Dear Editor

Following publication of our study comparing the costs of two models of care intended for rural Aboriginal communities in New South Wales, Australia1, we have analysed the data comparing scope of practice between the two models. By way of background, Aboriginal people are less likely to access dental services than other Australians2-4. It is well established in the literature that enhancing access to and use of services by Aboriginal Australians requires tailoring to local needs, customs and language; ensuring staff are culturally competent; and having explicit strategies to promote and sustain participation2-7.

Our retrospective study of 2 years of patient data compared two models of service delivery designed exclusively for Aboriginal people. Model A (fly in, fly out) included a fixed clinic in a major city and visiting services to rural areas. Model B (community based) located clinicians within rural communities and existing community facilities (health clinics, schools, Aboriginal health services). We previously reported the cost and outputs comparison, which found model B provided 47% more treatment at 25.2% of the cost1. We are now reporting on the scope of practice differences between the two models. Scope of practice has been selected as a proxy for effectiveness because treatment that requires several service visits over time enables behavioural change and implies patient engagement in the service8,9.

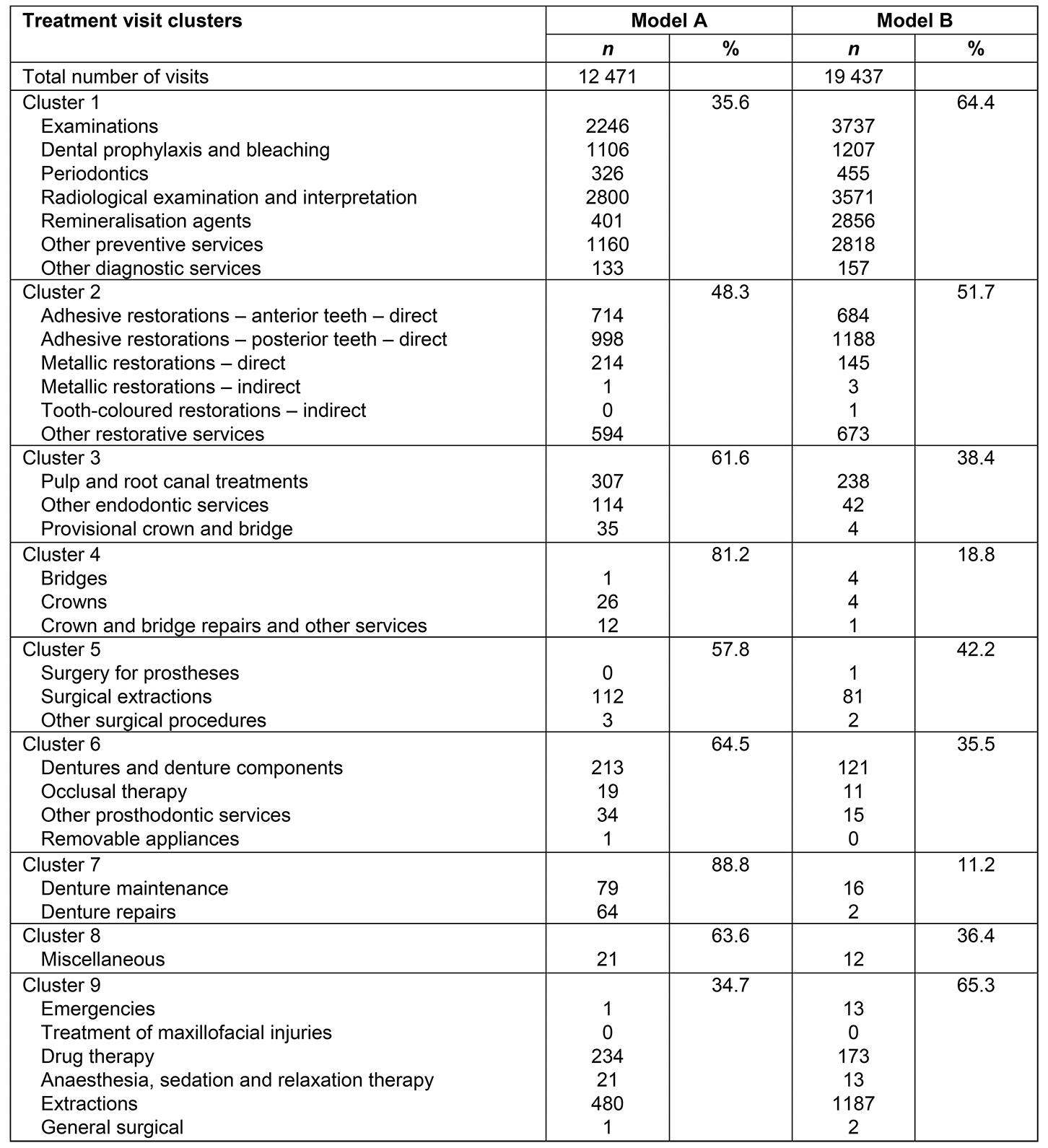

This study compared the scope of practice, measured in grouped dental item numbers using the Australian Dental Association schedule of services, for the two models. De-identified patient dental item numbers for models A and B related to the provision of dental services to Aboriginal public patients were clustered according to typical service groupings and analysed for the period 1 January 2014 to 31 December 2015. Data were recorded for nine clusters of care as shown in Table 1.

There were marked differences in the clusters of treatment for the models over the 2-year data collection period. Model A is more focused on complex clinical care while model B has a higher proportion of preventive care items (Table 1). For example, practitioners involved in model A performed 61.6% of endodontic care performed in the cohort, 81.2% of crowns and bridges, 64.5% of denture care and 88.8% of denture maintenance. The proportions for model B for these items were 38.4%, 18.8%, 35.5% and 11.2%, respectively. The patients in model B received almost double the proportion of preventive care items than those in model A (64.4% v 35.6%) and also received a much greater proportion of emergency care (65.3% v 34.7%).

There are at least three possible explanations for the greater proportion of preventive services delivered by model B. First, the care was provided by a combination of newly graduated oral health therapists and dentists with a specific focus on prevention and early intervention. This could explain the greater use of preventative care items than the fly in, fly out team. Second, the provision of dental care, especially preventive care, requires a relationship of trust between the patient and provider. This is particularly important in Aboriginal communities, where there is a limited choice of providers. Trust is difficult to build with a fly in, fly out service as different providers may visit each time or the visits are sporadic.

Third, model B involved practitioners based within the region, enabling the same individual practitioners to deliver services on a regular basis. The rapport built up by this regular presence is likely to have established a level of trust such that, when the emergency and acute dental treatment needs of patients were met, they were willing to come back for follow-up care. In addition, model B employed local Aboriginal staff in administrative and dental assisting roles which was likely to enhance both trust and the cultural competence of the service.

Aboriginal people have twice the rate of untreated dental caries compared with other Australians3. Preventive care services are therefore a very important aspect of oral health care7,8. Model B provides a greater level of preventive care and other ongoing services, which may be attributed to the community-based approach.

Table 1: Clusters of treatments and number and percentage by service model

Kylie Gwynne, Yvonne Dimitropoulos, Boe Rambaldini and John Skinner, Poche Centre for Indigenous Health, The University of Sydney

Katrina Poppe, Senior Research Fellow, University of Auckland

Debbie McCowen, CEO Armajun Aboriginal Health Service

Anthony Blinkhorn, Faculty of Medicine and Health, The University of Sydney