Context

Rural regions are home to one-quarter of the population and contain the vast majority of the land, water and other natural resources in OECD countries1-3. Three-quarters of rural residents in OECD countries live in regions with close connections to cities but close to 1 in 10 of the total population (75 million people) live in remote rural regions: over one in five in Greece, Norway, Finland, Sweden, Estonia and Australia3. Rural areas play a key role in food production and environmental services and are an integral part of economies. However, they face a unique set of challenges. OECD analysis reveals that spatial inequalities in income have widened. Over half of 27 OECD countries saw income inequalities between their small (territorial level (TL) 3) regions increase between 2000 and 20204. (The OECD has established two levels of geographic units at the subnational level, mostly matching the national borders and administrative regions. TL2 comprises 362 larger regions, which contain TL3 regions (comprising 1794 smaller cities and rural regions). This classification system facilitates the comparison of geographic units at equivalent levels and is commonly used by countries to inform regional and rural policy development.)

Rural areas are also on the frontline of population aging and this is expected to increase over time5. The proportion of ‘shrinking’ regions (regions experiencing population decline) in 2001–2021 was 28 percentage points higher in remote regions compared to large metropolitan regions4. (Population decline and aging present significant challenges for numerous OECD regions. These challenges include increased per-capita costs for services and infrastructure provision. The OECD advocates for enhanced regional and rural policies to address the issues associated with population decline.)

Promoting rural development comes with numerous policy and governance challenges. The cascading effects of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the spatial challenges caused by the pandemic, as well as the expected decline in subnational government finances4, have important implications for national, regional and rural policy. The war has created significant inflationary pressures and supply chain disruptions. Energy plays a significant role in driving economic growth and improving quality of life5. Regions around the world have experienced soaring energy prices as a result of the war. The less diversified energy mix and higher incidence of low-income households in rural areas have made them more vunerable to energy poverty4. COVID-19 exposed structural weaknesses in rural health systems. Specifically, it brought into focus the gaps in health resources available to cope with a large and sudden influx of seriously ill patients.

Additionally, policymakers will increasingly need to take action to address both short- and long-term impacts of megatrends – digitalisation, the green transition, demographic change and globalisation – and their spatial impacts, which could further amplify existing regional inequalities (Box 1). Some regions will need to undergo major transitions to adapt to challenges, while others are better equipped to seize the opportunities created from the transition. Megatrends also provide opportunities to boost sustainability and resilience. While all regions have been adversely affected by these shocks, their capacities to adapt and capitalise on the opportunities vary significantly6.

Box 1: Global megatrends and rural areas2,6,7.

| A number of global shifts are likely to influence how rural areas can succeed in a more complex, dynamic and challenging environment. | |

| Population aging and migration: The general aging trend across OECD economies is expected to continue. The capacity for rural communities to provide an attractive offer and integrate newly arrived migrants will shape their ability to address the challenge of aging and shrinking populations. | |

| Urbanisation: The rural-to-urban migration trend has stabilised in OECD economies. However, population aging, particularly in rural remote areas, will tend to shift the political balance within countries toward metropolitan areas. | |

| Global shifts in production: The production of goods and services is increasingly dispersed across countries as multinational enterprises pursue offshore, reshore and outsource activities. Rural regions will need to continue to specialise and focus on core areas of advantage to compete in the global economy. | |

| Rise of emerging economies: The centre of economic gravity is likely to continue to shift away from the North Atlantic toward Asia, Africa and Latin America. By 2030, emerging economies are expected to contribute to two-thirds of global growth and be major centres of global trade. A larger global middle class will translate into increased demand for raw materials, food and technologies from rural places in OECD economies. | |

| Climate change and environmental pressures: The United Nations Paris Agreement provides a framework for global action to limit temperature increases to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. Future population and economic growth is likely to further increase pressures on the environment. | |

| Technological breakthroughs: A number of emerging technologies associated with digitalisation, including automation and artificial intelligence, decentralised energy generation, cloud computing and the Internet of Things, and nanotechnologies, will open up new production possibilities and transform access to goods and services. This is likely to result in labour-saving technologies and product innovations in agriculture, forestry and mining, and associated value-adding. | |

Issue

Addressing a person’s wellbeing and designing the appropriate policies to do so require taking geographical context into account. For this reason, the OECD has consistently called for the rethinking of policies to tackle the ‘persistent underutilisation of potential and reducing persistent social exclusion to move from place-blind to place-based policies’8. This recommendation is often coupled with evidence that policies can deliver rural places that are more prosperous, connected and inclusive, when they are ‘well-designed’, ‘leverage local assets’ and are ‘executed in co-ordination across levels of government and between the government, the private sector and civil society’9. Rural proofing is a tool aimed at helping policymakers develop more nuanced, rural-friendly policies, making them fit for purpose in rural areas. It entails the early sharing of evidence about rural dynamics during the policy development process, enabling policymakers to make adjustments before finalising the policy.

Rural proofing is a process, not a policy. It is a guidance mechanism involving several interconnected variables designed to support and enhance the quality of government decision-making concerning rural communities. This is evident in the definitions and approach to rural proofing. In England, the Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs describes it as ‘practical guidance for policymakers and analysts in government to assess and take into account the effects of policies on rural areas’10. In New Zealand, it is ‘taking into account the particular challenges faced by the rural sector when designing and implementing government policy’11. The European Commission defines it as ‘reviewing policies through a rural lens, to make these policies fit for purpose for those who live and work in rural areas’12.

The definitions of rural proofing may vary but the core aims are the same. It is designed to be a ‘process’ that enables decision-makers to ‘think rural’ when designing policy interventions in order to prevent negative outcomes or trigger positive outcomes in rural areas. While similar in form to impact assessments when designed and applied, it is broader in scope, reach and objectives. A key difference is that it mandates a commitment to ‘undertake systematic procedures’ to ensure that ‘all of its policies, programmes and initiatives, both nationally and regionally, take account of rural circumstances and needs’ before the policy is implemented13. In practice this means the review should occur early in the policymaking phase to allow for the consideration of ‘any likely impact of policy actions on rural areas in advance’14. For example, in Finland, rural proofing is used to ‘identify whether the proposals that are in ‘development’ and the ‘means selected to implement them have significant impacts in and on the rural areas’15.

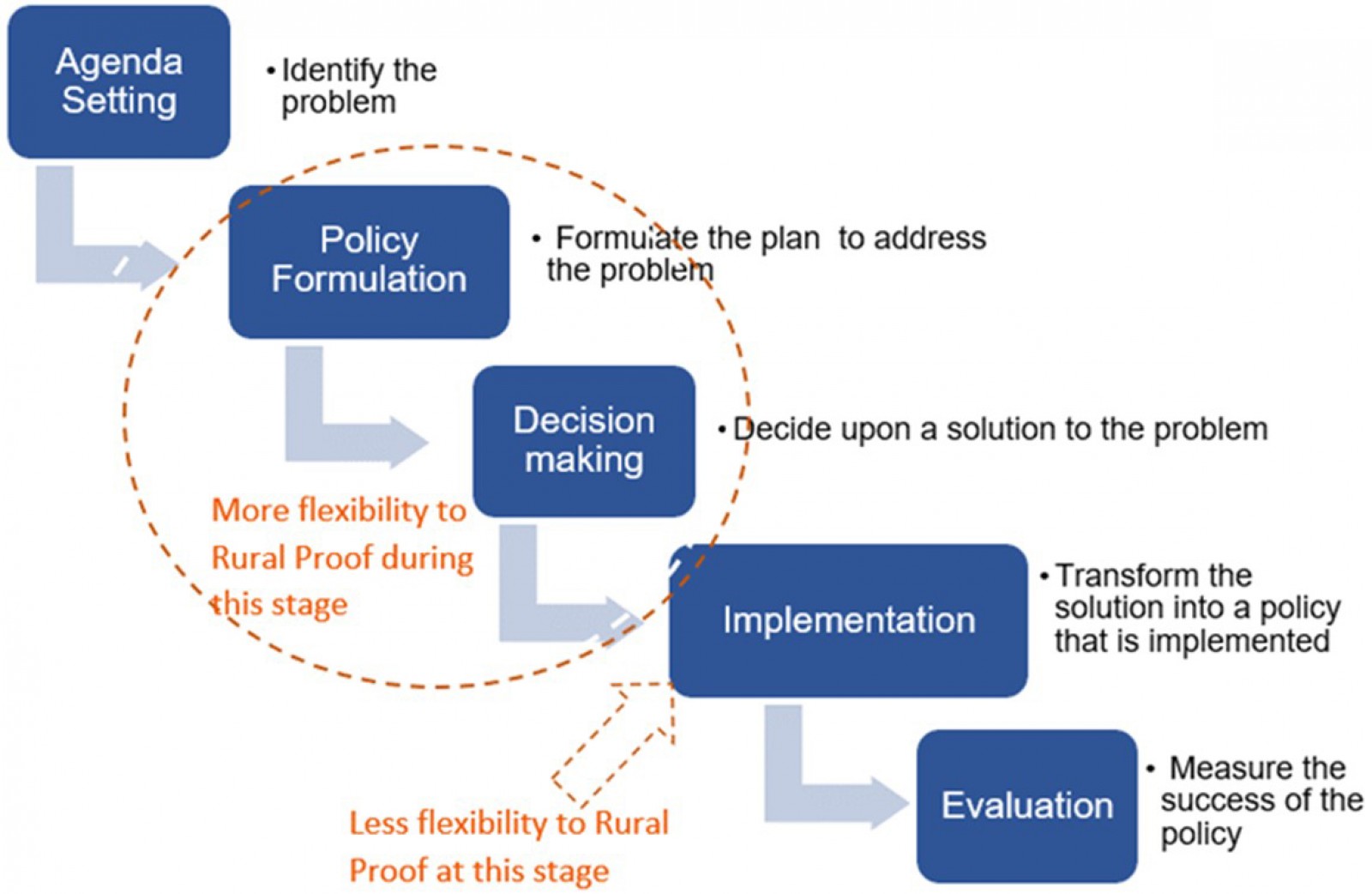

Some in the academic community remain hesitant to embrace rural proofing. In To Rural Proof or Not to Rural Proof: A Comparative Analysis and Rural Proofing Policies for Health: Barriers to Policy Transfer for Australia, the authors present compelling reasons as to why rural proofing would not work using Australia as a focal point of analysis. In the first article, Shortall and Alston posit that rural proofing ‘does not makes sense’ in Australia16 while Sutarsa et al argue that ‘rural proofing is not the best option’ or the way to ensure that health policies have a rural lens in Australia17. Correspondingly a common critique of rural proofing is the fact that the assessments are undertaken later as ‘ex poste impact assessments of policy, rather than ex ante assessments during the policy design phase’14,18. Policymaking is not a static process, and the policymaking cycle includes five main areas: agenda-setting, policy formulation, decision-making, implementation and evaluation (Fig1).

The five areas in Figure 1 provide a framework to better understand how policy is developed. During agenda-setting new issues that may require government action are identified. Policy formulation focuses on developing policy options to address issues and in the decision-making state government decides on a particular course of action. In the implementation stage the chosen solution is put into effect and during the evaluation state the policy is monitored to determine if it is achieving the intended goal. Policymakers use evidence at various stages of the policymaking process – from problem definition to identifying a solution19. This makes timing, finding the crucial moment to influence policymaking, a very important factor, while some feel that ‘thinking rural’ needs to be relevant at all stages, from drafting the initial policy strategy all the way to impact assessment after implementation20. Arguably, the opportune moment for rural proofing is during the period after the problem is identified but the solution is not yet finalised for implementation. This is when the rural proofing supporting instruments, such as data and guidance documents, can improve impact in rural areas by identifying new issues for the policy agenda and potentially changing how decision-makers perceive problems and solutions.

Figure 1: Rural proofing and the policymaking cycle. Source: Adapted from Benson D, Jordan A (2015)21.

Figure 1: Rural proofing and the policymaking cycle. Source: Adapted from Benson D, Jordan A (2015)21.

Other challenges that persist include13,18,22,23:

- over reliance on political-level buy-in to advance rural proofing

- limited or no knowledge and understanding of rural issues and areas by policymakers outside rural departments

- limited effectiveness of the department responsible for coordinating rural proofing

- confusion across government about the roles and responsibilities of the coordinating agency

- lacklustre support for the coordinating body to enable cross-government collaboration

- policy examinations undertaken (more often than not) as ex poste impact assessments of policy rather than ex ante assessments during the policy design phase

- execution of rural proofing at the ‘right’ time to influence policymaking

- adapting the rural proofing process to the different policymaking process at different levels of governance (eg the national, regional or local level).

This policy report looks at how to embed rural proofing into the policy space by setting up mechanisms that systematically assess policies for their impacts in rural areas to foster more balanced results. The report is based on a literature review of published research and discussions facilitated by the OECD, focusing on rural proofing. The first meeting took place on 28 March 2022, with experts who have written extensively on rural proofing. The second meeting, held on 25 April 2022, involved government officials from various countries (including the UK, Canada, Finland, Sweden and Ireland) who have experience in implementing rural proofing. Another meeting, on 9 June 2022, included government officials and stakeholders from countries new to or interested in expanding rural proofing, such as Australia, New Zealand, Estonia, Spain, the US, Chile and Italy. These efforts were complemented by engagement with the European Network for Rural Development Thematic Working Group on Rural Proofing. The European Commission’s Long-Term Vision for Rural Areas underscores the significance of rural proofing. The European Network for Rural Development Working Group, launched to support the long-term vision, served as a platform to exchange experiences and develop recommendations for the implementation of rural proofing mechanisms within the European Union at national, regional and local levels. Lastly, the 13th OECD Rural Development Conference in Cavan, Ireland, placed a special emphasis on rural proofing by featuring a panel of government officials from several countries each providing exampled of health-focused rural proofing efforts. The panel was executed in collaboration with WHO.

Ethics statement

Established in 1999, the OECD Regional Development Policy Committee designs and implements effective place-based policies to improve living standards and wellbeing for citizens across all regions, cities and rural areas. It provides internationally comparable subnational data to inform global debates on policy, finance and governance.

The committee meets twice yearly with relevant ministries and organisations to develop a vision of place-based, multi-level and multi-sectoral regional development policy. Since its creation, the committee has informed many global debates and is a leading forum for high-level policymakers.

The Regional Development Policy Committee has subsidiary bodies that advance the work of the committee by reviewing and discussing all work relevant to each committee and approving it for publication.

The Working Party on Rural Policy is the subsidiary body that reviews and approves all work on rural development policy. The committee also meets twice a year.

As required by OECD procedures, the present article was presented to the Working Party on Rural Policy for discussion and approval at the 28th session of the Working Party on Rural Policy, 28 November 2022 at OECD headquarters in Paris, France.

Lessons learned

Rural proofing is able to support different aims for rural communities

Over the years, the OECD has collected a significant body of evidence on the extent and drivers of inequalities, social mobility and equal opportunity. The most recent contribution to this body of work, analysing these elements through a regional lens, is the OECD regional outlook 2023: The longstanding geography of inequalities4. The report makes several important observations, including that gaps in regional performance undermine growth, productivity and wellbeing, and come with economic, social and political costs. It highlights how reducing inequalities can be highly beneficial for regions and society as a whole and may well have scope for a new or improved relationship between government and citizens4. In OECD member countries, there is a growing awareness of the need for additional measures to ensure that the potential effects on rural communities are taken into account before finalising policies.

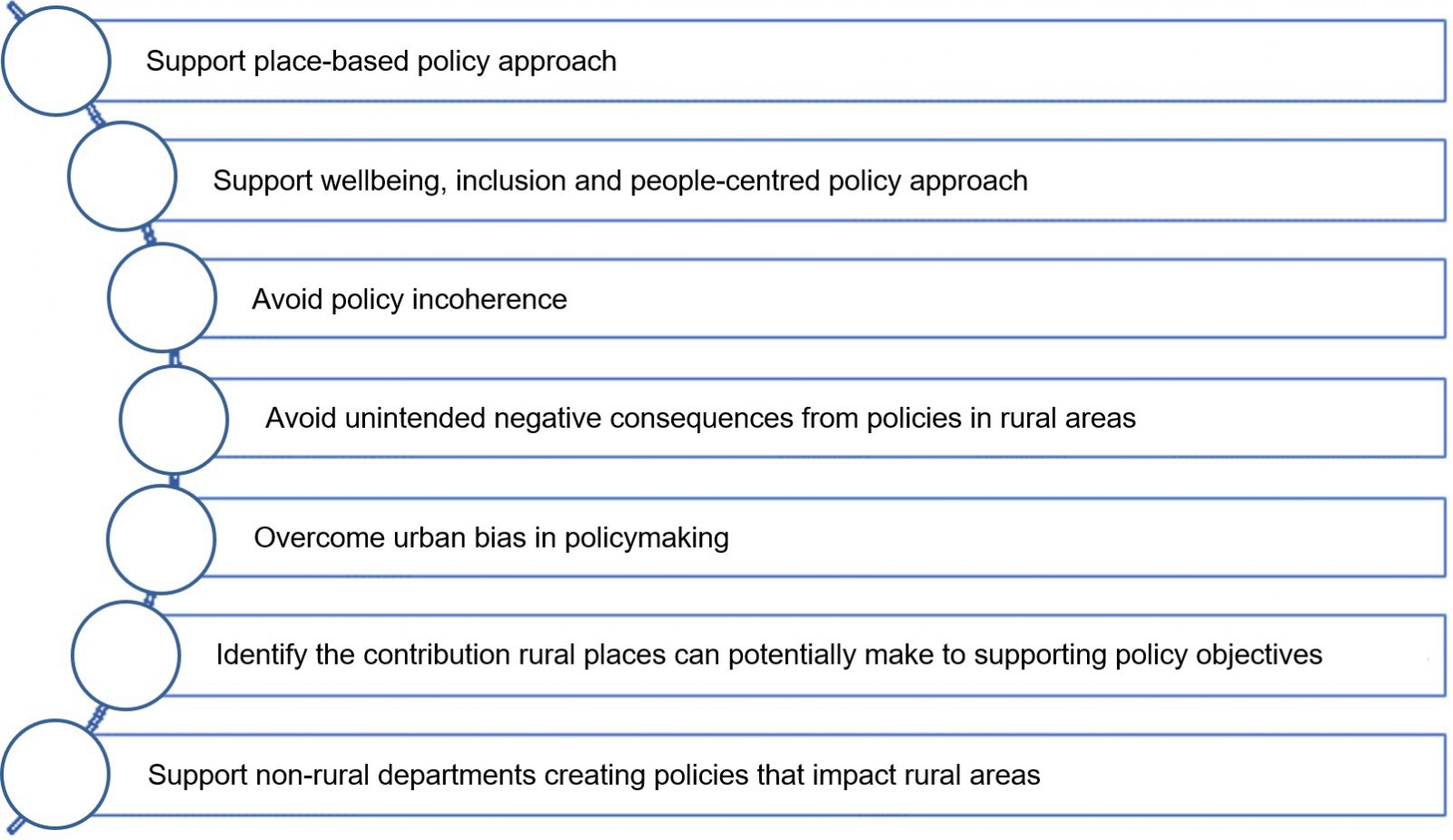

Rural proofing is well positioned to support the place-based approach to policy development and the consideration of the wellbeing of rural constituents in policy formulation. More broadly, it can help improve policy coherence for rural regions and avoid unintended consequence from policies in rural regions and the urban bias in policymaking. For example, the 2018 gilet jaunes protests in France were triggered by the government’s decision to keep increasing a direct tax on diesel and a carbon tax. This move infuriated rural constituencies, which perceived it as disproportionately affecting those who relied more on cars to commute every day. Rural proofing can also support non-rural departments creating policies that impact rural areas. Examples are in improving digital infrastructure and introducing housing policy reforms targeted in rural areas that can raise wellbeing standards. Rural proofing has the potential to add value in multiple areas, as illustrated in Figure 2. Several key points are emphasised below.

Figure 2: Rural proofing supports different aims for rural communities.

Figure 2: Rural proofing supports different aims for rural communities.

Rural proofing supports the place-based approach to policy development

In Distributed rural proofing – an essential tool for the future of rural development? Kenneth Nordberg argues that the linkage between the place-based approach and policymaking should be strengthened by incorporating rural proofing mechanisms. This will facilitate seamless responses to change across various levels of governance13. Place-based policymaking is an important and long-standing pillar of OECD recommendations. Indeed, the OECD’s Regional Development Policy Committee has spent the past 20 years engaging in quantitative and qualitative analysis of the place-based policy approach to rural and regional development and building standards and good practices. This work emphasies that place-based policies are essential to building inclusive, resilient communities. The OECD Regional Outlook 2014 called for the ‘adopt(ion) of a place-based approach to rural policy because the need for a more tailored approach was arguably greater in rural territories’24.

Rural proofing supports the wellbeing approach to policymaking by putting people first

Today, it is widely acknowledged that people’s wellbeing should be the target of development policy. Deep structural inequalities between places have consequences that reach far beyond the economy and impact overall wellbeing. The OECD report How’s life? 2020: Measuring well-being, highlights the limitations of GDP as a reliable metric for policymakers. It suggests that governments should adopt a broader perspective to gauge the wellbeing of individuals and communities25.The OECD regional outlook 2019 highlighted that the sustained health of communities relies not only on economic expansion and competitiveness, but also on the wellbeing, inclusion and environmental sustainability of residents26. The report notes that place-based initiatives don't just benefit national economies; they also contribute to a more inclusive and sustainable growth model, with a strong social dimension that helps build a fairer society27.

The broad-reaching costs of failing to tackle regional underperformance include reduced employment and earnings, social mobility and life satisfaction, and higher prevalence of welfare dependency and health issues4. Citizens are demanding better living standards and the reduction of inequalities, which is putting more pressure on governments to steer recovery towards resilience and inclusivity. Public discontent with less opportunities and the perception of being overlooked is visible in the use of the ‘ballot box and, in some cases, outright revolt’ to garner greater attention to their plight28.

More and more, governments are paying greater attention to dimensions of wellbeing, such as health, housing, education, access to water and civic engagement. Considering wellbeing recognises that economic progress encompasses a broader view of social progress beyond production and market value. The OECD Well-being Framework25 considers whether life is getting better for people and includes a distinction between wellbeing today and the resources needed to sustain it in the future25. Rural regions have different geographies – from communities near urban areas to remote, sparsely populated places so strategies for a rural region close to a city may differ from a strategy for a remote region. For this reason, the OECD’s Rural Well-being Framework3 promotes a people-centred approach that factors in the rural context. It is built on:

- three types of rural: those near a large city, those within a small or medium city and those in remote regions

- three objectives: not only economic objectives but also social and environmental objectives

- three different stakeholders: including the government as well as the private sector and civil society.

Rural proofing is a key tool for government departments less familiar with rural areas

Government departments that do not deal with rural issues daily may have limited understanding of rural areas. This could leave rural areas vulnerable to ‘unresolved and conflicting assumptions and policy prescriptions’29. Rural policy is defined as ‘all policy initiatives designed to promote opportunities and deliver integrated solutions to economic, social and environmental problems’7. Consequently, rural policies frequently overlap with other policy areas, which can lead to potential conflicts in objectives and underscore the intentional need for coherence29. Governments are expected to deliver on an ever-expanding set of policy objectives, design programs, policies and regulations that will work within limited time frames in all regions. Coherent alignment is needed when one department’s policies rely upon another’s. There is also a lot to be gained from getting different government departments to see the interdependence of their policies and work on actions together.

When evidence is incomplete and unknown, it becomes particularly challenging to anticipate, analyse and thoroughly discuss the impacts of that policy. In Canada, the Rural and Northern Lens was created after noting that many of the challenges facing rural and northern communities had one commonality: a lack of forethought about the consequences of applying a ‘one size fits all’ approach to a specific policy area. Rural proofing is meant to provide assistance, and is used by ‘provincial ministries to assess the impacts of new policy initiatives or changes in existing programs before they are implemented’30. In Northern Ireland, the Rural Needs Act was implemented to safeguard the needs of rural communities and states that public authorities must ensure that policies do not disadvantage people in rural areas compared to people in urban areas31.

Rural proofing can help address policy incoherence

In 2020 the OECD cautioned that rural proofing is not fully effective if there is no coordination and integration among sectoral policies that are rural proofed3. Some policymakers tend to believe that rural proofing is not necessary because the ability to adapt policies locally is built in, meaning the policy is good as designed and rural proofing can happen when it is being executed. However, the OECD finds that often the opposite is true: the policy is not good as designed and the scope for adapting the policy is more limited at the local level19. New Zealand shaped their rural proofing policy to ‘ensure that when policymakers sit down to design the rules they take into account the unique factors that affect rural communities’32. The OECD Rural Review of England found that early engagement with policymakers during the budget committee consultative and issue-debating stages would have provided an opportunity to mitigate a number of measures with disproportionate impacts on rural areas in the budget, such as the removal of allowances for small businesses and the increase in fuel duty and changes to vehicle excise duty14. The European Commission developed a rural proofing tool because of the ‘multidimensional nature of rural areas’ and their focus on ‘social and territorial cohesion’33. They needed a mechanism to screen new EU legislation for potential impacts on rural jobs growth, development and the social wellbeing of rural people. At the same time, not all policies will require adjustments to be made if their intended purpose has little or negligible differential impact in rural areas.

Countries continue to look to rural proofing

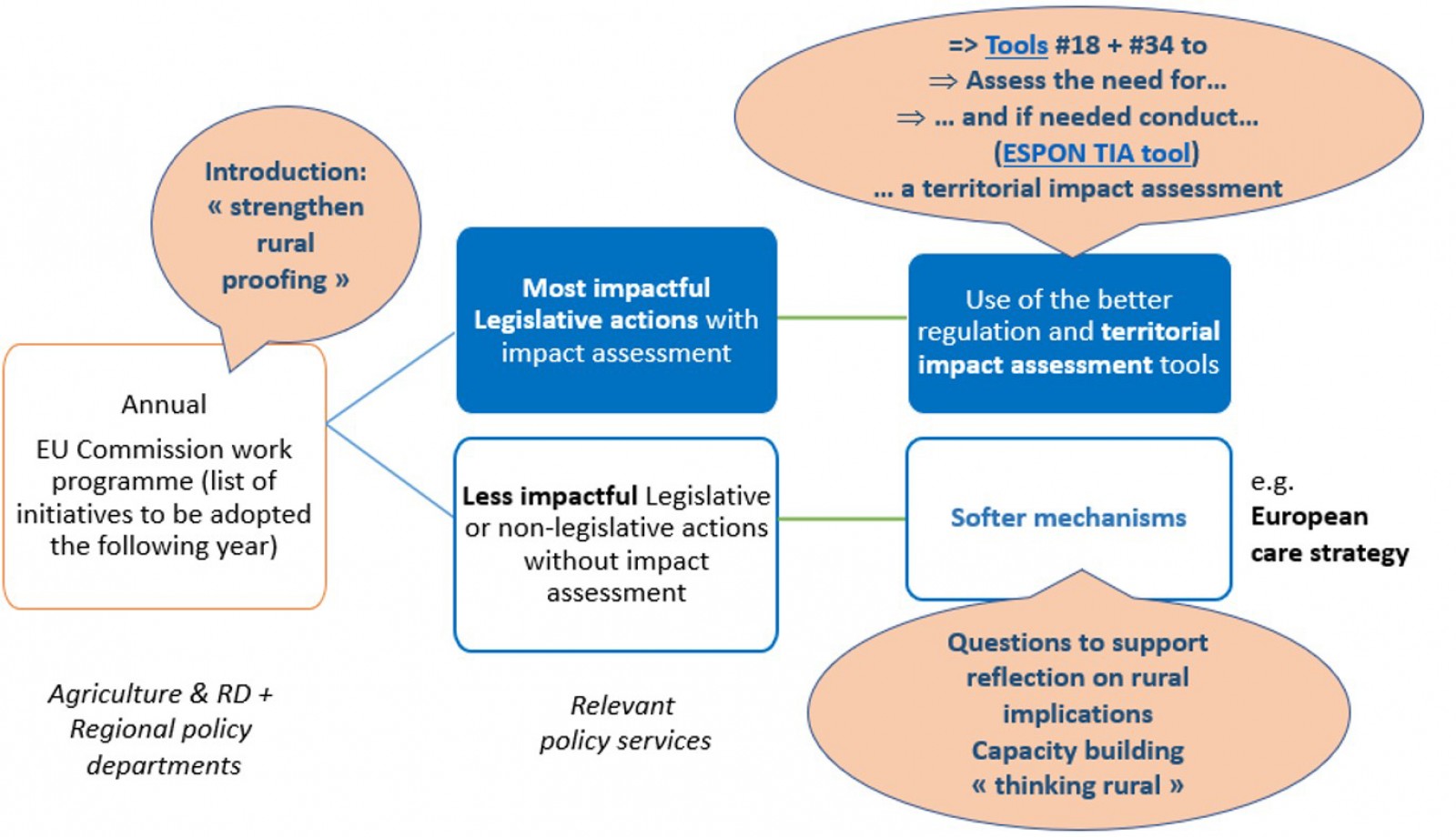

Interest in, and uptake of, rural proofing continues to grow in OECD and non-OECD countries. Indeed it continues to be a mechanism that governments turn to repeatedly to shape how policies are applied in rural areas. The European Commission recently developed a rural proofing mechanism (Fig 3) to ‘assess the impact of major EU legislative initiatives on rural areas’ and encouraged member states to do the same34. In 2022, the Rural Partners Network was conceived by an alliance of US federal agencies and launched by the Biden–Harris administration35, with multiple federal agencies at the table under the direction of the Department of Agriculture. The result is an agreement among federal agencies to improve access to government resources in their remit, staffing and tools. Another element in rural proofing is the need to be able to access ‘rural experts’ or data on rural areas to improve non-rural departments’ comprehension. In 2022, the Chilean government created a general evaluation system for all public programs to identify the ways to efficiently reach the rural population and achieve the objective of improving quality of life and increasing the opportunities of the inhabitants of rural territories (OECD Rural Proofing meeting, ‘Learning from countries with new rural proofing initiatives’, 9 June 2022).

In Germany, the policy for ensuring equivalent living conditions (gleichwertige Lebensverhältnisse), codified in the country’s basic law, evaluates the impact of policies from a territorial point of view and is meant to focus on structurally weak territories18. A new law in Spain focused on the evaluation of public policies and the creation of specialised units on public policy evaluation in Spanish independent fiscal authority, courts of auditors and social committees. As part of this process, the G100 Rural Proofing working group was created to include the rural perspective in laws36. The EU’s Long-term Vision for Rural Areas communication mandates the development of a rural proofing mechanism ‘to assess the anticipated impact of major EU legislative initiatives on rural areas’34.

The increasing demand for rural proofing mandates consideration of more flexible and reliable rural proofing mechanisms to support governments. While the evidence base is small, it suggests that some aspects of rural proofing may be more effective than others and will differ depending on the country. Given the absence of a ‘one size fits all’ rural proofing model, flexibility in the chosen approach is vital, and it is essential to invest time in experimentation to identify the most effective model. Enhancing the effectiveness of rural proofing hinges on setting explicit objectives and customising the supporting tools to align with these objectives. Employing a ‘pilot study’ approach in the initial phase aids in anticipating, responding to and learning from suboptimal outcomes in the short term. Where political commitment for rural proofing exists, leveraging it to institutionalise the practice over time is recommended. When advocating the practice to non-rural government departments, emphasis on the positive aspects of rural areas is advised, as is the exploration of diverse methods for data utilisation and collection. Models should be developed with the public servant end user in mind, ensuring alignment with time and resource constraints, policy design, and delivery modalities at the national, regional and local levels.

Figure 3: European Commission rural proofing model. Source: Rouby A, Ptak-Bufkens K (2022)33. The ESPON TIA tool is an interactive web application designed to provide a quick overview of the potential territorial impacts of EU Legislations, Policies, and Directives (LPDs) that are currently being developed: https://tiatool.espon.eu/TiaToolv2/welcome. The European Commission Better Regulation Guidelines and Toolbox outlines the principles that the Commission adheres to when creating new initiatives and proposals. Chapter 3 of the guidelines focuses on identifying impacts in evaluations, fitness checks and impact assessments. It includes Tool 18, which is dedicated to identifying all types of potential impacts, and Tool 34, which specifically encourages screening for territorial impacts. RD, rural development.

Figure 3: European Commission rural proofing model. Source: Rouby A, Ptak-Bufkens K (2022)33. The ESPON TIA tool is an interactive web application designed to provide a quick overview of the potential territorial impacts of EU Legislations, Policies, and Directives (LPDs) that are currently being developed: https://tiatool.espon.eu/TiaToolv2/welcome. The European Commission Better Regulation Guidelines and Toolbox outlines the principles that the Commission adheres to when creating new initiatives and proposals. Chapter 3 of the guidelines focuses on identifying impacts in evaluations, fitness checks and impact assessments. It includes Tool 18, which is dedicated to identifying all types of potential impacts, and Tool 34, which specifically encourages screening for territorial impacts. RD, rural development.

Rural proofing can help enhance rural health systems and optimise healthcare delivery

Delivering quality rural services in a framework of shrinking public budgets, geographic remoteness and demographic shifts presents a unique challenge for policymakers. Rural residents have shorter life spans, less healthy lifestyles and, overall, live in worse health states due to a higher incidence of chronic disease. Capacity gaps in healthcare delivery and unmet health needs were pre-existing challenges and increased the short-term costs of the COVID pandemic. Rural residents also face a wide range of threats to health status and health performance challenges, including increased poverty and joblessness1. Many rural populations face longer travel times to access rural care facilities, which face the constant threat of declining user numbers and difficulties recruiting and retaining healthcare professionals. Rural hospitals could not handle the influx of patients due to fewer specialists and less technology and capacity (eg ICU beds per capita) during the COVID pandemic37.

Rural health systems need to be strengthened and become more resilient against shocks38. The provision of health care has a strong place-based dimension necessitating a balance between costs, quality and access, all driven by population density and distance. A low volume of patients and long distances between them means that, in order to stay accessible, healthcare facilities in rural areas tend to be small and scattered1. The health of rural populations is influenced by health systems and the social determinants of health. These non-medical factors influence health outcomes, affecting health and quality-of-life risks and outcomes. According to WHO, social determinants of health are primarily responsible for health inequities – the unfair and avoidable health status differences between countries39. Without action, shrinking and aging populations in many rural communities are likely to see fewer hospital beds per head of population, higher rates of morbidity, different skill levels of, and higher demands on, local teachers and medical staff1.

Countries must invest significantly in new health facilities, diagnostic and therapeutic equipment, and information and communications technology to maintain high-quality health care and meet population needs40. Tackling the challenges of rural healthcare delivery requires understanding health issues and the structure of health systems. The OECD Principles of rural policy calls for ‘aligning strategies to deliver public services with rural policies’ and recommends assessing the impact of critical sectoral policies (including health) on rural areas and diagnosing where adaptations for rural areas are required (e.g., rural proofing)7. Rural health is a ‘key component’ of high-performing health systems and ‘inequalities in provision are more likely to happen in rural places’1.

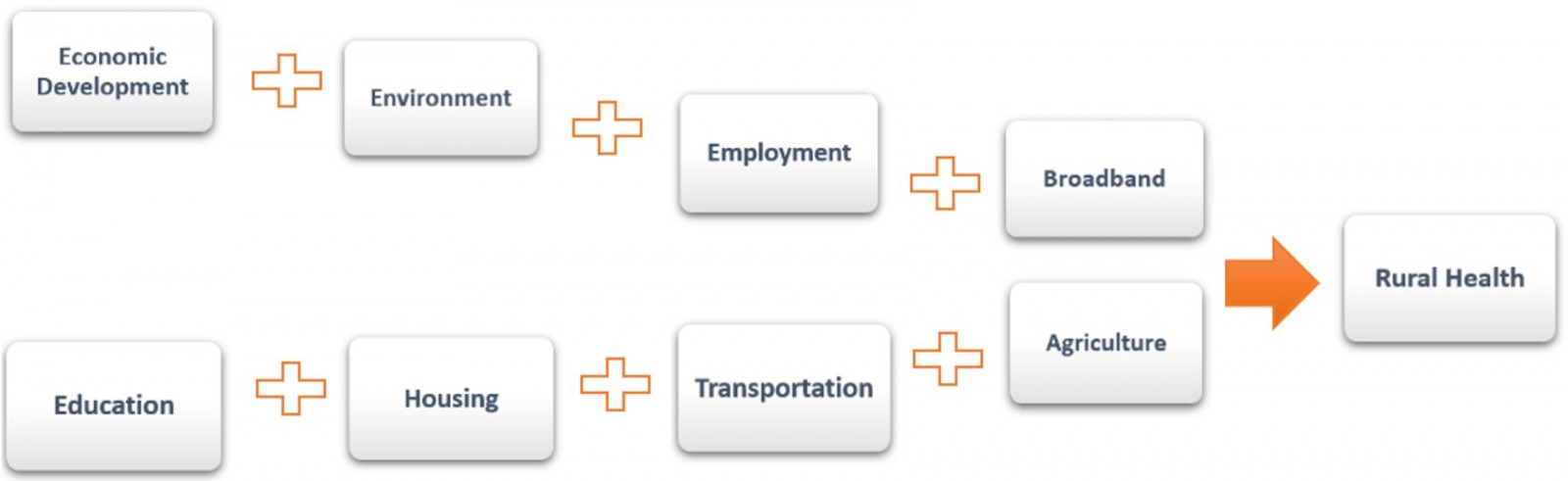

Most rural proofing rollouts have focused on all policies, regardless of department. Governments contemplating rural proofing should also consider whether they should take an all-policies or targeted approach. Efficient and effective healthcare delivery in rural areas relies directly and indirectly on the engagement of different government departments (Fig 4). There are several challenges facing the delivery of health care in rural areas, including older populations, larger distances to cover and poor connectivity (of both transport and telecommunications). Poor broadband and mobile signals hamper the delivery of services and make remote consultations challenging. Ambulance response times in rural areas tend to be longer than in urban areas, which mandates the development of more innovative approaches to deliver care.

Although health ministries bear direct responsibility for strengthening healthcare systems and expanding access, other government departments have a role to play. For example, broadband access is pivotal to ensuring that telehealth schemes can be utilised in rural places. Yet responsibility for expanding connectivity lies with non-health government departments. Similarly, other factors that drive the social determinants of health – such as transportation, education, housing access and employment – are guided by non-health-focused government departments. For these reasons, in the case of rural health, a short-term, targeted rural proofing effort could be a more appropriate starting point to enable the development of a more integrated health delivery model fostering a more comprehensive cross-government effort that brings all the relevant actors to the table. This approach is in sync with the OECD’s Rural Wellbeing Policy Framework, which highlights the importance of coordinating rural proofing across sectoral domains to optimise investments and synergies3. The COVID-19 pandemic exposed healthcare weaknesses, forcing governments to consider new healthcare spending and policies based on lessons learned. An integrated approach could yield more innovative and efficient use of public resources.

The Rural Proofing for Health workshop at the 13th OECD Rural Development Conference Building Sustainable, Resilient and Thriving Rural Places highlighted several of these issues. Representatives from Australia, New Zealand, the US, Northern Ireland, UK, Italy, Ireland and the European Commission discussed the challenges of delivering healthcare services in rural areas and adapting healthcare systems to rural needs. They also provided some insights on the steps needed to overcome these challenges and how rural proofing could help. Rural proofing produced a successful outcome in health-focused EU communication. The recently published European Care Strategy for caregivers and care receivers proposes to ensure quality, affordable and accessible care services across the European Union and improve the situation for care receivers and those caring for them41. As it belongs to the non-impactful, non-legislative category, it was rural proofed using the earlier softer tools. In the process, two departments, agriculture and employment, refined the text to include more nuanced aspects of rural regions. The process also revealed the need for more data so departments, in this case employment, can better understand the implications on rural regions33.

Figure 4: Improving rural health systems requires an integrated approach.

Figure 4: Improving rural health systems requires an integrated approach.

Different ways to increase effectiveness of rural proofing

Rural proofing also adds value in circumstances where the needs of rural people are not well understood or taken into account. The European Care Strategy for caregivers and care receivers was successfully rural proofed to add information on the lack or shortage of available care services due to long distances or limited public transport options, insufficient access to and variety of long-term care options that raised equity concerns; investments needed in connectivity to benefit from digital opportunities; and untapped employment creation potential due in part to outmigration of women33. Rural proofing is also able to galvanise local stakeholders and experts to engage and support the process. The nature of the health challenges means that a targeted approach to rural proofing will bring interdependent government departments together to agree on actions.

Nonetheless, rural proofing is shaped significantly by the way it is designed, implemented and transposed into national, regional and local policy frameworks. It is meant to support the policymaking process, but a number of elements need to be put in place to increase its effectiveness over the long term. Some key areas that could help enhance the effectiveness of rural proofing are set out in Table 1.

Table 1: Factors that could increase the effectiveness of rural proofing

| Factor | Description |

|---|---|

| Develop clear objectives and tailor supporting tools | Objectives must be clear from the start to set expectations, accurately measure success and ensure that supporting tools like the assessment questionnaires are fit for purpose. |

| Adopt a ‘pilot study’ approach – learn from suboptimal short-term results | Consider a flexible, ‘learn by doing’ model, and pilot approach where schemes can be recalibrated based on feedback. Using a trying and testing approach, permits a better definition of objectives, as well as an easier identification of barriers or bottlenecks, be they technical or political. |

| Build a model that is less dependent on political commitment over time | Take steps to encourage the development and institutionalisation of a ‘rural proofing culture’ in the public administration to embed the practice. A disproportionate dependence on political buy-in and support alone can hamper the mechanism’s sustainability over time. The natural changes that occur with political turnover, especially from an administration that is in support to one that is not, tend to affect continuity and consistent adherence to the rural proofing process. |

| Perceptions matter – change the rural narrative | Move away from the negative ‘rural needs help’ perception of rural. It is not helpful in a policy space often dominated by urban thinkers. Instead adopt a more positive ‘rural is a place of untapped opportunities’ approach. |

| Consider a targeted issue or sector approach over rural proofing all policies | Carefully considering – based on context, culture and resources – whether to adopt a whole-of-government approach or a targeted approach to rural proofing. Targeted rural proofing based on specific issues (eg climate change), public emergencies (eg disaster), or sectors (eg health) could be more manageable in the short term and provide scope for a full cross-government, all-policy effort. |

| Design the rural proofing model with the public servant end user in mind | Public servants are responsible for rural proofing, but they are often overburdened and under-resourced. Because rural proofing may involve extra steps and activities that could be seen as burdensome, involving public servants in the design process will help create appropriate models for them. |

| Encourage the collection of different types of data to support rural proofing | Improve and become more innovative with the quantitative and qualitative data collection to better support rural proofing. For example, three types of data could be helpful in rural proofing: (1) the state of rural data to provide an overall sense of rurality within the country; (2) potential impacts data to reveal potential adverse impacts of the proposed policy action; and (3) value-added data or other evidence showing how working with rural communities can help achieve a particular objective (eg addressing climate change). |

| Be flexible – there is no ‘one size fits all’ rural proofing model | The models should be developed with the governance level in mind. The implementation of rural proofing will vary at the national, regional and local levels of governance. For example, at the regional and local levels, the process could allow for more time and enable the involvement of more actors from both the public and private sectors. In contrast, there could be less time for rural proofing at the national level, allowing for less involvement of public and private actors. |

| Measure success but set realistic expectations | Robust rural proofing processes offer timely evidence of a policy's potential adverse effects on rural areas. However, rural proofing cannot force policymakers to act on the information provided. Efforts to assess and evaluate the success of rural proofing should take this into consideration. |

Conclusion

It is not surprising that rural proofing is viewed as an avenue to achieving better outcomes in rural areas and better informed decision-making. It has proved to be a valuable mechanism for determining the most advantageous way of implementing policy actions to improve the effectiveness of strategies and/or reduce their costs and adverse side effects. It can also ensure that resources are used in a more efficient way and respond more effectively to different needs. This is a significant added value, especially when governments are under pressure to use public money more cost-effectively. Rural proofing also helps governments understand how a particular strategy will affect other policy areas, making it easier to prioritise implementation and budgeting. As a general principle, rural proofing should be considered more than a checklist or box-ticking exercise. It should occur as early as possible in the policy development process, ideally before a decision to act is taken. Although it has some shortcomings, many of which are discussed in this policy report, this has not diminished its value as a key mechanism to help with the development of rural-friendly policies. Instead, it reinforces the need to support and improve the process and help countries considering new initiatives or refreshing ongoing schemes to increase the effectiveness of rural proofing.