Introduction

Chronic disease accounts for much of the health gap between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples and the broader Australian population1. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples also experience substantial inequities in access to primary health care. Innovative, culturally safe strategies to improve access to high-quality chronic-disease care and prevention are needed to address these disparities2.

Medicare-rebated Indigenous-specific health assessments, or the Health Assessment for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People (Medicare Benefits Schedule Item 715), known as 715 health checks, have been introduced to improve limited preventative health opportunities and reduce rates of undetected risk factors among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples3,4. Current international evidence suggests that the value of preventative health checks aimed at the general population is not supported by the best available evidence5,6. However, there is an emerging body of evidence supporting the importance of structured health assessments for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples.

Recent audit evidence of more than 17 000 client records across 137 Indigenous primary healthcare centres has demonstrated the important impact on individuals, particularly with regard to several domains of preventative health7. Individuals had three-fold higher odds of being tested for sexually transmitted infections and to receive counselling if they had recorded an Indigenous-specific health assessment8, and four-fold higher odds of being assessed for cardiovascular risk9. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children had 33–66% higher odds of being screened for social and emotional wellbeing if they have received an Indigenous-specific health assessment, compared to those who received acute care10.

Uptake of 715 health checks and follow-up services has been poor to date7,11. This poor uptake raises questions about the effectiveness of health check delivery in its current form. The literature suggests the low uptake of 715 health checks can be attributed to a range of system, patient and provider barriers12-14. Tailoring the implementation of 715 health checks to address these barriers is important in addressing poor uptake and health inequities among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people15.

Programs that deliver 715 health checks in a community event, known as Health Check Days, have been trialled by research groups and health services as a potential method to increase uptake of 715 health checks, deliver health information to community, build relationships with local health services and plan for the delivery of preventative health services. However, little literature has been produced that supports or explores the belief that community events increase the uptake of Indigenous-specific health assessments to date. Despite this, there is an emerging body of evidence that Health Check Days have the potential to have a significant impact on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander individuals and communities.

In one example from Northern Queensland, a Health Check Day program targeted at sexually transmitted infection screening found that the prevalence of these conditions appeared to have halved at 2-year follow-up screening16. Another program in a metropolitan setting found that Health Check Day programs appeared to be successful in increasing personal health awareness, facilitating brief intervention and referrals and reinforcing the role of Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services in maintaining the health and wellbeing of the community14. The evidence of benefit extends to identifying and managing risk behaviour across geographical settings17.

At the time of review, the critical aspects of the relationship between community events and the uptake of 715 health checks is unclear. Current literature draws from a range of types of evidence, with the key factors of community engagement and knowledge gaps not identified to date. The nature of this emerging body of evidence lends itself to a scoping review to identify more specific questions that can be posed and valuably addressed by a more precise study. This review aims to explore how community events have been used to increase uptake of Indigenous-specific health assessments. We expect this review will underpin a larger study to better understand how community engagement supports increased uptake of 715 health checks.

This review was undertaken by third-year medical student and first author (JM) undertaking their 14-week research block. The student was supervised by the last author, EW, who is an Aboriginal academic working with local Aboriginal community-controlled health services on the north coast of New South Wales to understand and then implement community Health Check Days.

Methods

Study design

The scoping review was conducted in accordance with the Joanna Briggs Institute methodology for scoping reviews18. This was guided by the methodology framework developed by Arksey and O’Malley19 and enhanced by Levac and colleagues20. This framework describes an iterative process that includes identifying the research; identifying relevant studies; study selection; charting the data; collating, summarising and reporting the results; and consultation. Specifically, the systematic scoping review method was chosen as it is suited to detail research on the topic and identify research gaps in the existing literature through systematically searching, selecting and synthesising existing knowledge18,21.

Objectives

The framework provides an appropriate methodology to explore the role of community events in increasing the uptake of Indigenous-specific health assessments. This review aims to detail the current literature, identify research gaps in the existing literature, and inform the development of future health check programs. The following research question was devised to help guide the scoping review: How have community events been used to increase uptake of Indigenous-specific health assessments?

Search strategy

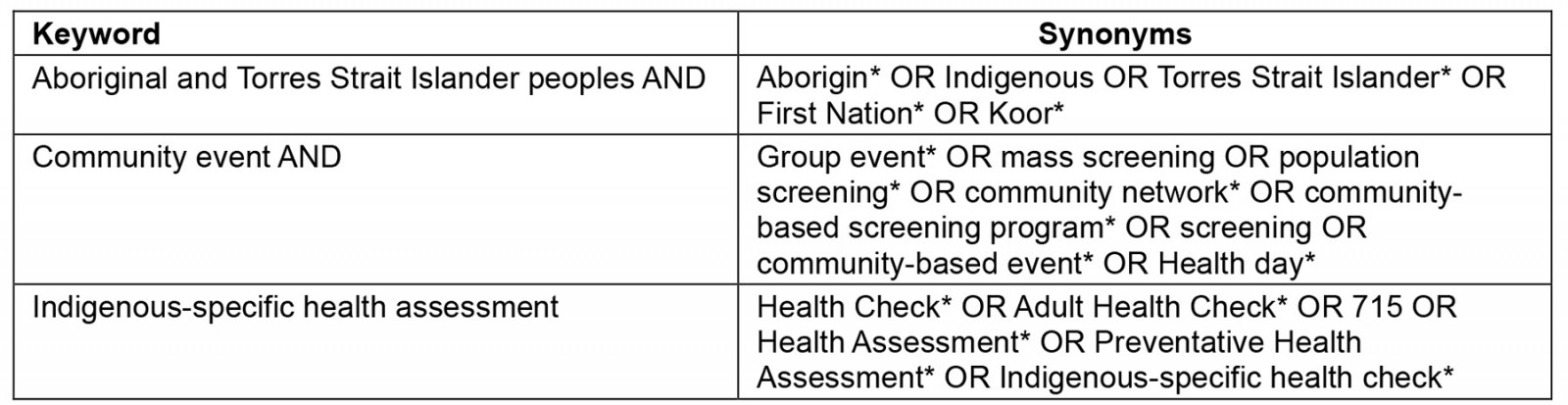

The search strategy aimed to locate published and unpublished (or grey) sources of evidence. A preliminary scan of two academic databases (Medline and Embase) was undertaken in March 2022 to identify relevant articles on the topic. The keywords and related subject headings were refined according to text contained in the title and abstract of the initial literature search (Table 1). Based on the keywords identified, a comprehensive search was conducted in five academic databases in March 2022 (Informit Indigenous Studies database, CINAHL via Ebsco, SCOPUS, Medline via OvidSP, Embase via OvidSP) and three sources of grey literature (Google/Google Scholar, Indigenous HealthInfoNet and Closing the Gap Clearinghouse). This initial search was then updated in April 2023, where no new data were found. Reference lists of included articles were screened for additional studies not found in the initial search. Search results were limited to the first 100 results when searching sources of grey literature.

Table 1: Scoping review search strategy

Eligibility criteria

Population: The search included articles from Australia specific to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples, and countries with colonised Indigenous Peoples such as Canada, New Zealand and the USA. The risk of generalising findings from larger population studies to specific Indigenous cultural groups or communities is ever present.

Concept: The review aimed to capture sources of evidence that pertain to programs that used a community event to promote the uptake of Indigenous-specific health assessments. It sought to explore how community events were thought to increase engagement in structured health assessments and improve health outcomes for Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander individuals and communities.

Context: The location of care for Health Check Days includes primary health care and community settings (eg schools, sporting events). Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples represent a diverse community geographically, and all geographical locations were captured and recorded in the data.

Source of evidence selection

All identified sources were collated and uploaded into Cochrane’s systematic review software Covidence (https://www.covidence.org) and duplicates were removed. Sources were reviewed over two rounds for selection. In the first round, titles and abstracts were screened against the eligibility criteria. In the second round, the full text of included articles was screened to determine if they met the eligibility criteria.

Extraction of results

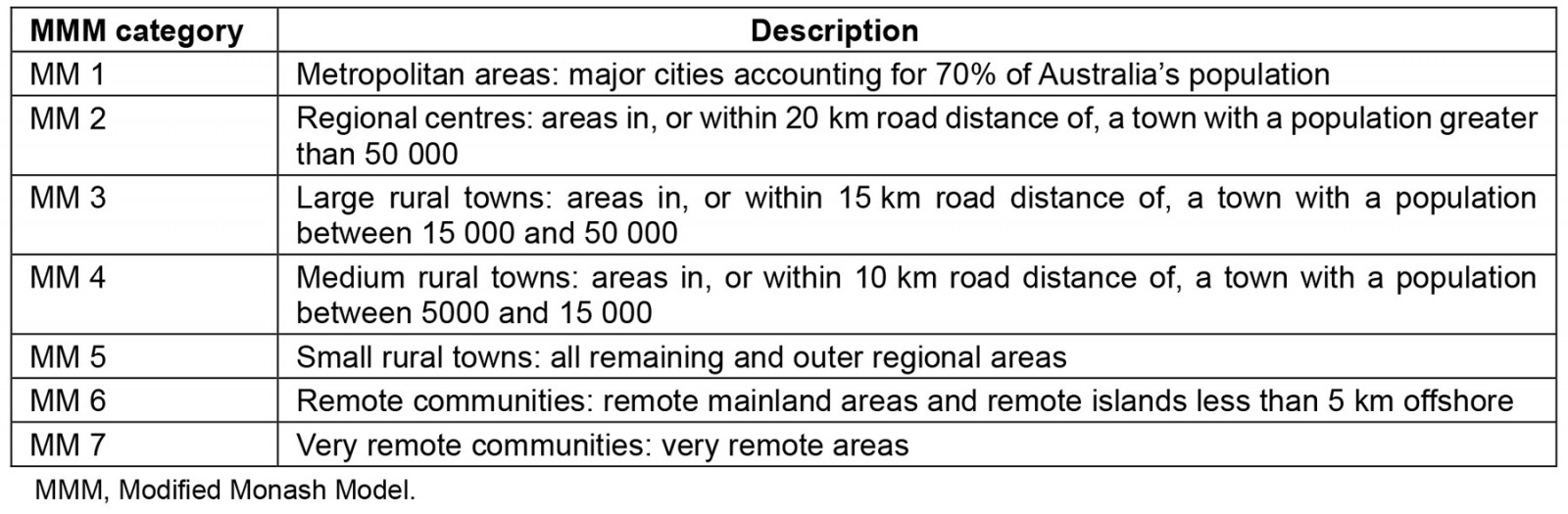

Data were extracted from the sources using the inbuilt data extraction tool from Covidence to obtain relevant study information. This included title, author, year, aim and design of source; program name, target population, target age and characteristics of program; and a summary of community engagement for community events. In accordance with the iterative methodology of the review, some changes were made to the data extraction tool during the review process. These changes included removing summary of community outreach due to high crossover with summary of community engagement; removing study aim, design and methods for grey literature sources; and adjusting setting to include geographical classification to improve the utility of the basic numerical analysis. The geographical classification of the program setting was determined using the Modified Monash Model (Table 2)22. The Modified Monash Model is how the Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care determines whether an area is considered regional, rural or remote. It tells us about an area according to geographical area and town size. This model was selected because, increasingly, remote classification reflects difficulty in finding medical help and that residents may find accessing doctors takes longer and is more expensive.

Table 2: The Modified Monash Model for classifying regional, rural and remote areas

Data analysis

To evaluate how community events have been used to increase uptake of 715 health checks, this review employed basic numerical analysis of geographical location, target populations, characteristics of each program, and extent of community engagement. The descriptive data were analysed by conventional content analysis to conduct a narrative synthesis23. Data extracted from the sources were organised thematically to summarise the main findings and address the research question. The combination of these analytical frameworks allowed for detail on the current research on the topic and identification of current research gaps in the literature.

Consultation

The consultation process was initiated through an overarching project related to implementing Health Check Days at two local Aboriginal Medical Services in the Northern Rivers region of New South Wales. One of the health services’ clinical directors invited the researchers to interview staff who were responsible for Aboriginal children’s 715 health checks. Using a semistructured interview approach, the researchers talked with two senior staff members. The aim of the interview was to inform the scope and method of the trial with the past experiences of the local community in the development and deployment of a previous Health Check Day. The results of the study will be fed back to this health service to inform the development of future Health Check Days, in terms of how best to use community engagement to increase the uptake of Indigenous-specific health assessments in this community.

Ethics approval

This original research had ethics approval under AHRMC – 1900/21: Provision of Aboriginal Health Check Days with a community engagement focus.

Results

Study selection

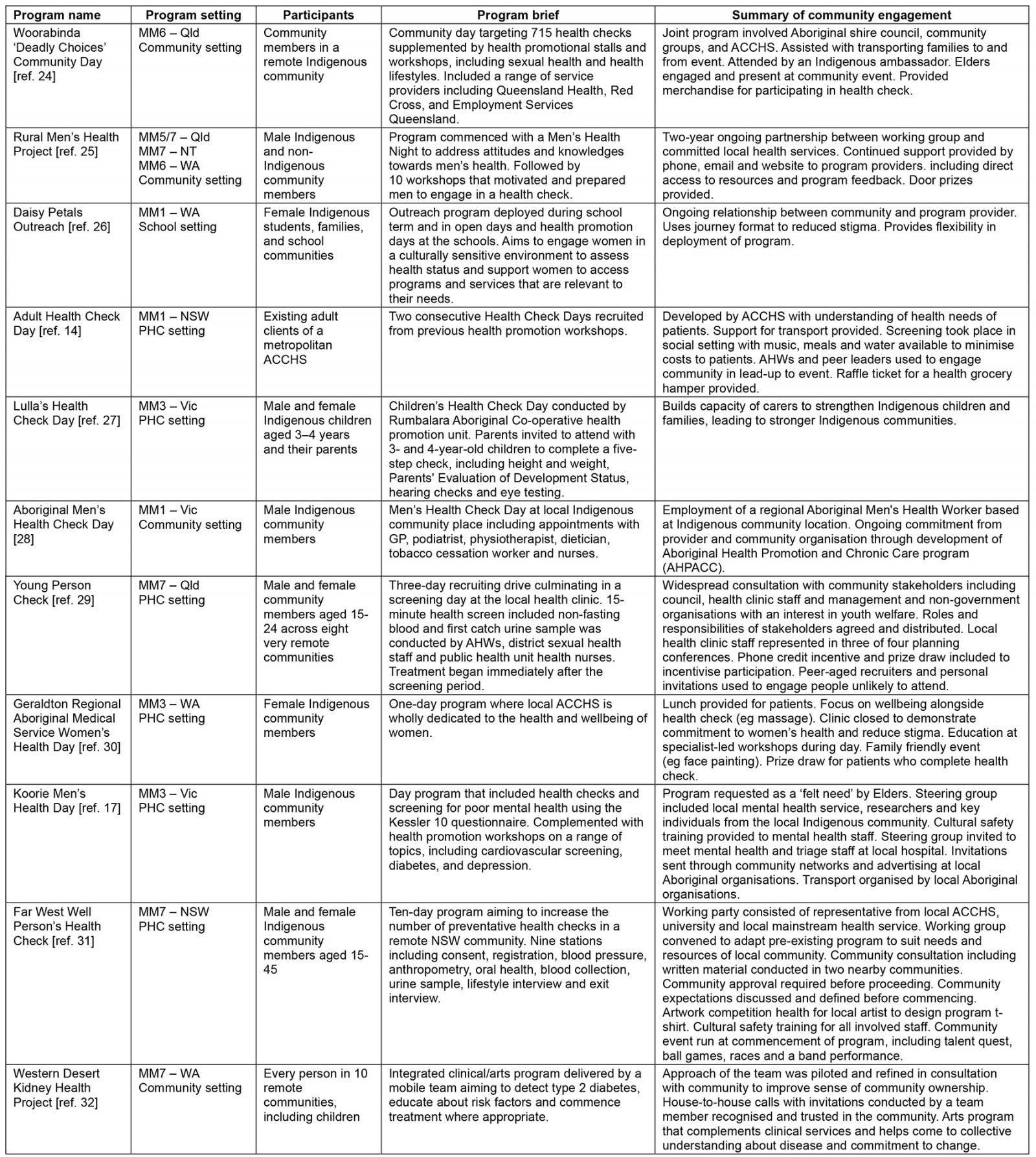

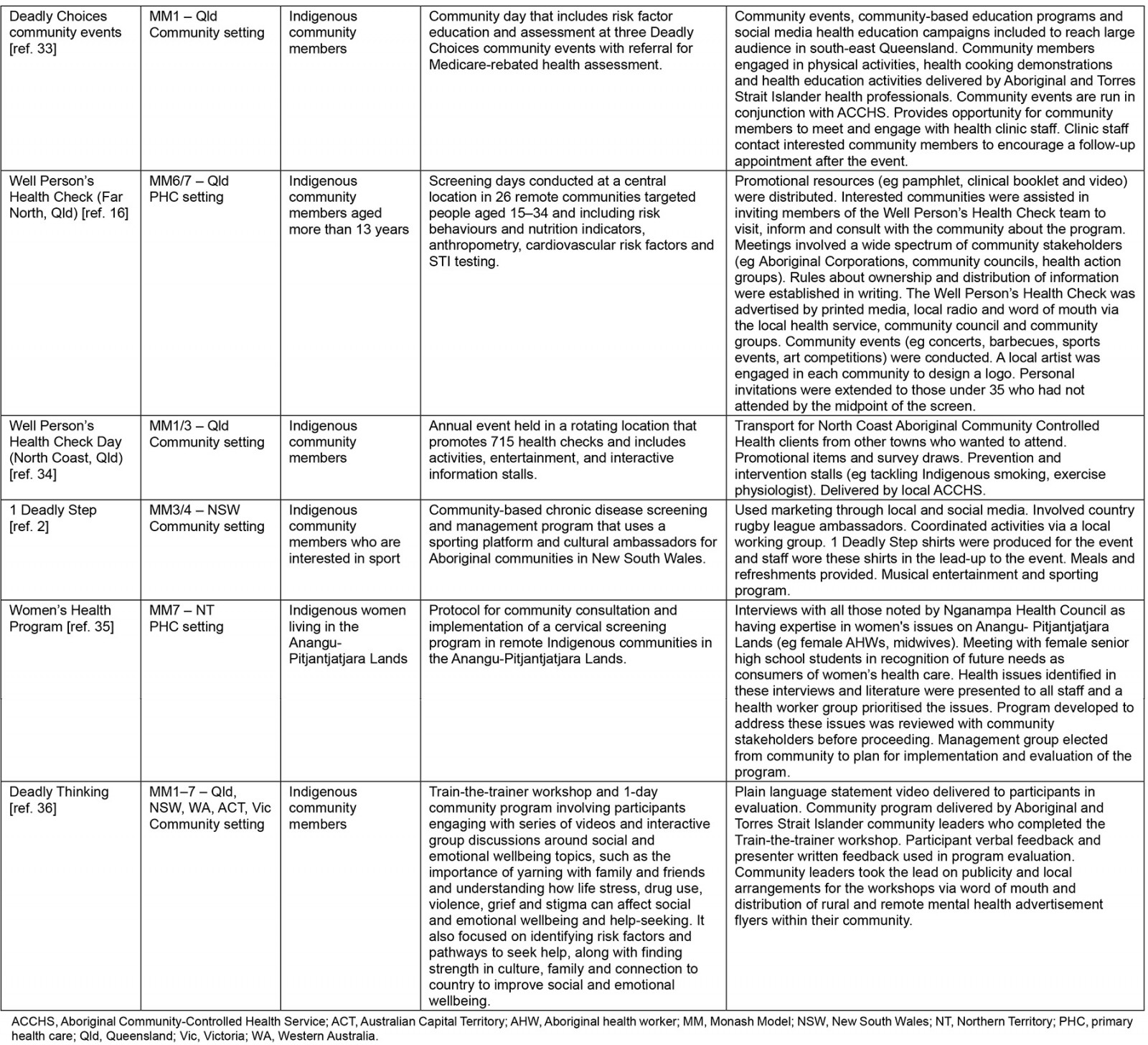

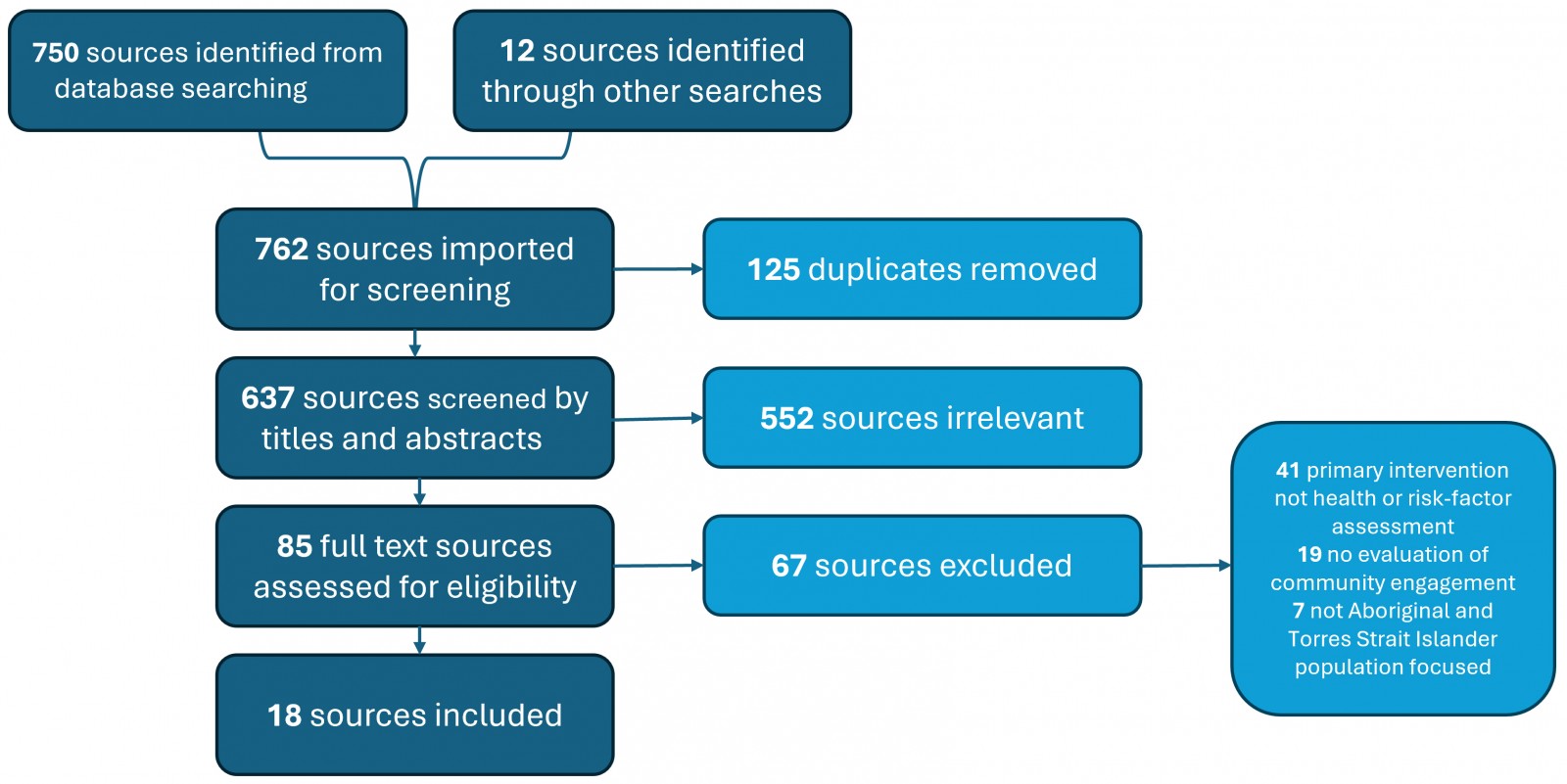

The search identified 762 sources of evidence from the eight databases and reference lists searched. A total of 125 duplicate articles were removed, and the remaining 637 studies were screened according to the eligibility criteria listed above. After a review of title and abstracts, 85 sources were included for the full-text review. Following the second round of review, 67 studies were excluded due to included programs not aligning with the eligibility criteria. The search strategy and study selection are visualised in Figure 1. In total, 18 sources were included in this scoping review, from which 17 unique programs were identified2,13,14,16,17,24-36. The details of identified programs are charted in Table 3.

Table 3: Details of the identified programs

Figure 1: Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram – systematic scoping review search strategy and study selection.

Figure 1: Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram – systematic scoping review search strategy and study selection.

Program characteristics

As a result of the first eligibility criteria, all programs included in the review were based in Australia. Four programs were based in a metropolitan areas (MM1)14,26,28,33, three were based in large rural towns (MM3)17,27,30, one was based in a remote community (MM6)24, and four were based in very remote communities (MM7)29,31,32,35. Five programs were delivered across a range of geographical classifications2,16,25,34,36. Programs were delivered across three key settings. Eight programs were delivered in a community setting2,24,25,28,32-34,36, eight in a primary healthcare (PHC) setting14,16,17,27,29-31,35 and one in a school setting26.

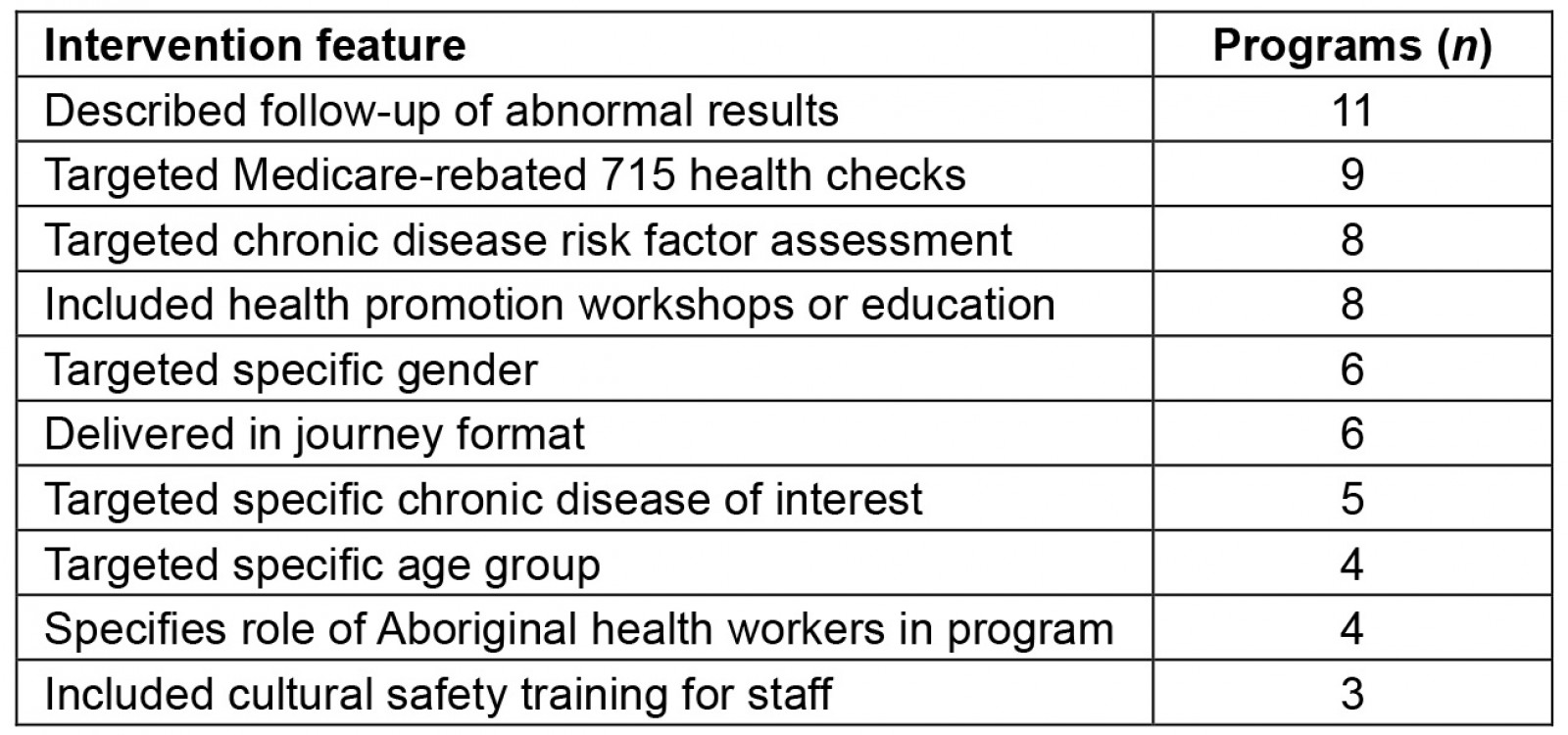

A range of delivery methods was employed. Nine interventions targeted delivery of 715 health checks14,16,24,25,28,30,31,33,34, eight programs used a risk factor assessment2,17,26,27,29,32,35,36, and eight programs supplemented 715 health checks with health promotion education workshops2,17,24,25,28,30,33,34. Six programs were delivered in a journey format14,16,26,28,31,34, and 11 programs described how they would follow up abnormal results, either with further diagnostic testing or with commencement of treatment2,17,24,25,28,29,31-34,36. Some programs were specifically directed at a group within the community. Six programs targeted a specific gender17,25,26,28,30,35, five targeted a specific chronic disease of interest to the community17,29,32,35,36,and four specified a target age group26,27,29,31. Some programs were explicit in how they prepared staff for program delivery. Four programs discussed the role of Aboriginal health workers (AHW) in the delivery of the program14,28,29,35, and three included cultural safety training for all staff in the lead-up to the event14,17,31. The breakdown of intervention features identified are described in Table 4.

Table 4: Breakdown of intervention features and number of programs

Community engagement characteristics

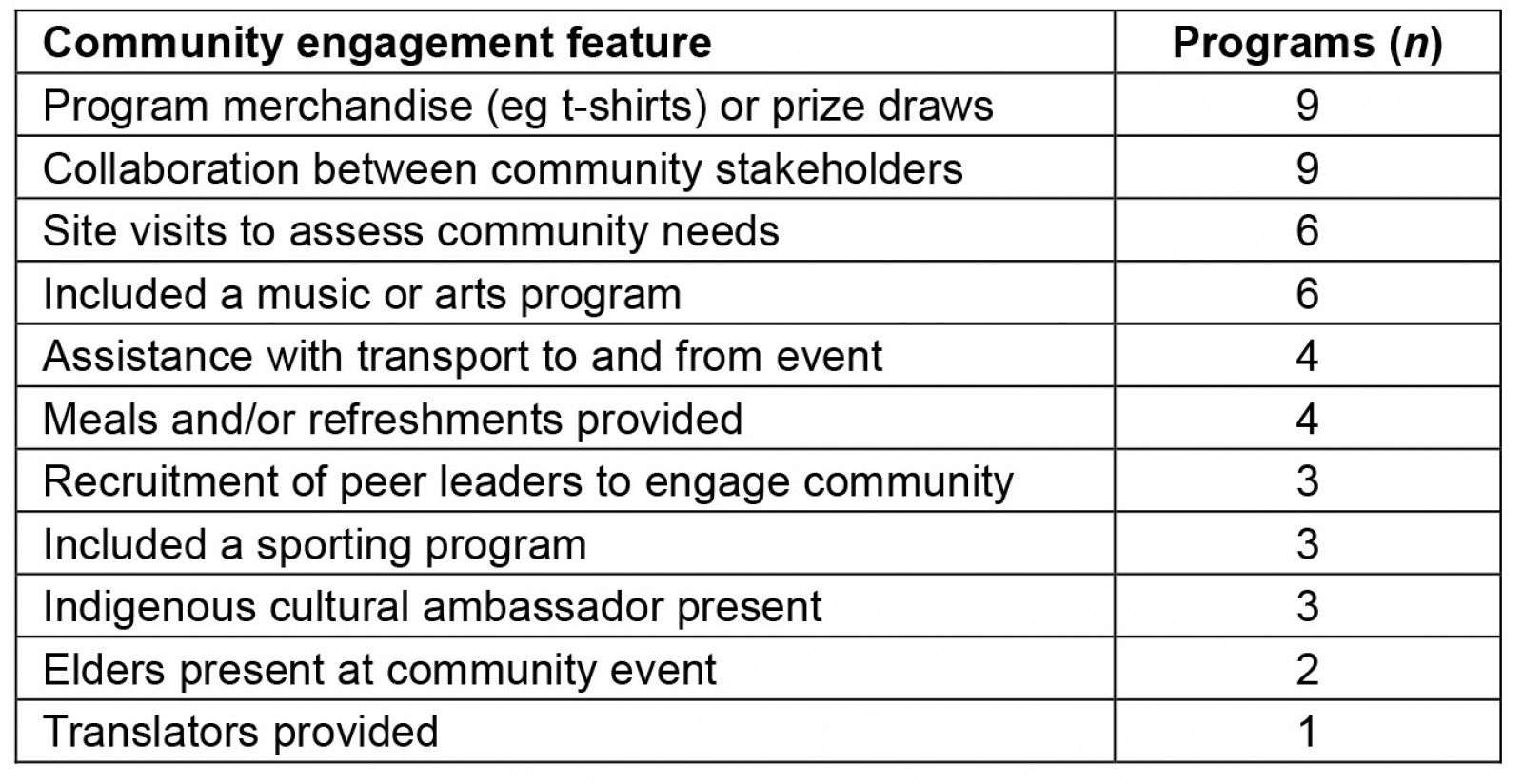

Programs used a range of methods to engage the community and increase participation in the programs. Nine programs incentivised participation by providing program merchandise or prize draws2,14,24,25,29-31,33,34, four programs provided assistance with transport to and from the event14,17,24,34, and four programs provided meals or refreshments to participants2,14,16,17. Several programs detailed how they matched the program to the needs of the community. Nine programs detailed collaboration between important stakeholders16,17,24,25,28,29,31,33,36 and six programs described visits to community to assess needs before commencing the program16,17,28,31,32,35. Programs employed a range of ambassadors to engage community in the lead-up to, or during, the program. Three programs recruited peer leaders to engage members of the community14,29,36, three programs invited cultural ambassadors to the event2,24,37, and two programs made an effort to engage Elders in the program17,24. Creating an event that appeals to the community was an important feature of some programs. Six programs included an arts or music program2,16,24,31-33 and three included a sporting program2,16,31 alongside the health-related activities. The breakdown of community engagement features identified is described in Table 5.

Table 5: Breakdown of community engagement features and number of programs

Findings from the narrative synthesis

Three themes relating to using community events to increase uptake of 715 health checks were identified through conventional content analysis: adapting the program to the community, providing a culturally safe participant experience, and prioritising community engagement.

Theme 1. Adapting the program to the community: A well-described community consultation process was emphasised in 11 of the programs16,17,24,25,28,29,31-33,35,36. Increasingly, programs are being led from inception to evaluation by Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services (ACCHS)14,26,30,31,34. This represents a valuable exercise in community control that enables programs to be designed and delivered to specifically address the health needs of the community. Participation in health check programs is greatest in programs where community input is significant and sustained16.

The development of a working party or steering group to match programs to community needs was described in several programs17,29,31,32,35. For example, the Far West Well Person’s Health Check utilised a working party with representatives from the local ACCHS, researchers from a local university, and local mainstream health services to adapt a pre-existing program to suit the needs of the community. A community consultation process was undertaken, with the findings from the working group and community approval being required to commence the project31.

Given the distribution of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities across a range of geographical settings, adapting the program to provide care in difficult circumstances with limited access to health care, the ‘tyranny of distance’, is important to program success. The five programs that took place in very remote communities (MM7) were required to be creative in their approach to promoting participation25,29,31,32,35. The Rural Men’s Health Project and the Far West Well Person’s Health Check employed teams to visit multiple communities within their catchment to overcome barriers to accessing a central location in the region25,31. The Young Person Check approached the issue with a 3-day recruiting drive to capture as much of the local community as possible, given the limitations in accessing regular screening in very remote locations29. The Western Desert Kidney Health Project provided specialist care to many remote communities by preparing a mobile clinic staffed by specialist medical providers to reduce demands on local space, equipment and expertise32.

Theme 2. Providing a culturally safe participant experience: Cultural safety can be defined as requiring health professionals and their associated healthcare organisations to engage in ongoing self-reflection to reduce bias and achieve equity, as defined by the patients and their communities38. Explicit strategies to provide a culturally safe patient experience were a feature of 10 programs and one qualitative study2,13,14,16,24,28,29,31,34,35. Interviews with ACCHS staff identified maintaining client-centredness and respecting varied priorities of participants as important in enabling uptake of 715 health checks in the PHC setting13. This includes targeting features of the program to address barriers to participation in screening; for example, space constraints, the need for confidentiality in tight-knit communities, time limitations of staff, skill mix and scope of practice, inability of clients to access screening days, and fears surrounding attending the day14.

There were many individual approaches to addressing these barriers across the programs identified. Some aimed to minimise costs to participants by providing transport to and from the event and covering meal costs for the day2,14,16,17,24,34. Others adapted the Health Check Day format to suit the needs and facilities of their community. Examples include engaging local Elders or well-known cultural ambassadors to promote the event and reduce fears around attending the program2,17,24,37.

Several programs underscored the importance of AHWs in promoting cultural safety and improving patient experience during the Health Check Day14,28,29,35. Fostering the development of AHWs with a specific 715 health check skill set and clearly defining their role in initiating and delivering 715 health checks was invaluable in delivering 715 health checks in the PHC setting13,14. The role of AHWs in supporting participants to access specialist health care, often with providers they have not met (eg diabetes specialist, program volunteer, visiting GP), is critical in overcoming barriers that people in rural and remote communities have in accessing medical care. The Aboriginal Men’s Health Check Day credits the employment of a regional Aboriginal men’s health worker as critical to the success of the program28.

Theme 3. Prioritising community engagement: Engaging the community is a critical feature of community events and their capacity to increase uptake of 715 health checks. Eight programs employed ambassadors to represent the program, including cultural ambassadors2,24,37, community Elders17,24 and peer leaders14,29,36. The delivery of the Koorie Men’s Health Day was closely tied to community Elders, being initiated by the Elders as a ‘felt need’ and being formally introduced by Elders on the program day17. The two Deadly Choices programs used celebrity sporting ambassadors to promote the event and share their stories with community on the day24,33. The Young Person Check used peer leaders to reach young people who may have not been engaged through traditional advertising, which was critical to improving participation in the program29. Nine programs provided program merchandise or prize draws to incentivise participation2,14,24,25,29-31,33,34. The use of custom shirts was described as critically important in enhancing event attendance2. Events based on the Well Person’s Health Check model ran a design competition to promote the event and engage local artists in the design of these shirts, promoting expression of culture and community engagement16,31.

Six programs engaged the community through providing a sporting, music or arts program2,16,24,31-33. The 1 Deadly Step program was held as a joint program with Country Rugby League of New South Wales and employed a sporting platform to promote the program, which was considered a useful community engagement strategy2. The Western Desert Kidney Health Project employed a novel approach of providing an integrated clinical/arts program to address the collective understanding of chronic disease in the community and promote commitment to introducing healthy habits32.

Discussion

Principal findings

This review identified 18 sources addressing how community events have been used to increase uptake of Indigenous-specific health assessments. The findings indicate that adapting the program to the community, providing a culturally safe participant experience and prioritising community engagement are frequently employed methods to increase uptake of 715 health checks. The most common program settings in the literature are the community and PHC setting.

An individualised approach to community events may be necessary for different kinship groups, communities and language groups39. The findings indicate that community control of the program through all stages of implementation is important in achieving this outcome. The ACCHS sector is recognised for its provision of holistic and comprehensive primary health care40,41 and may be best placed to have responsibility for the design and implementation of these programs. In cases where generalised programs are adapted for individual communities, such as the Well Person’s Health Check model16,31,34, these services are critical in ensuring the program is appropriate for the health needs of their community.

The findings indicated that a commitment to providing culturally safe health care is important in the success of community events, and several programs identified the importance of AHWs in the provision of culturally safe health care. AHWs take a holistic health approach, with a strong focus on respect, support and advocacy for their clients in their family and community context42. Qualitative approaches that utilise Indigenous interview styles have contributed to our understanding of how AHWs can be used to deliver community events, and further research into this style is warranted13,14,33.

The literature indicates that an authentic commitment to community engagement is required to increase uptake of 715 health checks. Cultural ambassadors must be able to speak passionately about the program and be present at the event2. Cultural programs that run alongside the event can be used to celebrate local artists, musicians and sportspeople. Novel approaches to integrated arts/clinical programs may present an opportunity to integrate culture and health care to promote sustained behavioural change in issues that have traditionally proven difficult to overcome32.

Geographical location is central to the allocation of healthcare resources in Australia. People who live in rural and remote areas continue to find it harder to get medical help, and access to doctors can take longer and cost more22. Programs that are based in rural and remote areas require novel approaches to overcome barriers to participation, including advertising and recruitment, travel cost and time and lack of skilled healthcare workers. Programs that take place in metropolitan settings are likely to be better resourced and represent an opportunity for significant reach, with more than a third (401 700) of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People living in the major cities of Australia43.

While not the purpose of this scoping study, a brief search of the international literature was completed on the Google Scholar database using the search terms Indigenous and (Canadian or American) and (Health Check) and (Event or Day or Group). This search aimed to identify other experiences for First Nations communities who have a historically similar colonial past to Australia. Reviewing the results uncovered one paper that discussed Indigenous people, screening and community events44. The program was specifically targeted at cervical screening program, a health priority area for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women in remote areas of Australia35. First Nations women living in Alberta, Canada, attended a discussion with researchers centred on strategies to increase uptake of cervical screening. In exploring the barriers and facilitators to uptake of cervical screening, the study found that participants wanted screening included with community health, health promotion and wellness events. They also suggested there may be benefit of building screening into women’s social groups and meetings. Specific to community events, the study found that ‘motivating with culturally appropriate community-based strategies’ was a meaningful way to increase participation in screening programs. This is not a conclusive piece of evidence but does acknowledge that other First Nations People and communities may also benefit from the use of community events to increase participation in Indigenous-specific health assessments.

Gaps in the literature

This study aimed to support the development of a program to deliver en masse 715 health checks in the setting of a community event. The most significant gaps in the current literature are that while many programs have been locally designed and delivered, few have provided the detail required to inform the development of future Health Check Day programs. There is limited information on how the events were designed, the logistics of running the event, and who needed to be involved from within the service responsible for delivery and from the wider community (eg local councils). Further, specific outcomes-based evaluation is limited throughout the literature. Information about whether the community events increased the number of 715 health checks at a given service, and evaluation from the perspective of the service and the patients, were only included in a minority of programs included in the study.

Only one paper focused on 715 health check events for children aged less than 13, confirming that there is a paucity of research on the delivery of 715 health checks in the school setting. School-based interventions align with the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2021–2031 priority area of Early Intervention45. There is a need for further research on the development and delivery of programs in this setting.

Limitations

Scoping reviews do not include risk of bias or other assessment of included studies, limiting the capacity of the review to provide concrete recommendations for policy and practice. In line with objectives of the review, this review points to research that needs to be conducted, rather than contributing essential primary research to the literature. While 18 papers were found, these were more of a narrative style and explanation than a study of efficacy; therefore, it is hard to draw conclusions on increasing numbers for 715 health checks. This review did not limit inclusion by year of publication so as to increase the reach of the search strategy. This meant that several older programs and references were included, which may not reflect the significant and ongoing evolution with regard to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander healthcare interventions.

Future directions

Future research will benefit from a renewed focus on evaluating 715 health check programs that utilise community events, in line with a move to establishing a principles-based framework for evaluations of programs affecting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples46. Establishment of a learning collective in which service representatives could share resources, determine optimal operational approaches, benchmark their performance, and develop data-driven strategies may strengthen the capacity of the ACCHS sector to deliver robust Health Check Day programs. This review aspires to contribute to a broader international body of literature on Indigenous-specific interventions across the aim to improve equity and access for all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations.

Conclusion

The aim of this scoping review was to explore how community events have been used to increase uptake of Indigenous-specific health assessments. This approach allowed us to identify the key characteristics of community events and characterise the key questions regarding how community engagement supports can increase uptake of 715 health checks. We expect this review will underpin a larger, more specific study on community engagement and 715 health checks. In the meantime, we hope this review serves as a conversation starter for health services and health promotion groups as they design, implement and evaluate 715 Health Check Days that are appropriate for the individuals, families and culture that make up their community.

Funding

No funding was received for this research.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.