Introduction

Health is an indispensable requirement for the promotion of human development. It is an important symbol and measurement of a nation’s prosperity and strength. Since 1948, after the official establishment of the World Health Organization, health has become a core concept and important social goal that is recognized worldwide. The Alma-Ata Declaration in 1978 once again put forward the global strategic goal of ‘protect and promote health for all’ and ‘everyone enjoys primary health care in 2000’1. Health, as a fundamental human right, and its fairness and equality have gradually been reiterated and emphasized around the world.

Since the founding of China, the protection of people’s health has always been an issue that the central government pays close attention to. The Leaders and the National Health Congress in China have been emphasizing that, without the health of the entire people, there is no well-off society for all, and ‘accessibility’ and ‘equality’ are vital principles in the development and promotion of China’s medical and health services.

Maldistribution of health workforce is a focus worldwide, because workforce quantity and equality will influence the effectiveness, accessibility and sustainability of health services and the medical system, especially for low- and middle-income countries, whose health resources are limited. In China, the disparities in health workforce have been reflected mainly in two aspects: between urban and rural areas, and between different regions. Regions with a better socioeconomic environment and career prospects attract more health workers2. For rural areas, recruitment and retention of health workforce are the main barriers3. After graduation, more medical students would like to work in urban areas, for there are more big hospitals, which have higher salary, more opportunities to learn the advanced technologies and for career promotion. They also choose urban areas for their children, so their children can have better education and living conditions.

In March 2009, the new healthcare reform launched to provide the whole nation with basic medical and health services and ensure that everyone enjoys equal access to basic medical services and primary health care, paying more attention to the strengthening of rural medical and health services and human resources4. Since then, the Chinese government has issued many policies and interventions to cultivate the health workforce to the grassroots health institutions, aiming at improving the supply of health service in rural areas. To strengthen the primary health service and relieve the current shortage of village physicians, the government has introduced and strengthened the general practitioners (GPs) system since 2011, which cultivated the GPs for rural areas and communities so that, by 2016, a total of 209 000 GPs had been trained and qualified, 1.5 GPs per 10 000 people5.

Despite the increase of GPs in China, the total number of village physicians (village doctors and assistants) decreased, and could not be covered by the GPs in short term. From the medical reform in 2009, to 2011, the number of village physicians increased from 1 050 991 to 1 126 443, and then began to decline. By 2016, the number of village physicians had reduced to 1 000 324. The distribution of village physicians is the key to optimize health service supply in rural China under such a circumstance. Equitable health workforce distribution could make full use of current limited village physicians and supply health services for rural residents. But in China, few research studies are concerned with the health workforce distribution in rural areas and the disparities between the rural areas of different regions. It’s well known that the eastern division of China achieved better development after the government’s policy and because of the geographical location. If regions with a better socioeconomic environment and career prospects attract more health workers, then it can be hypothesized that the rural areas in the eastern division of China would get more village doctors and higher equality than other regions of China. This study compared and discussed village physician distribution in China, which can be divided into four regions by economic level and geographic position. The aim was to compare equality in village physicians in these different regions and discuss the practicable suggestions for optimization of the primary health workforce system in China.

Methods

Setting

China is the largest developing country, with a per capita disposable income per rural household of ¥12 363 in 2016. The population in China in 2016 was 1 382 710 000, with 589 730 000 of those living rurally. China has 34 provinces, autonomous regions and municipalities, 31 of them on the mainland. This study aimed to measure the inequality in health workforce of mainland rural areas. Rural areas are also known as villages in China; here, a rural area or village is considered as a geographic area located outside urban areas and townships. Urban areas are residential communities, run by residents’ committees (part of the Chinese administrative hierarchy in cities) and other areas related to construction of the city and their districts, and municipalities and their districts; townships and towns are smaller administrative divisions. The independent industrial and mining areas, development zones, and other special areas with a resident population of less than 3000 people, as well as farm and forest farm, are regarded as villages6.

Given the economic level and geographic position, the 31 provinces, autonomous regions and municipalities were divided into four divisions7, which were the eastern division (Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian, Shandong, Guangdong, Hainan), central division (Shanxi, Anhui, Jiangxi, Henan, Hubei, Hunan), northeastern division (Liaoning, Jilin, Heilongjiang) and western division (Inner Mongolia, Guangxi, Chongqing, Sichuan, Guizhou, Yunnan, Tibet, Shannxi, Gansu, Qinghai, Ningxia, Xinjiang).

Village physicians include village doctors and assistants, who pass a licensing examination and are registered in the health workers information system for the census. In this study, only those whose main employment was recorded as ‘practice’ in ‘village clinics’ were recognized as village physicians. The village clinic refers to the health institution or station established in the village after the examination and approval of the establishment of the county health administrative departments and the practice registration, which has obtained the ‘medical institution practice license’ according to law8. The village clinic is an important part of the rural public service system and the basis of the rural medical and health service system. In short, all village physicians, either licensed doctors or licensed assistant doctors, were included in this study.

Data

The main data sources for this analysis were collected from the China Statistical Yearbook 2010–20179. National Bureau of Statistics recorded the health data on the number of all health workers, health institutions, health expenditures and financial investment. The village doctor and assistants, which were the basic elements of the health workforce in village clinics, were chosen to assess the inequality of the health workforce in rural China. Because the Chinese government continuously furthered the health reform and the optimization of health resource distribution at a grassroots level in recent years, the data of Chinese village physicians for 2009–2016 was used to assess the inequality in rural health workforce distribution.

Measures of inequality

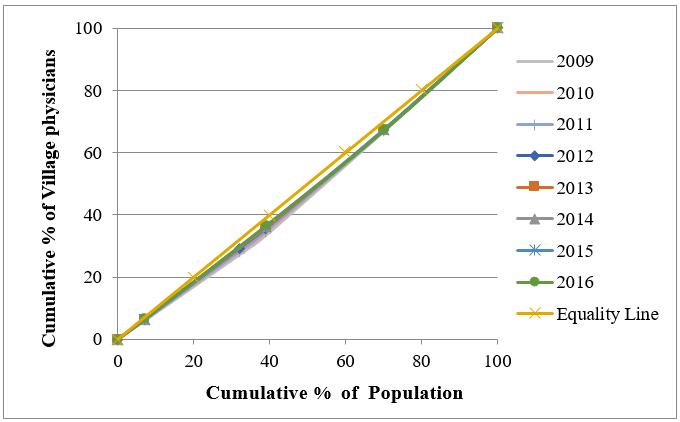

First, the densities per 10,000 rural persons across the four divisions were calculated. Then, the Gini coefficient and Theil L index were chosen to investigate the inequality trends in the densities of village physicians. The Gini coefficient and Theil L index both took values between 0 and 1, with higher values indicating higher levels of inequality10. The Gini coefficient is defined mathematically based on the Lorenz curve, a cumulative frequency curve that compares the distribution in income or other resources among different groups or divisions11. Data limits concerning the rural population size were calculated. All divisions were ranked according to village physician-to-population ratio, and the cumulative proportion of physicians and population in each division was plotted in a plane of coordinates12. The equality line represents a perfectly equal distribution of health workers (ie a division containing 20% of the general rural population size has 20% of the general health workers). The closer the curve is to the equality line, the more equitable the health workforce distribution is. The Gini coefficient has four levels for its value: Gini coefficient <0.2 indicates absolute equality, 0.2–0.3 relative equality, 0.3–0.4 proper inequality, and above 0.4 represents severe inequality13. The Gini coefficient can only calculate the general inequality, not explain the sources of the inequality (which comes from between the divisions or within the divisions). Hence, the study used another method, Theil L index, to measure the sources of inequality.

The Theil L index allows subgroups to be ‘decomposed’ in the context of larger groups. The Theil L index can be divided into two separate components (in this case, the divisions and the provinces), and calculate the overall inequality in two separate parts: a sum of ‘within-group inequality’ (across provinces) and a ‘between-group inequality’ (across divisions) component14. A Theil index of 0 means complete equality, and when it is close to 1, it indicates high inequality15.

The Lorenz curve and Gini coefficient were calculated using Excel. The Theil L index was calculated in MATLAB v2014a (MathWorks; https://www.mathworks.com).

Ethics approval

This study relies on data routinely collected by the National Bureau of Statistics of the People’s Republic of China. No primary data was collected for this study.

Results

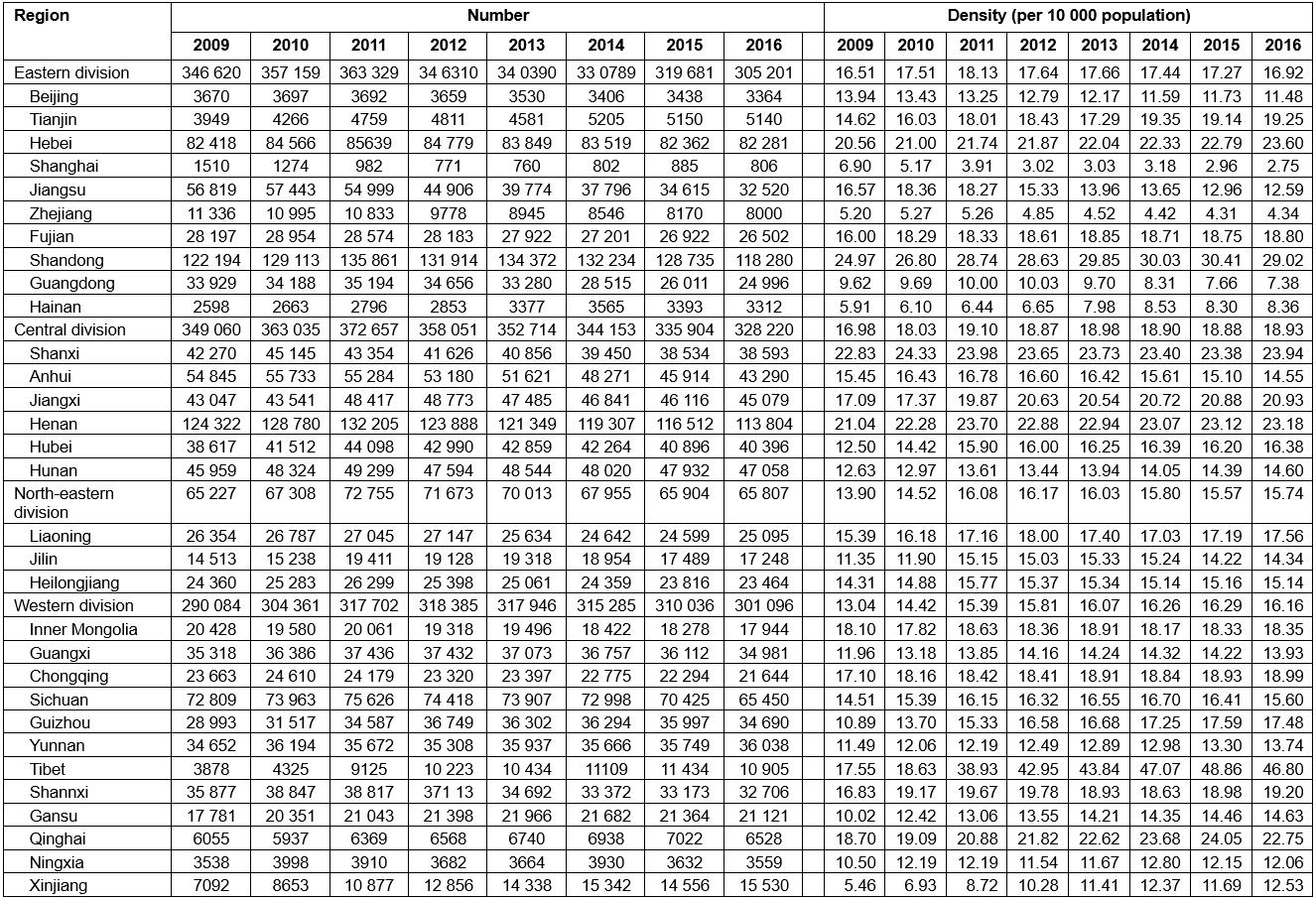

T shows the descriptive statistics of health workforce distribution in rural China, with the total number and densities of health physicians at the divisional level. The number of rural population shows a decreasing trend. In the eastern division the rural population decreased from 209.96 million in 2009 to 180.37 million in 2016, in the central division it shrank from 205.57 million in 2009 to 173.39 million in 2016, in the northeastern division it dropped from 46.94 million in 2009 to 41.82 million in 2016, and in the western division it fell from 222.49 million in 2009 to 186.35 million in 2016. From the densities of health physicians, the ratio of health physicians in rural China was beyond the threshold of one village doctor for each village clinic set by the National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China16. However, in this context, the north-eastern division and the eastern division showed a decreasing tendency in village physicians compared with the other two divisions.

The Lorenz curve in Figure 1 shows the cumulative share of health physicians against the cumulative share of population from 2012 to 2016. Figure 1 shows that at the divisional level the health physicians data indicate good equality. The Gini coefficient (Table 2) for the health physicians declined from 0.062 in 2009 to 0.038 in 2016, which means the health worker distribution is fair.

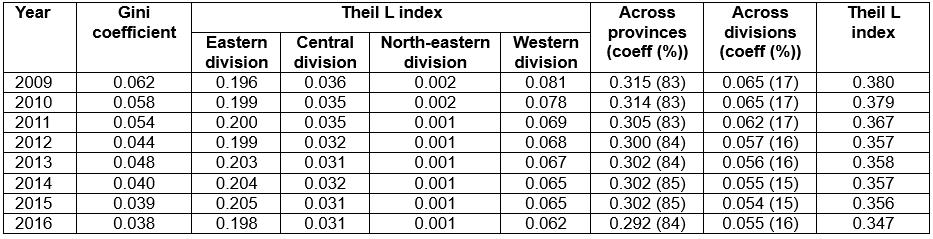

Table 2 shows the decomposition of health physicians based on the Thiel L index. The index, which changed from 0.380 in 2009 to 0.347 in 2016, reflected higher inequality when concerned with the differences between divisions and within divisions. Overall inequality in the distribution of the health physicians between provinces is much higher compared to overall inequality between divisions. Moreover, for the inequality within each division, the eastern division’s Thiel L index is higher than other divisions, which means the inequality in health workforce distribution of those provinces and municipalities within the eastern division is more serious.

Table 1: Numbers and densities of village physicians, China, 2009–2016

Table 2: Inequality in health workforce distribution across divisions and districts, China, 2009–2016

Discussion

The village physician-to-population ratio of the western division was the lowest in 2009. With the decrease in the north-eastern division, in 2016 the village physician-to-population ratio of this division became the lowest one. According to the statistics, the rural population in each division show a declining trend, so the decrease in the density of village physicians was not caused by the increase of the rural population. This can be explained in terms of the worsened economic condition and less financial support to medical and health care in the north-eastern division. According to the data of regional GDP in the Statistical Yearbook of China9, the GDP of the eastern division increased from ¥19 667.441 billion in 2009 to ¥41 018.644 billion in 2016, that of the western division increased from ¥6697.348 billion to ¥1568.217 billion, and that of the central division increased from ¥7057.756 billion to ¥16 064.557 billion. However, the north-eastern division showed slow growth rate and a fluctuation, increasing from ¥3107.824 billion in 2009 to ¥5777.082 billion in 2015, and dropped to ¥5240.979 billion in 2016. By calculating the proportion of expenditure for medical and health care in general public expenditure, the study found that the proportion of medical and healthcare expenditure in the north-eastern division was the lowest (6.95%) in 2016, compared with 7.65% in the eastern division, 9.25% in the central division and 8.39% in the western division. Since the poor economic development in the west of China, the Chinese government has issued many specific targeted development plans and strategies to improve health service there. But the north-eastern division of China did not get as much financial support as the western division. The economic condition of the north-eastern division has deteriorated from the 1990s, when this division, China’s heavy industry base, endured the hardest time after China began to reform and open up to the world, because the technological innovation, outdated machinery and inefficient production led to the bankruptcy of many enterprises of heavy industries17. Under such circumstances, less and less financial support was given to the grassroots level health institutions, which caused the decline in the village physician-to-population ratio.

Except for the change of village physician-to-population ratio, this study found that the source of the inequalities was mainly the differences within divisions by Theil L index decomposition. The inequalities in health physicians across provinces contribute about 83% to 85% to the total Theil L index. For each division, the inequality in the eastern division was most outstanding. In health workforce distribution related studies, the inequality in regions with better economic condition has always been neglected; most scholars and policymakers paid more attention to those less developed regions when they talked about this issue, and the equality in regions with better economic condition was taken for granted. Former studies found that the eastern division had the highest inequality (Gini=0.318) and reached the level of proper inequality in paediatric workforce18, and the eastern division was the least equitable regarding both the distributions of obstetric and gynecological workforce per 10 000 women ≥15 years (Gini=0.200) and per 10 000 women of reproductive age (Gini=0.461)19. The health workforce has flexible career options to stay in high-paid hospitals, cities or urban areas in China, and this may further aggravate this inequality20. The inequality in health workforce, as well as health institutions, leads more and more rural residents to choose to work at these hospitals.

Chinese governments need to think more carefully about the current distribution of health workers either between the divisions or within the divisions. The inequality could account for the shortage of health workers, the disparity in economy, and the government policy priority. In terms of health worker shortage, increasing the number of rural-origin students21 and rural-oriented students admitted to medical schools would be an effective strategy. Also, the government should adjust current policy priority, keeping the financial support in the health service of the western division while strengthening the attention to other divisions.

Chinese village physician distribution is generally equitable. But given the increase in non-communicable diseases and aging in rural China22,23, the unmet needs in health care would be even greater because of the inequitable health workforce distribution. Government should not only optimize the distribution between rural areas and urban areas and different regions, but also pay more attention to the inequality in village physician distribution within a region. Policies that set a limit on the number of physicians in each area according to the population, coverage and health needs would lead to a more equitable distribution of physicians24. The single intervention of increasing village physicians’ remuneration and subsidy to attract more health workforce is not practicable for some regions with poor and stagnant economies The government could take some economic measures, such as changing the current rural health insurance system, promoting the comprehensive economic development within a region, and adjusting the medical education and training system.

Conclusions

This study used Lorenz curve, Gini coefficient and Theil L index to discuss inequalities in health workforce distribution in rural China with data from 2009 to 2016. In this study, within-group inequality (across provinces) accounted for the main inequality observed in the distribution of village physicians. Findings from this study highlighted there were still different types of inequalities in village physicians existing in rural China. The findings in this study can be adopted in making national or regional village health workforce allocation policies.

Given China’s present situation, China’s rural health resources are extremely deficient, compared with other types of human resources for health. Village physicians (village doctors and assistants) constitute the majority of the entire rural health workforce. Therefore, this study did not include other types of rural health workforce in this analysis. Further studies are needed to reveal the detailed sources of inequality and to provide evidence for national and local policymaking.

Acknowledgements

We greatly appreciate the support and advice of the reviewers and editors. This research was supported by Major Program of Beijing Municipal Social Science Fund (No. 17ZDA16). The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. Figure 1: Lorenz curve showing distribution of village doctors and assistants according to population size at the divisional level, China, 2012–2016.

Figure 1: Lorenz curve showing distribution of village doctors and assistants according to population size at the divisional level, China, 2012–2016.