Introduction

Men, and rural men in particular, experience a disproportionate level of burden from alcohol and other drug (AOD) use1-5. Rurality, however, does not necessarily lead to rural–urban health disparities per se but may exacerbate the effects of, for instance, socioeconomic disadvantage, poorer service availability, and more hazardous environmental, occupational and transportation conditions6. The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic further increased health risks for people in rural areas. For instance, research has shown that COVID-19 has significantly impacted on rural wellbeing7, with increased mental health issues being reported for people with AOD dependency living in rural areas8.

An essential component of addressing risky health behaviour is access to, and utilisation of, health services9. However, men utilise health services at much lower rates than women10. This issue is amplified in rural areas where access to health and social services including AOD treatment is limited11. Although COVID-19 has negatively impacted the health of people in rural and urban areas, a positive development is the increased uptake of virtual care. This enabled continuity of services during COVID-19 by expanding the reach for AOD and other services12. The increased access to health and social services has particularly improved access for people in rural areas13,14. Virtual care does have some limitations such as poor access or quality of internet services and not being suitable for all client groups (eg high risk) and AOD treatment types12.

Despite these caveats, online interventions show promise in reducing AOD use behaviours in the short term15 but comparatively less is known about participants’ attitudes and experiences of virtual delivery of group-based treatment16. This is surprising given that group-based interventions are ubiquitous across the AOD sector. For example, mutual-help groups including 12-step and Self-Management and Recovery Training (SMART Recovery) are readily available in a virtual format and free to access. Importantly, peer-to-peer models have been suggested as an option for addressing gaps in service provision experienced by people in rural communities4.

Evidence shows that peer support groups are particularly useful as part of effective treatment support (after care) and may be beneficial in reducing use, risk of relapse and other risky behaviour17-19. The 12-step approach (eg Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous) is the longest running and most widespread mutual-help group for addictive behaviours. A range of secular alternatives are also available, including SMART Recovery, Women for Sobriety and LifeRing20. SMART Recovery mutual-help groups are based on a four-point program (building and maintaining motivation, coping with cravings and urges, problem-solving and lifestyle balance) and incorporate principles and strategies from cognitive behavioural therapy and motivational interviewing. All groups are led by a trained facilitator and are open to people experiencing a range of addictive behaviours and with a range or goals (eg moderation, as well as cessation). Participants are welcome to choose the number and frequency of meeting attendance according to their own needs and preferences. To date, much of the evidence of participant experience in online groups comes from 12-step approaches21-26, with comparatively less known about participant characteristics and experiences in online SMART Recovery groups27-29. Moreover, despite the potential of virtual health care for addressing geographical health disparities, less is known about the experience of men living in rural regions.

It is unclear whether the experience of online treatment will vary between rural and urban men, but there are reasons to explore this possibility. First, people in rural communities have concerns about privacy, confidentiality and gossip should their attendance at AOD services become known30. Gossip involving moral condemnation and the associated shame and stigma have been suggested to negatively affect treatment affiliation and early bonds in recovery services30. Second, it has been found that those in rural communities can be particularly stoic31,32. This may reduce their willingness to share their emotions or vulnerabilities. In other health domains, the relationship between geographic remoteness and intention to use a telephone-based support services was partially mediated by stoicism and subjective norms33. As rural and metro areas differ in their proportion of First Nations Peoples34, we might also expect the experience of rural and urban participants to differ due to cultural differences in the experience of telehealth34-37.

In this article we will examine the experiences of men living in rural compared to urban areas with online SMART Recovery groups. Specifically, we will examine similarities and differences between rural and urban attendees in terms of ratings of engagement, experience with these groups (including technical difficulties) and perceived utility.

Methods

This manuscript reports on a subanalysis of a study designed to evaluate the scaling up of Australian SMART Recovery mutual-help groups in response to the COVID-19 pandemic38.

Participants

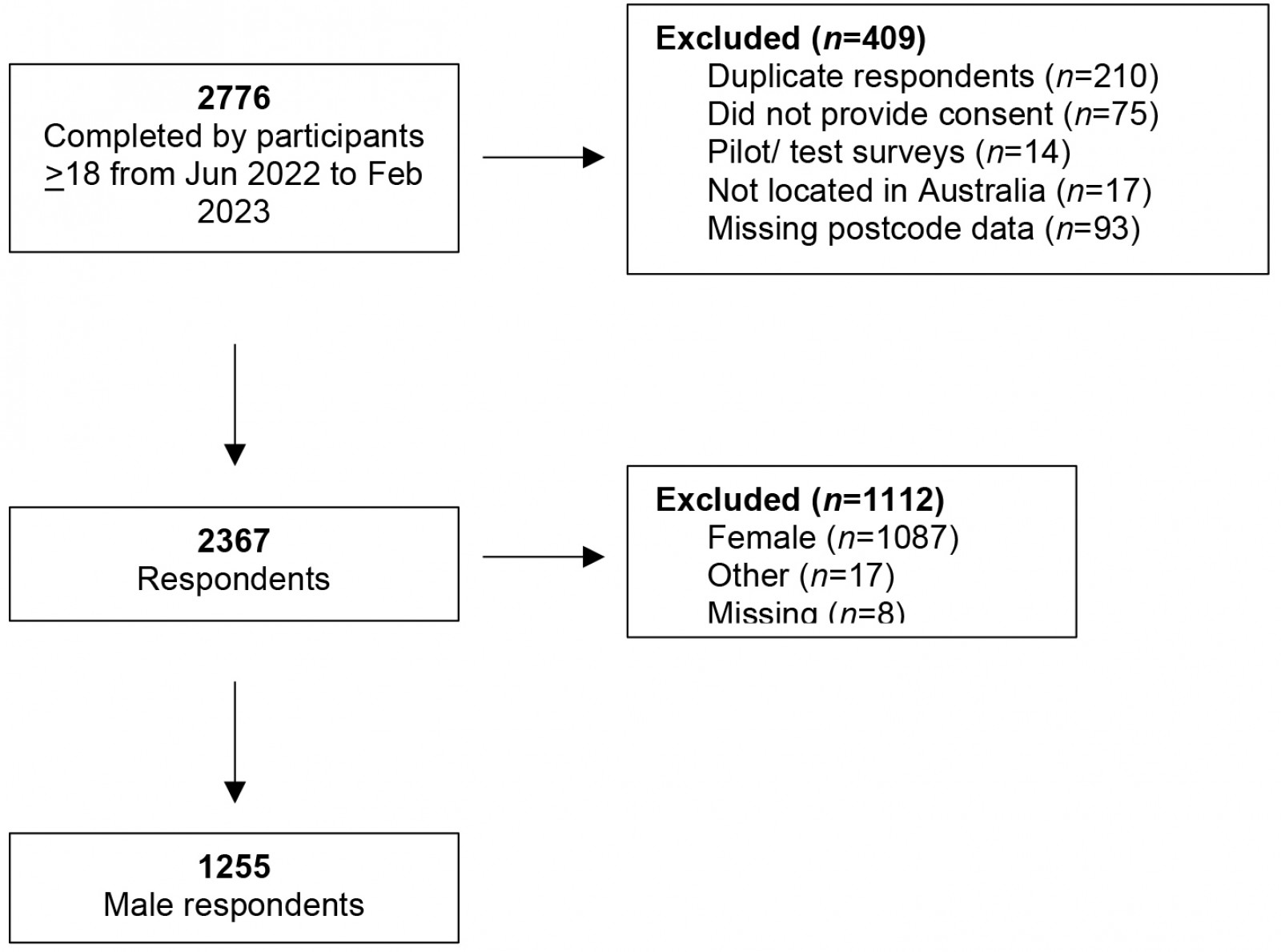

Participants comprised a self-selected, convenience sample of adults (aged ≥18 years) attending online SMART Recovery mutual-help groups during the period of data collection (June 2020 – February 2023). A total of 2776 people completed the survey. A combination of IP address, gender and age were used to identify and filter out duplicate respondents (n=210). After accounting for consent, pilot/test surveys, participant location, missing data and gender (Fig1) the current sample comprised 1255 male respondents. Analyses were restricted to men because AKB is supported to conduct this work by a targeted funding call identifying the wellbeing of rural men as a key priority area.

Figure 1: Consort flowchart.

Figure 1: Consort flowchart.

Procedure

Participants completed a brief online questionnaire developed inhouse by SMART Recovery Australia to routinely capture participant characteristics and experiences. The questionnaire was administered via a SurveyMonkey link embedded into the post-group Zoom exit page. Participants were asked to complete the questionnaire only once, based on their most recent online group.

Assessment

Items captured basic demographic information and reason(s) for attending the online group that day. Eight five-point Likert scale items captured participant engagement (the degree to which participants felt they were welcomed, supported and had an opportunity to contribute), experience (skill of the facilitator, experience of technical difficulties) and perceived utility (acquisition of practical information and strategies, degree to which the group was experienced as helpful and intention to continue attending). Participant use of the ‘seven-day plan’ (a core behaviour-change technique utilised in Australian groups) was also assessed. Completion of the questionnaire was anonymous, voluntary and no incentive was provided.

Data analysis

Demographic data were summarised using descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, range, sum and/or proportion), as appropriate. Participant postcode was used to categorise participants according to the five levels of ‘remoteness’ defined by the Australian Standard Geographical Classification. Consistent with published recommendations for examining ‘rural and remote’ Australians39, response categories were collapsed for analysis (Major City v Inner Regional/Outer Regional/Remote/Very Remote). Response categories for the Likert scale items were also collapsed (strongly disagree/disagree/slightly agree v agree/strongly agree) for analysis. Sensitivity analyses conducted using strongly disagree/disagree v slightly agree/agree/strongly agree yielded a similar pattern of results (Appendix I). Survey responses from men attending in major city locations (henceforth referred to as urban areas) were compared to people attending rural locations using two-sided χ2 (or Fisher’s exact test where appropriate). All analyses were conducted in the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences v27 (http://www.ibm.com/support/pages/downloading-ibm-spss-statistics-27). Bonferroni correction was applied to adjust for multiple comparisons (p=0.005).

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was granted by the Joint University of Wollongong and Illawarra Shoalhaven Local Health District Health and Medical Human Research Ethics Committee (2020/ETH02893).

Results

Participant characteristics

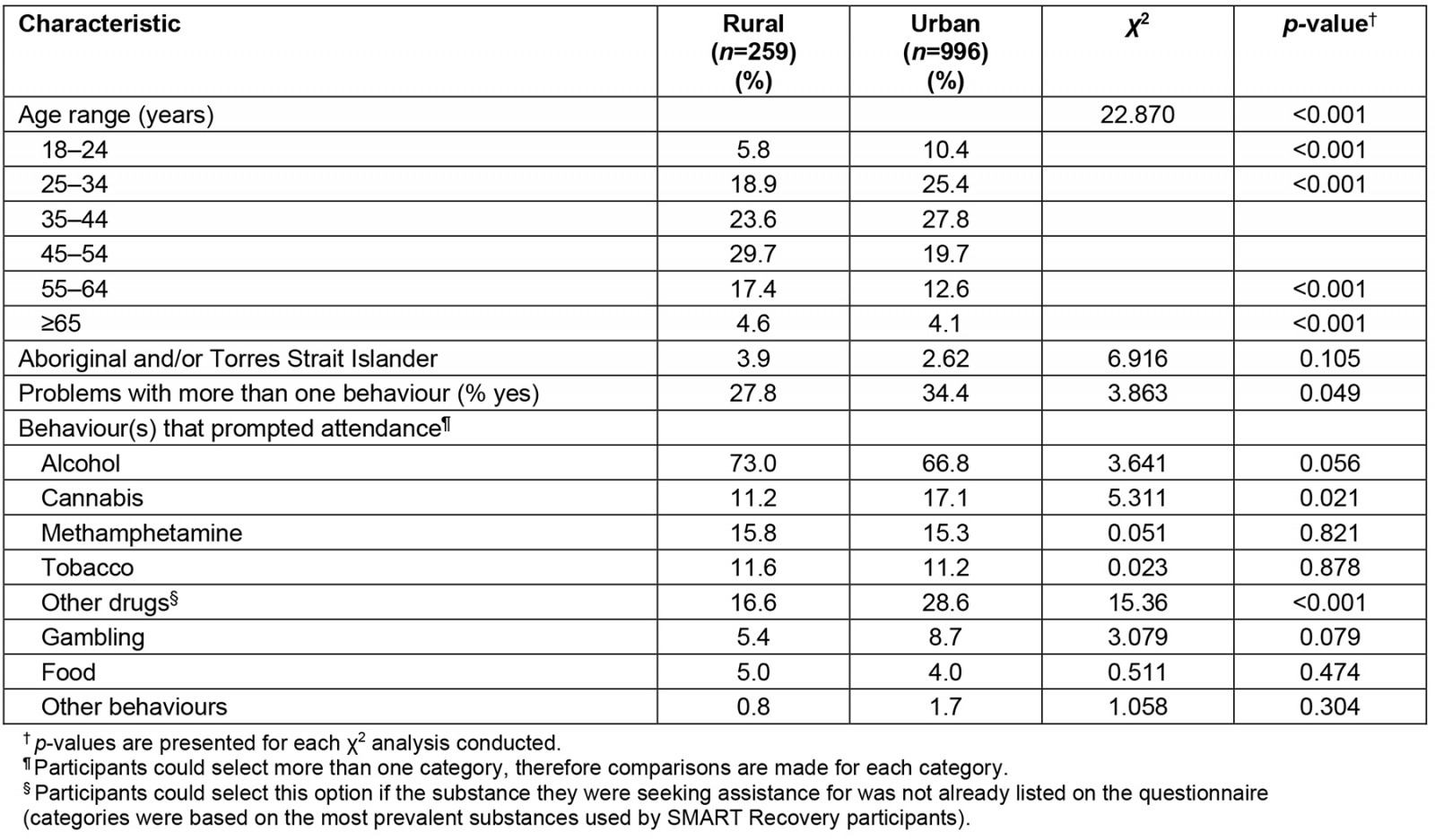

Alcohol use was the most frequently reported reason for attending SMART Recovery groups for both rural and urban attendees (73.0% v 66.8%). More than a quarter of both rural (27.8%) and urban attendees (34.4%) selected more than one reason (alcohol, cannabis, methamphetamine, tobacco, other drugs, sex, pornography, gambling, internet, shopping, food, other behaviours) for attending SMART Recovery groups. Rural attendees were older than their urban counterparts (p<0.001) and were less likely to endorse ‘other’ drug use as a reason for attending (28.6% v 16.6%, p<0.001). More details regarding the participant characteristics can be found in Table 1.

Table 1: Study participant characteristics

Engagement and experience with SMART Recovery groups

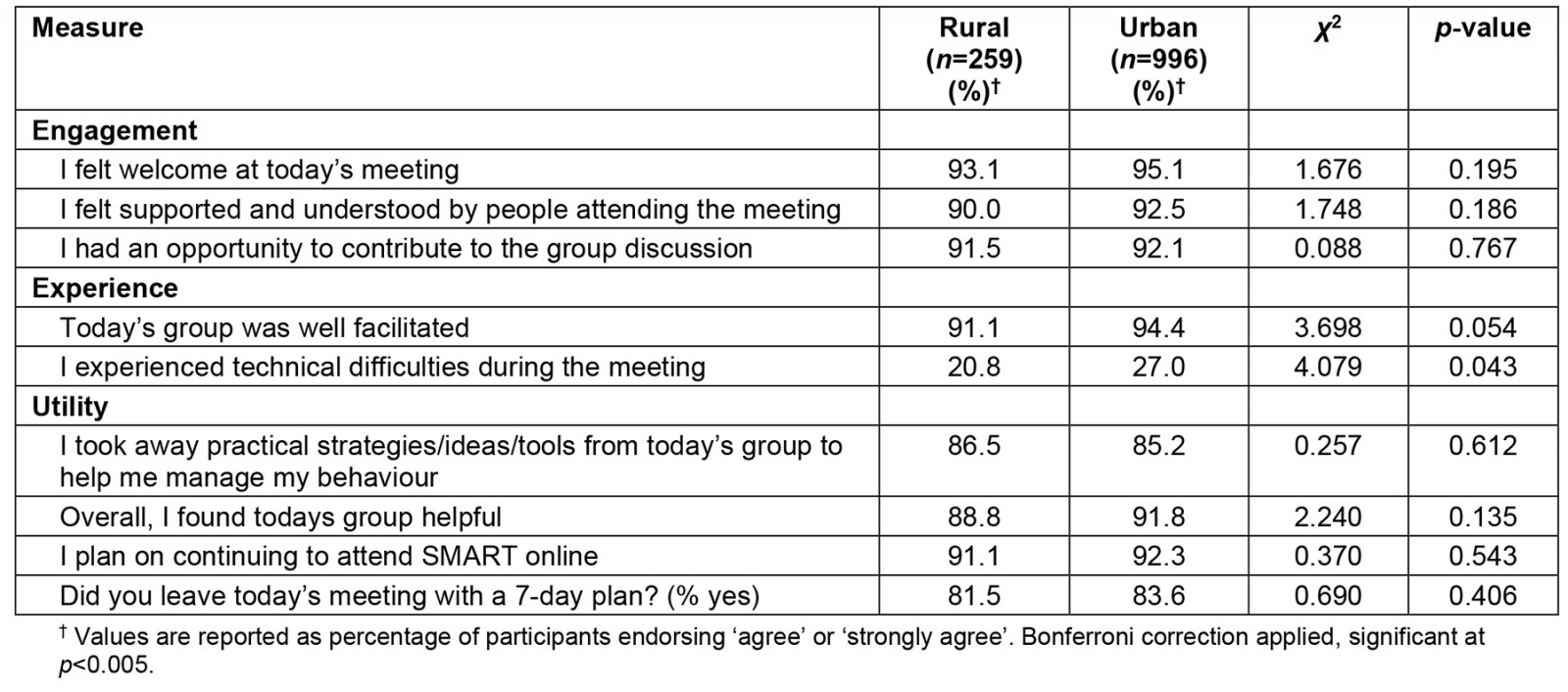

Participants reported a high level of satisfaction with online SMART Recovery groups. No significant differences were found between the two groups. Rural and urban men reported that they felt welcome and supported, had the opportunity to contribute to discussions, and felt the group was well facilitated. They also took away practical strategies and planned to continue to attend the groups in the future. Around a quarter of rural (20.8%) and urban (27.0%) attendees experienced technical difficulties during the meeting. See Table 2 for more detail.

Table 2: Comparison of self-reported experience of online SMART Recovery groups for men located in rural areas and major cities

Discussion and conclusion

This study contributes new knowledge regarding similarities and differences in the experience of online SMART Recovery groups from the perspective of men living in rural and urban areas. Despite around a quarter of both rural and urban attendees reporting to have experienced technical difficulties, self-reported engagement, experience and perceived utility were highly rated by both groups. Our findings lend further support to the potential of online mutual-help groups for reaching otherwise difficult and underserved populations24,27,40,41. This is particularly important for men living in rural locations whereby utilisation of face-to-face services is complicated by a range of accessibility and other sociocultural barriers42-46. Further controlled trials, ideally with in-depth qualitative exploration and longitudinal follow-up, are warranted to clarify the role of online mutual-help groups for addressing disparities in service utilisation and health outcomes among men living in rural locations.

Online SMART Recovery participants from rural regions were older than their urban counterparts. They were also less likely to select ‘other drug use’ as a reason for attending SMART Recovery. These findings are consistent with published comparisons of the demographics and substance use patterns of urban and rural populations in Australia5,47. The largely positive experience reported by attendees is especially encouraging in light of evidence that engaging older people from rural regions requires that online services adequately account for the specific needs and preferences of this cohort48. Also of note is that technical issues, such as a bad wi-fi connection, are more often reported as an issue for those living in rural areas48, but there were no significant differences in terms of technical experiences between both groups. Indeed, 2019 data from the OECD positions Australia as the fourth poorest performing country with regard to broadband speed and quality. Nevertheless, given that technical difficulties were reported by around a quarter of each group, efforts to understand and address the specific technical barriers experienced by attendees are warranted.

Our data also illustrate that there were no significant differences in terms of the proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people located in rural or urban areas. This is interesting as the distribution of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander people across rural and urban areas has shifted; whereas the majority used to reside in rural areas, most are now living in urban areas (65.6%)49. One could therefore perhaps expect that the number of urban Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander attendees would be higher compared to rural attendees. In van de Ven et al’s research on the impact of COVID-19 on AOD treatment services, service providers noted that it was hard to maintain cultural safety when engaging Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients via technology12. It was also noted that face-to-face service delivery and the phone were preferred over receiving services via online means by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients. Therefore, to increase their engagement in online mutual-help groups, and maximise the potential of this service for addressing health disparities, extensive community consultation is needed to develop and evaluate culturally sensitive telehealth solutions.

The current findings must be considered in light of several limitations. Our findings are derived from a cross-sectional convenience sample of participants and are therefore subject to bias. We did not collect data on the number of participants attending SMART Recovery groups across the study period. Therefore, although participant characteristics are comparable to published accounts29, generalisability is unclear. Post-group administration of the questionnaire also means that we did not capture the characteristics of those attendees who left early (and therefore may have been less satisfied with the group). Although promising, our findings focus more on satisfaction and fall short of targeted exploration of participant experience. Future research would benefit from exploring the validity of dedicated experience measures50,51 for assessing participant experience of online service provision. Likert scale items were dichotomised for analysis, and although this approach aids interpretation52 the number of response categories was positively skewed. Dichotomising geographical location also misses the variations in experience that have previously been demonstrated across the differing levels of remoteness53. In addition, our study does not assess the effectiveness of SMART Recovery groups and no judgement can be made regarding the extent to which attending these groups contributes to reaching treatment goals (eg a reduction in AOD use). Finally, gender was based on self-identification as a man. This means that we are unable to explore potential differences in the experience of cisgender and transgender men. Future research should examine the experience of online groups for other gender identities and incorporate published recommendations54 for sensitively and comprehensively assessing sex and gender.

Funding

The authors wish to acknowledge this study was funded by NSW Health through the Peregrine Centre’s Rural Mental Health Partnership Grant. This manuscript is a subanalysis of a project that was commissioned by SMART Recovery Australia and supported by funding from the Commonwealth Government of Australia under the Alcohol, Tobacco and Other Drugs – COVID-19 Response Grant. Neither SMART Recovery Australia nor the funding body had direct input into the design of the study, analysis and interpretation of data, or writing and submission of this manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no financial conflicts of interest. At the time of the study all authors volunteered as members of the SMART Recovery Australia Research Advisory Committee.

References

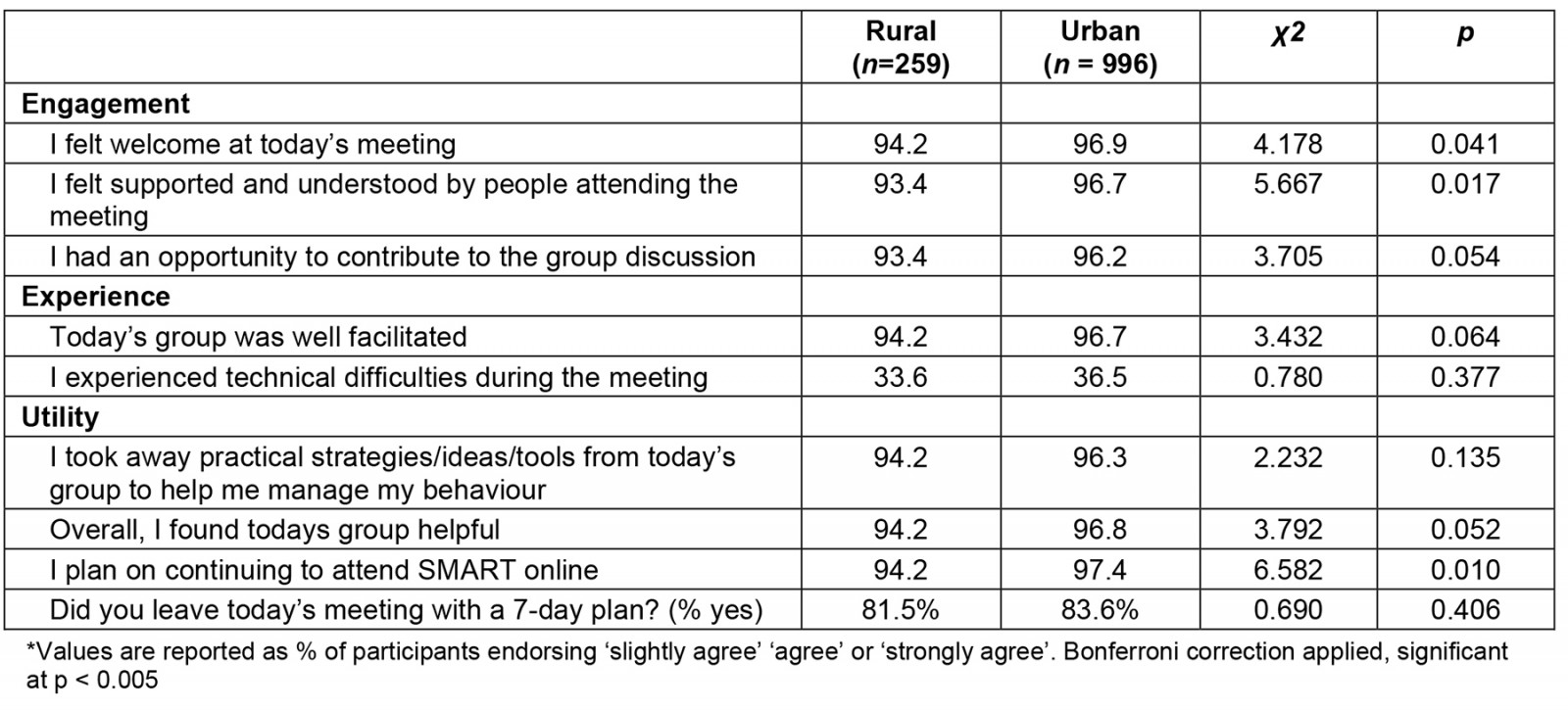

appendix I:

Appendix I: Comparison of self-reported experience of online SMART Recovery groups for men located in rural areas and major cities

You might also be interested in:

2020 - Evaluating a centralised cancer support centre in the remote region of Northern Norway

2020 - Fluvial family health: work process of teams in riverside communities of the Brazilian Amazon