Dear Editor

Human papillomavirus (HPV) can cause cancer. It is the most prevalent sexually transmitted infection in the US, with most adults exposed to HPV in their lifetime1. Although HPV, and therefore HPV-associated cancers, can be prevented by a vaccine, uptake of the HPV vaccine has been uneven across the country2. This is especially true in rural regions, which have recently shouldered a growing burden of HPV-associated cancer.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted cancer prevention and control systems, causing over 100,000 missed cancer diagnoses3, HPV-associated cancer incidence was rising in rural America4. In fact, incidence of rural cancer was growing faster than urban incidence, widening the rural–urban gap4. However, the existing evidence fails to adequately describe the burden of HPV-associated cancer in rural America. First, the rural–urban disparity of HPV-associated cancer incidence, as reported in most research, is in fact reporting disparities between metropolitan (metro) and non-metro counties4. This classification ignores heterogeneity within non-metropolitan populations and may be masking the excessive burden in small, rural communities relative to larger, urban communities. Second, most of the research has focused on disparities in incidence of and mortality from HPV-associated cancer, but given less attention to rural–urban disparities in mortality where HPV-associated cancer was not the underlying cause of death but a contributing factor5.

Methodology

To understand the burden of HPV-associated cancer in rural communities beyond the pandemic, I analyzed the latest Surveillance, Epidemiological, End Results (SEER) incidence and incidence-based mortality data spanning the years 2000–20216,7. The incidence-based mortality data includes deaths where HPV-associated cancer was the underlying cause of death and deaths where HPV-associated cancer was a contributing factor or disease condition on the death certificate5,7. Using the definition from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention via SEER*Stat, I accessed data for all cancers attributed to HPV (Supplementary material 1). This included cervical and certain types of oropharyngeal, anus, rectum and genital cancers4. For this brief analysis, I studied two outcomes: age-adjusted cancer incidence rates and age-adjusted mortality rates (of any cause among people diagnosed with HPV-associated cancer). All rates were restricted to contiguous SEER state registries (Supplementary material 1) and reported by 100,000 population. Each rate was stratified by the Rural Urban Continuum Code classification system (metro=1–3, urban=4–7, rural=8–9). Using the Tiwari correction method, I then reported rate ratios to separately compare rural rates with urban and metro rates8.

Results

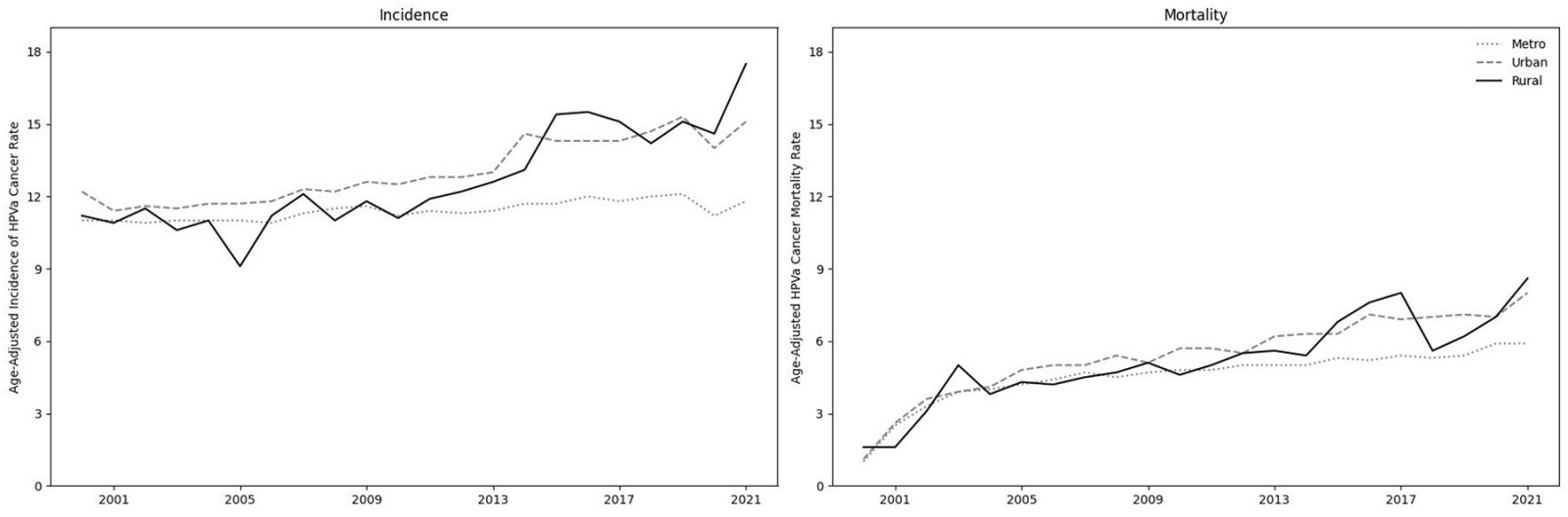

Figure 1 reports the trends in HPV-associated cancer incidence and mortality for rural, urban and metro populations.

Figure 1: Age-adjusted incidence rate (per 100,000 population) of HPV-associated cancers and the age-mortality rate (per 100,000 population) of HPV-associated cancers. Using the Rural Urban Continuum Codes (RUCC) system, rates are aggregated as metro (RUCC 1–3), urban (4–7) and rural (8–9).

Figure 1: Age-adjusted incidence rate (per 100,000 population) of HPV-associated cancers and the age-mortality rate (per 100,000 population) of HPV-associated cancers. Using the Rural Urban Continuum Codes (RUCC) system, rates are aggregated as metro (RUCC 1–3), urban (4–7) and rural (8–9).

Incidence

The HPV-associated cancer incidence rate in 2019 was significantly higher in rural (rural rate 15.1, 95% confidence interval (CI) 13.1–17.2) than metro (metro rate 10.6, 95%CI 10.4–10.7; rate ratio 0.8; p=0.0018) counties, but similar to the rate in urban counties (urban rate 15.3, 95%CI 14.7–16.0; rate ratio 1.02; p=0.85). Although the decline in 2020 was consistent across metro, urban and rural regions, in 2021 the rural incidence (rural rate 17.5, 95%CI 15.4–19.9) was significantly higher than both urban (urban rate 15.1, 95%CI 15.4–15.7; rate ratio 0.86; p=0.03) and metro (rate 11.8, 95%CI 11.6–11.9; rate ratio 0.67; p<0.001) rates.

Mortality

In 2019 and 2020, the HPV-associated cancer mortality rates did not differ between rural–urban or rural–metro counties. However, although rates remained similar between rural and urban counties, in 2021 HPV-associated cancer mortality rates were higher in rural counties (rural rate 8.6, 95%CI 7.2–10.1) than in metro counties (metro rate 5.9, 95%CI 5.7–6.0; rate ratio 0.81; p<0.001).

See Supplementary material 2 and Supplementary material 3 for age-adjusted incidence and mortality rates, as well as corresponding confidence intervals and tests of significance.

Conclusion

Leading up to 2020, the previously identified rural–urban disparity in HPV-associated cancer was largely due to higher rates in non-metro counties compared with metro counties (with consistent rates within non-metro counties). Then, in 2020, the disruptions to the healthcare system, likely reducing opportunities to screen and diagnose HPV-associated cancers, appeared to reduce HPV-associated cancer incidence across all county groups. In 2021, the rural incidence of HPV-associated cancer exceeded the non-metro urban rate for the first time in at least 20 years. Given the rising trends in rural incidence and mortality, HPV-associated cancer mortality will soon exceed non-metro urban rates. Looking ahead, future researchers should avoid analyzing non-metro counties as a single group when investigating rural–urban disparities in HPV-associated cancer.

HPV-associated cancer can be prevented by a vaccine9. However, HPV vaccination rates are lower in non-metro than metro counties10. Again, however, there is likely variation within non-metro counties. Given low historical adherence to HPV-vaccine schedules and the negative trends in this current study, I predict that the rising rural burden of HPV-associated cancer will intensify in the coming decade without effective prevention and control strategies in rural America.

Funding

This research was supported by the American Lebanese and Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC) of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital.

Conflicts of interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Assistant Professor Jason Semprini, Des Moines University Department of Public Health, West Des Moines, USA