Introduction

Perceived social support is a psychological construct that is used to describe the ‘perception of adequacy’ of the support being provided by a person’s social network1. This construct is subjective (ie personal to the recipient), with meta-analyses showing only a modest association between ‘actual’ received support and the perception thereof2. Higher perceived social support has been linked to multiple health-related, psychological, and other benefits across numerous studies over the past several decades and among multiple populations. At the same time, systematic reviews have indicated that such findings tend to be nuanced (eg as to direct or indirect effects, matching of specific sources of perceived support with specific subpopulations, and many other granular considerations)3-5. During the COVID-19 pandemic, elevated perceptions of social support were associated with increased hope; improved sleep quality; and reduced loneliness, depression, and anxiety6,7.

The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) is a short, simple psychometric instrument originally developed in English that measures perceived social support from three sources: family, friends, and a significant other/special person1. Each of the 12 items in the MSPSS is rated on a seven-point response scale ranging from 1 (‘very strongly disagree’) to 7 (‘very strongly agree’)1. Subsequent studies of the MSPSS have supported its validity and reliability among English-speaking populations8-10. The MSPSS has been widely translated – our best estimate is that the original English instrument has been translated to at least 35 languages. Recent validation studies in other languages include those among Vietnamese people living with HIV/AIDS11, among patients with cancer in Malaysia12, and among pregnant women in rural Pakistan13, among many other examples. However, a 2018 systematic review of 70 articles analyzing the MSPSS in 22 languages found that many such studies relied on a single translation without attempting to understand the meaning and context or to reconcile linguistic and cultural differences14.

In addition, and of particular interest to our study team, the MSPSS has rarely been translated into tribal languages, many of which may be commonly spoken in rural areas (apart from its translation in Chichewa and Chiyao15; Bantu languages that are widely spoken in Malawi; and in parts of Mozambique, Zambia, and Zimbabwe16). Given several authors’ ongoing work with, and/or membership in, Navajo communities in the south-western US, we wanted to have access to a localized translation of the MSPSS. Further, we were interested in ensuring that the instrument and related instructions were not nominally translated, but rather that we fully understood the meaning embedded in the translated MSPSS.

Therefore, we designed a study to:

- coordinate the translation of the MSPSS in Diné bizaad, the language of the Navajo tribal members17, by local community groups

- understand the cultural and language-specific meaning of concepts used in the MSPSS, within the context of the instrument (such as ‘friend’, ‘family’, ‘significant other’, and ‘social support’), by working with Navajo community members in an immersive focus group discussion18.

Methods

Context and reflexivity

The principal investigator (TD) is an assistant professor of public health at a Native American-Serving Nontribal Institution (NASNTI) in south-western Colorado, an undergraduate college with a student body composed of 44% first-generation students and representing 113 tribes and Alaska Native villages19. In her current role, TD has sought to expand the availability of resources for Navajo communities and students20. Her community-based participatory action research (CBPAR) among Global South and underserved Global North populations, and her recent community engagement-focused research, has emphasized the need for, and importance of, socioculturally responsive health communication21-23.

Additional collaborators and co-authors include the original developer of the MSPSS (GZ)1, who mentored TD by sharing stories, experiences, and technical papers from the previous translations with which he had been involved. The second author (JA) was TD’s former doctoral advisor and has a complementary research portfolio that includes qualitative studies with TD21-23 and research into the use of language in reporting research24. Author CK is both a recent alumnus of the college, a member of the Navajo community, and has worked with TD as a student mentee on other academic projects25. Prior to initiation of the study, TD introduced CK to GZ to share about the Navajo culture, and her perspective about this work, and she provided important guidance throughout the work.

Participants and setting

Focus group participants were identified through a mix of snowballing and convenience sampling processes. TD (first author) shared information about this study with the students in global health and public health ethics classes that she taught. As part of the information sharing, she requested students to help by identifying community members who (1) were adults (age ≥18 years), (2) self-identified themselves as Navajos, (3) were fluent in both Navajo (Diné bizaad) and English languages, (4) agreed to meet in a non-reservation area in south-western Colorado, (5) practiced the Navajo culture, and (6) were potentially interested in participating in a focus group to translate the MSPSS scale in Diné bizaad, and to discuss the meaning of MSPSS key terms ‘friend’, ‘family’, ‘significant other, and ‘social support’ in their cultural context.

A few students shared this information with their immediate families and clan-related members, which led to the identification of eight potentially interested community members. TD made phone calls, followed by emails, to further coordinate, communicate, and invite eight self-identified Navajo community members, each of whom fulfilled all six inclusion criteria. All eight community members agreed to participate in the study.

The focus group was held in May 2023, in the house of a community member, who volunteered the space for this purpose. The discussion lasted approximately 2.5 hours. The participants were four male and four female Navajo adults, with an age range of 30–60 years. Each participant was given a print copy of the MSPSS in English, and the study rationale was explained to them. Following review of the study information, each participant provided written informed consent in accordance with institutional review board requirements.

The focus group began with each participant introducing themselves in a manner commonly used in Navajo culture, by highlighting their paternal and maternal clans, rather than their titles or educational backgrounds. The discussion of MSPSS key terms was facilitated by TD and CK. CK’s familiarity with the group, and her ability to synchronously translate the group discussions from Diné bizaad to English, were helpful in achieving the study goals. A brief semi-structured guide with the following open-ended questions was used to support the discussion:

- In your culture, what is the concept of a 'friend'? Please describe.

- Please describe 'family'.

- What is the meaning of 'significant other' in your culture? Please describe.

- Do you think these terms (‘friend’, ‘family’, ‘significant other’) have changed over time? Can you give some examples?

- Do you think that the concept of ‘social support’ has changed/evolved during the pandemic? Can you give some examples to explain this?

Data analysis

The discussion was audio-recorded, and thereafter transcribed verbatim by CK during June and July 2023. At this stage, the transcription was also anonymized. The transcription was read and reread both by TD and CK to check for typographical errors or other inadvertent mistakes. All repetitions, and words or phrases that did not add any extra meaning (eg pause words), were removed at this stage. Thereafter, in August 2023, the transcription (which was initially a bilingual verbatim transcription) was fully translated into English by CK, then backward–forward translated and checked for accuracy by a local Navajo teacher. In member-checking meetings, both the bilingual and English versions of the focus group transcripts were checked by the discussion participants to confirm that the original meaning had not been altered.

All analyses of the transcript used inductive coding26 and were completed using NVivo 21 (Lumivero; https://lumivero.com/products/nvivo). First, the transcription was coded separately by authors TD and CK. Thereafter, they iteratively discussed their categorizations six times during October and November 2023 until they had achieved 100% consensus as to the codes and assignments.

Integrating community-based participatory research

TD’s existing social and research connections with Navajo community members, and CK’s membership in the same community, enabled meaningful collaboration between ‘thought partners’ (typically referred to as stakeholders in the western context of projects/programs) during the study. For example, each focus group discussant was given ‘gratitude gifts’ (such as gardening tools and vegetable seeds), which are somewhat atypical incentives (as opposed to gift cards or similar items), but members of the community indicated that these items would be the most useful and functional for them. As previously described (in ‘Participants and setting’), the meeting time and space for the focus group was based on community members’ preferences and convenience (a participant’s home). These steps reflect the adaptability to community members’ preferences and needs that is often present in sustained community partnerships27. Similarly, the focus group participants spent the first 15–20 minutes silently reading and contemplating the English MSPSS tool before the discussion began, in alignment with their expressed preferences for learning and understanding28.

We infer that these efforts to design research methods in true partnership with the community were successful given ad-hoc statements made by participants indicating a sense of pride and ownership of the work. For instance, one participant said, ‘As a Navajo myself, it will be my pride to be a part of this research from its initial stages and contribute building empowered research relationships between communities and the college’ (Female, age 30).

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Fort Lewis College in April 2023, IRB-2023-86.

Results

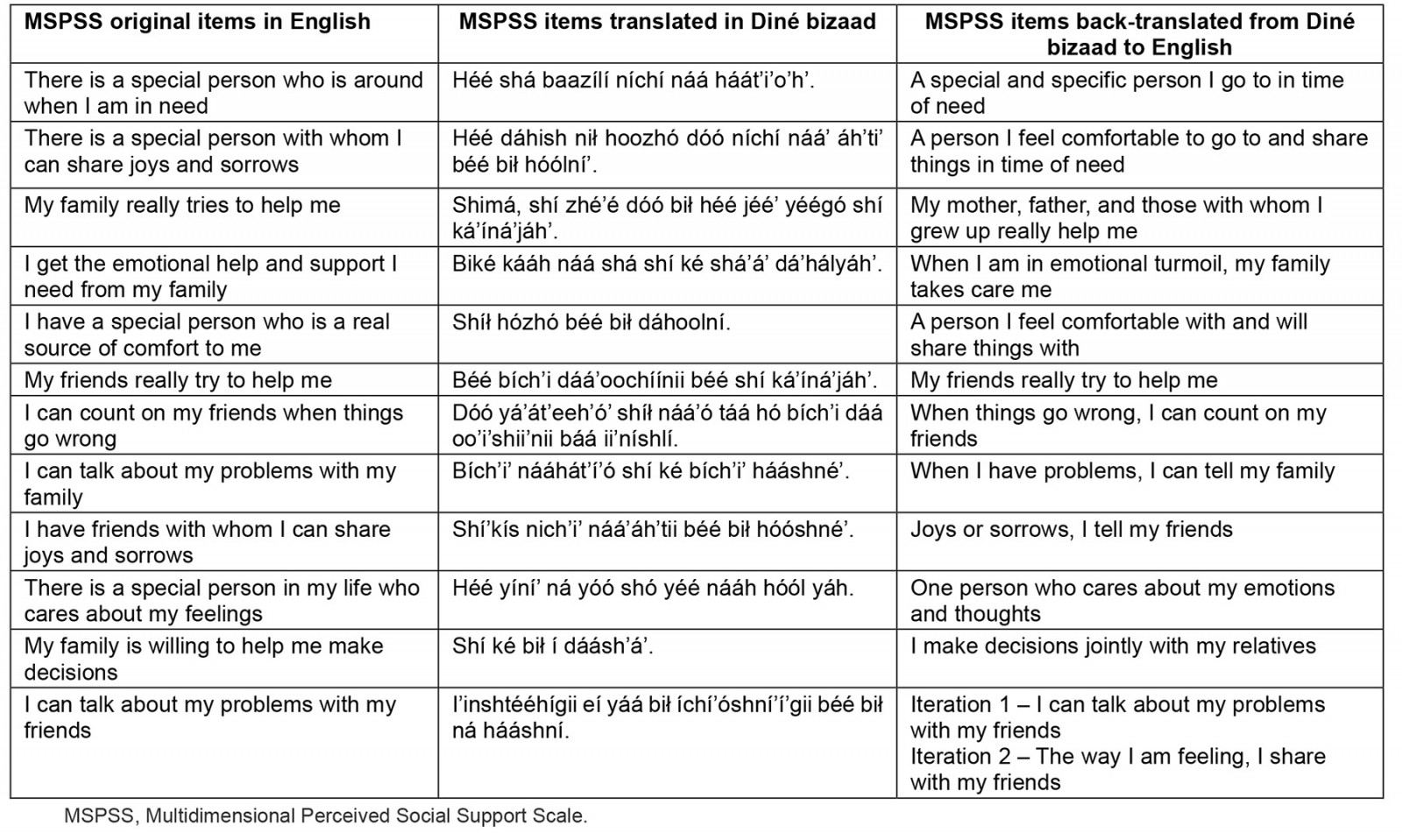

The iterative process of translation, back-translation, focus group discussion, and member checking in Diné and English led to a harmonized Navajo MSPSS instrument (Table 1). As expected, and as described throughout these results, multiple core concepts and words from the MSPSS were not overtly stable between cultures and had to be unpacked. However, discussants were from the same community, so there was a degree of homogeneity, which likely facilitated understanding of cultural terms and meanings of the words. The translated tool reflects the group’s approach to interpretation, language usage, and conceptual equivalence, rather than any individual’s determination of the meaning of MSPSS terms.

In some cases, when items were linguistically or culturally elusive, the community members developed consensus about the most appropriate translation following detailed discussion. For example, for the item, ‘There is a special person who is around when I am in need’, discussions deconstructed the meaning of ‘around’ as ‘having someone who is physically close by’ or ‘is omnipresent in the mind even though physically not staying close by/together’. Similarly, for the same item, there was deliberation around whether ‘need’ is a ‘precursor of receiving any social support’, or whether social support would be there ‘irrespective of any explicit need’.

Table 1: Translation and back-translation of Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support items

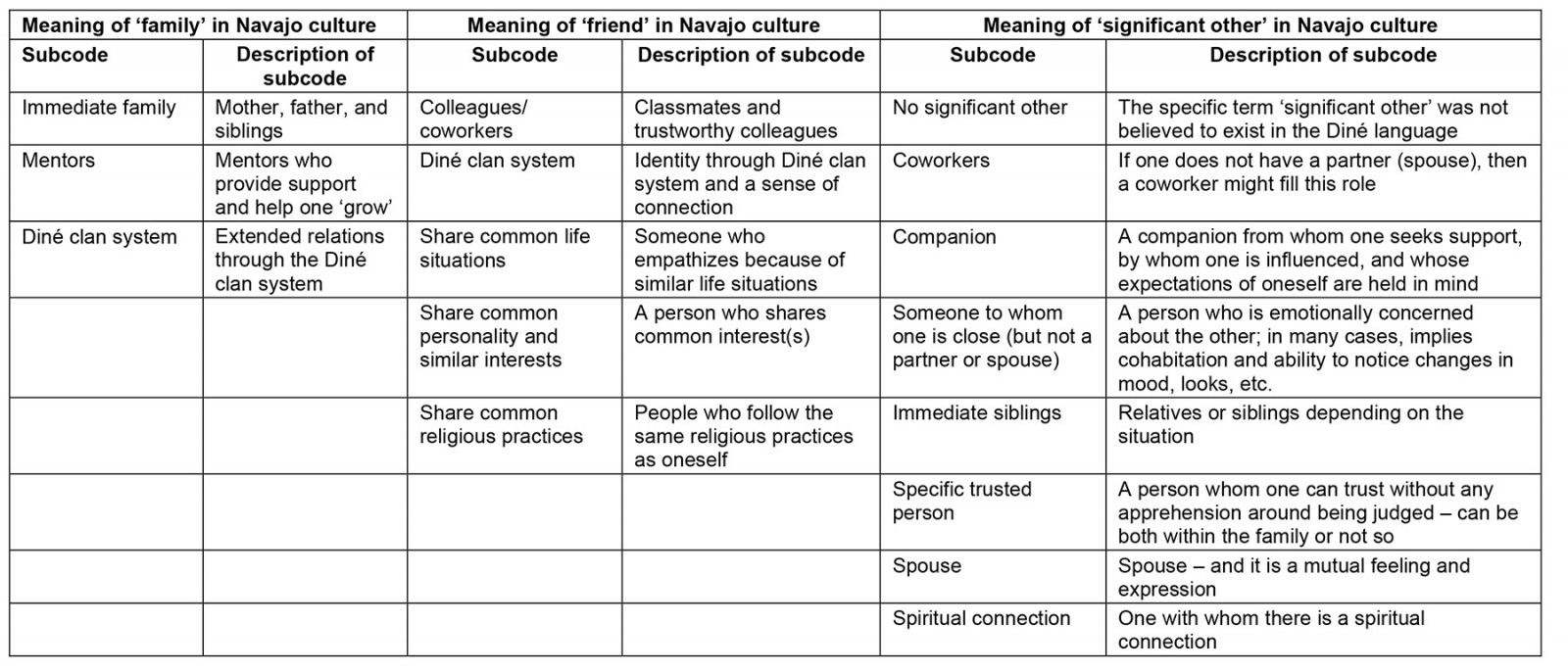

Friend, family, and significant other

Table 2 summarizes the conceptualizations of ‘friend’, ‘family’, and ‘significant other’ by the focus group participants. The concept of ‘family’ was characterized broadly by ethnic clan-based close-knit bonds that included ‘immediate family members’ such as parents, siblings, and nieces; ‘extended family in the Diné clan system’; and mentors, ‘people who would support, and guide you along the way to help you grow as a person’.

The concept of ‘friends’ was also extensive and included ‘colleagues’ and ‘coworker[s] who were from the same clan’ or ‘were living/growing up in the same place’. One participant mentioned:

So, when we say friends, the first thing you tell each other is your clan. For example, I started working at the health center and the first thing I would say to my coworker is my clan, where are you coming from – your roots? [Female, age 52]

Other participants described people with whom one shared a sense of bonding and connection because of certain similar life situations and/ choices. For example:

… the person who has same situation and can relate to and understand each other. [Female, age 55]

I like to go hiking and like people who are adventurous. That's social support too … talking to people where there's some match. [Male, age 55]

Finally, some of the group members also believed that people following the same faith or ‘religious practices’ would be considered friends.

The meaning of ‘significant other’ had the widest range of interpretations. For many participants, it referred to an ‘immediate family member’, a ‘spouse’, or ‘coworkers, in the absence of a spouse’. Some participants also included other family members (eg both ‘… husband and sisters’). For unpartnered participants, ‘significant other’ constituted ‘someone they trust’ and ‘can tell whatever is there in their mind’.

Interestingly, older participants indicated some filtering while sharing with their ‘significant other’. One participant mentioned, ‘You tell them certain things, and will not tell them certain things’. Some of the older respondents also had a unique viewpoint and mentioned that there was ‘… no significant other term in the Navajo culture’, and it is only the deep connection with ‘the divine’ and ‘a spiritual connection’ that is considered as ‘significant other’. For some participants, this included acknowledging relationships with ‘nature’, ‘animals’, ‘ceremonies’, and ‘medicine men’ as deep, intergenerational, and traditional, that provided healing but that also served as ‘social support’.

Table 2: Summary of participants’ interpretation of key terms from the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support in Navajo culture

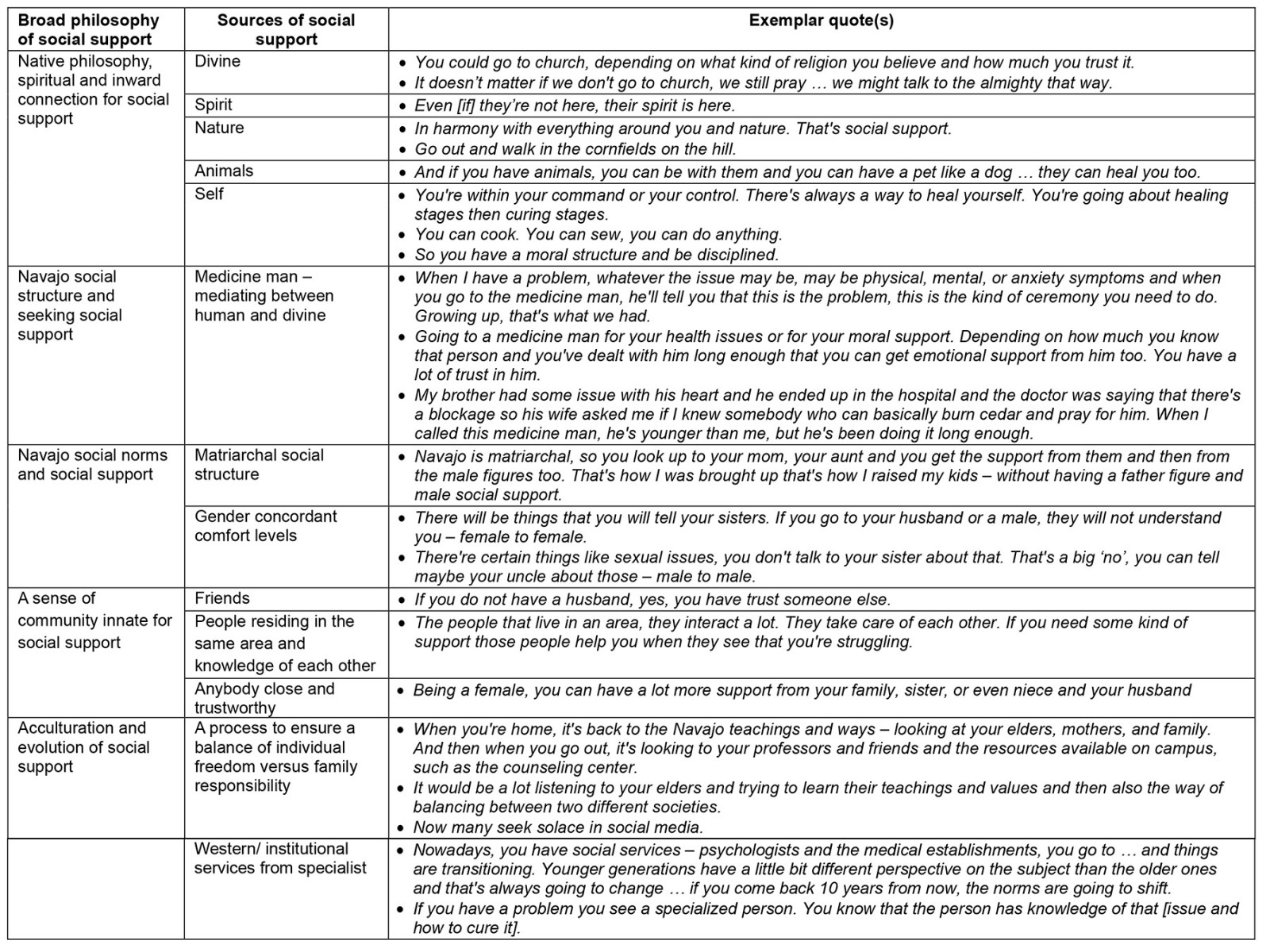

Social support

The conceptualization of ‘perceived social support’ was multifaceted, and discussants described five categorical philosophies of social support, each entailing multiple sources (see Table 3 for a full description of each category and exemplar quotes). These included caring support from communities, emotional support from friends and family members, developmental and informative support from mentors, professors, or trained specialists such as counselors, and help received from community members.

‘Perceived social support’ was highlighted as a trust-based rather than need-based omnipresent feeling by all the discussants. Partners (spouses) and family members seemed to offer the greatest hope of support when someone had a chronic health issue (eg cancer, alcohol use disorder). However, there appeared to be individualistic and age-based differences. For example, one younger male participant perceived the greatest social support from his friends, and another younger female participant perceived the most social support from her professors and campus services. Older participants also mentioned, and appeared to specifically disfavor, changing patterns of social support among ‘youngsters’ who would seek support from social media.

Gender-concordant bonding came across as a key route for trustworthy relationships among community members, wherein female members would uninhibitedly share and seek support from their grandmothers, mothers, aunts, sisters and half-sisters, and nieces, whereas men expressed similar aspects with their uncles, fathers, stepfathers, and cousins. Male-to-male and female-to-female sharing and support seeking were particularly indicated in the context of private or confidential sex-related inquiries.

While trust came across as an innate factor of perceived social support, need-based social support from traditional sources like medicine men (eg providing guidance for ceremonies) was also mentioned. Some participants described popular Native activities such as sewing, beading, and cooking to ‘be disciplined’ and as a way of seeking solace through oneself. Several discussants described going to church, hiking, mingling with nature, and spending time with animals as sources of healing, that were also broadly conceptualized as ‘social support’. One discussant who had never been married expressed ‘keeping things to themselves and not seeking social support’ to avoid passing on stress to others.

Table 3: Navajo philosophies and perceived sources of social support, with exemplar quotes

Discussion

This article reports the processes and outcome of our work translating the English MSPSS into Diné bizaad using principles from CBPR, such as engaging the community throughout the research process and working toward consensus building among Navajo community members28. This process appropriately precedes formal analyses for internal reliability and construct validity given the differences in meaning that exist for multiple words and phrases in the instrument and its constituent items across cultures. Indeed, the absence of this process from many MSPSS translation efforts was noted by a systematic review14.

Using methods from CBPR and drawing on guidelines and suggestions by Indigenous researchers29, community members co-translated the MSPSS, while explaining the social constructs around the MSPSS key terms ‘family’, friends’, ‘significant other’, and ‘perceived social support’. The goal is for the reconciled, translated MSPSS to remain as close as possible to vernacular, be easily understood by a layperson (eg who might be responding to the instrument), and to potentially have higher odds of being adapted by the Navajo community members.

At the same time, our process itself is not unique, and has been used to adapt other validated screening tools. For example, a pair of researchers translated the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 from English into Dinka, a South Sudanese tribal language, following a similar collaborative translation process30. In doing so, the authors noted that this process is an essential first step in adapting such tools among different sociocultural groups30. Other scholars have argued for the value of ‘linguistically and culturally appropriate’ language, particularly when attempting to communicate about health issues31, such as during the COVID-19 pandemic32.

Subjectively, it is our impression that conducting this form of community-engaged work benefited from pre-existing rapport and trustworthy relationships between TD (as the study principal investigator) and co-authors and community members, including collaborative translation of COVID-19 information during the first years of the pandemic33,34. Similarly, TD’s notes on perceived reflexivity (‘journaling’) during the study seemed to facilitate rich and honest discussions of semantics and cultural norms35. These experiences, in combination with a co-author and collaborator who is a member of the Navajo community (CK), helped ensure community-driven interpretation of the core ideas in the MSPSS, rather than top-down assertion of the English-language meaning36.

Throughout the Diné bizaad translation process, Navajo values of appreciation for the land, nature, family, and clan37 were evident in how terms were understood. Spirituality was perceived as part of social support by some participants and was associated with healing, particularly when related to psychoactive substance use38. The varied meanings of ‘friend’ and ‘significant other’ in Diné were broad and often associated with perceived trustworthiness. Studies of the MSPSS in other cultures have sometimes identified similar nuances through analyses. For example, the Chinese MSPSS translation for high school students found a single factor for ‘friends’ and ‘significant other’ rather than separate factors39. Some cultural translations have found that all three components (friends, family members, and significant others) were aligned with a single-factor solution, as among antenatal women in Pakistan40. At the same time, translations to some other languages, such as Thai, have found that the questionnaire retained a three-factor solution41. However, the Thai translation may have retained the three-factor structure due, in part, to the authors’ addition of the following instruction: ‘Note: special person excludes friends and family’, highlighting a priori the fact that some respondents and some cultures may perceive overlap between the dimensions.

Limitations

This study resulted in a version of the MSPSS instrument translated into Diné bizaad language via a harmonized translation, back-translation, discussion, and member-checking process. It also produced information reflecting perceptions of the meaning of key MSPSS terms among Navajo community members residing in the south-western Colorado area. Given the nuances of the language, findings may not be fully generalizable to Navajo communities who live in other parts of the US, who might have different accents, descriptions of terminology, or sociocultural beliefs. In addition, this study was a precursor to, but not a replacement for, quantitative assessment for validity and reliability among those who use the Diné bizaad language.

Conclusion

This article provides an example of how researchers and community members can work side by side toward a common goal, in this case the translation of the MSPSS to facilitate higher quality health and wellbeing assessments in the US Navajo community. With this translation – and assessment of the meaning of key terminology – in hand, subsequent research focused on validity and reliability of the instrument using typical quantitative approaches (eg factor analysis) will be a useful next step. During that process, it may also be instructive to compare the validity of this community-translated version of the MSPSS to an alternative, direct translation of the MSPSS to Diné bizaad that does not adjust for community input about the meaning of words and terms. It may also be useful to conduct a quantitative validation study in multiple different Navajo communities to explore the degree to which local nuances in language affect responses to questionnaire items.

Acknowledgements

Portions of this research and study, including some verbatim text, were presented at the 2024 American Public Health Association Meeting in Minneapolis, Minnesota, as part of an abstract and poster session (abstract #550487).

We are particularly appreciative of the support provided by the focus group discussion participants and by Clara Francis, a former Diné language teacher, who provided verification services.

Funding

This project was made possible through research funding support from author GZ in addition to supplemental funding that facilitated the completion of this work from the Intuitive Foundation, Fort Lewis College Pay-It-Forward Grant, and the Fort Lewis College Summer Mini Grant program.

Author CK was a student when the research was conducted, and was mentored on research methods utilizing the Pay it Forward Grant (an undergraduate research grant by the college that provides stipends to students and smaller stipends to their respective faculty mentors to collaborate on a community and/or global health research).

Conflicts of interest

Unrelated to this research, GZ has served as an external advisory board member for Merck, Pfizer, and Moderna and as a consultant to Merck; has received investigator-initiated research funding from Merck administered through Indiana University; and serves as an unpaid member of the Board of Directors for the Unity Consortium, a non-profit organization that supports adolescent health through vaccination. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest related to this work.

References

You might also be interested in:

2011 - Colorectal cancer screening among rural Appalachian residents with multiple morbidities

2008 - Correction, article no. 824: Attracting psychiatrists to a rural area - 10 years on