Introduction

This study examined the lived experience of providing services to people accessing the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) in rural areas of the state of New South Wales (NSW) in Australia. As of 2015, 4.3 million Australians reported living with some form of disability1. Disability rates are higher in rural and remote areas of Australia, with 23.1% of people reporting some form of disability in comparison to the reported 16.4% in major cities1. Those living with disability across Australia, including those in rural areas, need to access a variety of health services to improve and maintain their daily function and independence2. Historically, disability services across Australia have been offered through government block funding to government agencies and non-government organisations (NGOs) to deliver services to people with a disability3. In 2010, the Australian Productivity Commission undertook an inquiry into the block-funded disability system and reported the model to be flawed and unsustainable4. In an effort to overcome the failings of this model, in 2013 the Australian Government introduced the NDIS.

The NDIS is funded by the Australian Government and aims to ‘facilitate the development of a nationally consistent approach to the access to, and the planning and funding of, supports for people with disability’4. The NDIS provides funding for people living with disability up the age of 65 years, offering a range of service options under a uniform source and mechanism of funding3 overseen and implemented by the National Disability Insurance Agency. In short, uniform funding aimed to overcome the gaps generated by disability-specific or aged-based funding sources, each with differing eligibility criteria. After a 3-year trial phase, the NDIS was progressively rolled out across Australia from July 2016 and is estimated to be able to support more than 460 000 people living with a disability when completely operational in 20195.

A major change within the NDIS was a shift to individualised funding budgets. This change allows consumers to choose the services and supports that best meet their goals. By changing the way services are offered to people with a disability, the NDIS was expected to have a significant impact on service providers across Australia, including providers in rural and remote areas5,6. A shift to individualised funding saw the withdrawal of block funding to government and non-government services. Consequently, support services including government agencies, NGOs and private businesses were required to adopt a fee-for-service model and compete in a consumer-driven market3.

It was acknowledged that with such major shifts to service delivery there is often imperfection and disjointedness in the implementation of systems such as the NDIS7. Across the disability sector, it was anticipated that there would be an increase in service demand8 through the guarantee of ‘reasonable and necessary supports’5 to all Australians with a permanent or significant disability under the age of 65 years. The government identified the importance of building a diverse and capable disability workforce across Australia to meet a growing NDIS market5. Given the challenges associated with recruiting and retaining therapists in rural and remote areas of Australia, the NDIS is likely to have a significant effect on rural service providers2,9.

It is well established that fewer services exist in rural and remote areas of Australia in comparison to metropolitan areas10. In NSW, the ratio of service providers to population decreases with increased rurality, impacting on people living with a disability in rural areas because they are disadvantaged in their access to health services11. Recruitment and retention of therapists into rural areas is challenging and factors influencing this are well documented in the literature9,12. Lincoln et al2 found issues impacting on the retention of allied health professionals in rural areas to include a lack of professional support, social isolation and better perceived career opportunities in metropolitan areas. In a similar study, Veitch et al13 identified issues perceived to affect service provision as raised by senior staff and managers of government agencies and NGOs in western rural NSW. The issues included overwhelming workloads, a need to travel long distances to service clients and a lack of professional support and supervision13. Ongoing issues with recruitment and retention of service providers into rural and remote areas have generated ‘thin’ markets, limiting choice of service providers for people accessing disability supports, creating inequities based on locality14. Further, ongoing issues with the recruitment and retention of service providers have limited the capacity of the rural disability sector to deliver services and supports to their surrounding communities15.

The foreseen capability of the rural and remote workforce to adopt the NDIS has been discussed in the literature, with concerns expressed towards its capacity to meet the anticipated increase in demand6,10. An evaluation of the NDIS trial sites undertaken in 2016 highlighted an unmet demand for support services experienced by participants living in rural and remote areas16. This report also highlighted staff retention being problematic, particularly for allied health professionals in rural and remote areas16. Considerable attention was given to the rural private practice sector and their anticipated role arising from the NDIS8. Gallego et al8 suggested that if private therapists were supported to upskill and expand their services and supports, the increased demand for therapy services under the NDIS may be met, in part, by these rural private therapists. Nonetheless, there was a recognised need to build the rural workforce not only in the private sector but in collaboration with all disability sector stakeholders5,8. It was predicted that many therapists may need to access disability-specific training to expand their practices in order to effectively meet the needs of those seeking specialist services, and that providers may consequently incur substantial costs because they forfeit earnings whilst attending training8. This may be particularly onerous for rural providers, who are often required to travel long distances to access training and supports9. With the NDIS rollout still ongoing, the impact on rural allied health service providers has not yet been investigated. Therefore, the authors sought to explore the lived experience of providing services to people accessing the NDIS in a rural area.

Methods

Methodology

The research question for this study was, ‘What is the lived experience of providing services in rural areas under the NDIS?’ The aim was to seek in-depth experiential insight into the experiences of NDIS service providers, and phenomenology of practice17 appeared to be most congruent with this aim. Phenomenology of practice seeks to explore everyday experiences and illuminate the meaning of these experiences as experienced by participants18.

Participants

This study focused on the experiences of NDIS providers, specifically allied health professionals providing services in rural areas. Service providers who took part in this study were referred to as participants; whilst it is understood that persons accessing funding under the NDIS are referred to as participants, to avoid confusion they are referred to as clients in this article. Potential participants were accessed through the publicly available NDIS registered providers database. All participants were registered NDIS providers or were employed by a registered NDIS provider in rural NSW and needed to be providing a service in a rural location in NSW, classified by the Modified Monash Model (MMM) as category 3 or greater17. Service providers from areas classified MMM category 1 or 2 were excluded from this study as these areas were not considered rural or remote locations. Each participant was emailed an information package that outlined the research in detail and were invited to take part in the study. After participants returned completed consent forms, they were contacted to arrange a mutually convenient time and place for an interview.

Data collection

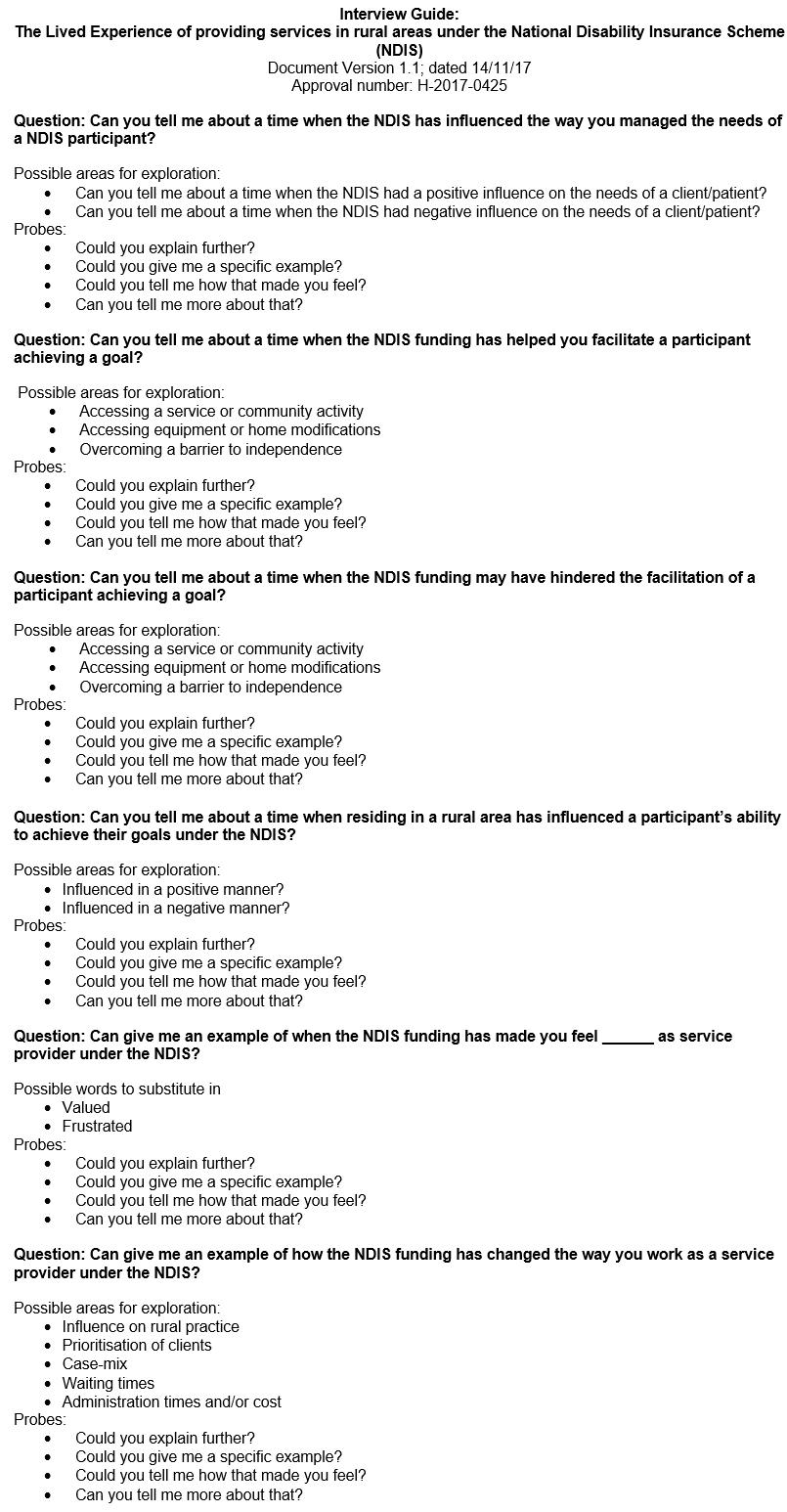

Data were collected from May 2018 to September 2018, 22–26 months after the official rollout of the NDIS in these areas. Individual semi-structured interviews were conducted with each participant. One researcher (RD) conducted all interviews and the majority of the data analysis. Participants were asked about their experiences providing services for clients of the NDIS. The interview guide (Appendix I) was developed by members of the research team who had experience in providing health services within the NDIS and experience undertaking qualitative research. These questions were trialled at two pilot interviews with NDIS allied health providers and were refined based on feedback received. Demographic information was collected with each participant at the commencement of each interview to provide context for their experiences. Interviews were conducted face to face or by telephone, and were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were then analysed thematically.

Data analysis

Data analysis was guided by phenomenology of practice19. The analysis focused on participants’ accounts of everyday lived experience. Each interview transcript was read and listened to concurrently to gain an understanding of the interview as a whole and to reflect on emotive and non-verbal aspects of the interviews captured in the field notes, but not explicitly represented in the transcript. Each transcript was then re-read phrase by phrase and each phrase assigned a code of meaning. The codes of meaning were reflected on and compared across interviews and with the analysis as a whole. Emerging ideas were considered as the transcripts were re-read to ensure that the emergent ideas were reflected in the data. The analysis was discussed with all members of the research team, so that the analysis was considered from other perspectives. From this dialogical process emerged a description of the lived experiences, including the themes. This was written as a vocative text to describe the phenomenon in a way that would encourage a deeper understanding of the lived experience20. Data management was facilitated using NVivo v12 (QSR International; http://www.qsrinternational.com).

Rigour

In this study, credibility was facilitated by conducting peer debriefing during data collection and analysis within the research team to ensure a range of perspectives were considered. Transferability was enhanced by collecting and subsequently describing the participant demographic data. To facilitate dependability and confirmability, process and reflection diaries were maintained by the researcher to provide an audit trail and to document an emerging understanding of the phenomenon under exploration. The reflection and process diaries were also used to aid reflexivity by identifying and explicating the influence of personal biases and preconceptions on data collection and analysis.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Newcastle Human Research Ethics Committee (approval no. H-2017-0425).

Findings

Participants

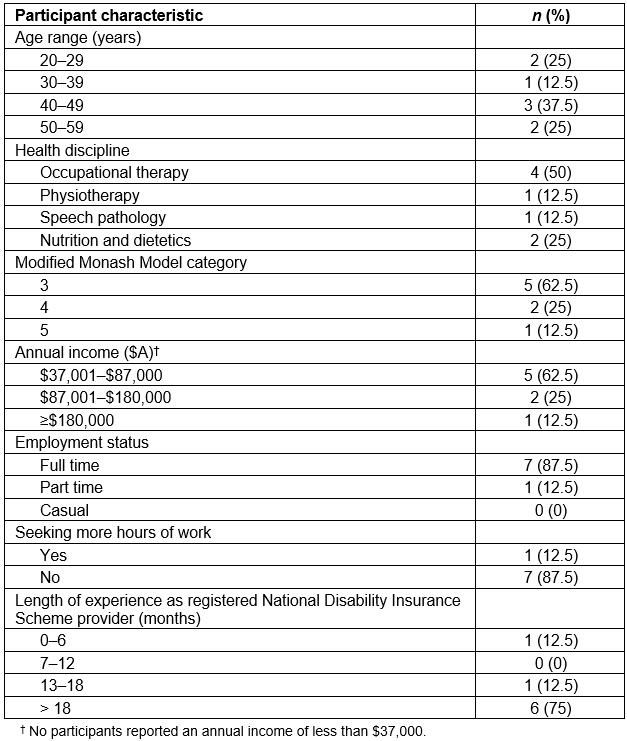

Eight service providers, representing four allied health disciplines from a range of rural and remote locations, were interviewed. Demographic data is presented in Table 1. Participants reported residing and working in a range of rural and remote areas of NSW. Although no participant identified as providing services in areas categorised as MMM category 6 or 7, these areas are considered remote or very remote communities and are predominantly serviced by outreach multidisciplinary teams15,17. All participants were female and had bachelor-level qualifications in their respective health disciplines. No participants reported masters- or doctorate-level qualifications. No participants identified as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander.

Table 1: Demographic information for participants (n=8)

Thematic analysis

Analysis of individual interview transcripts was undertaken while concurrently reflecting on the research question and aim of the study: to explore the lived experience of providing services to people accessing the NDIS in rural NSW. Three themes emerged: (1) ‘Beyond my depth’, (2) ‘A sea of uncertainty’ and (3) ‘Drowning in the wave’. Through further reflection on these themes and the participants’ account the essence of phenomenon was illuminated and is described as ‘Powerlessly facing the wave of change’.

1. ‘Beyond my depth’: This theme described service providers’ experience of a shift in roles as a consequence of the NDIS. This shift in roles came as a result of the move to individualised funding, which positions people living with disability to self-advocate throughout the process of applying for funding, agreeing upon required supports and accessing appropriate services. This was described by an occupational therapist:

Pre-NDIS, we [service providers] would do all the work … but now it’s actually up to them [the clients] to actually fill out forms, follow-up with NDIS, get all that happening, organise plan reviews, sign papers, decide what they want and how they’re going to do it. (Occupational therapist, MMM3)

Similarly, a dietitian explained how funding packages were allocated with minimal input from service providers:

There’s no consultation with clinicians about what services they can provide or how much funding they should be allocating towards certain services. (Dietitian, MMM3)

Participants emphasised that appropriate self-advocacy and health literacy skills were essential if their clients were to receive adequate funding plans. Through past experience, and having established relationships with many clients prior to the NDIS, many participants acknowledged that clients and stakeholders were not always equipped with the knowledge, skills or self-confidence to navigate the NDIS and self-advocate for the services and supports they required. One occupational therapist explained how a child’s level of funding was often reflective of family and contextual circumstances:

If the parent doesn't have the skill … if their own mental health or emotional health is not so fantastic or perhaps haven't got an education level … then children do miss out. (Occupational therapist, MMM3)

Participants acknowledged they were spending more time coaching their clients and stakeholders about the self-advocacy skills necessary to navigate the NDIS. One dietitian conveyed a sense of detachment between the clinician and funding process:

I give them lots of information, the patients – we go ‘here’s all your information. These are the words you need to say’, and I hope that they say it correctly and they get the plan, or they don’t get the plan. (Dietitian, MMM4)

This advocacy for vulnerable clients struggling to negotiate the NDIS system was burdensome for participants and a source of ongoing stress and frustration. An occupational therapist described how one of her clients in need of intensive supports had, despite the advocacy of the participant, received an inadequate funding plan:

It’s really distressing to know that this child would actually be able to achieve a lot more than they are but because of the way that the NDIS is funded … he’s not given the opportunity. (Occupational therapist, MMM3)

The experience of advocating for a client who was subsequently not provided the supports they needed was distressing for participants, particularly as the reason for the perceived inadequacy of funding was possibly not a reflection of the needs of the client resulting from their disability, but their ability or inability of the client to self-advocate within a complex system.

2. ‘A sea of uncertainty’: This theme described the experiences of service providers in relation to the perceived inconsistency demonstrated by the NDIS. Participants raised concerns about inconsistencies in the level of funding their clients were receiving despite similar diagnoses and needs. Participants attributed these inconsistencies to variations in experience and knowledge among planners and local area coordinators. One occupational therapist stated:

Some of them [the clients] certainly have less funding than those [the clients] that have certainly less needs and I guess the other frustrating thing is it seems to be related to who their [the client’s] planner ends up being. (Occupational therapist, MMM3)

Similarly, a speech pathologist stated:

… some people might get a really good plan and be higher functioning than someone who is more severe or lower functioning and getting a very poor plan because there isn’t consistency amongst the local area coordinators. (Speech pathologist, MMM3)

Participants also spoke frequently of inconsistencies in their communication with the NDIS. An occupational therapist stated:

If you call the NDIS to ask them a question ... you’ll get five different answers from five different people. (Occupational therapist, MMM4)

Participants perceived that one of the issues was a lack of health literacy among NDIS planners and local area coordinators, which created uncertainties in funding outcomes for their clients. One speech pathologist stated:

… it’s around the educational qualifications for the person making quite monumental decisions for families and not having the advocacy skills to get the best for that client. (Speech pathologist, MMM3)

To accommodate this uncertainty, participants were often required to provide their clients with supporting documentation for NDIS planning meetings. Participants expressed frustrations about this process because funding plans were frequently returned with little reflection of their clinical recommendations:

… you might do a report and submit it to the family to give to their local area coordinator … and the plan comes back completely ballsed up because that person hasn’t had the comprehension about what speech and language and cognition’s about. (Speech pathologist, MMM3)

Many participants shared similar experiences of their attempts to support the review of NDIS plans having little influence. As a result, despite holding deep concerns for the inevitable impact on their clients, participants were exhausted in their efforts and had considered closing books to NDIS referrals. The comments of one dietitian illustrated this:

I’m at the point where I don’t know if I’ll take any more NDIS people on because the whole process of the documentation and dealing with the plan coordinators is getting to the point where I’m getting a little bit annoyed with it all … but my concern is where do these people go? (Dietitian, MMM4)

When clients were able to receive adequate funding and support there were positive outcomes for the client and the participant. A speech pathologist spoke of how adequate funding was seen to greatly benefit clients:

… some children that probably wouldn’t have received funding prior to the NDIS or would’ve got a very minimal amount of funding or its allowed us to really go in, you know, very strict, very robustly and do more intensive therapy … so that’s been really positive to actually make some really effective changes. (Speech pathologist, MMM3)

Thus participants indicated that this positive result was related to this client being fortunately managed by an NDIS planner with a strong understanding of the client’s needs. It was clear that the vagaries of the NDIS system were stressful for participants because of the impact this had on the clients under their care.

3. ‘Drowning in the wave’: This theme described how most service providers had noticed a significant increase in referrals as many people with disabilities were receiving first-time funding through the NDIS. This was seen as a positive to some extent, because some clients who might not previously have had access to funding could now have it. Yet these rural service providers were already managing services that were in high demand. This increase in service demand threatened the viability of the services as participants struggled to meet it. One occupational therapist had closed her books to new referrals:

… referrals have tripled in the last 12 months so that’s the main reason for closing books. (Occupational therapist, MMM3)

Another occupational therapist spoke positively of a client who was receiving first-time funding; however she went on to speak of her inability to find vacancies in her caseload due to an overwhelming increase in service demand:

We have a lot more kids who have intellectual disability and older kids … getting funded therapy services for the first time … it’s positive but because of the sheer demand, I just don’t have the appointments. (Occupational therapist, MMM5)

One participant spoke of her decision to close her books and discussed the ethical dilemma this can present in smaller rural communities. She stated:

I find it extremely difficult to say no to someone … I live and work in my small community so I know everyone, they know me. (Occupational therapist, MMM3)

Despite having reached clinical capacity, she conveyed an increasing sense of guilt about not having the capacity to meet the local demand for services:

I felt like I didn’t want to answer the phone, I didn’t want to return phone calls … It does feel like, I want to hide away a little bit. (Occupational therapist, MMM3)

These accounts suggested that overwhelming increases to service demand with the NDIS were affecting not only the perceived identities of rural service providers in their workplace, but also their perceived sense of self as members of the communities.

Participants also spoke about needing to access further training to broaden their clinical skills. Access to the NDIS has altered the case mix of participants, necessitating the need for them to seek further training and upskilling. A speech pathologist explained:

I’ve had to probably broaden my skill base. Prior to the NDIS I didn’t do a great deal of intellectual disability work so I’ve had to upskill in that area. (Speech pathologist, MMM3)

Similarly, a dietitian stated:

I’ve had to seek out more information. I’ve also done a recent workshop on mental health. (Dietitian, MMM4)

In many cases, additional training was achieved through the use of online resources as access to face-to-face training for service provider in rural areas is often difficult, and more time-consuming and financially burdensome. Most participants were grateful for the opportunity to broaden their scope of clinical skills; however, they voiced concerns over the increased complexity of many referrals. This too was attributed to changes to funding eligibility with the NDIS. Overwhelming, participants held concerns on two fronts: the increased psychological impact of complex cases on the therapist, and a lack of continuity of services for clients with less complex needs. An occupational therapist illustrated this:

We’re getting more children with more significant disabilities … There’s a lot of emotional energy I feel goes into those sessions a lot and, paired with that, we’re not really seeing those children who are a bit milder … which is a shame because a lot of the children who could really benefit are not getting a service at all. (Occupational therapist, MMM3)

Participants reinforced that their concerns were centred on a greater percentage of complex cases among their overall caseloads, which was perceived to magnify the overall psychological impact of their day-to-day work. In many cases, this was perceived as burdensome because participants often felt isolated and less supported as a therapist in a rural area. An occupational therapist expressed her concerns:

… from a supervision or mentoring perspective, where do we get support as a therapist, where do I find support as a therapist. It’s quite challenging – because there isn’t any. (Occupational therapist, MMM3)

It was apparent that participants were not only overwhelmed physically in relation to the number of cases they were capable of taking on, but were also nearing psychological capacity. This was powerfully illustrated by an occupational therapist:

I might say I’ll give it another 12 months [as a registered NDIS provider] but I feel like I’m burning out with it. I’m not prepared to have this level of intensity for much longer. (Occupational therapist, MMM5)

Many providers were overwhelmed by an overall increase in service demand, compounded by the psychological impact of a larger portion of complex cases. Participants discussed issues of having fewer local service options, which compounded feelings of guilt knowing their clients were not receiving sufficient services and supports. Poignantly it was not the NDIS clients who felt unsupported and isolated but the participants themselves, who were struggling with the demands of close-knit rural communities.

‘Powerless facing the wave of change’: The essence of the phenomenon of providing services within the NDIS in a rural area was identified as ‘Powerlessly facing the wave of change’. The ‘wave of change’ represents an evolving NDIS and its impact on service providers. It encompasses a shift in role for service provider and changes to the magnitude and nature of service demand. In isolation, the ‘wave of change’ lacks depth in understanding the lived experience of rural service providers working within the NDIS. The true essence of the investigated phenomenon emerges when intrinsic responses of rural service providers facing the ‘wave of change’ are considered. Challenges associated with service provision in rural areas overwhelmed the ability of participants to adequately meet the demand for services. This often led to emotional stress felt on behalf of clients not receiving adequate services and supports. A notable increase in the proportion of complex cases further challenged the psychological capacity of many participants, with many feeling isolated and less supported as rural therapists. Participants conveyed notions of lost autonomy and passivity, which reflected an inability to act with influence in the face of change. This was powerfully illustrated by an occupational therapist and thus the true essence emerged as being ‘Powerlessly facing the wave of change’:

I often sit back and look and think what is this system doing to these families? (Occupational therapist, MMM4)

It is concerning that, despite the ideology of the NDIS as empowering people with a disability and their families, in rural areas of NSW this initiative is being experienced as disempowering and distressing by those who are implementing the support and care that the NDIS was developed to fund. Furthermore, what is evident from these accounts from rural clinicians is that they feel powerless working within a funding system that is hindering their ability to meet the needs of their clients.

Discussion

Participants in this study overwhelmingly reported negative experiences with the NDIS, which they attributed to several factors centred around the need to adapt to ongoing and unpredictable change.

Participants held profound concerns for many of their clients who they felt were being insufficiently supported by their NDIS planners or local area coordinators. The experiences of participants in this study appear to align with those identified in a broader survey of over 1500 NDIS-registered service providers in 2017, with few providers perceiving the NDIS to be having a positive impact on participants, their families or the workforce delivering disability supports21. Participants evidenced their concerns by describing repeated issues with consistency of funding among clients. They felt these issues were the result of inexperience and varying levels of education among those coordinating client supports. Identified issues with inconsistency across funding plans and increased administrative burden were congruent with those found in a broader survey of the Australian disability sector in 201822. For an individualised funding model such as the NDIS to take effect and benefit those it aims to empower, both service providers and clients require ongoing access to high-quality local information and support in collaboration with funding coordinators23. Those managing the supports of clients particularly in rural and remote areas require a thorough understanding of the needs of those living with disability, and need to understand the added complexities of service provision in geographically isolated areas24. Yet, evident in discussion with service providers, they felt disengaged with those coordinating funding supports and additionally felt that many of their clients were unsupported by their planners despite a crucial need for advocacy.

Providers discussed changes to the nature of their cases, with many seeking further training in response to increased referral of clients with intellectual disability and mental ill health. Participants primarily utilised online resources when seeking further education due to the complexities of accessing face-to-face training in rural areas, as previously highlighted by both Veitch et al13 and Keane et al25. Providers acknowledged that many NDIS participants were receiving first-time funding, and expressed gratitude for the opportunity to expand their knowledge and provide services to a wider variety of clients. Despite these opportunities many providers were overwhelmed by a notable increase in the number of complex cases. The psychological impacts of such changes were amplified by perceived isolation and reduced professional support in rural areas. Isolation of rural therapists, particularly those working in private settings, is often considered a double-edged sword: on one hand therapists have greater autonomy and on the other they experience a lack of access to professional support26. The NDIS has resulted in an increase in service demand to private practice, and these providers are less likely to work in team environments. Critically for existing rural providers, their accounts of increased complexity among cases indicates a crucial need for added professional support to avoid further isolation and additional psychological strain.

Service providers noted significant increases in service demand, particularly for people with complex disabilities requiring higher levels of support, which they felt had compounded their pre-exhausted capacity to meet service demand. Historically, issues with recruitment of new therapists into rural and remote areas have resulted in unmanageable workloads for existing service providers and long waiting lists for clients seeking services and supports2,13. Hence, the need to build the rural and remote workforce was widely acknowledged and viewed as crucial for the NDIS to take effect and support those requesting services5,8. It is concerning that the accounts of participants in this study indicate that the predicted increase in service demand has been realised in rural areas without concomitant growth of its encompassing workforce. Whilst unmet service demand in rural and remote areas was identified in the NDIS trial site evaluation16, findings in this study indicate this issue remains despite ample opportunity to address this concern in geographically isolated areas. This indicates that issues with recruitment and retention of therapists into rural and remote areas may be becoming increasingly dire, potentially widening inequities based on geographical location with continued rollout of the NDIS.

In these existing ‘thin’ markets in rural and remote areas, individuals already geographically disadvantaged in their access to services were unlikely to be able to exercise true choice and control under an NDIS14. This foreseen concern was affirmed through the accounts of service providers in this study who held concerns for people accessing NDIS services in rural and remote areas, providing deeper insights into a pre-existing inequity based on locality within the newly introduced NDIS. Further cause for concern relates to participants in this study providing accounts in which they contemplated deregistering their supports under the NDIS as they were nearing physical and psychological exhaustion. Unsettlingly, future growth of the rural and remote workforce to address the needs of those funded by the NDIS may be threatened by the overwhelming pressures on existing service providers.

A strength of this study was that experiences were examined from a diverse range of participants who represented a range of health disciplines, ages, experiences and rural and remote areas of practice. Semi-structured interviews allowed participants to discuss topics that were meaningful to their own experiences. In this study it was only feasible to interview participants once. This meant there was not the opportunity to inquire about participants’ comments further or check that they felt their interview reflected their lived experience. No participants identified as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander, which may limit the transferability of findings. Importantly, Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people account for 6.4% of Australia’s rural population in comparison to 2.6% in urban areas27. It is known that the provision of health services to Aboriginal people by Aboriginal health providers is one strategy that may improve health outcomes, thus it is important to understand the perspectives of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander service providers28. Findings in this study may vary from areas of Australia where the NDIS has been established for a longer period. Future research should encompass a wider geographical footprint to determine if experiences are consistent in other states. It is also essential that the perspectives of other NDIS stakeholders are explored in depth in particular NDIS clients and their families and carers.

Conclusion

Despite being committed in their roles as service providers, participants struggled to meet the increased demands of providing services within the NDIS. Participants in this study had difficulty adapting to requirements of the scheme and indicated that their experiences were frequently compounded by working in rural and remote areas. Concerningly, the existing rural and remote workforce appears at a greater risk of physical and emotional exhaustion, which further threatens the viability of services in rural and remote areas of Australia. Recruitment and retention of new therapists into rural and remote areas, and the provision of added supports for existing service providers, appears critical to avoid failings of the NDIS in rural areas.

Acknowledgements

This research was undertaken as part of an undergraduate honours program completed in partnership with the University of Newcastle Department of Rural Health.