Introduction

Most of the Amazon region population living outside urban areas and big cities is subject to precarious living and health conditions. These circumstances result from how these people have been exploited over time, which generally demonstrate a disregard for their interests1. Investments have been made in the Amazon region to expand large-scale livestock, soy production and extractive activities, such as logging, mining, oil and gas exploration and construction of hydroelectric plants, but, in general, these actions operate in an exploratory logic that, in addition to being harmful to the environment, violate local communities’ rights2.

The areas of environmental degradation ‘coincide’ with social degradation areas, which further exposes people to vulnerable situations and, consequently, health risks3. The literature cites access to potable water, lack of basic sanitation, infectious diseases, exposure to toxic products, and high nutrition-related disease rates as common problems in this region4-8.

These conditions are aggravated by the Amazon being marginalized by domestic policies of Amazonian countries, which exclude the region from national plans and dynamics9. This situation contrasts with the importance of the Amazon on the global stage because it accounts for 56% of the world’s rainforest and 20% of its freshwater flow.

The Amazon is in South America, covering an area of 6 million km2 in nine countries. Its coverage is distributed in those countries as follows: Brazil (58.4%), Peru (12.8%), Bolivia (7.7%), Colombia (7.1%), Venezuela (6.1%), Guyana (3.1%), Suriname (2.5%), French Guiana (1.4%), and Ecuador (1%)10. It is characterized as a biome predominantly composed of forest located in the Amazon River’s hydrographic basin. Despite that, the Amazon is not homogeneous but consists of different areas that result from the interaction of its physical aspects with the population diversity that inhabited this region at different times in history11.

The literature shows how parts of the region gained importance because of the natural resources to be explored12. This resulted in the occupation of the territory, which has contributed to the formation of large urban centers and places where a greater financial and political capital is concentrated in relation to most of the region, which consists of a mosaic of farms, villages, isolated houses and small towns spread over a vast territory, often accessible only by river, and that can be considered remote because of the difficult access. As a rule, these places are inhabited by Indigenous peoples. These peoples include a wide variety of groups, who, depending on where and how they live, are known as ‘villagers’, ‘mestizos’, ‘river people’ or ‘caboclas’13.

The historical development of this region and the transformations that it has undergone, also marked by inequalities in the distribution of power, prestige, and resources, has contributed to the presence of health inequities in the region, which can be observed in the lack of resources and public policies, including health policies, in areas outside the urban centers or that are not being economically explored. This reality has contributed to the limited access to health services, especially high-complexity services, that are usually offered in larger cities14,15.

In most South American countries, primary health care (PHC) has been strongly influenced by selective PHC models. In those countries, the vertical health programs focusing on specific diseases and not on the global needs of users were common between the 1980s and 1990s16. One result of this process in health policy was to increase privatized services and adopt a market-oriented approach with minimal economic interventions targeted at specific groups17. These policies have led to a general lack of support for a more comprehensive PHC model and have increased social inequities18. It was common for the poorest and rural populations to be harmed in this model19.

However, in the first decade of the 21st century, several countries in South America experienced processes of renewal of PHC that have sought once again to adopt a comprehensive PHC approach that is closer to the Alma-Ata2 concept. Countries such as Bolivia, Brazil, Ecuador, Peru, and Venezuela began to adopt new PHC models that have common features: a family approach, comprehensive care, and a community approach with multidisciplinary teams in specific territories with specific populations.

A study focusing on PHC in South American countries has reported effective results in the performance of PHC related to improving health conditions, but challenges and problems in its implementation process were also pointed out20. Giovanella et al highlight the challenges of reaching remote and disadvantaged areas in South America18.

In the Amazon, some studies have reported disorganized distribution of healthcare services and the lack of PHC services14,21, and findings showed that those most excluded from services in Amazon are mainly vulnerable and socioeconomically disadvantaged populations22.

The absence and difficulties of PHC performance in the Amazon causes concern because studies have found improvements in health indicators associated with the implementation of PHC23. Furthermore, in rural and remote areas, care recommended by PHC has been considered strategic to meet the needs of these territories24. Its relevance in these locations is emphasized, given its importance for reducing morbidity and mortality25. PHC is also considered ideal when caring for traditional populations in rural and remote areas26.

Given the relevance of PHC in the Amazon and the difficulties of health policies to prove effective when facing this context27, the aim of this review was to map the studies in the literature that have addressed these issues, identify the ways in which PHC is implemented, analyze its potential to reduce health inequities in locations outside urban areas in the Amazon, and identify gaps that can guide future research and help plan service improvements in this region.

Methods

Because of the complexity of the issue and that it has not been reviewed previously to any extent, this study adopted a scoping review methodology. By using the protocol proposed by Arksey and O’Malley28, the main concepts of the area of study were mapped, and existing gaps in evidence were identified. The understanding gained from the mapped studies was then synthesized in accordance with the method described by Levac et al29.

In view of the study objectives, this review proposed the following question: ‘How does PHC function and what are its strategies in the Amazon and their respective potential to reduce inequities?’. In this study, the concept of PHC followed the approach defended by Vuori30, which presents at least four ways of understanding PHC: as a set of activities, as a level of care, as a strategy of organization for the service system, and as a principle that should guide all the actions developed in a health system. The search keywords were identified, considering these statements.

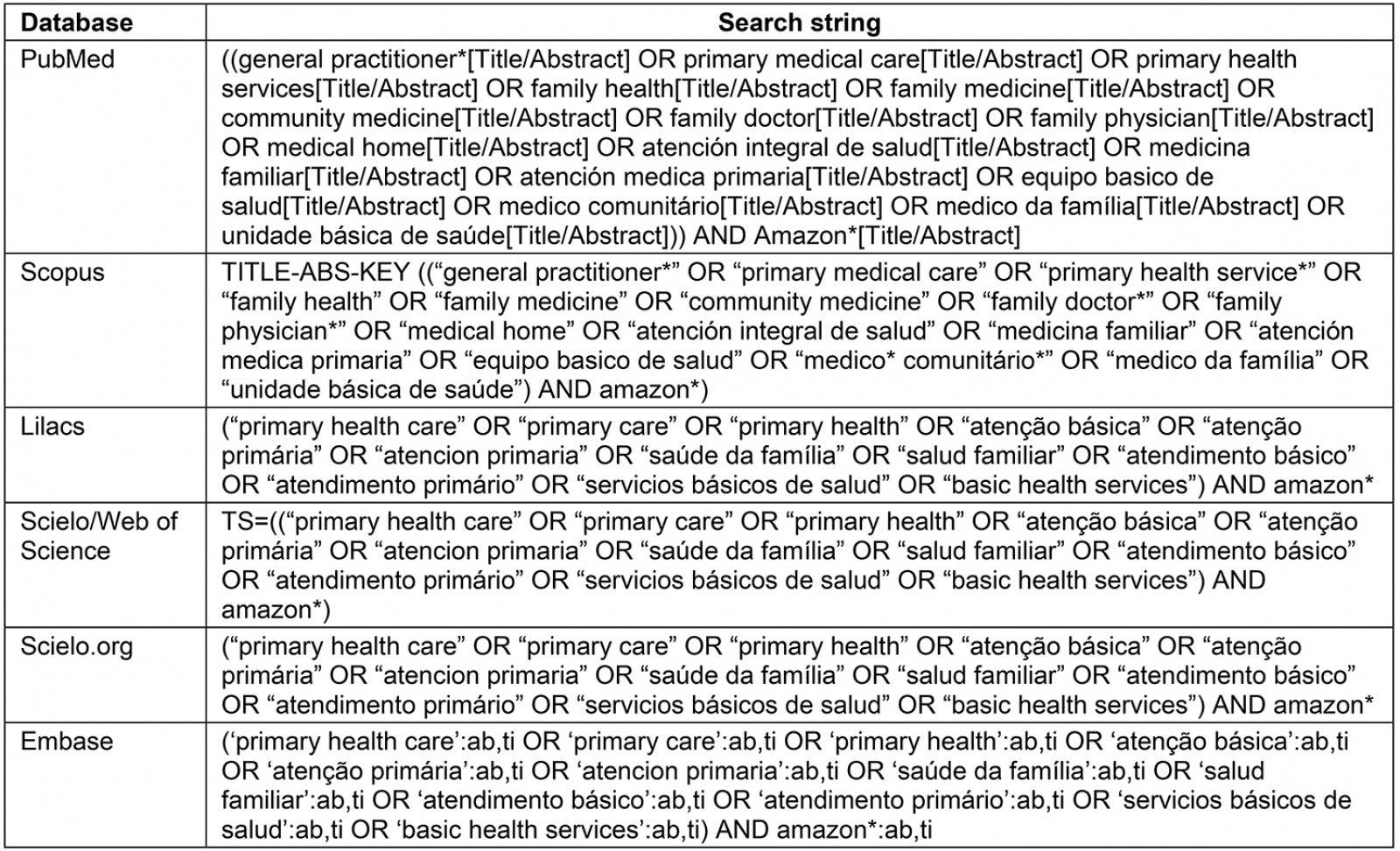

The search keywords (Table 1) were identified through consultations between the researchers and a health science librarian and a scan of the titles and subject headings from the results of the preliminary search. All the studies in the databases were limited to the languages spoken by the team members (English, Portuguese and Spanish) and a publication date between January 2000 and November 2019.

For this review, especially as it focuses on a specific ecosystem in which the territorial characteristics are not limited to commonly held ideas about rural life, the decision was made not to use the term ‘rural’ as a search criterion, but instead use the term ‘Amazon’, opting to include the studies about PHC in the Amazon provided they were not limited to the urban areas in this region.

The databases searched were PubMed, Scopus, Lilacs, Embase and Web of Science between June 2019 and November 2019. The bibliographic information for each search result was imported into Covidence (http://www.covidence.org). Subsequently, duplicate articles were removed and the abstracts were reviewed.

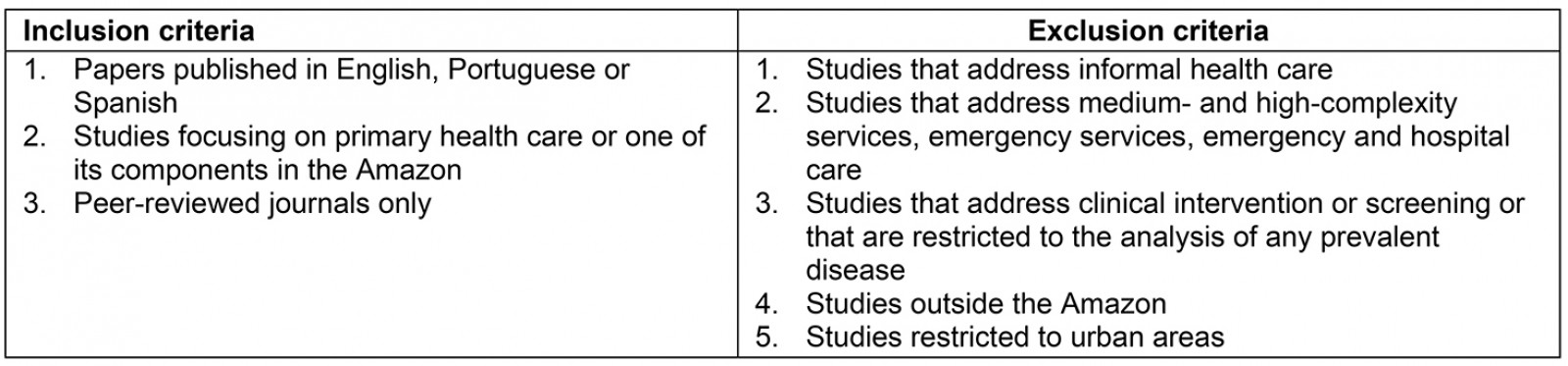

The titles and information on the abstracts in these records were reviewed independently by two researchers; studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria or any of the established exclusion criteria were excluded (Table 2). Only studies published in peer-reviewed journals were included. Where there was disagreement about eligibility, one of the authors who had not participated in the first phase of the review gave their opinion, and then the other authors reread the item, and the final decision on inclusion was made in a group meeting. Studies were not excluded on quality grounds but purposely included to map available evidence as consistent with the scoping review methodology.

After that, three authors read the complete articles and reviewed them independently. During this process, the reference lists of included studies were also evaluated, resulting in the selection of no additional studies. The authors created a spreadsheet model with predefined codes that was shared among reviewers for data extraction. During data charting, some codes were adjusted, and other codes were added to the spreadsheet. That resulted in the following information being collected for each article: author, year of study, objective, country, method, how rural is described, PHC strategy/actions, positive impacts, and negative impacts. Then, each article was summarized and classified according to content.

This process enabled visualization of the scope and discussion among the team, resolving any disagreements about content allocation. Following this, content analysis was performed in accordance with the theoretical reference used.

Table 1: Keywords for electronic database search 2020

Table 2: Inclusion/exclusion criteria for scoping review papers

Ethics approval

Because this work was a literature review and relied on secondary materials, it did not require ethical review.

Results

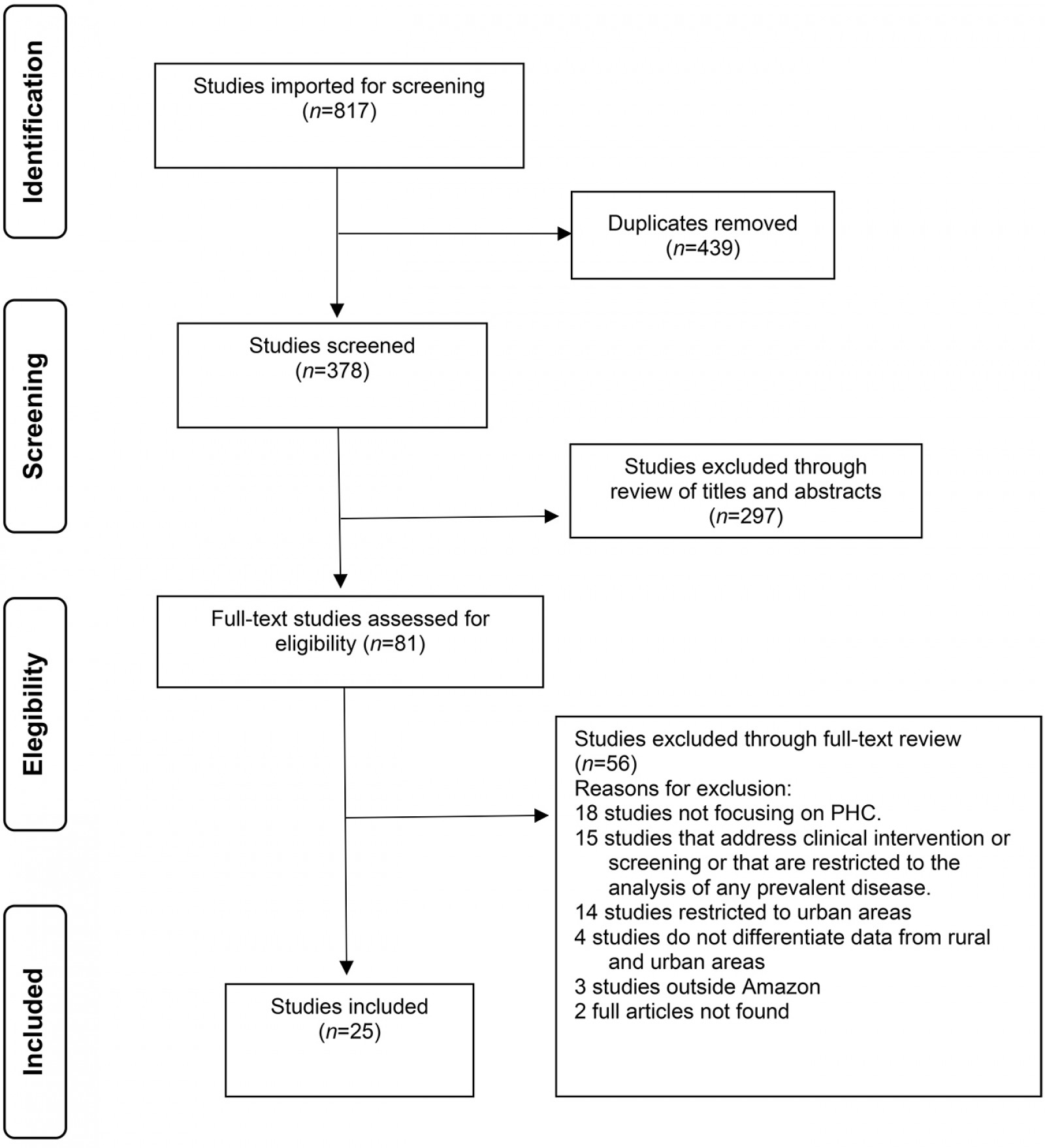

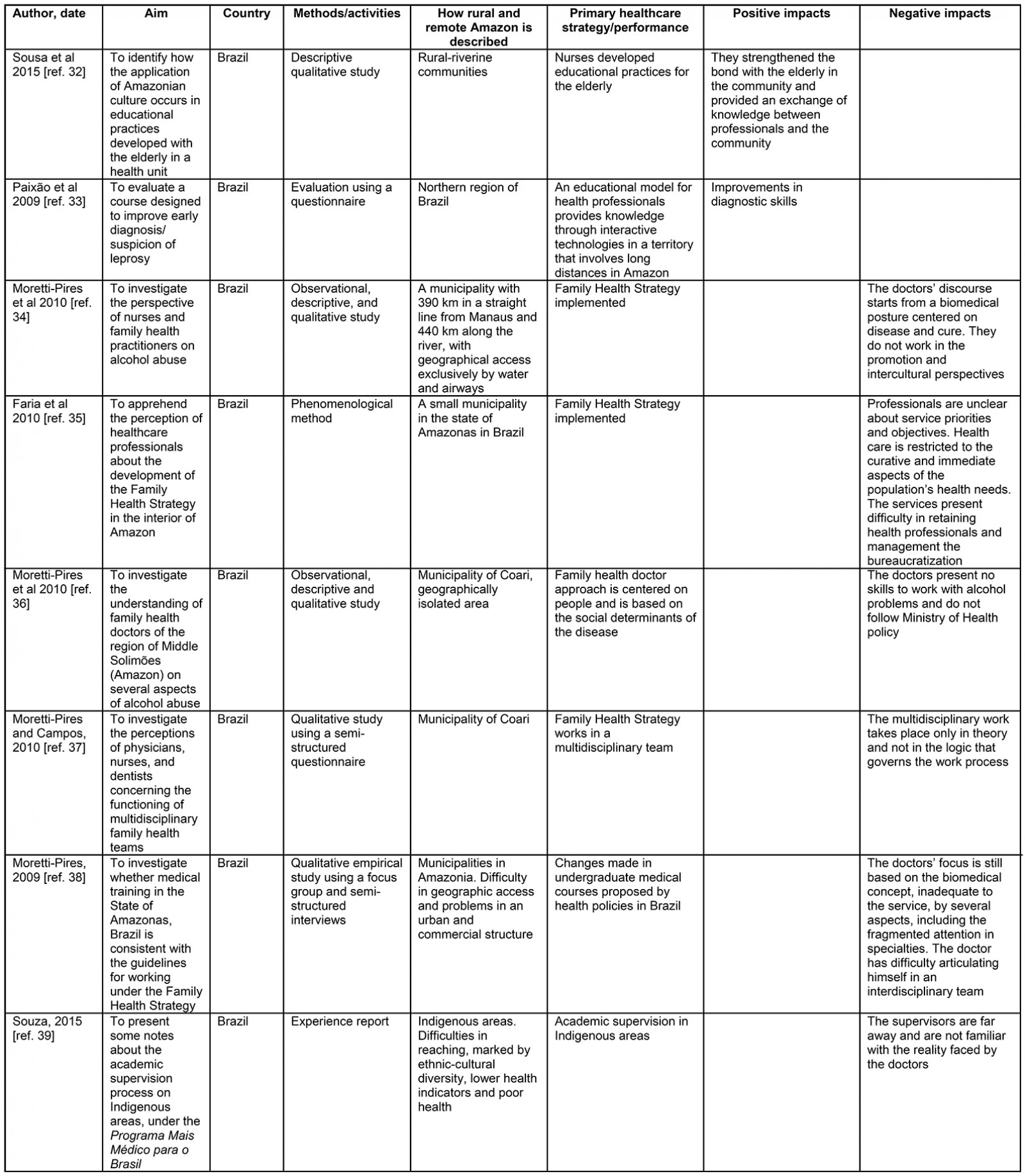

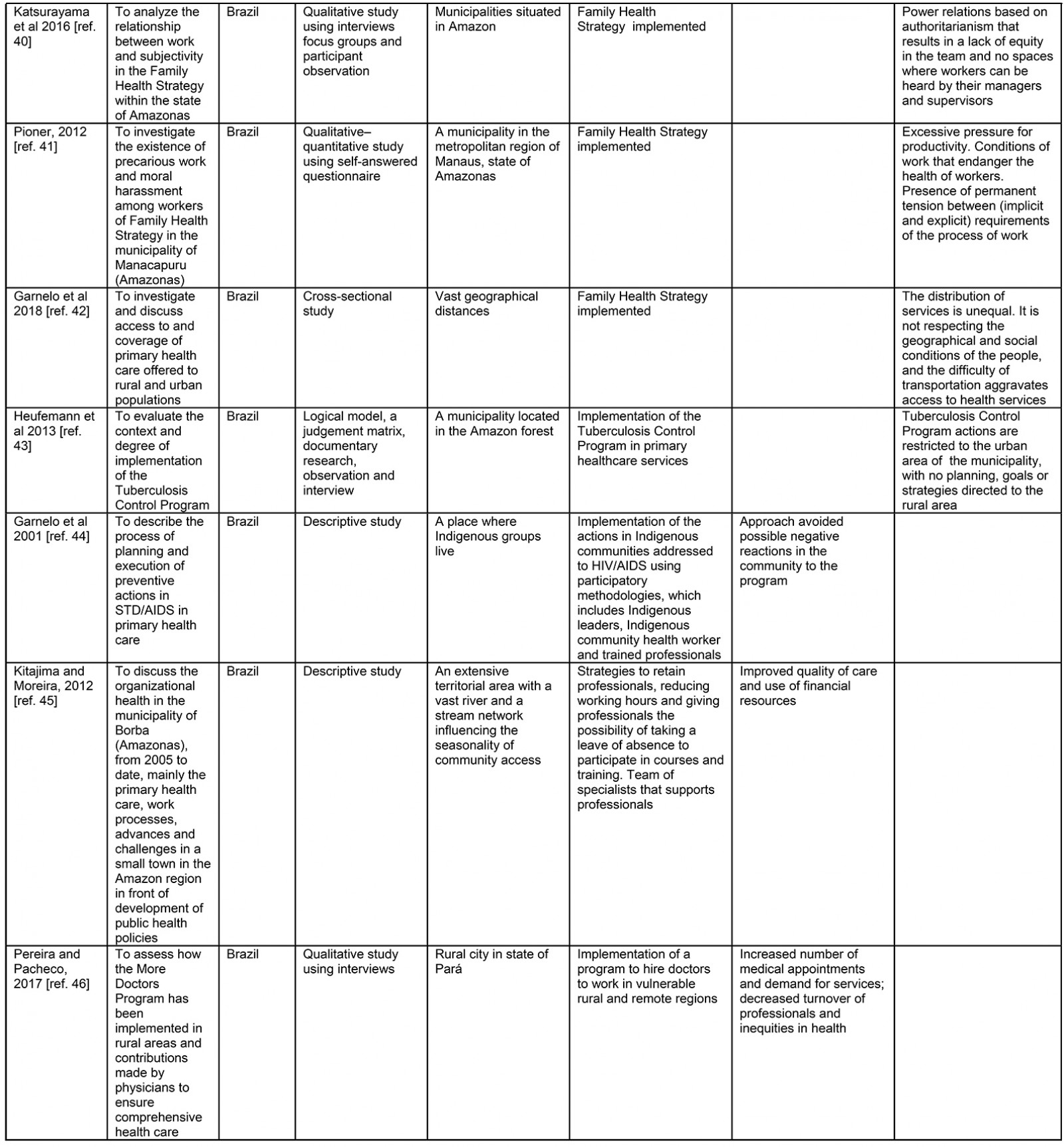

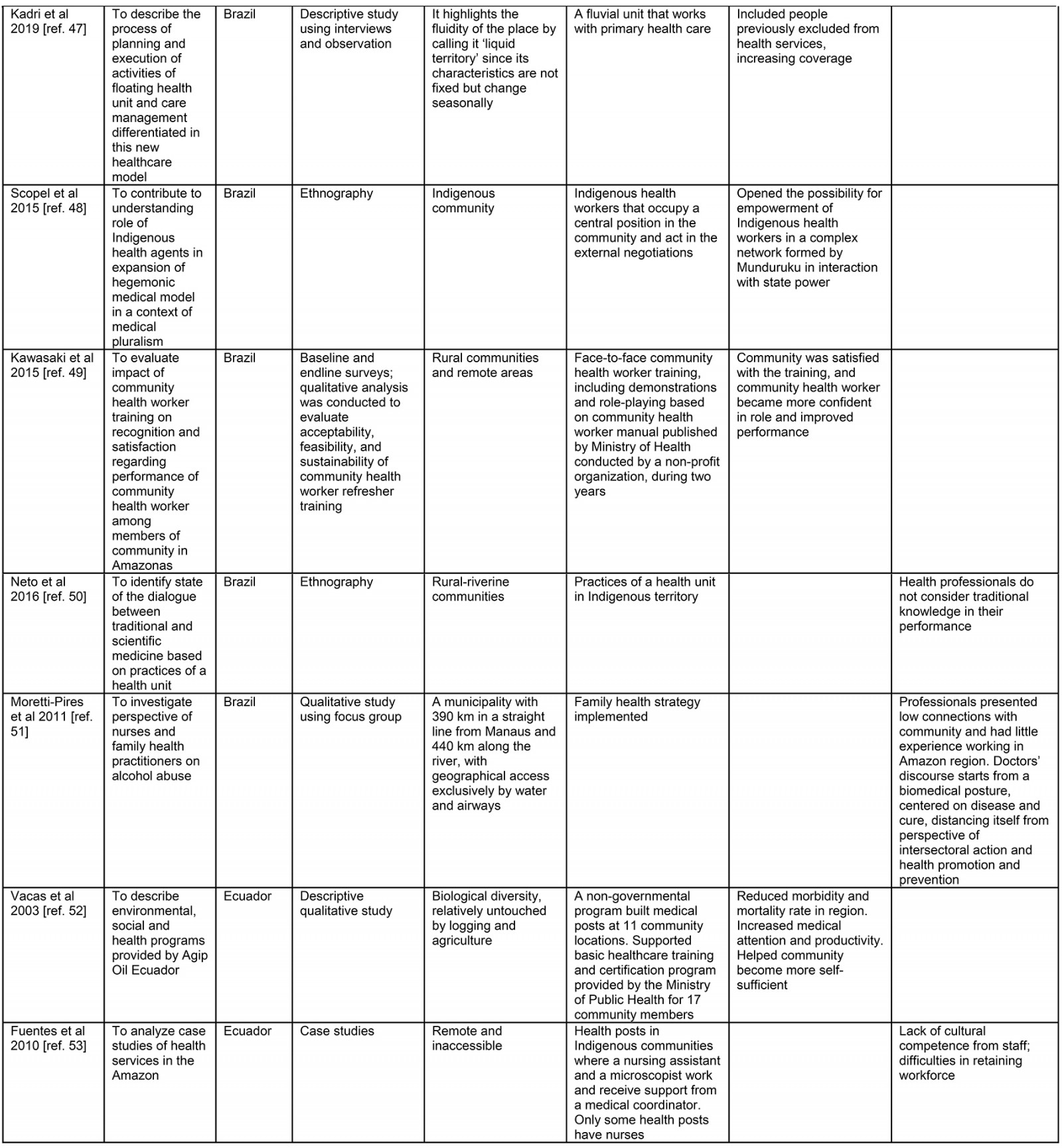

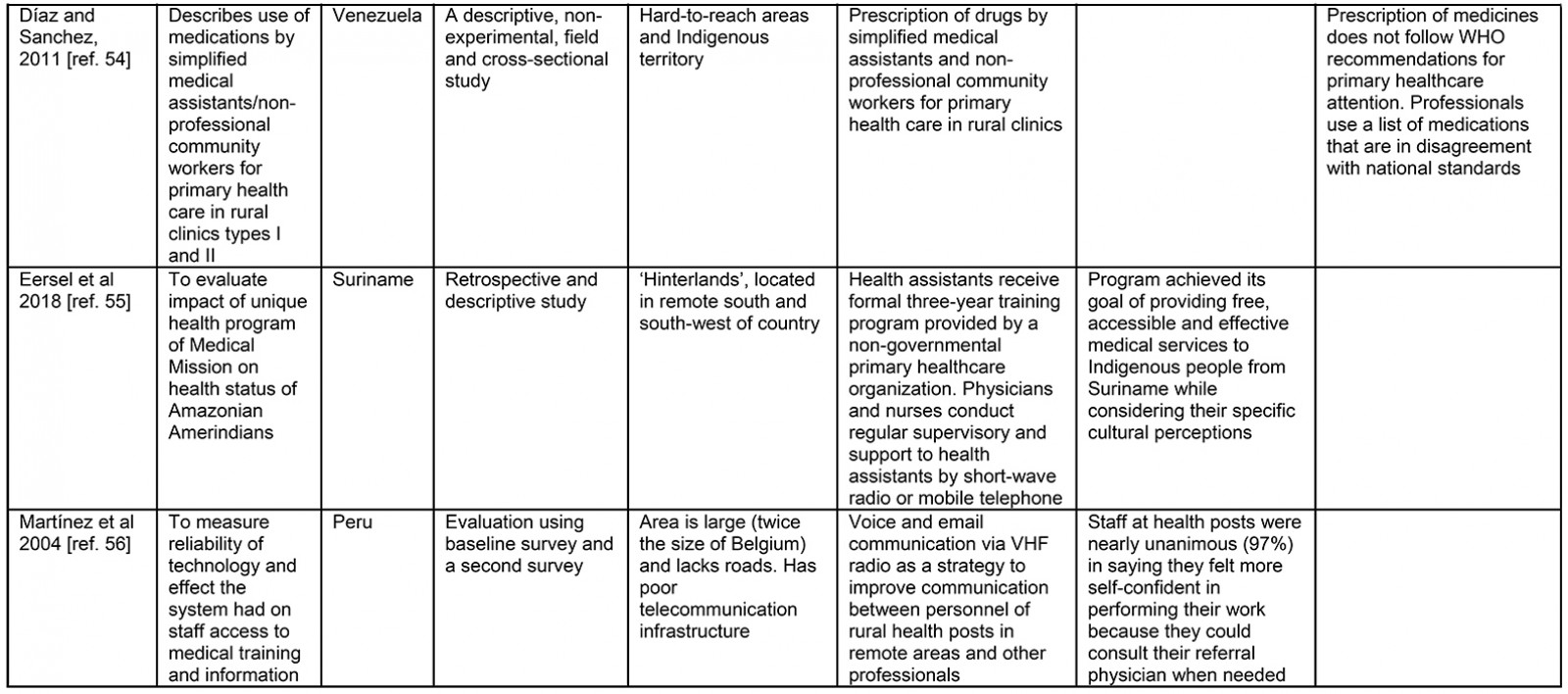

The database search returned 817 results. Following the removal of duplicate articles, 378 unique records remained for possible inclusion in the review. Those papers abstracts were then read, leaving 81 studies for the researchers to read in their entirety and independently, after which 25 studies were included (Fig1). Table 3 shows the main characteristics of each included study.

Figure 1: Flow diagram for the scoping review process.

Figure 1: Flow diagram for the scoping review process.

Table 3: Data extraction sheet31-55

Study locations

Of the articles included, the majority originated in Brazil31-50, followed by Ecuador51,52, Venezuela53, Suriname54, and Peru55. As well as registering the country where the PHC services took place, this review prioritized how the authors referred to the study location. This characterization was important because of the different landscapes and population groups of the Amazon. Most authors referred to the study location as ‘small municipalities’ (n=9). Other terms used by authors to designate the place were ‘Indigenous areas’ (n=7), ‘rural/remote’ (n=3), and the ‘region of the country’ where the study took place (n=2); while other authors used characteristics to describe the place as a ‘várzea region’ (floodplain) (n=2). One of the studies that also referred to riverbank areas gave more emphasis to the aspects of the population groups that inhabited the place, referring to it as a ‘fishing community’ (n=1) and one of the studies referred to the place as ‘interior’ (n=1).

Implementation of actions and strategies adopted by primary health care

Of the 25 studies, 11 of them31,32,43-48,51,54,55 revealed promising results regarding PHC implementation and strategies. On the other hand, 14 studies presented results that highlight difficulties and challenges to be overcome33-42,49,50,52,53.

Impacts on access

Based on the PHC actions implemented and their respective results in the studies (Table 3), six studies suggest that the implemented actions successfully broadened access. These actions include:

- use of technology to support and supervise community health workers (CHWs) and nursing technicians51,54,55 that helped provide services in isolated areas that do not have other health professionals

- measures taken by policies and management to organize and adapt the services and retain medical professionals in remote areas44,45,51 that increased the number of medical attention and the demand for care

- performance of a new health unit model that operates aboard a boat46, which included people previously excluded from health services and increased the number of people with health assistance.

However, in two studies, the PHC actions and results indicate a possible increased difficulty in access to services. One of them41 analyzed the access and coverage in urban, rural and remote areas. This study revealed services concentrated in urban areas, and their design did not consider the vast distances, population dispersion, and financial expenditure imposed on users. Another study42, which focused on the context and degree of implementation of the Tuberculosis Control Program in PHC services, found that the actions were restricted to the municipality’s urban area and revealed no planning, goals, or strategies to the rural area, despite presenting disease cases.

Impacts on quality

Twelve studies pointed out implemented actions and results that showed flaws in the quality of services. These findings appeared in studies that investigated PHC services. Four studies focused on actions and strategies related to the approach used by the services 33,36,37,50 and presented the work with individual care, focused on the disease and did not consider the reality of families and the sociocultural context. Three studies were dedicated to the performance of professionals considering their previous academic education and training34,35,53 and found professionals poorly prepared to work in the PHC services and contradictions between what is expected and what is done by professionals in the services. Four studies described the service management34,38-40 and found problems in supervising, monitoring actions and managing professionals’ relationships. Two studies investigated whether the services were working with a cultural approach49,52 and found that the health professionals did not consider the traditional knowledge in their performance.

Nine studies presented results that suggest positive impacts on the quality of services. Five of them referred to training or other strategies used to prepare the professionals32,44,48,51,54, which resulted in qualified professionals to work. One of the studies dedicated to monitoring the activities and support to the professionals44 showed how these actions can contribute to improving the quality of care and the use of financial resources. Four studies were addressed to investigated the adoption of culturally appropriate approaches by services31,43,47,54 and found facilitated ties with the community. One of the studies focused on the approach of implementing an STD/AIDS program in an Indigenous community and described the use of participatory methodology43 that avoiding a possible resistance to the program.

Impacts on community empowerment

Engaging community members in the construction of and decision-making for PHC actions appeared in one study47 that showed the participation of Indigenous health agents in both local health groups and regional health groups.

Discussion

The findings of this review revealed that few studies have focused on PHC in the Amazon. However, another problem was identified: the unequal distribution of these studies. As this review shows, most studies were conducted in Brazil, and few studies were conducted in other Amazonian countries. No studies were found in Bolivia, Colombia, Guyana, or French Guiana. Despite the difficulty of research in countries with low income, it is in these countries that research in PHC is the most necessary56. Notably, the diversity of terms used by authors of the studies to refer to the location reveals that there is no single way of referring to places in the Amazon outside the urban centers.

The studies found in the review, in general, focused on the functioning of free-of-charge public health units, projects and actions in rural areas of the Amazon. The actions and strategies addressed by the studies were part of the list of daily activities in these units. Some studies described projects developed in these units by policies especially established for rural or Amazonian areas. It is noteworthy that some actions and strategies were carried out by various actors, including non-profit organizations, foundations and programs developed by universities.

Most studies were conducted in healthcare units that are part of the Brazilian program Family Health Strategy. The Family Health Strategy was implemented in Brazil in 2006 and is the main primary care initiative in the country. These healthcare units follow the same healthcare model all over the country, with no differences between urban and rural areas, serving as a gateway to the entire health system. The teams of health professionals (general practitioner, one nurse, one or two nursing technicians and four to six community agents) are placed in strategic geographical locations57.

In countries other than Brazil, the health units portrayed have a specific operation model in rural areas, grouped into health posts and health units. Health posts are typically located in isolated areas and composed of CHWs or nurse practitioners, who are usually assisted by doctors from health units. Health units are located in a provincial or district capital and are made up of doctors and nurses. A common feature of the health posts is that they are located over scattered areas and serve a smaller number of people18.

The actions and strategies of PHC, as well as the results, reveal that most of the PHC implementations face difficulties and challenges. Nevertheless, some studies reported promising results and suggested that the strategies of PHC were effective in the Amazon region.

It is important to recognize the actions that have contributed to a better performance of PHC, as well as the strategies and actions that still present problems, both for the relevance that the PHC has in improving people’s health conditions58 and for its role concerning health inequalities, since it is considered the most effective model in reducing health differences in society and in promoting equity59. To achieve this result, the PHC must meet the following requirements: the PHC team should be highly accessible, and focus on high-quality and networked operations with other sectors to increase social cohesion and empowerment60.

Previous studies have shown that improvement in access, in Latin American countries, results in better health conditions. For example, a study conducted in rural areas of Bolivia reported that mortality rates were four times lower in areas assisted by PHC than in areas that did not receive assistance61. Confirming those studies, the results of this review also showed positive impacts on rural Amazonian areas due to an improvement in access. Also, this review showed that the total number of PHC actions in the Amazon that had a positive impact on access was higher than those that had a negative impact.

Among these results, one of the studies demonstrated the importance of using radio and cell phones, making it possible for more educated professionals to support CHWs and nursing practitioners in isolated locations where they must work alone. It also slightly reduced the feelings of professional isolation of part of rural healthcare personnel. One of the studies suggested that health units using this strategy reduced the morbidity and mortality rate in a remote community in the Amazon region. That is particularly relevant in Amazonian countries where rural health units are composed of only CHWs or nursing practitioners, and communication is difficult because of their isolation. In this regard, there is a recognized impact of the presence of these workers on communities in disadvantageous conditions in Latin America62, where they are considered a link between rural community members and other providers of health services63.

However, some actions have demonstrated the potential to negatively affect access. These were related to how services are geographically arranged and how they are provided in rural areas, which in some cases accentuate differences between places, potentially increasing inequities. For example, one study presented the imbalance in the distribution of services between urban and rural areas in the Amazon, and another showed problems in retaining the workforce. These are everyday situations in rural Amazon and demand action from managers to overcome these differences. One example is the imbalance in the number of doctors available in urban and rural areas in the Brazilian Amazon, which needs policies and management measures to be overcome64.

Although the number of studies with negative results regarding access was lower than the positive, the number of actions with negative results regarding quality was higher. The findings of this review demonstrate that the quality of services remains a challenge for PHC in the Amazon. Findings in this area reveal problems related to the cultural adaptation of services, inadequate approaches, poor preparation of the workforce and problems in service management. Among the negative impacts on the quality of the services, the most recurrent results are related to the use of a biomedical approach by health professionals and problems in the management of services.

Despite the effort to adopt a comprehensive healthcare approach by health policies in the South American countries, this review shows the use of a biomedical approach rather than a ‘whole-patient oriented’ one65. This can be explained by the strong market-oriented influence in these countries66. However, Starfield67 states that a health system focused on subspecialization threatens equity goals because subspecialty care is too expensive, and countries cannot afford the cost of distributing this type of service to everyone.

Another issue that was most often related to negative impacts on the quality of PHC services was limitations in manager performance. Management performance plays a key role in conducting PHC services in rural areas. Studies that showed these results presented difficulties for managers in carrying out inspections, monitoring the results of services, supporting professionals and implementing services68.

Some of the actions described in the studies demonstrated improved service quality. These studies were often related to the education and training of professionals, the most frequently cited being CHW training. The studies suggest that when CHWs are trained, they become important allies for the quality of services in Amazonian areas. These results have also been found in prior studies, which highlights the importance of these professionals in rural and remote areas69. However, problems in the preparation of CHWs to work in PHC showed they could put the populations they serve at risk; for example, by distributing medicines without proper guidance. This review also indicates that the higher-level professionals had a deficit in their training, according to their actions and the results of the studies, evidencing contradictions between what is recommended and the work execution in Amazon.

The culturally appropriate approach was considered the most important characteristic of the PHC services in the study with Indigenous people26, but some studies in the review still presented negative results in this regard. Not paying attention to or not adapting the services to cultural differences tends to unbalance the power between the population and health professionals in rural areas. According to Malatzky70, the power relations that unroll in rural and remote settings must be carefully considered because of the prevalent understanding of the fragilities of such settings, with healthcare actions often reproducing and reinforcing that type of relation.

Despite health policies in Latin America adopting strategies that have shown good results by engaging people to control and participate in the development of health services71, only one study described the engagement of people as a strategy used by the PHC services in Amazon. The lack of studies with similar orientation is a challenge for the PHC services in these areas, since community engagement has been recognized as one way to offer quality and sustainable PHC actions in remote areas72.

Also of note in the findings is the gap in PHC actions that involved external partnerships in their implementation, which is understood to be essential for a less fragmented PHC that responds better to the inequities. This review also identified in PHC actions a lack of strategies aimed at modifying health determinants, which in this region primarily involve social and environmental issues. It is also of note that this review did not find evidence of any PHC strategies that demonstrated, prior to the service implementation, a concern with the impacts on inequities, a strategy that Freeman et al73 identified as significant when implementing PHC services.

Strengths and limitations

This scoping review is the first attempt to comprehensively synthesize and describe the published literature on PHC in the Amazon. A second strength is that the review included studies in Portuguese, Spanish, and English, which broadened the scope of the research to provide significant coverage of the available literature.

One of the limitations of this review is that it focuses only on peer-reviewed articles and probably did not include valuable documents from the grey literature. Also, since none of the included studies reported the effectiveness of their interventions or measured the impact on inequities, the analyses were based on the results presented by the authors about the general aspects of the PHC in the Amazon and interpretations about what has been exposed by the literature about this topic to reach the conclusions presented here.

Conclusion

As an initial study exploring the existing literature about PHC in the Amazon, this review has produced useful findings. It has exposed forms of PHC implementation that appear to have promising results, indicating the paths to be followed by public health policies, health managers and professionals in the Amazon region.

The results highlight the benefits of actions that expanded access to PHC given their ability to adapt to the singularities of the place, such as the policies for the provision of professionals in remote areas, the strategies used by managers to retain professionals in the Amazon and the health unit model adapted to the river. These results reinforce the need to recognize, given the heterogeneity of this region, that one-size-fits-all policies are insufficient and specific solutions are required that respect the singularities of the place.

Investment in training and the use of technologies by CHWs have shown promise in the region. However, there are still uncertainties and insufficient knowledge about the ideal performance of this professional group. The Indigenous health agents are workers specific to the Amazon region. As found in the review, they can mediate traditional and biomedical knowledge, providing a less unequal power relationship between professionals and Indigenous people. However, both the CHWs and the Indigenous health agents need to be recognized by public policies. Research that addresses their performance can help outline the possible roles they can play according to the needs and singularities of each place.

The difficulties and challenges reveal that, despite the efforts of some Latin American countries to adopt comprehensive approaches in the training of professionals in academic courses, it is still necessary to strengthen public policies in this direction and prepare professionals to work in Amazonian areas. It must include training in approaches that promote the openness of these professionals to provide care that is culturally appropriate, comprehensive, holistic and accessible. Further to this, qualified managers are required to support and supervise the professionals.

The review exposed gaps in the research that has been undertaken or at least published, including a lack of studies of strategies aimed at health determinants. There was also a lack of evidence of work involving community engagement and partnerships developed with other actors in the community. In this sense, there is an urgent demand for research and policies to prioritize these themes since they are fundamental strategies in the face of the threats to the health of people living in the Amazon.

Acknowledgements

This study has been supported by National Council for Scientific and Technological Development, Brazil, and the Foundation for Research Support of the State of the Amazon PPSUS/01/2017 EFP_00014168, Brazil. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection or analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.