth, water, fire, and air); and the four dimensions of health (physical, spiritual, emotional, and mental)19,20.

Moreover, all four dimensions of health are distinctly influenced by a wide range of social determinants of health that are often not well understood given that little is known about how they have adversely impacted and shaped Indigenous individuals’ health outcomes21. Social determinants of health are defined as ‘conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age and that, together, provide the freedom people need to live lives they value’22. These determinants can be classified as proximal, intermediate, and distal. Proximal social determinants of health are often used to explain social disparities (eg socioeconomic status, physical settings, and direct health-related behaviors)9. Healthcare systems, education systems, social support, and cultural continuity have been classified as intermediate determinants, while colonization and racism have been classified as distal9,23. Therefore, it is crucial to understand the importance of social determinants of health, as a more efficient approach to interventions involves implementing broader interventions that target the inequities present in social determinants of health21. Through this study, we explored the impact of social determinants of health in explaining differences among various First Nations groups, thereby offering insights into the importance of having culturally relevant measures that consider local differences when assessing Indigenous children’s health and wellbeing.

Indigenous child health measure

Indigenous organizations and community health directors consistently highlight the lack of comprehensive data and the urgent requirement for measures to bridge the gap in health assessment and health disparities among Indigenous youth24-26. In a study by Young et al (2013), it was established that cross-culturally adapting an existing measure was not possible given the (w)holistic nature of the health of Indigenous populations27. As a response, they developed the Aaniish Naa Gegii: Child Health and Well-being Measure (ACHWM), which was specifically designed to align with the values and beliefs of Indigenous Peoples27.

The ACHWM is a measure that was co-created with and for Indigenous children from the Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory in northern Ontario. A total of 38 Indigenous children and youth actively took part in focus groups to identify concepts of health and wellbeing, which formed the basis of the initial version of the questionnaire27. The measure aims to provide a (w)holistic perspective on wellbeing that goes beyond health and considers all four dimensions of the medicine wheel. The PedsQL (Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory) Measurement Model was used to validate the ACHWM, offering a reference score for comparison. Despite the PedsQL’s reliability and validity for children aged 8–18 years, it does not fully account for the specific needs of Indigenous children28. This emphasizes the importance of culturally relevant assessment tools. Thus, the ACHWM measure is also reliable, sensitive, and facilitates self-assessment of health and wellbeing from the perspective of Indigenous children aged 8–18 years29.

Current study

While many First Nations communities in Canada share the same general concepts of (w)holistic health represented in the medicine wheel, there are still important cultural distinctions within each community. This emphasizes the importance of adapting the ACHWM to local context, ensuring that the vocabulary used in the measure is well understood and used by children in the specific community.

As residents of a French-speaking community, Wolastoqiyik children are exposed to various explanatory factors that contribute to specific cultural distinctions. These factors, such as differences in cultural knowledge and identity, are influenced by the strong presence of Francophone culture in their social setting. This sets them apart from other First Nations children. Similar to Métis children involved in an earlier cultural adaptation study30, Wolastoqiyik children have limited opportunities to gain knowledge about Indigenous culture due to the dominant presence of European-Canadian culture. Moreover, as most of these children are bilingual and attend schools in urban Francophone settings, they receive education primarily in French, which also sets them apart from First Nations children in previous ACHWM studies, who attended schools within their own communities27. Considering these differences, the French First Nations version of the ACHWM served as a starting point for this adaptation. To culturally adapt the ACHWM questionnaire for the children of this community, the study aimed to address two research questions:

- Are the French First Nations ACHWM questions relevant and applicable to Wolastoqiyik children and their caregivers?

- What revisions are needed to ensure that the questions are clearly understood and culturally appropriate for Wolastoqiyik children and their caregivers?

Methods

Participants

Recruitment was done through a community–university research team collaboration, during which the health committee directed the research team to eligible participants, with whom a member of the team contacted parents or caregivers by telephone. To ensure participant confidentiality, personal information was protected by the director of community health services, with only one member of the research team permitted access to participants' names and contact information, and authorized to make telephone calls to participants. A study sample of nine bilingual children aged 8–16 years (4 girls, 5 boys; mean age 11.6 years), two caregivers, and a community Elder, were recruited for a total of 12 individuals who identified as members or residents of the Madawaska Maliseet First Nation located on the traditional unceded territory of the Wolastoqiyik. In light of this community-focused study, the sample size was based on the needs and accessibility of the children within the community. Among the participants, six children, one caregiver, and an Elder were members and residents of the community, and three children and one caregiver were members of the community but registered as off-reserve.

Measure

The ACHWM is a sensitive and reliable culturally appropriate measure that facilitates self-assessments of health and wellbeing from the perspective of Indigenous children aged 8–18 years29. The questionnaire includes 62 questions measured on a five-category scale (‘never’, ‘rarely’, ‘sometimes’, ‘often’, and ‘always’) with three open-ended questions. Based on the medicine wheel, the ACHWM generates scores on the four quadrants of health: physical (eg being in good condition), emotional (eg laughing and having fun), mental (eg success in school), and spiritual (eg knowledge of traditional language), as well as an overall score that offers a (w)holistic picture of the health of Indigenous children. The calculated scores range from 0 to 100, and higher results indicate better health. To date, the ACHWM has been translated into English and French versions for First Nations, Inuit, and Métis children30 as well as versions for children-in-care31. This current adaptation was based on the French First Nations version.

Procedure

The partnership with the Wolastoqiyik community was built through a process of consultation with the chief, community council, and social workers. Specifically, community partners played a key role in guiding the project and introducing it to potential participants. In addition, a member of the community council was part of the study team. The initial step involved assessing the relevance of the ACHWM questions to Wolastoqiyik children and their caregivers. Input from five community experts was gathered through informal discussions, leading to an agreement on the content's relevance. Once it was determined that the content was appropriate for children, the adaptation of the French First Nations version of the ACHWM took place. Interviews were conducted with the children who had been previously contacted by a member of the research team.

In our second step, the goal was to determine the revisions required to culturally adapt this measure. We obtained written consent from all participants as well from their parents to be interviewed about the content of the ACHWM. In addition, each child gave verbal consent to participate in the study at the start of each interview. A cognitive debriefing-based qualitative method was employed to assess the questionnaire's content with parents and children. This method has been utilized in prior research involving the ACHWM27,32. As described by Jobe (2006), this process involved one-on-one interviews to assess the effectiveness of the questionnaire32. In particular, we used a think-aloud technique as well as probe questions to gain a comprehensive understanding of the children’s interpretations of the questions. For instance, participants were asked to elaborate on their understanding of different cultural terms or to share personal experiences. Each interview lasted approximately 45 to 60 minutes and took place in a private room at the community health centre in the presence of two members of the research team. The two investigators met with each participant individually and went through the 62 questions of the ACHWM. One asked the child to read and think out loud, and asked simple questions to probe for their understanding (eg ‘Can you give me an example of when you felt this way before?’), while the other took notes of the information reported. Caregivers had the option to participate in a separate interview in which their task was to review each question stated and discuss the content of the questionnaire. In addition, to ensure that all the questions were properly assessed, the questions were asked in a staggered fashion to avoid assessment fatigue. For example, the first child started with the first question and proceeded with the pre-established order of the questionnaire. The next child started at question 11. Any time that participants had trouble (eg with the terms being used, the answer choices, or the phrasing of the questions), these were noted along with suggestions, and revisions were considered for subsequent interviews so that common problems could be solved. Items were revised when at least two children reported a similar potential solution for the same item. During this iterative process, solutions were implemented and tested on subsequent participants.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for this study protocol was obtained from the Research Ethics Board at the Université de Moncton (reference number # 2223-004). Both verbal and written informed consent were obtained from all participants and their legal guardian(s). All procedures were carried out in accordance with all applicable guidelines and regulations.

Results

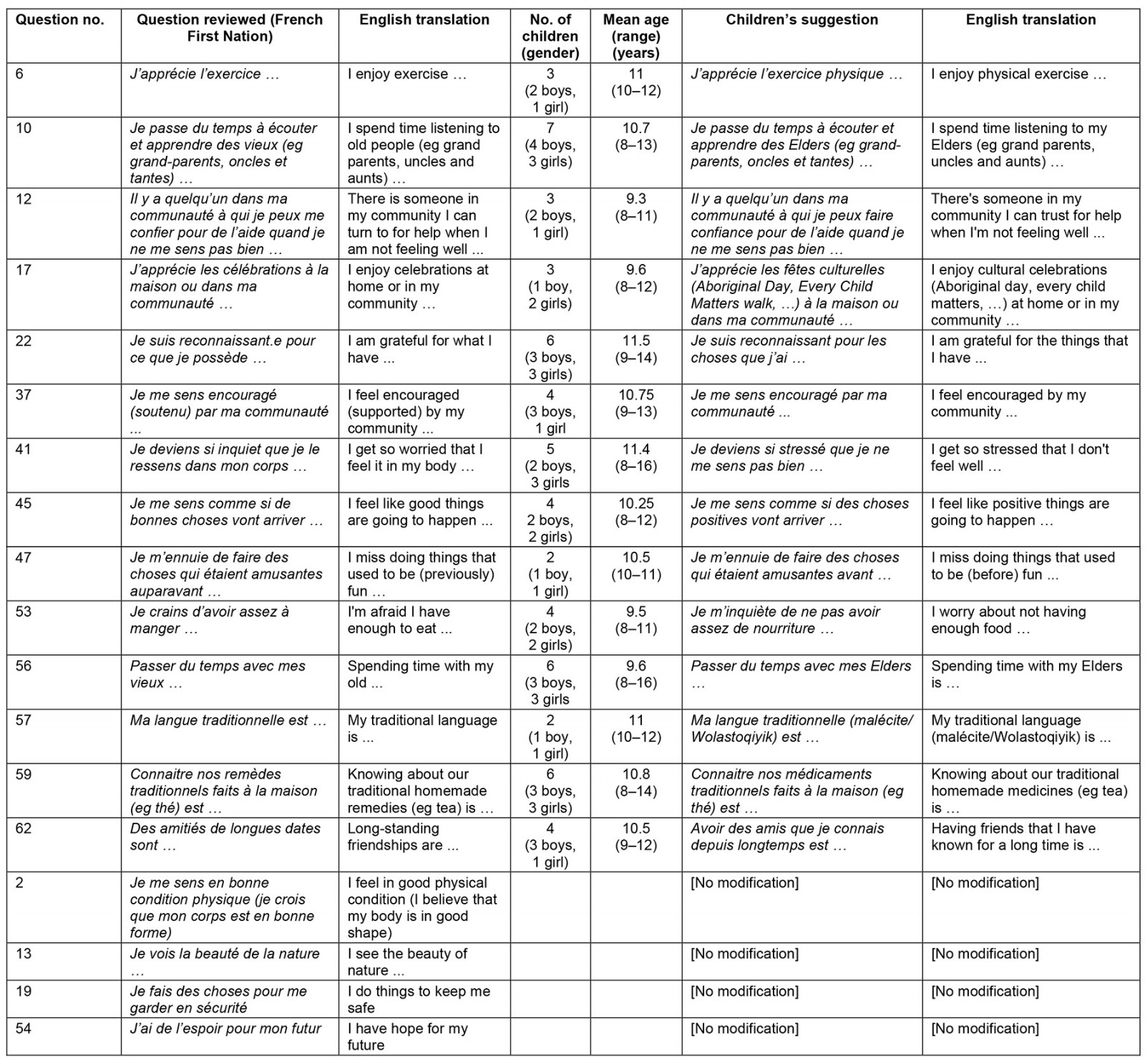

A total of 12 interviews were carried out. Following the interviews, 18 questions were identified as inconsistent with the Wolastoqiyik culture as identified by several participants. The questions requiring adaptation, as well as the suggestions made by the children during this step, are presented in Table 1. Although two caregivers participated in the study, their suggestions were used only to verify and support the children’s answers. Only the children’s suggestions were analyzed in depth given the aim of this research to use terminology that they knew and understood27. To verify the relevance of the suggestions reported by the children, the recommendations of the first participants were then proposed to subsequent children. In this way, it was possible to modify 14 questions, considering the information reported during the interviews. However, although at least two children reported an opportunity for improvement with four other questions, a subsequent analysis allowed us to conclude that a greater number of children were satisfied with the original wording, so the statements remained unchanged. The interviewed children did not recommend eliminating or adding any questions.

Table 1: Reviewed questions from the French First Nation version of the Aaniish Naa Gegii: the Children’s Health and Well-Being Measure, and child study participant suggestions

Of the modified questions, nine were identified as problematic due to the vocabulary. For the most part, changes were made by replacing certain words with synonyms or adding an example. Five other changes were made to the content, given certain cultural particularities of the community. For questions 10 and 56, the children preferred the term ‘Elders’ compared to vieux. In addition, a child raised the idea of adding examples to question 17, including ‘Aboriginal Day’ and ‘Every Child Matters walk’. For question 57, the children proposed to specify the question by adding ‘malecite/Wolastoqiyik’ (Maliseet), which refers to the traditional language of the community. Two suggestions were also offered for question 59. First, the term médicaments traditionnels (‘traditional medicine’) was recommended to replace remèdes traditionnels (‘traditional remedies’) since it was more common in their vocabulary. Second, various examples were added based on suggestions that emerged during the interviews, such as sweetgrass, sage, and tobacco.

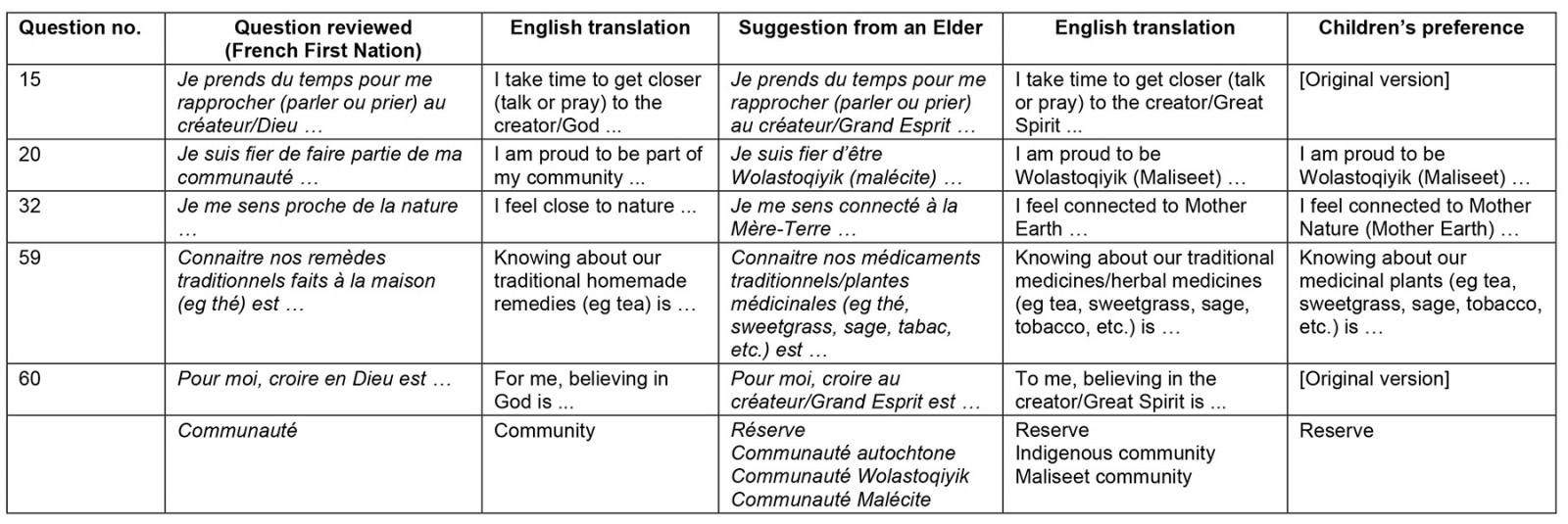

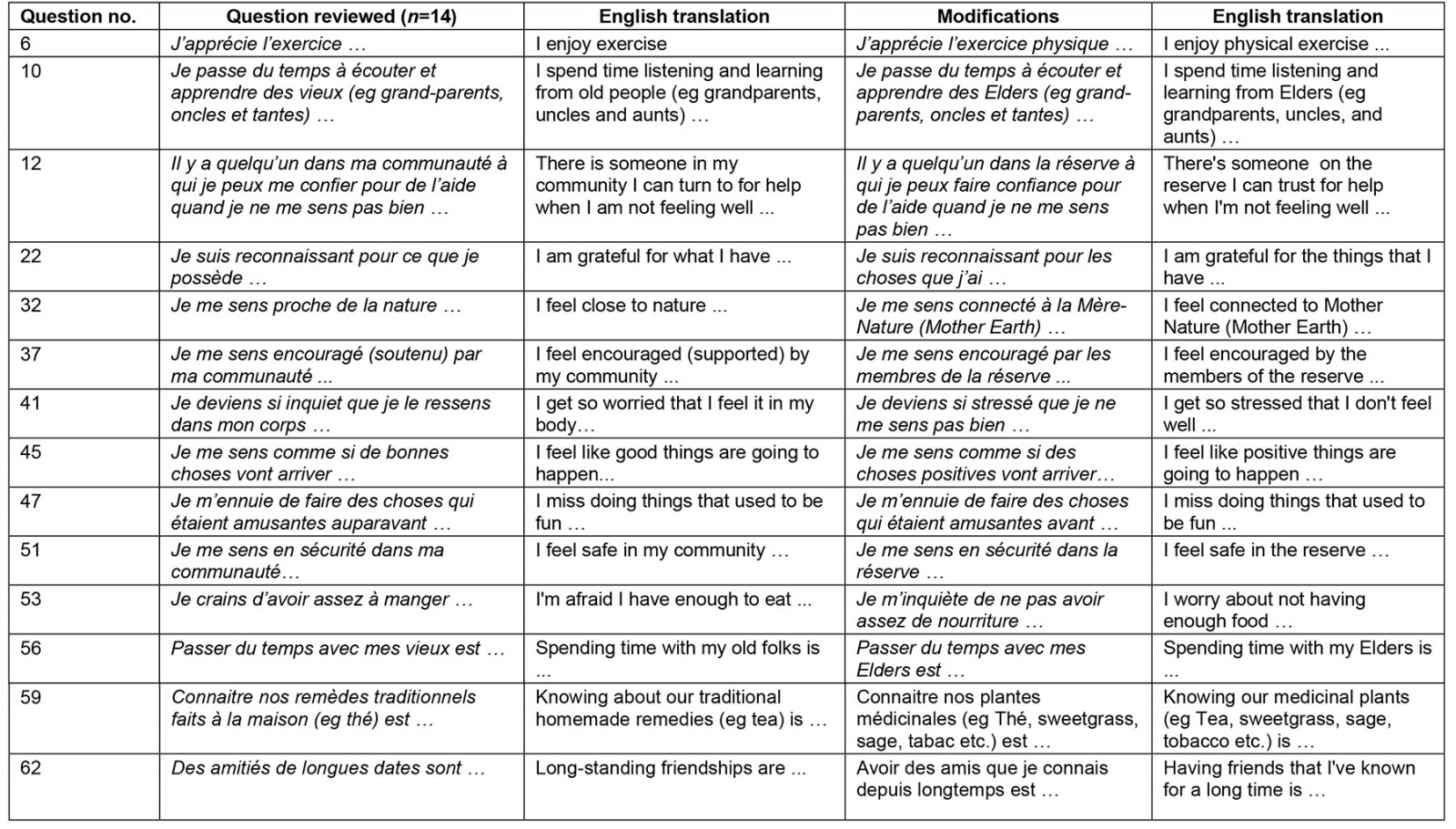

An in-depth discussion with the caregivers and the Elder prompted additional changes related to the cultural context. First, in the familiar lexicon of community members, it is rather rare for them to use the term communauté (‘community’) to refer to the Wolastoqiyik group specifically. It was suggested by the children to use the term ‘reserve’ and by an Elder and the caregivers to use communauté autochtone (‘Indigenous community’). The children’s preference was given priority, and this decision will be discussed thoroughly in the following section. Question 20, Je suis fier de faire partie de ma communauté … (‘I am proud to be part of my community’), was also discussed. As community members identify as Wolastoqiyik (Maliseet), it was suggested that we change this question to ‘I am proud to be Wolastoqiyik (Maliseet)’. This recommendation was also appreciated by the children. Finally, an important suggestion regarding the cultural aspect was raised in question 32 to modify the statement to Je me sens connecté à la Mère-Nature (Mother Earth) … (‘I feel connected to Mother Earth’). By revisiting the question, we realized that, in common vocabulary, ‘Mother Earth’ was well understood, but the literal French translation, Mère Terre, was not well understood. In this case, the use of Mère Nature (‘Mother Nature’) would possibly be a favourable alternative. We have therefore explored the possibility of presenting the French terminology Mère Nature accompanied by the English wording ‘Mother Earth’.

To verify the cultural accuracy of the questions subject to certain modifications, the new version of the questionnaire was reviewed with a community Elder. Following this meeting, the Elder recommended revisiting five additional potential changes, which then prompted a cross-check with a child participant. This stage of the analysis of suggestions is presented in Table 2. Discussions with participants made it possible to modify a total of 14 questions. These final modifications are presented in Table 3. This version of the statements will be integrated into the ACHWM questionnaire to produce an adapted version of the questionnaire for Wolastoqiyik children.

Table 2: Elder review and child study participant preferences for Elder’s suggested revisions to the French First Nation Aaniish Naa Gegii: the Children’s Health and Well-Being Measure

Table 3: Final modifications to 14 questions in the French First Nation Aaniish Naa Gegii: the Children’s Health and Well-Being Measure

Discussion

Our study aimed to culturally adapt the ACHWM for children living in the Madawaska Maliseet First Nation community located on the traditional unceded territory of the Wolastoqiyik.

Children from this community differ from other First Nations children involved in previous ACHWM studies27 due to unique factors such as limited exposure to their culture, their bilingual (French and English) environment, and their attendance at French and English public schools. Through a process of cognitive debriefing, we identified necessary revisions to ensure that the questions of the French First Nation ACHWM were well understood in their context.

Each of the nine children identified at least one opportunity for improvement during the interview process. Subsequently, two series of qualitative analyses were conducted, resulting in a total of 23 questions being reviewed and 14 questions (22.6% of the total) being modified.

The study results have raised interesting considerations that we deemed relevant for interpretation, even though they were beyond the scope of this study. Unlike other remote or isolated First Nations communities, the landlocked location of the Madawaska Maliseet First Nation in the city of Edmundston has certainly been an asset. However, this close relationship with the city has also impacted cultural continuity, particularly with the integration of the children into public schools. Prior to colonization, they and other First Nations communities had their own educational systems that were rooted in the community and in nature, where education was transmitted through oral traditions33. Although assimilation is no longer imposed as it once was with residential schools, the modern education system continues to uphold colonial values, marginalizing First Nations children34. Racism and discrimination further contribute to a sense of exclusion or a diminished sense of identity and self-value, which perpetuates their health and wellbeing35. Our study shows that, despite these challenges, Wolastoqiyik children display resilience and a strong desire to reconnect with their culture and learn from local teachings, primarily passed on through interactions with Elders and teachings at home. The revitalization of the culture and language is viewed as a source of healing for Indigenous populations36. Thus, the importance of cultural knowledge remains crucial even in societal contexts where Indigenous culture is not validated37.

Indigenous culture is deeply intertwined with the wisdom of Knowledge Keepers (Elders), traditional medicine, and a profound respect for Mother Earth14,16,17. Although specific terminology differs among communities, what stands out about the suggestions put forth by the children in this community is the link between their particular use of language and their cultural knowledge. This French version incorporated specific English terms and added examples and synonyms to align with their context. For instance, in reference to Knowledge Keepers, both French- and English-speaking children preferred the term ‘Elder’, leading us to replace the term vieux (‘old people’) used in the French First Nation version with ‘Elder’. Similarly, concerning the concept of Mother Earth, children showed a preference for the English term ‘Mother Earth’, but also expressed a liking for Mère-Nature (‘Mother Nature’) compared to the literal French translation Mère-Terre, which seemed to be less commonly used. Regarding traditional medicine38, our initial suggestions included médicaments traditionnels (‘traditional medication’) and plantes médicinales (‘medicinal plants’). However, upon discussions with the children, we discovered that the term médicaments (‘medication’) in their daily lives primarily referred to modern medicine. They preferred plantes médicinales (‘medicinal plants’) and suggested adding examples like sage, sweet grass, and tobacco. As the children mostly engaged in these practices during celebrations under the guidance of Elders rather than for healing practices at home, we modified the original question to Connaitre nos plantes médicinales (eg thé, sweetgrass, sage, tabac, etc.) est … (‘Knowing about our medicinal plants (eg tea, sweetgrass, sage, tobacco, etc.) is …’). Incorporating examples suggested by children from their cultural backgrounds, such as ‘Wolastoqiyik/I am proud to be Wolastoqiyik’, ‘Aboriginal Day’, and ‘Every Child Matters walk’, would be beneficial. However, adapting each version to cater to every local community might not be practical. To overcome this challenge, a potential solution could involve developing a guide for the communities. This guide would clarify the intent behind the suggested questions and examples, enabling children to complete the questionnaire without the necessity of customizing a version for each specific community.

Our results can also potentially show that the influence of colonization created generational differences within the community itself in terms of language and cultural affiliation. For instance, during the analysis of the parents' suggestions, the use of réserve (‘reserve’) or communauté (‘community’) was questioned. Although réserve (‘reserve’) is commonly used by community members, it evokes negative emotions associated with past injustices experienced by the Elders related to colonization. While it is crucial to acknowledge this aspect, the questionnaire aims to represent the voices of children. In a health and wellbeing measure like this, it is important to use a language that accurately reflects the children’s reality, to obtain reliable data for effective interventions. During our conversations with the children, we discovered that, when they spoke about their community, they were referring to a broader group gathering all the individuals they interact with, both in the Indigenous community and in the city. Hence, to let children define who is in their community, we chose to follow their suggestion and use réserve (‘reserve’).

Conclusion

As this study was limited to a specific population, it was important to have a diverse sample of participants that represented all the particularities of the community. One limitation of our study is the sample size, consisting of nine children, whose perceptions do not necessarily represent those of all children in the community. In addition, being in a bilingual community, our sample does not allow us to generalize to all children in the community since we could only adapt a French version. Taking into consideration the relatively small size of the community, we believe that our sample is representative and demonstrates good diversity in terms of age and gender. However, a larger sample size might have yielded more substantial results. Given the qualitative nature of our study, the primary aim of this study was to gain a comprehensive understanding of the community’s children’s perspectives. Recognizing the limitation of sample size, we conducted a thorough exploration of the content within our small sample to achieve data saturation. Future studies should address the sample size limitation by replicating this adaptation process in other Wolastoqiyik communities. This would contribute to a more comprehensive understanding and applicability of the results. Although it is important to anticipate variations related to cultural vocabulary, as each community maintains a unique cultural identity even within the same cultural group, this could not only improve the validity and relevance of this study’s findings but also provide valuable insights into the complex interplay of culture, language, and practices in diverse communities.

Clinical implications

This study emphasizes the global need for culturally relevant tools to accurately capture the unique cultural identities of Indigenous children in various regions around the world. Thus, in clinical settings, it is essential to be sensitive to local cultural contexts and not assume that each community shares the same beliefs and cultural practices. By adopting a similar adaptation process, professionals can enhance the effectiveness of wellbeing measures in capturing the unique cultural identities of children within their cultural contexts. This allows for better support in their development, as the traumas experienced by their ancestors have a significant impact on their wellbeing, values, and worldviews. This, in turn, contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of the specific needs prevalent for effective intervention.

Despite limited exposure to their culture due to the dominance of Euro-Canadian cultural influences, Wolastoqiyik children and their community maintain a distinct cultural identity, emphasizing cultural differences within First Nations communities. Acknowledging and validating their culture is vital for their wellbeing and plays a crucial role in assessing their health. This also allows for a more nuanced understanding and use of the ACHWM to meet the specific needs of the children in this community. By incorporating the modifications suggested during the adaptation process, we intend to enhance the effectiveness of this measure in capturing the unique cultural identities of children within their cultural contexts. This, in turn, contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of the specific needs prevalent for effective intervention. While health and wellbeing assessment measures like the ACHWM are crucial for screening the overall health of Indigenous children, relying on a sole Indigenous questionnaire is insufficient. Thus, this study underscores the importance of having accessible, flexible, and culturally adapted assessment tools to effectively evaluate the health and wellbeing of First Nations children. Utilizing tools like the ACHWM provides valuable insights into their health perceptions and cultural affiliations, considering both past and present social, cultural, and spiritual aspects. This knowledge enables experts to better address each child's specific needs and develop culturally relevant treatments.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the Elder, children, health professionals, and members of the community for sharing their knowledge and for their implication in this project.

Funding

This project was funded by a grant from the Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR); Listening to Indigenous Children’s Voices Promoting Indigenous Mental Wellness [I aM Well] led by Dr Nancy L. Young at the CHEO Research Institute.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are co-owned by the Madawaska Maliseet First Nation community, and restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under agreement for the current study and are therefore not publicly available. Data may be available from the authors upon reasonable request and with the permission of the Madawaska Maliseet First Nation community.

References

You might also be interested in:

2020 - Differences in US COVID-19 case rates and case fatality rates across the urban–rural continuum

2018 - Self-efficacy level among patients with type 2 diabetes living in rural areas