Introduction

Continuous quality improvement (CQI) has received considerable attention within health care as a way to enhance quality of care, improve outcomes, and reduce costs1,2. CQI describes the process of improving patients’ safety, experience, and health outcomes by systematically addressing individual and organizational processes3. The Institute of Medicine has defined quality as the extent to which health care is safe, effective, involves users, is continuous, coordinated, efficient, and fairly distributed4. A review of the key characteristics of CQI in health care identified three essential elements: systematic data-guided activities, iterative development and testing processes, and designing with local conditions in mind2. Many frameworks for improvement methodologies in health care exist with some common ones including lean management, Six Sigma, Plan–Do–Study–Act cycles, and root cause analysis2,5. The central tenet across all CQI methodologies is an emphasis on using carefully chosen measures to understand the variation within a system, removing unwarranted variation, and improving system performance through a series of iterative tests of change5. Engaging physicians in CQI activities is essential to improving health care, enhancing patient and provider experience, and reducing the cost of care6.

Several factors are believed to support the implementation of successful CQI initiatives in health care, including identifying specific and measurable goals to guide action, planning processes for evaluation, measurement setting, continually assessing performance, planning changes where improvements are warranted, and refining goals as needed6-10. In a comprehensive review of published literature on contextual factors influencing CQI success, Kaplan et al found that organizational characteristics (eg size, ownership, and teaching status), organizational culture, years involved in CQI, and data infrastructure were key factors that influenced CQI success11. However, while much work has been conducted across more extensive organizational healthcare settings and environments, there is comparably little evidence about how initiatives are implemented successfully and sustainably in smaller subsets of the medical community, specifically rural and remote physician practices1,7,12,13. There have been calls for a greater understanding of the barriers and facilitators to meaningful CQI adoption and implementation in rural medical practice12.

Physicians providing healthcare services in rural and remote settings face unique challenges in engaging with CQI initiatives, given their geographic isolation and more limited access to support personnel and resources. It has also been suggested that physicians in small office settings, such as those in rural practices, may possess a limited and highly variable understanding of quality, and the heavy and stressful clinical workload with many work hours and other conflicts may potentially obstruct engagement in CQI work14,15. Deilkås et al highlight that many workplaces, including rural practice, do not recognize the need for support nor offer support to physicians who wish to engage in CQI work14.

There is a lack of understanding about how CQI may be best supported and fostered across rural medical practices, despite evidence that CQI work involvement may improve working conditions, the performance and professional fulfillment of physicians and possibly other staff14. Wolfson et al indicate that the benefits of engagement with CQI work include greater practice efficiency, patient and staff retention, and higher staff and clinician satisfaction with practice15. Small practice size, as found in many rural communities, may also be advantageous in CQI work when implemented correctly in that they mitigate the need to gain buy-in from many different participants, permit greater flexibility, and facilitate the formation of a cohesive microsystem15. Generally, there has been a lack of clarity on the best ways to engage and support rural practices in CQI initiatives.

Since 2010, the province of British Columbia in Canada has made participation in accredited continuing professional development (CPD) a revalidation requirement for all physicians to retain a licence to practice. There is no specific requirement for CQI but, because of the Cochrane Report, British Columbia prioritized quality assurance through provincial privileging, which aims to bring consistent-wide practice expectations for medical staff seeking privileges within British Columbia’s health authorities16. This report highlighted issues surrounding the quality of diagnostic imaging across several health authorities in British Columbia and raised implications for CQI among rural physician practices. During this time, several organizations supported practice and quality improvement through coaching support programs, data dashboards using electronic medical records, and coaching and mentorship programs to enable CQI.

The purpose of this study was to explore enablers and barriers to engagement with CQI and identify ways to foster rural physicians' engagement with CQI.

Methods

A rural CQI needs assessment study was designed and conducted by the University of British Columbia’s Rural Continuing Professional Development team in collaboration with the Rural Coordination Centre of British Columbia. The program is committed to improving rural patient health and the retention of skilled rural practitioners by supporting the unique learning needs of rural physicians and other rural healthcare professionals in British Columbia through high-quality and innovative CPD. A mixed-methods triangulation study design, also known as concurrent triangulation design, was undertaken, encompassing a survey questionnaire and focus group interviews to collect quantitative and qualitative data simultaneously17. The triangulation approach encompassed a one-phase design in which quantitative and qualitative methods were administered concurrently but separately, during the same timeframe, with equal weighting, and intended to complement each other. During the interpretation stage, the quantitative and qualitative data were merged so the research team could triangulate how the results related to and informed each other. This study was also informed by the Model of Understanding Success in Quality framework11. The framework outlines a range of contextual factors/domains that can influence the effectiveness of CQI activities, including the team, microsystem, supports, organization, and environment. By tracing the relationships between factors, the model allows for an in-depth understanding of how context impacts the effectiveness of CQI and provides a framework for guiding application and research11.

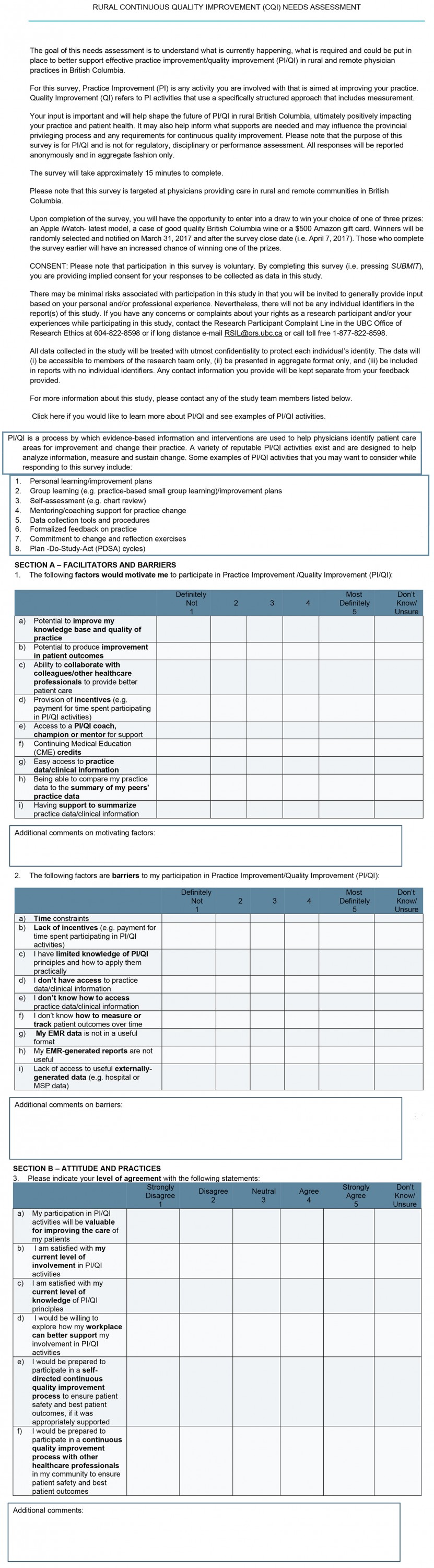

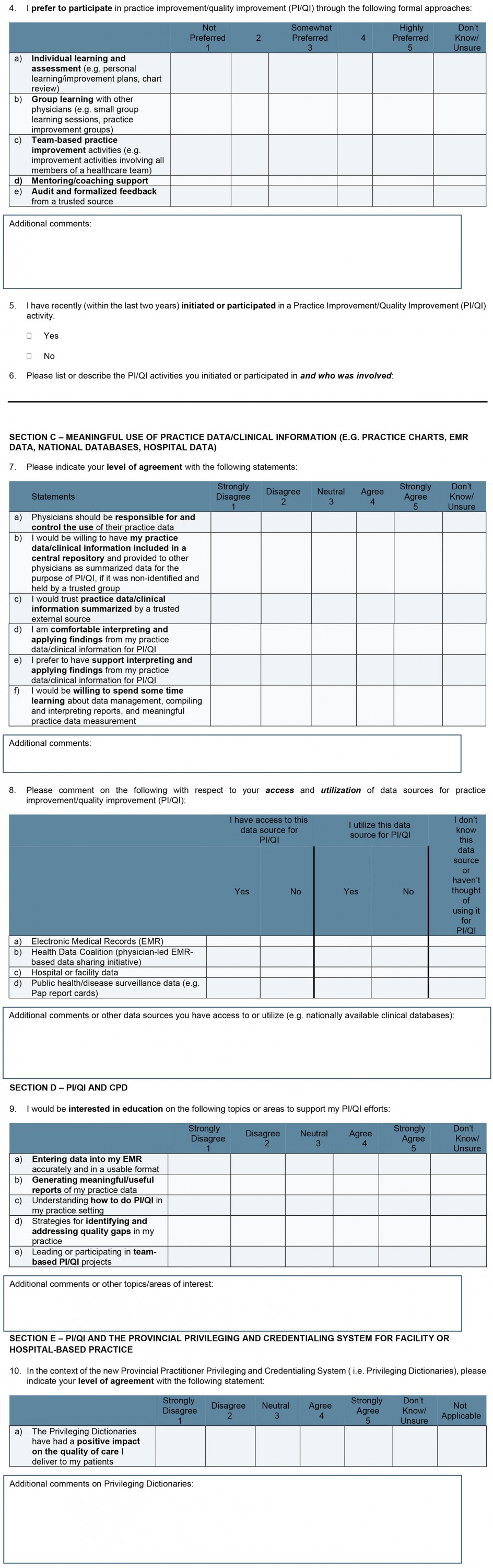

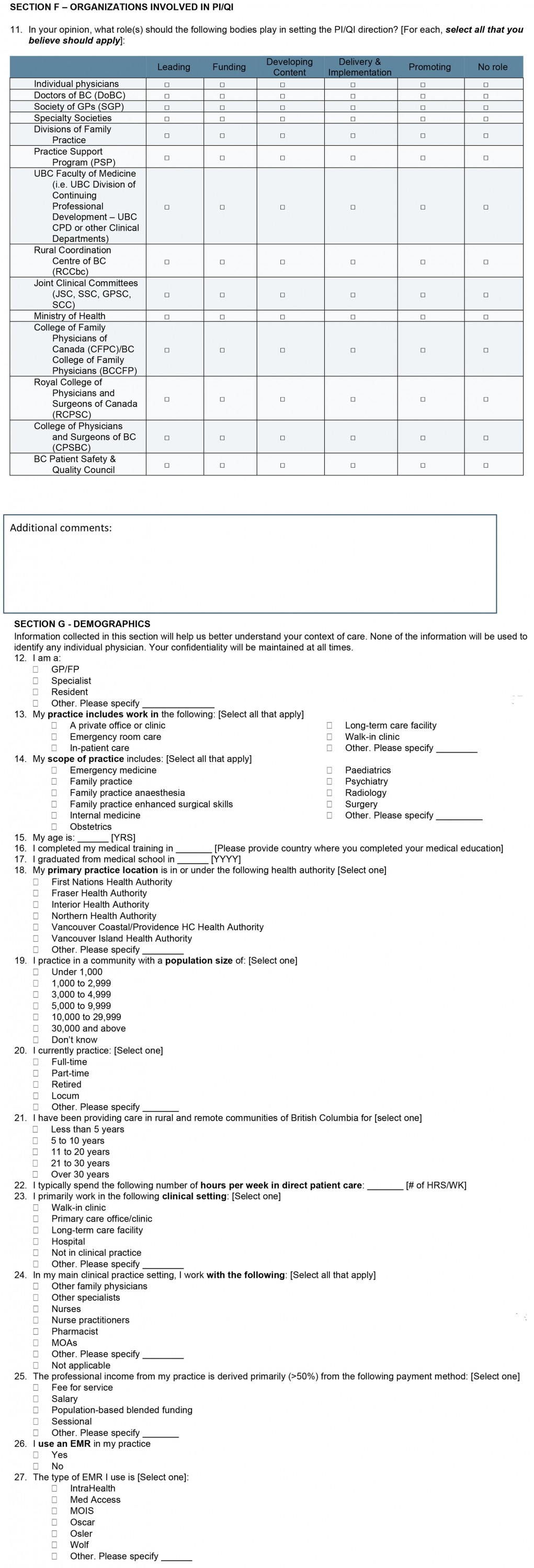

A 27-item, web-based survey comprising Likert-style, closed-ended item types (1, ‘definitely disagree’ to 5, ‘definitely agree’) and open-ended questions was distributed to family physicians and specialists providing care in rural and remote communities of British Columbia. To ensure study participants were familiar with CQI concepts, definitions and examples of CQI activities were included at the beginning of the survey (Appendix I). The survey was distributed using the FluidSurvey platform between March and May 2017 with the assistance of the Doctors of BC and the Northern and Isolation Travel Assistance Outreach Program. Survey questions were reviewed for face and content validity by a project advisory committee, including rural physician representatives, and a draft version of the survey was piloted with a small sample of rural physicians. Survey questions covered facilitators and barriers, attitudes and practices, meaningful use of practice data/clinical information, practice improvement/quality improvement (PI/QI) and CPD, PI/QI and the provincial privileging and credentialing system for facility or hospital-based practice, organizations involved in PI/QI, and demographics (Appendix I). Survey responses were analyzed using SPSS v17.0 (IBM Corp; https://www.ibm.com/products/spss-statistics) and descriptive statistical analyses. Likert-style questions were collapsed and analyzed using a three-point Likert scale (1, ‘disagree’ to 3, ‘agree’). Cross-tabulations and χ2 statistical analyses were conducted to examine the effect of demographic variables (eg region, compensation model, gender, and duration in practice) on item responses.

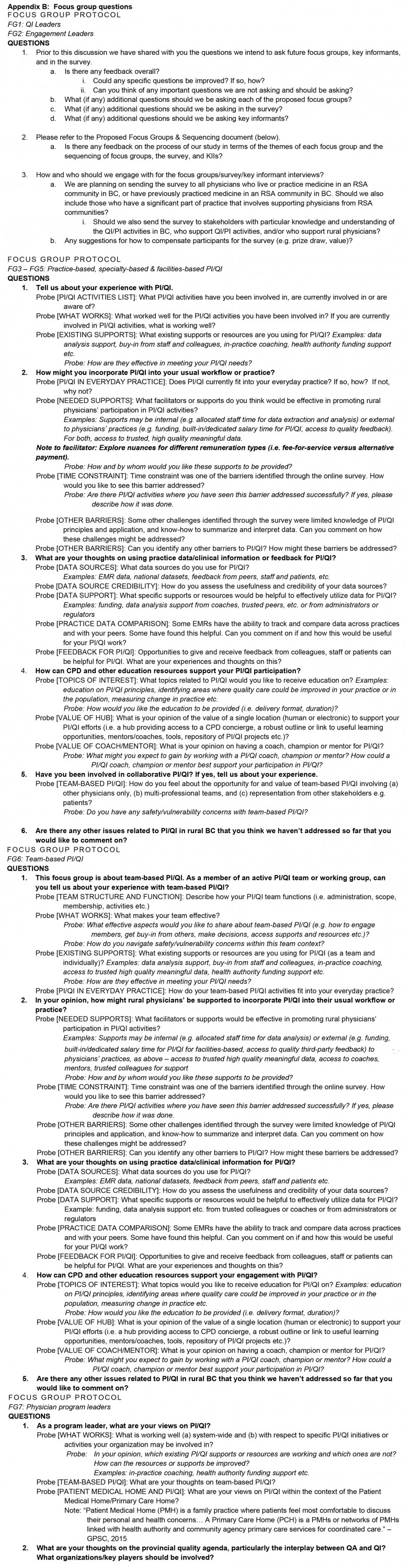

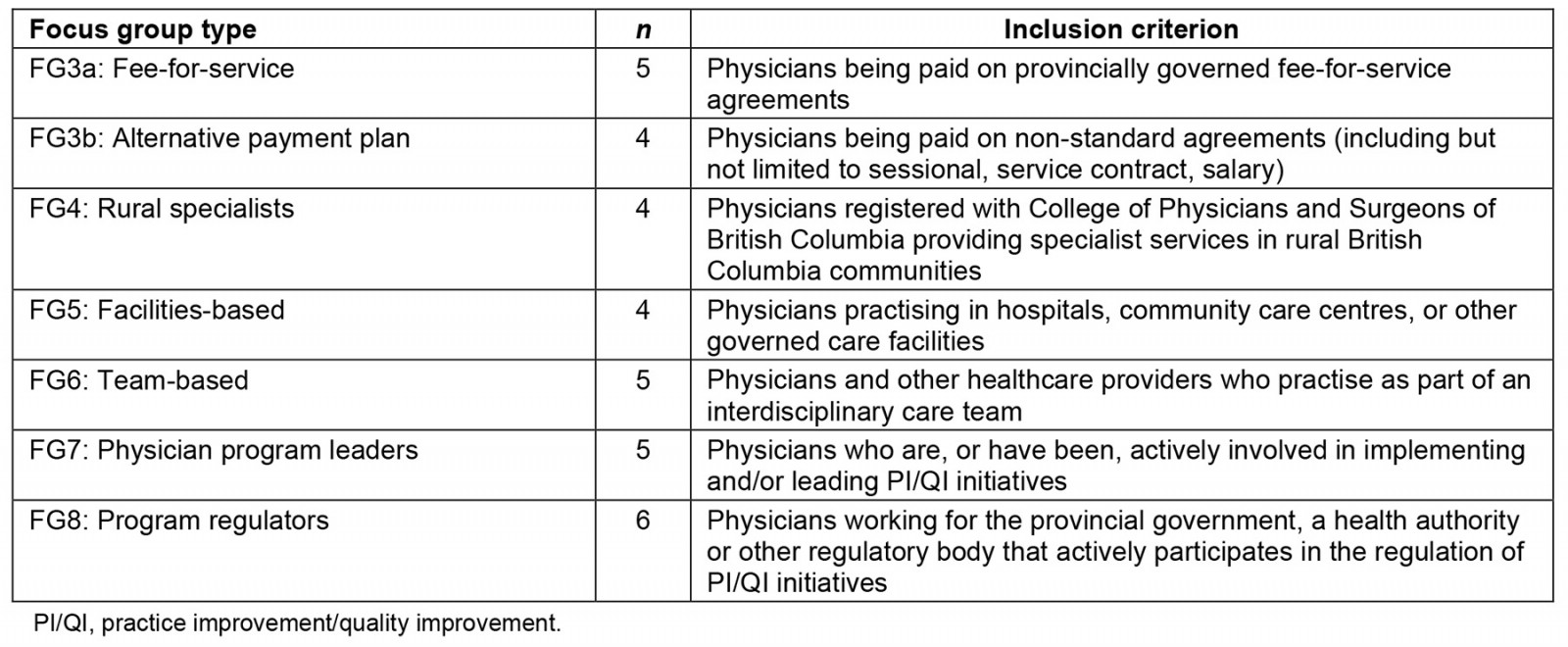

Focus group interviews were conducted between September 2017 and January 2018 and included seven distinct focus groups comprising representatives from the following groupings: fee-for-service (FFS), alternative payment plan (APP), rural specialists, facilities-based, team-based, physician program leaders, and program regulators. Modified focus group question scripts were used for each group, and respondents received these questions in advance (Appendix II). Focus groups were 90 minutes in length and conducted using the WebEx web-conferencing system and/or a teleconference dial-in option. Responses were recorded and transcribed, and data were tabulated, summarized, and analyzed for patterns or emergent themes. Researchers created a codebook via iterative development, and transcripts were coded independently by research team members and then discussed and condensed into thematic categories. NVivo v11 (Lumivero; https://lumivero.com/products/nvivo) was used to organize and group data and apply units of analysis. The study was undertaken with guidance from an advisory committee, which included broad stakeholder representation from members of the target audience, rural medical educators, representatives from British Columbia health authorities, Doctors of BC, and the Rural Coordination Centre of British Columbia.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was received from the Behavioural Research Ethics Board, University of British Columbia, #H16-01508.

Results

Survey results

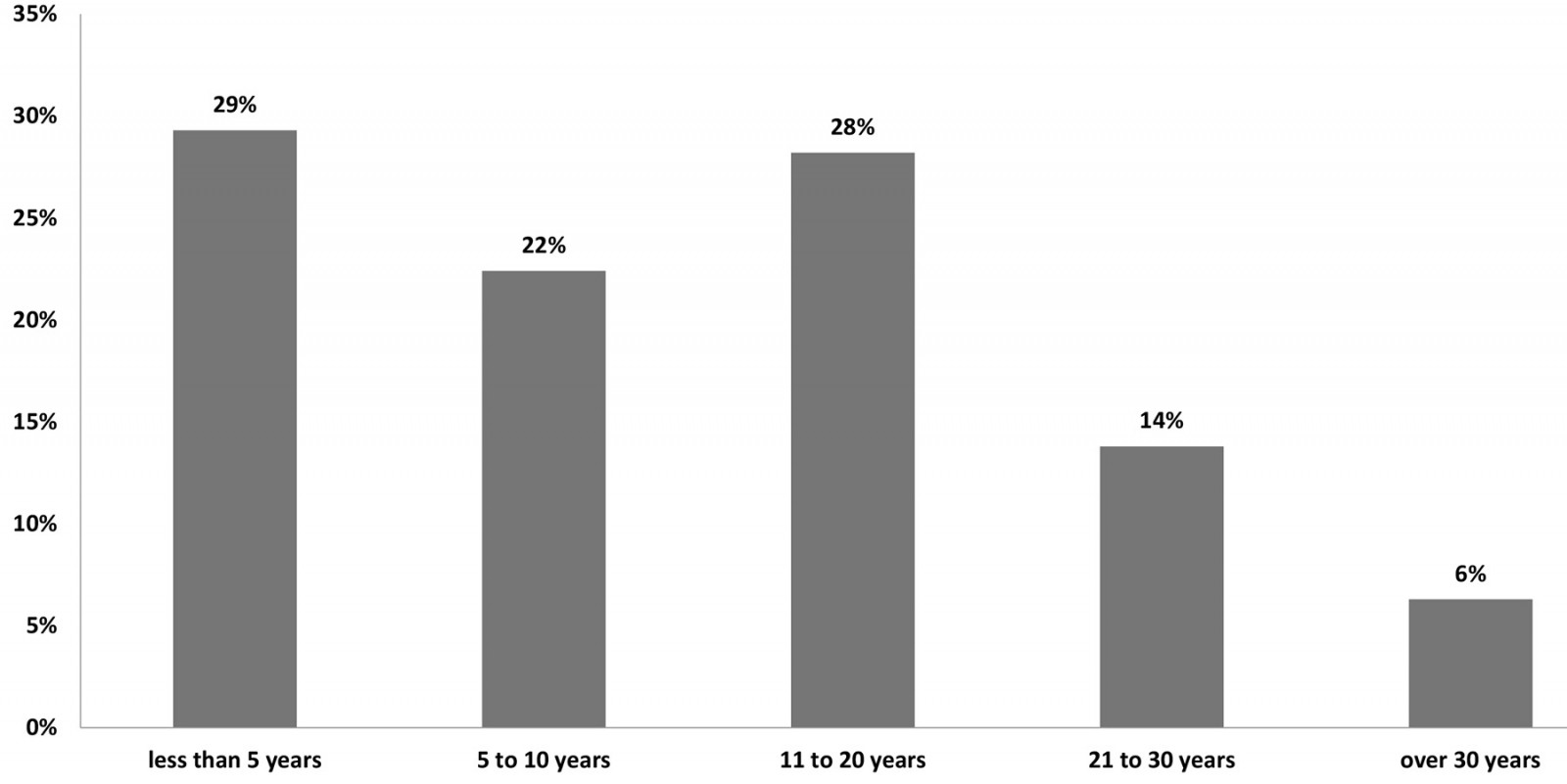

A total of 1584 physicians were sent requests to complete the survey, and a total of 299 responses were collected, which resulted in a response rate of 19%. Survey respondents' characteristics suggest that a representative sample of British Columbia rural physicians responded based on practice type, clinical setting, electronic medical record (EMR) usage, and community of practice. A majority (n=106) of the respondents reported they primarily practised as family physicians (FPs) or GPs, with 58 respondents reporting to practise as a specialist. Over 71% of respondents completed medical training in Canada, whereas 29% were international medical graduates. Twenty-nine percent of respondents graduated in the previous 5 years and 20% graduated more than 20 years ago (Fig1).

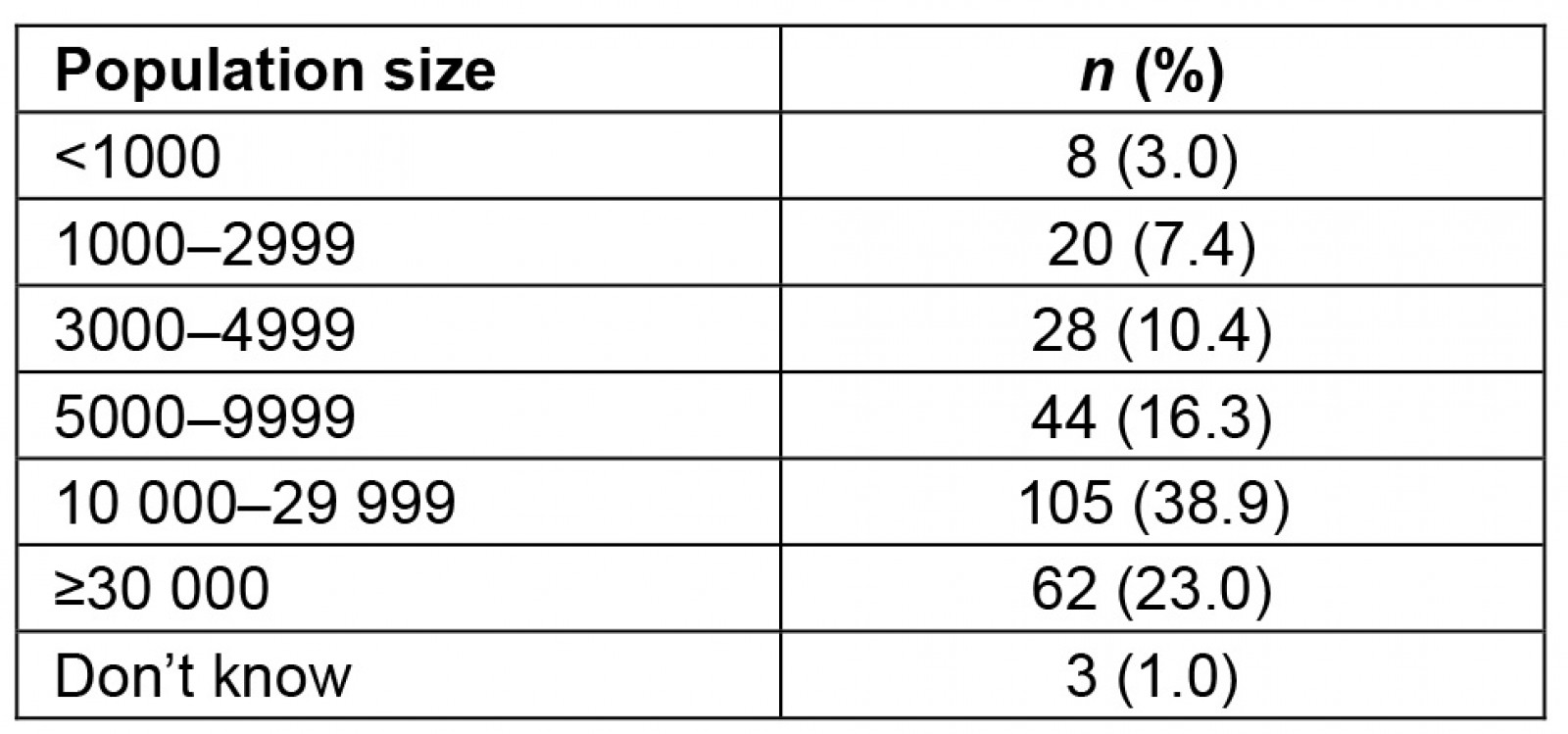

The majority of respondents (76%) indicated they practised in a community with a population of less than 30 000 (Table 1) and a majority (70%) reported working in a rural or remote community of British Columbia for more than 5 years.

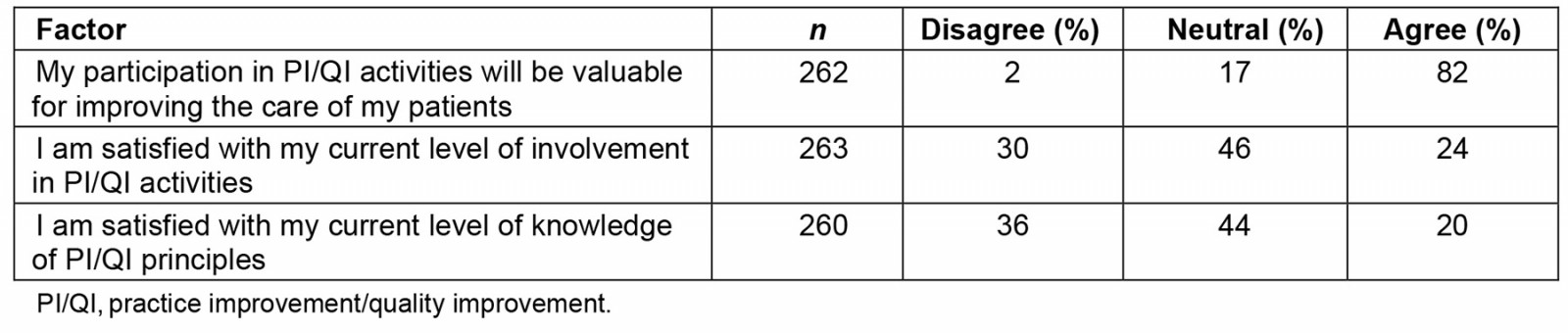

A majority of respondents (66%) indicated their scope included ‘family practice’, followed by ‘emergency medicine’ (41%), with 61% reporting they primarily worked in a ‘primary care office or clinic’ and 28% primarily practising in a hospital. A majority (77%) also reported working within a ‘group practice setting’ with other physicians, and 80% reported that their primary source of professional income came from ‘fee for service’. Eighty-five percent (85%) of respondents used an EMR to do clinical practice, with the most common platforms being MOIS (18%) and Med Access (18%), followed by IntraHealth (14%), Oscar (9%), Wolf (9%), and Osler (7%). Less than half of respondents (42%) indicated that they had participated in a CQI initiative within the previous 2 years and a majority (82%) agreed that their participation in CQI activities was valuable for patient care. A smaller proportion indicated satisfaction with their current level of involvement (24%) (Table 2).

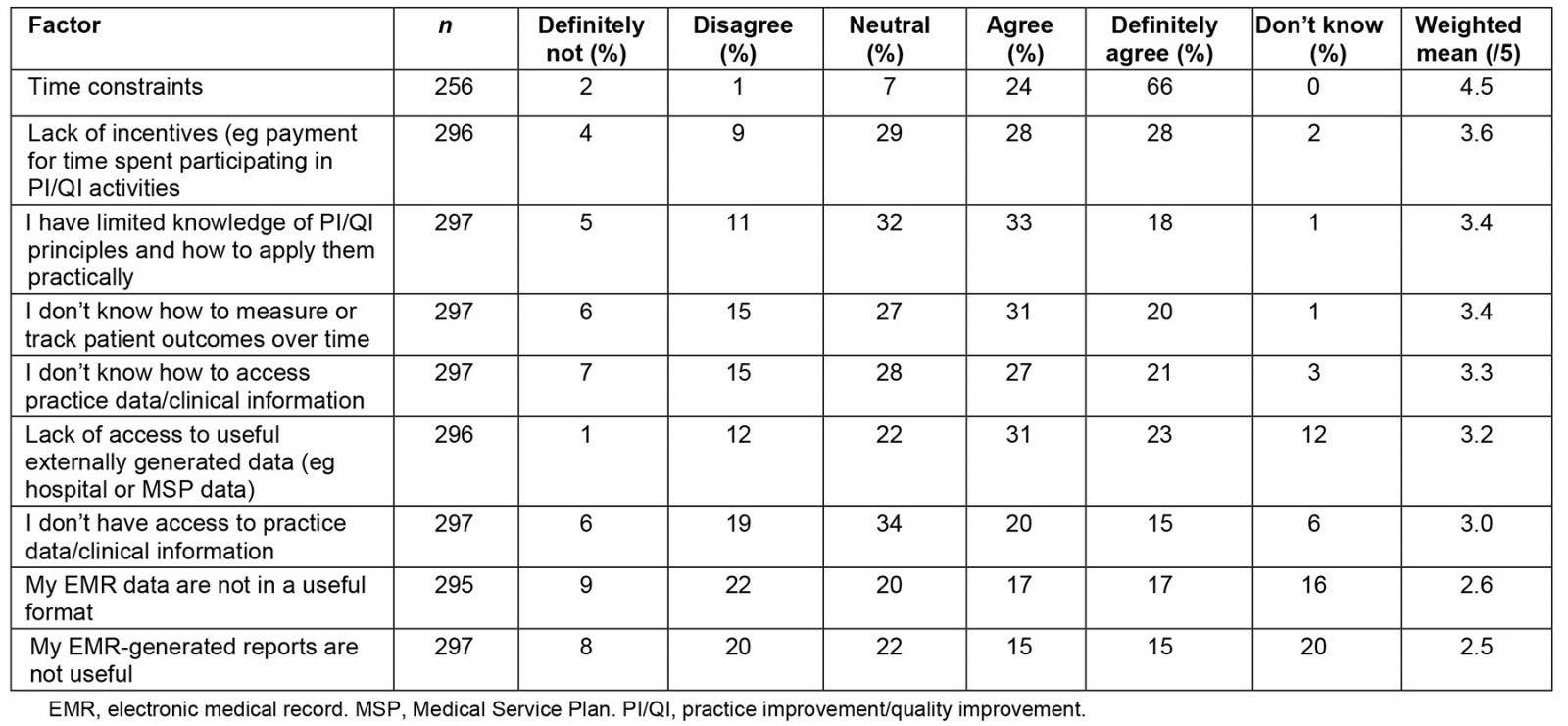

A ‘lack of time’ was the most frequently cited barrier among 90% of respondents (Table 3). Other key barriers to CQI participation identified by over half of respondents included lack of access to useful externally generated data (62%), lack of incentives (58%), limited knowledge of CQI principles and application (52%), and limited knowledge of how to track patient outcomes over time (51%). Interestingly, questions about access and/or use of data sources for CQI were answered with ‘I don’t know’ much more frequently than other questions.

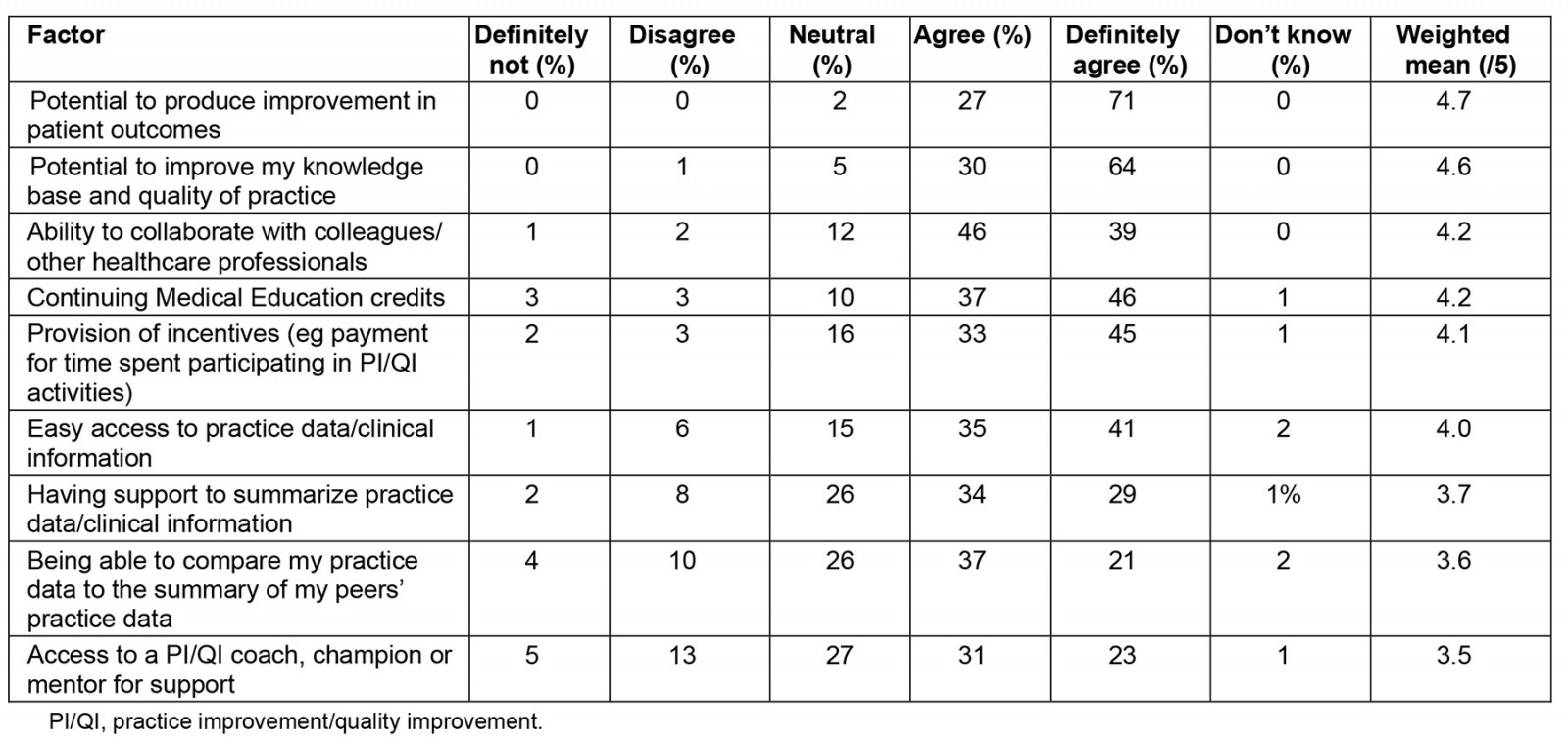

GPs/FPs were more likely than specialists to indicate that ‘access’ to EMR-type clinical data (χ2(2)=15.95; p<0.01) and the ‘usability’ of available EMR data (χ2(2)=7.00; p<0.05) were barriers to CQI. Respondents in smaller communities were less likely to utilize public health/disease surveillance data for CQI than their colleagues in larger centres (χ2(1)=15.47; p<0.01). Further, international medical graduates were more likely to indicate that a lack of knowledge regarding CQI principles was a barrier to their involvement than those trained in Canada (χ2(2)=6.76; p<0.05). More than 80% of respondents agreed that the following factors were motivators to their participation in CQI activities: potential to produce improvement in patient outcomes, potential to improve knowledge base and quality of practice, ability to collaborate with colleagues/other healthcare professionals to provide better patient care, and continuing medical education (CME) credits (Table 4).

Respondents were quite favourable (‘agree’ and ‘definitely agree’) to the ‘provision of incentives’ and ‘easy access to practice data or clinical information’ (78% and 76%, respectively). Other items receiving very favourable ratings (‘agree’ and ‘definitely agree’) included ‘access to a PI/QI coach, champion or mentor for support’ and ‘being able to compare practice data with summary of their peer’s data’ (54% and 58% of all respondents agreed, respectively) (Table 4). Chi-squared analysis of CQI enablers and demographic characteristics showed that GPs/FPs were more likely than specialists to agree that provision of incentives was a motivator to CQI participation (χ2(2)=8.50; p<0.05). Further, Canadian medical graduates were more likely than international medical graduates to agree that the provision of CME credits was an effective motivator for CQI engagement (χ2(2)=6.26; p<0.05).

Figure 1: Years since graduation of rural physician survey respondents.

Figure 1: Years since graduation of rural physician survey respondents.

Table 1: Population size of community of practice (n=270)

Table 2: Current attitudes and agreement with practice improvement/quality improvement capability

Table 3: Barriers to participation in practice improvement/quality improvement activities

Table 4: Motivators to participation in practice improvement/quality improvement activities

Focus group results

Each focus group interview had four to six participants, for a total of 33 respondents (Table 5).

Table 5: Focus group inclusion criteria

Focus group respondents described various CQI initiatives they currently engaged in, as well as their level of satisfaction with such initiatives, and level and quality of CQI initiatives available. A significant motivator to engaging in CQI activities was the ability to collaborate with colleagues and receive useful and actionable feedback regarding practice habits and areas of improvement. One important aspect of this was the ability to reflect upon one’s practice-level data, compare with one’s colleague or with data from their community/region/province, and thereby gain a better sense of what is currently working and what could use improvement. These viewpoints were also supportive of survey responses as over 80% of survey respondents agreed that a key motivational factor for participating in CQI included the potential to produce improvement in patient outcomes, improve knowledge and quality of practice, and collaborate with colleagues/other healthcare professionals to provide better patient care. Respondents also highlighted the importance of the CQI process occurring in a safe environment focused on learning and improvement.

As a physician we often expect perfection from ourselves, and so being in a place where we can say we’re not perfect but we’re getting better is so important, … it’s actually okay if we’ve not made it and way better to figure out why we’ve not made it than to just ignore the fact that we’ve not made it. (FG7: program leader respondent)

The types of initiatives and involvement described were diverse and influenced by the context of one’s practice. Practice and clinical support resources such as ‘practice coaches’ were frequently described. Intercollegial or interprofessional practice rounds, or ‘morbidity and mortality’ type discussions, were common examples. Other care team members were considered vital in CQI initiatives, including allied healthcare providers, administrative staff, and patients. A key facilitator to CQI engagement was a ‘team-based’ approach that could occur in the context of interprimary care providers and coordinated care models. This sentiment was also supported by survey results in which most respondents reported a preference for team-based CQI activities (63%), especially among GPs/FPs and those practising in smaller population communities.

We have real in-time quality improvement in that we don’t work in silos in our clinic. We’ve actually structured the clinic so that we can have maximum crossover between the different providers. (FG6: team-based respondent)

Despite the array of currently available CQI initiatives and resources and the seemingly high level of current engagement, nearly all respondents indicated room for improvement. Areas in which CQI professional development was considered a priority encompassed ‘social determinants of health’, including ‘mental health’, understanding ‘adverse childhood experiences’ and ‘culturally safe care for Indigenous patient populations’. Another crucial professional development area was the effective use of CQI resources/tools.

I think from an educational perspective, there’s some formal training for physicians to learn how to use QI, [but] I think very few physicians will go on that option. I think most of where the education needs to be based is on trying to teach physicians when they do take projects, it’s just coaching them on how to use different tools effectively. (FG8: program regulator respondent)

A number of barriers and enablers to engaging with meaningful CQI initiatives were identified, including time, compensation models, knowledge, sustainability and accountability, and regulatory authority approaches. Time constraints were a prevalent barrier to engagement with CQI initiatives and the most frequently cited barrier among over 90% of survey respondents. Between clinical duties, personal needs, and the diverse array of other responsibilities, carving out the time to engage in CQI was challenging.

I mean time is always a factor in these things and a lot of times we’re so busy in what we do we just want to escape from what it is we’re doing to give ourselves a break from that which is causing us immense stress. (FG8: program regulator respondent)

Many respondents indicated that having CQI directly integrated into their workflow would greatly improve their engagement and satisfaction.

Having it consciously scheduled into your practice clinical routine I think are keys to making it just a part of your everyday practice versus as a chore. (FG3a: FFS respondent)

Time was also connected to and influenced by compensation models, with traditional FFS payment inhibiting time commitment to engage in non-compensatory CQI activities. Respondents discussing APP models (eg salary, sessional, service contract) did affirm they were better able to allocate resources (including time and energy) to other areas, including CQI.

I do think the APP model allows for quality improvement well. You can initiate quality improvement trials which may or may not be successful without fear for the bottom line and I think that opens up a lot of freedom to be able to try things out … I think the APP model does support that kind of quality improvement. (FG3b: APP respondent)

Lack of knowledge was another barrier to meaningful CQI engagement, including how to identify areas of potential need for improvement and develop ways to address these areas. Survey respondents reported that the most popular topics for CPD included identifying and addressing quality gaps in practice (85%), generating meaningful/useful reports from practice data (80%), understanding how to do CQI (76%), and being able to accurately enter data into their EMR in a usable format (67%). Notions of sustainability and accountability were also discussed, with focus group respondents identifying the need for support to foster the longevity of initiatives and ensure that newly acquired skills, competencies, or other practice improvements were not lost. These findings also reflected survey responses – while survey respondents identified the potential benefits of CQI and were interested in incorporating it into their practice, a majority reported not having the tools and know-how to do so.

I think all of us when we begin on our practice improvement projects, we all have the best of intentions to complete it but six months rolls around and it just hasn’t and it’s not that we don’t view it as important, it’s how do we continue to make it a priority throughout the course of our regular working day and that’s the challenge. (FG3a: FFS respondent)

Respondents reported that being accountable to colleagues and others engaging in similar CQI projects was a powerful tool for enhancing CQI success. They also indicated that having a local CQI champion responsible for fostering these kinds of initiatives could encourage greater adoption.

One of the most important aspects of this process to me is the relationship between the trusted advisor or mentor and a physician to hold the physician accountable for some of the quality improvement projects that they’re doing. (FG8: program regulator respondent)

Physician respondents discussed the need to separate practice assessment from quality improvement and enable a greater culture of independent CQI in which quality improvement could be pursued in a safe, non-punitive environment. In this regard, regulatory authorities were identified as a potential challenge as such organizations approach quality with a quality assurance lens rather than an improvement lens. When this kind of quality check is conducted outside a safe, non-punitive environment, it risks interfering with meaningful practice improvement.

Another key thematic category from the focus group analyses was the significance of technologic systems and data availability to engage in quality improvement. Key emerging subthemes included accessibility, EMRs, support, and data quality. Respondents agreed that having access to practice-level and regional/provincial-level data was invaluable. Ideally, access to readily available, helpful, and intuitive data would be most beneficial. However, aside from data that might be available through an EMR system, there were reported experiences of challenges and difficulty in accessing data from other sources. Respondents felt most of the data they could access could only be obtained through a laborious self-initiated process. As such, respondents indicated a preference for data that was pushed to them and which they could decide whether to use.

It needs to be made easy and with that push aspect once the clinical question is asked in terms of easily accessing the data and then that sense of collaboration with others to discuss and review and talk about strategies. (FG3a: FFS respondent)

Respondents reported that, despite some drawbacks to EMR-type data systems (namely, lack of interoperability and the burdensome task of data entry), these did provide a potentially important source of practice-level data. However, it was noted that a large subset of physicians either did not know how or did not have time to extract data from their EMR systems in a format that would lend itself to any kind of meaningful CQI.

Very few physicians know how to meaningfully pull the data out of their local EMR and run reports, do run times, look at any indicators … I think really being intentional about supporting physicians using those data sources and making the usability of the local EMR’s better at being able to run the reports is quite key. (FG7: program leader respondent)

Another key way to enable and empower rural physicians in CQI engagement was through better data support, such as dedicated personnel to assist with data management, entry, processing, analyzing, summarization, and extraction. The quality of the data was also identified as important, with critical criteria including parameters/consistency, applicability/context-dependence and the type of data collected. Survey respondents also indicated strong support (82%) for individual physician ownership over practice-level data; a majority reported a preference for more significant support in interpreting and applying their data (64%).

Discussion

This study aimed to explore enablers and barriers to engagement with CQI and identify ways to foster the engagement of rural physicians. The majority of respondents reported a positive attitude towards participating in CQI activities, agreed that participating in these activities would be advantageous for improving the care of their patients, and indicated a strong desire to learn more about CQI. A majority also showed strong support for exploring ‘how their workplace could better support their involvement in CQI activities’, as well as ‘their readiness to participate in a self-directed or team-based continuous QI’. However, a low percentage of respondents were satisfied with their current knowledge of CQI principles or their current level of involvement in CQI activities, with only half having initiated or participated in any CQI activity in the preceding 2 years. Several barriers were identified, with ‘time constraints’ being the most frequently cited by a large majority. Deilkås et al also found that physicians were highly interested and wanted to participate in CQI work. However, active participation was significantly related to their work-hour schedule's designated time for quality improvement14. Physicians with designated time participated substantially more. When the time was designated, 86.6% of the physicians reported participation in CQI, compared to 63.7% when the time was not specifically designated14. Similarly, Wolfson et al found that physicians in small-to-moderate primary care practices in the US faced comparable challenges in implementing CQI initiatives, including time constraints, cost of activities, limited resources, small staff, and inadequate information technology systems15.

In the present study, incentives emerged as an essential motivator for respondents’ participation in CQI, with a majority indicating ‘provision of incentives’ as a motivator for CQI practices. These incentives may take various forms, including creating the space (eg time), being better equipped (eg training, access to data) for CQI activities, and trying to streamline CQI into existing workflow. CME credits were also identified as an important motivating factor. Further, having CQI activities embedded within an interdisciplinary, team-based approach strongly motivated our survey and focus group respondents. This is a well-known contributor to a thriving CQI culture6,7, so tailoring opportunities to engage in meaningful CQI with multidisciplinary colleagues may be vital to ensuring the success and longevity of initiatives in rural communities. Wolfson et al also found several facilitators to CQI engagement, including the designation of a practice champion, the cooperation of other physicians and staff, and the involvement of practice leaders15. Like our findings, financial incentives were not found to be a significant motivating factor in the study by Wolfson et al in which physician respondents reported stronger intrinsic professional motivations towards CQI engagement in order to increase performance levels15.

Since microsystem-level attitudes, motivation, and CQI capabilities are central to CQI success, it will be critical to provide physicians with the support, tools, and resources required to translate their desire and amenability to CQI into a practical and sustainable CQI culture9,10. One of the significant tools highlighted in our investigation was ‘practice data’. Respondents indicated that the use of such data would be beneficial to CQI initiatives, yet respondents also indicated a lack of knowledge about how to access and use or interpret this kind of data. This suggests a potentially beneficial avenue for the development and implementation of support systems and personnel dedicated to the collection, interpretation, and appropriate dissemination of this kind of data, which has previously been suggested to be beneficial to physician CQI6,11.

The study findings suggest a strong willingness and motivation among rural physicians to participate in CQI. Although respondents were aware of the potential benefits of CQI and were interested in incorporating it into their practice, they did not have the tools or know-how to translate CQI principles and practice into action, which presented an opportunity for continuous learning and development. Shojania et al suggest CPD can play an essential role in imparting concepts and methods of CQI to physicians, with better outcomes realized when they receive individualized coaching, performance data, or process improvement tools, such as educational material for patients and decision support for clinicians18.

The findings of this needs assessment study have been used by a British Columbia Joint Standing Committee on Rural Issues to advocate for further support of rural physicians with CQI initiatives. The Joint Standing Committee receives funding from the British Columbia Ministry of Health and Doctors of British Columbia and is a critical group in British Columbia that oversees rural health issues on behalf of rural physicians. Fundamental changes that have emerged include more funding for new family physician payment models that reimburse time commitments to CQI work, increased funding for more accredited CPD practice improvement programs, including coaching and mentoring, and concierge services for rural physicians. The concierge-type support service provides more significant support to rural physicians interested in undertaking CQI in their practices by matching the most appropriate programs, tools, or initiatives to meet their needs.

A key limitation to the study findings reported here may be the respondent sample size. However, the survey respondents' sample was representative of the general demographic characteristics of British Columbia, Canada's rural physicians based on type of practice, clinical setting, EMR usage, and location. Overall, enablers to greater rural physician participation in CQI appear to include better support on how to initiate and sustain CQI activities, embed these initiatives within the context of rural practice, manage time constraints, and translate trusted practice data into meaningful change. Future research that evaluates practical approaches for supporting and fostering rural physician engagement in CQI activities would contribute to a better understanding of ways to promote implementation and sustain CQI in rural medical practice.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Dr Dilys Leung and Loulou Chayama, who contributed to data analysis and writing.

Funding

This study was funded by the British Columbia-based Joint Standing Committee on Rural Issues.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.