Introduction

Snakebite envenomation has been described by the WHO as a neglected and poorly treated tropical disease. It is a public health problem in tropical and subtropical regions, including Latin America, where a lack of uniformity in preclinical and clinical approach has been reported1,2. An estimated 51 995 snakebites take place in the Americas yearly, while 337 deaths due to snakebites are reported each year2. Snakebites are commonly treated in first-contact health facilities, as they usually occur in remote areas, where resources and personnel can be insufficient, while transportation to urban hospital can cause a delay in treatment3,4.

In cases of snake envenomation, treatment during the first 2 hours of the event is crucial to a patient’s prognosis5. In Mexico at least, it is still unknown if the selection and administration of antivenoms are adequate to reduce mortality. Several snakes are endemic to Central American rainforests, including Bothrops asper. B. asper is a viper that affects tissues by causing myonecrosis, dermonecrosis, hemorrhage and edema. A delay in serotherapy can reduce the effectivity of antivenoms6. The objective of the present communication is to describe and analyze the case of a snake envenomation (Bohtrops asper was suspected) in a patient from an urban, agricultural region, which represents the coexistence of predominant barriers for providing timely and effective treatment for the envenomation and its proximate consequences. The geographical, environmental, cultural, socioeconomic and healthcare-access context of this patient is shared by many individuals living in agricultural or sylvatic areas of Latin America. Thus, this case report represents a common health problem that might be of interest for health professionals throughout this region.

Case report

The patient was a 40-year-old male man, a Mayan-ethnicity farmer who lived in a rural community in south-eastern Mexico. In this region there is a wide distribution of B. asper. On the day of the incident the patient left his home to arrive at his farm early in the morning; whilst working he was bitten by a snake on the dorsal popliteal fossa of his left leg. Following the bite the patient fell, causing head trauma.

At midday, the patient was found semi-conscious by his family, and transported to the local general hospital. During transportation a tourniquet was placed on the left leg and his head covered with non-compressive cloth bands by paramedics.

At the medical examination at the general hospital, 5 hours after the accident, multiple, diffuse ecchymoses were identified on his body. Leg tourniquet and head bandages were removed during examination and placed back soon after the personnel identified active bleeding in both areas. The patient had tachycardia and blood pressure of 100/50. The results of laboratory tests were suggestive of renal failure indicated by abnormal elevation of ureic nitrogen, hypokalemia and hyperglycemia, in addition to hyperbilirubinemia, thrombocytopenia, leukocytosis and retardation of coagulation (Table 1). Bothrops asper (locally known as Nauyaca) was the suspected species. A total of 15 vials of antivenom serum were administered in 1000cc solution, in addition to intravenous application of steroids and antibiotics. Subsequently, the patient was transferred to a second-level hospital, located 100 km from the site of the incident, he arrived at a second-level hospital, 8 hours after the snakebite; his diagnosis was snake envenomation corresponding to Christopher-Rodning IV, multiple organ failure, compartmental syndrome in the left leg, severe digestive tract bleeding and cranioencephalic trauma.

On the patient’s arrival to the general hospital, he was taken to the emergency room and treated with vasoconstrictors, sedation, mechanic ventilatory assistance and endovenous solutions. The patient remained anuric with elevated blood nitrogen, high serum levels of muscle enzymes and hyperchloremia. Coagulation tests confirmed the inability to coagulate. He developed massive edema in the affected leg, and a fasciotomy was carried out. On the same day, intensive therapy was initiated with the diagnosis of disseminated intravascular coagulation and amine-dependent distributive shock. There is no record of re-evaluation for anaphylactic reactions after initial antivenom administration, nor any record of further antivenom serum administration.

On the second day of hospitalization, cranial lesions were identified in a tomographic scan. Hemodialysis treatment was initiated to treat acute renal failure (AKIN II). The patient was transfused with platelet concentrates to mitigate the persistent active bleeding. On the third day, the patient died, and the death certificate stated that the cause of death was the snake bite, hypovolemic and distributive shock along with acute renal failure.

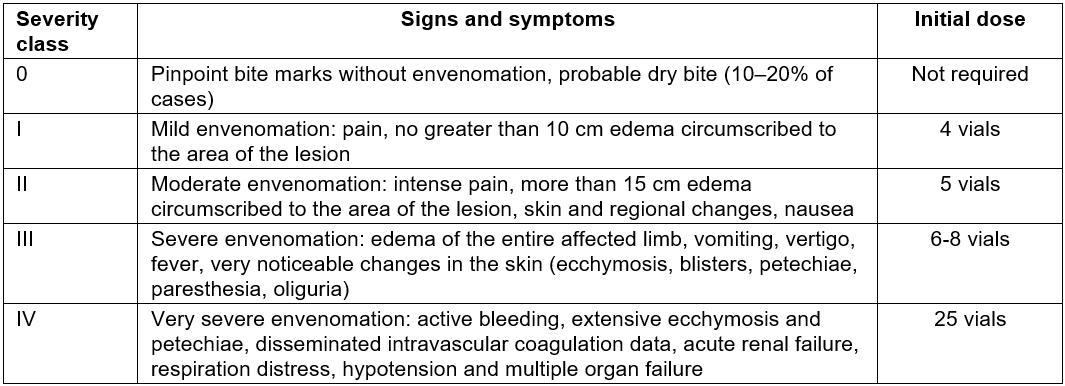

Table 1: Christopher-Rodning classification of the signs, symptoms and initial treatment with antivenom for snakebite envenomation of the family Viperidae

Ethics approval

A relative of the patient provided written consent (approval number CE0162017).

Discussion

We have presented the case of a patient that experienced a snakebite, an envenomation accident, followed by cranioencephalic trauma whilst being geographically and socially isolated. The isolation and lack of timely treatment at the local hospital delayed the initiation of medical attention.

Many aspects of this case can be analysed to improve knowledge and enhance the medical attention given to future patients in similar conditions of social and geographical isolation, considering that the clinical evolution of the patient was congruent with that previously described in existing literature5,6. However, rural medical personnel face a lack of resources and training, and thus procedures are not always adhered to follow the National Clinical Practice Guidelines to treat envenomation5.

The time that elapsed between the bite and the initial treatment might have contributed to the patient’s fatal outcome. The priorities for the initial approach of the envenomation treatment for a patient bitten by a viper include the prompt medical attention, because the prognosis for envenomation is directly related to a timely diagnosis and treatment4. However, the transport is difficult in rural agricultural sectors of south-eastern Mexico, as in many other rural areas of Latin America.

The use of tourniquets is contraindicated because they result in higher morbidity by facilitating necrosis and fibrinolysis of the peripheral nervous system and when removed can provoke massive envenomation. In the present case it was known that the patient arrived with a tourniquet on the affected limb. It is therefore important to acknowledge that if a tourniquet or compression bandage has been fitted, it should be left in place and only be removed after antivenom infusion has commenced5. The administration of antivenom is based on the Christopher-Rodning envenomation criteria (Table 1). Prior to the persistence or aggravation of the clinical manifestations, the antivenom should be administered at an initial therapeutic dose every 4 hours4,5. In the present case, the antivenom was applied as a single dose, because the administration of the total 15-vial dose was suspended during the patient’s transfer instead of re-evaluating the conditions of the patient after administration.

In accordance with Christopher-Rodning IV criteria, the indicated therapeutic dose for envenomation grade IV is 25 or more, instead of the 15 vials that the patient received. Some protocols still dictate that corticosteroids be administrated in conjunction with the antivenom for specific cases, but these are generally found as contraindications because they affect coagulation and their use could aggravate underlying conditions. The administration of several medicines with the antidote overwhelms metabolic capacity, which is already diminished by the cellular destruction that the venom causes1,3.

Fasciotomy is indicated in patients that have evidence of high compartmental pressure and also in those who have capacity for homeostasis. When patients have impaired coagulation ability it favours haemorrhage, loss of systemic arterial pressure and, eventually, distributive shock or hypovolemia. Some authors recommend fasciotomy in all cases of envenomation due to snake bite, but in the present case the hemodynamic stabilization in the patient could have been achieved before the fasciotomy and not after the procedure7,8.

An alternative treatment to compartmental syndrome is the use of hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Although its specific use in ophidian envenomation is still experimental, the Hyperbaric Medicine Society approves its use for different types of envenomation as well as for compartmental syndrome and necrotizing fasciitis. Early use of hyperbaric oxygenation reduces the risk of necrosis and secondary cellular ischemia; before the risk assessment it should have been considered as an alternative that does not implicate incisions nor bleeding9-11.

We emphasize the importance of primary prevention and health promotion that can favour the management and adequate transfer of patients at high risk of snakebite envenomation, as well as ongoing training of health personnel and the updating and contextualization of clinical practice guidelines, to the resources that are available in rural areas. Specific guidelines for improving the initial management and transfer of patients from isolated areas should be implemented, but also taught to the first-contact health personnel to promote evidence-based clinical practice12,13.

Conclusion

To reduce fatalities from snakebite envenomation, such as in the case presented here, there is a need for a coordinated multilevel approach of proximate and distant barriers, such as the correct registration of cases, the anticipation of higher risk seasons, collaborative work and continual medical training.