Introduction

The small size of Malta has contributed to an almost indiscernible rural–urban difference1,2. Most urban areas join each other, particularly in the central and southern regions1. There is no consistent definition of urban areas. To surmount the issue of urban–rural indiscernibility, it seemed best to rely on categorisation made by local experts. Valletta, the capital city of Malta, has the most dense population on the island, with high crime rates and special health problems. This is due to the ship-repairing and ship-building industry, and traffic density. The cities surrounding the harbour area represent the urban region3. The north of Malta is characterised by a more suburban background where agriculture is a popular part-time activity1.

Several methodological and conceptual problems arise when discussing rural–urban health inequities in small islands1,4. It is thought that social homogeneity reduces the tendency for health and social disparities in a discrete geographically defined population as in island communities1,5. The greatest challenge in a small island with a high population density might be finding, measuring and presenting health discrepancies. Consequently, before presenting statistical evidence, it is important to outline the modus operandi of the local primary healthcare system1.

In Malta, primary health care is provided by two parallel interacting but independent systems. There is a state primary care (PC) service and a private general practitioner (GP) service with no official patient registration system. GPs from both sectors can refer patients for radiography in public healthcare centres. The public system is free of charge at the point of use. These salaried public GPs are available 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Private GPs work in their own offices or within community retail pharmacies. They charge relatively modest, often out-of-pocket, fees sometimes refundable through private health insurance schemes6. The private sector provides better relational and longitudinal continuity of care whilst the public sector offers better access to out-of-hours care7.

Demographic changes, growing demands and expectations, technological developments and rising healthcare costs will strongly challenge European health systems in the coming decades. Countries are looking for solutions to tackle these problems8. Maintaining high-quality PC to achieve more cost-effective and better-coordinated care is one of the local reform challenges.

Strengthening PC presupposes accurate data about its current form, informing policymakers on the potential avenues for further policy development and deployment. However, data on PC provision in rural and suburban areas are lacking. Further research is required to examine the ways in which PC provision can be improved in such areas9,10. The aim of this study was to examine the urban–suburban differences in the indications for lumbosacral spine radiographs in a public primary healthcare centre in Malta.

Methods

The target population were all patients who underwent lumbosacral spine radiography in a public primary healthcare centre between January and June 2014. Exclusion criteria included undergoing lumbosacral spine radiography in the public hospital and those radiographs covered by out-of-pocket expenses. The GPs’ requests for lumbosacral spine radiographs were classified according to the evidence-based indications posited by the American College of Radiology, the American Society of Spine Radiology, the Society for Pediatric Radiology and the Society of Skeletal Radiology in 201411.

Personal data such as names, identification numbers and contact telephone numbers were not recorded. Patients’ places of residence were noted. The urban cities and suburban villages were defined as considered in the European Urban Health Indicator System project relying on the categorisation made by local experts3. The cities surrounding Valletta and the harbour area represented the urban region. The data were manually retrieved from the Radiology Information System and Picture Archiving and Communication System and it was entered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. This data was anonymised and stored accordingly.

Analysis of the data was subsequently carried out using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences v20 (SPSS; http://www.spss.com). Differences between suburban and urban areas were analysed using the χ² test. Direct logistic regression was used to estimate the influences of different patient characteristics and imaging indications in urban and suburban areas.

Ethics approval

Permission was sought from the Data Protection Officer of the Primary Health Care Department and Mater Dei Hospital, and from the Clinical Chairperson of the Radiology Department. The study received ethics approval from the University of Malta Research Ethics Committee on 26 June 2015 (reference number 22/2015).

Results

The majority of the participants were females (55%, n=605). Around three-quarters of patients (78%, n=861) resided in suburban regions and 22% (n=241) in urban areas. The sample population had an age distribution of 8–96 years with a mean of 55±17 years. Public GPs referred 74% of cases (n=845) whilst 23% (n=255) of patients had attended their private GP.

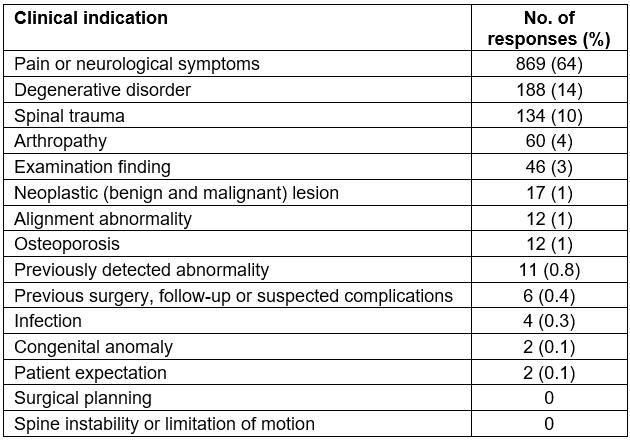

Major indications for lumbosacral radiographs included lower back pain or neurological symptoms (64%), degenerative disorders (14%) and trauma (10%) (Table 1). Doctors’ requests for lumbosacral spine radiography in suburban patients were more likely to be submitted from the private sector. The GP in the urban clinics tended to include more examination findings in the request form.

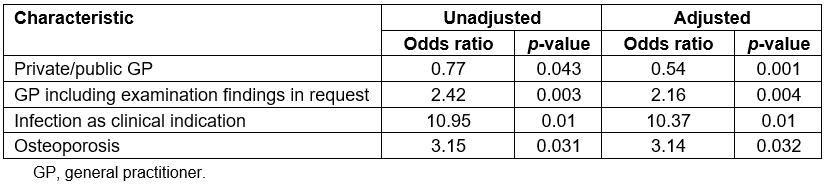

The logistic regression model predicting the likelihood of different factors occurring withsuburban patients as opposed to those residing in urban areas contained four independent variables (private/public sector, examination findings, osteoporosis, infection). The full model containing all predictors was statistically significant, c2 (4, N=1112) = 26.57, p≤0.001, indicating that the model was able to distinguish between patients residing in urban and suburban areas.

The model as a whole explained between 2.4% (Cox and Snell R2) and 3.6% (Nagelkerke R2) of the variance in suburban/urban areas, and correctly classified 78.5% of cases. As shown in Table 2, all four of the independent variables made a unique, statistically significant contribution to the model. GP requests for lumbosacral spine radiography in suburban patients were more likely to be submitted from the private sector whereas urban GPs tended to include more examination findings. Lumbosacral spine X-ray requests due to infections and osteoporosis tended to be more prevalent in urban patients.

Table 1: Clinical indications for requesting lumbosacral radiographs

Table 2: Logistic regression predicting likelihood of different factors occurring in patients residing in suburban areas as opposed to urban areas

Discussion

Consistent with other studies, the majority of patients were females7,12-14. The patients’ average age in this study was similar to that reported in a US-based study carried out in a level II emergency department (55 years vs 56 years). However, the age range of the current study was larger (8–96 years vs 17–98 years).

Although the private sector accounts for 70% of primary healthcare contacts, the ratio of public to private GP referrals for lumbosacral spine radiographs was 3:16. Moreover, the urban GP tended to include the examination findings in the request form. This reflects the difference in how the suburban GP and the urban GP work as they are responding to structural conditions. PC services could be responding to urban and suburban residents in sync with their demands. Further research can target this.

Qualitative systematic review and meta-synthesis postulated that rural communities supported long-term mutual relationships and feelings of a sense of belonging15,16. GP requests for lumbosacral spine radiography in suburban patients were more likely to be submitted from the private sector. This might be because of wealth or because suburban patients might value more relational continuity of care7. Lumbosacral spine radiography requests due to infections and osteoporosis tended to be more common in the urbanised setting. This could be related to the high density of people. This showed that one can find and measure health differences in a small island1. This significant finding of this study reflects the two distinct populations being served by the public and the private sectors. Future studies can address these research questions.

Potential limitations were identified in this study. Due to time and resource constraints, lumbosacral spine radiographs carried out in private PC clinics were excluded from this study. This study did not assess whether such requests are grounded in evidence-based medicine. Future research can address these limitations to strengthen the PC system.

Conclusion

This study showed that there are health differences between the urban and suburban communities. This reflected the difference in how the suburban GP and the urban GP work as they are responding to structural conditions. These findings provide valuable information to PC clinicians, policymakers and researchers to improve resource allocation and improve patient outcomes.