Introduction

Rationale

Māori, the Indigenous Peoples of Aotearoa New Zealand, are disproportionately represented in cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevalence, morbidity and mortality rates, and are less likely to receive evidence-based CVD treatment1-3. Coronary heart disease (CHD) is one of the most significant contributors to inequities in life expectancy for Māori, compared to non-Māori, non-Pacific people4. These health disparities give rise to Māori experiencing a greater burden of disease and an enduring gap in life expectancy compared to non-Māori5-7.

Inequities in CVD outcomes and access to quality CVD health care in Aotearoa New Zealand are similar to those experienced by Indigenous Peoples globally, including nations impacted by colonisation. CVD disproportionately affects Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples in Australia; American Indians; Alaska Natives; First Nations, Métis and Inuit (FNMI); and Native Hawaiians, compared to other ethnic groups within their respective nations8-10. For example, CVD prevalence in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples is 1.5 times higher than in non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples, and the CVD mortality rate in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples is three times higher than that of non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples10. At the same time, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients are 40% less likely to receive evidence-based coronary interventions and have an in-hospital mortality rate double that of non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples 11. Similarly, Indigenous Peoples in the US have worse access to quality CVD-related health care and receive poorer CVD-related health care than White Americans12.

These patterns of health disparities experienced by Indigenous Peoples are mirrored globally due to the ongoing impacts of colonisation8,13,14. The historical trauma intergenerationally experienced by Indigenous Peoples through sustained dispossession of land, cultural oppression, persistent systemic racism and social deprivation adversely impact the opportunities for Indigenous Peoples to have good health and successful engagement with their respective healthcare systems8,11,14,15. The health impacts include significant physical, psychological and structural stressors, which inherently drive inequities in CVD risk factors and CVD outcomes16.

Inequities in CVD outcomes and healthcare access are contrary to the rights of Indigenous Peoples. In Aotearoa New Zealand, Māori rights to equitable health outcomes are derived from three key sources. First, Article 2 in the Te Tiriti o Waitangi (Treaty of Waitangi), the founding document of modern Aotearoa New Zealand, asserts the protection of Māori taonga (anything valued by Māori, including health) and Māori sovereignty over those taonga17,18. Second is the Pae Ora (Healthy Futures) Act 2022, which repealed and replaced the New Zealand Public Health and Disability Act 2000. Health sector principles within the Pae Ora (Healthy Futures) Act 2022 state that the health sector should be equitable for Māori, including equitable access to services, equitable levels of services and achieving equitable health outcomes for Māori19. Third, the New Zealand Ministry of Health recently updated its expression of the Crown’s Te Tiriti o Waitangi obligations in the New Zealand health and disability system by publishing a new Te Tiriti o Waitangi Framework. The framework includes mana tangata, which expresses the Crown’s commitment to achieving equity in health and disability outcomes for Māori20. These rights to equitable health outcomes extend to international Indigenous Peoples, as stipulated in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples 200721.

The Pae Ora (Healthy Futures) Act 2022 also commits to improving health outcomes for rural communities and a targeted national Rural Health Strategy19. Rurality in Aotearoa New Zealand is defined by the Geographical Classification of Health22. Rural Māori, under this classification, experience additional barriers to treatment access and poorer health outcomes than those living in urban areas7,23. Rural Māori also experience higher all-cause and amenable mortality rates, compared to rural non-Māori and urban Māori7. Evidence shows that rural Māori have a more significant burden of CVD risk factors, ischaemic heart disease, heart failure and stroke mortality (≥35 years) compared to urban Māori or urban non-Māori4,24. Inadequate funding, accountability and access to primary care services for rural Māori has also been documented25. Gaining a stronger understanding of the barriers and facilitators that influence access to CVD care is critical to addressing inequities in access to care and health outcomes in rural Māori.

To our knowledge, no known organised review of evidence that explores the barriers and facilitators to accessing CVD health care among rural Māori has been undertaken. A scoping review was conducted to identify the extent to which literature on this issue is available, identify any gaps in the literature and map available evidence 26. Given the scarcity of local literature and the similarities in health disparities experienced by Indigenous Peoples in colonised nations, we extended this review to include rural Indigenous Peoples in other colonised nations27,28.

Objectives

This scoping review aimed to identify and describe the extent of research investigating the barriers and facilitators associated with accessing CVD healthcare for rural Indigenous Peoples. Specific objectives were to:

- identify the extent of research available

- map and summarise main findings related to the barriers and facilitators to accessing CVD health care in Māori and other rural Indigenous Peoples

- identify and describe any gaps in the literature

- identify and describe how further research in this area can benefit rural Māori and other Indigenous Peoples' CVD healthcare access.

Methods

The conduct of this scoping review followed Arksey and O’Malley’s Scoping Review Methodological Framework29 and was underpinned by kaupapa Māori research methodology (KMR)29,30. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines were also followed31. This review was led by an emerging Māori health researcher (TT) and was supported by a well-established Māori health researcher (MH) and accomplished tauiwi (non-Indigenous) health researchers (KE, VS) who have significant experience in Māori health equity research. The full study protocol for this scoping review has been published elsewhere32. A summary of the methods used is provided below.

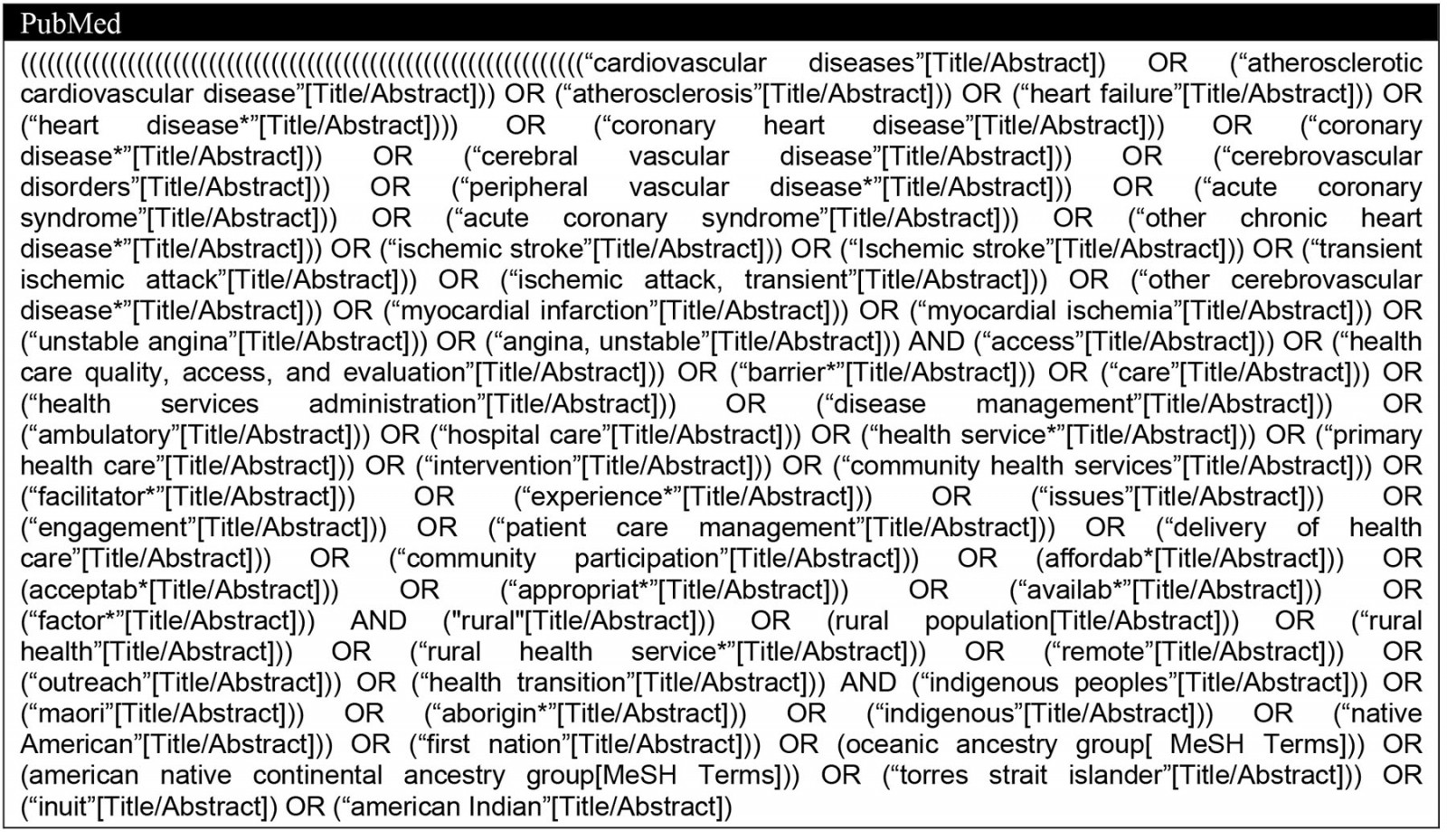

Search strategy

Literature was identified from eight databases (MEDLINE (OVID), PubMed, Embase, Scopus, CINAHL Plus, Australia/New Zealand Reference Centre, NZResearch.org) and a grey literature search of government websites from the countries included in the scoping review (New Zealand, Australia, Canada, US), the WHO website, and the Google search engine (limited to first 30 results). The search strategy used in the PubMed database is included in Appendix I. The literature search was conducted between March and June 2022. Articles were managed using EndNote software and NVivo v1.7.1 (Lumivero; https://lumivero.com/products/nvivo).

Eligibility criteria

Articles were considered for this scoping review if they met all of the following criteria:

- discussed Indigenous Peoples from Aotearoa New Zealand, Australia, US and Canada

- included CVD conditions such as atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, coronary heart disease, acute coronary syndrome, myocardial infarction, unstable angina, cerebral vascular disease, ischaemic stroke, transient ischaemic attack, peripheral vascular disease and heart failure

- used the terms ‘rural’ or ‘remote’ when referring to the geographic distribution of their population of interest

- had any care-based setting (including community, inpatient and outpatient)

- reported barriers or facilitators to accessing CVD care from the perspectives of Indigenous Peoples or health service providers

- were published between January 1991 and January 2022

- were reported in any language.

Data screening and charting

The lead author conducted the search. Two reviewers independently screened abstracts and titles for database articles, followed by full-text articles. The lead author searched for grey literature and screened full texts. A second reviewer then independently reviewed the full text of the grey literature reports. Any disagreements throughout the screening process were resolved via discussion between the two reviewers and an additional research team member, who mediated the discussion until consensus was reached. The data for the finalised literature list was then extracted and charted using Microsoft Excel. The lead author then charted the following study details: author, article title, year, country, study type, study aims, study design, inclusion/exclusion criteria, participant characteristics, recruitment procedures, sample size, reported barriers, reported facilitators, and gaps or limitations.

Search strategy results

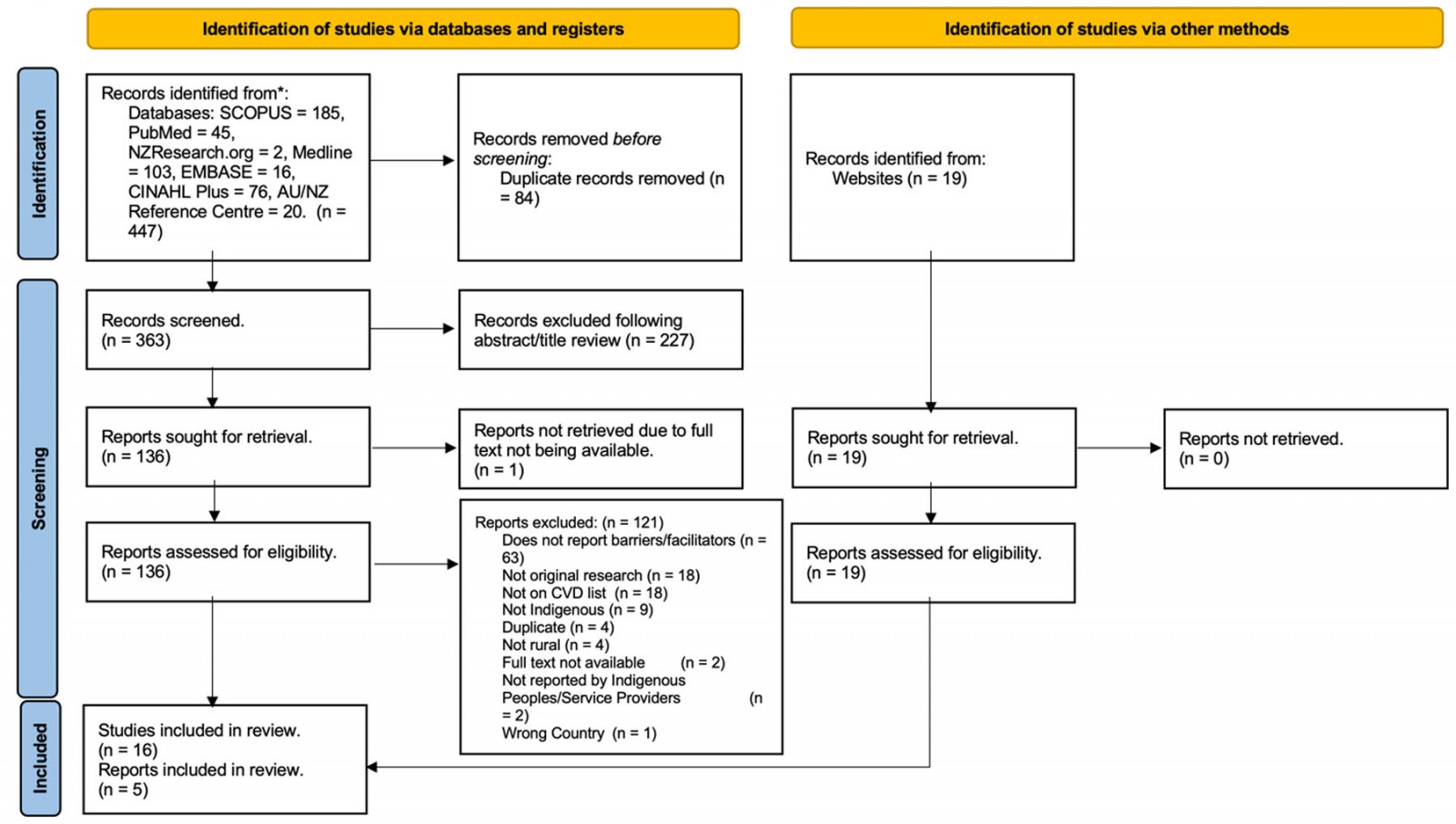

The search strategy results are shown in the PRISMA flow diagram (Fig1). A total of 447 articles were identified in the database search and 19 articles were identified from the grey literature search. Following screening, 21 articles (16 database articles, 5 grey literature articles) were included in the review.

Figure 1: PRISMA flow diagram of search strategy results.

Figure 1: PRISMA flow diagram of search strategy results.

Critical appraisal

While critical appraisal is not generally undertaken as part of a scoping review29, the lead author conducted two critical appraisals of the included literature to strengthen the conduct of the review.

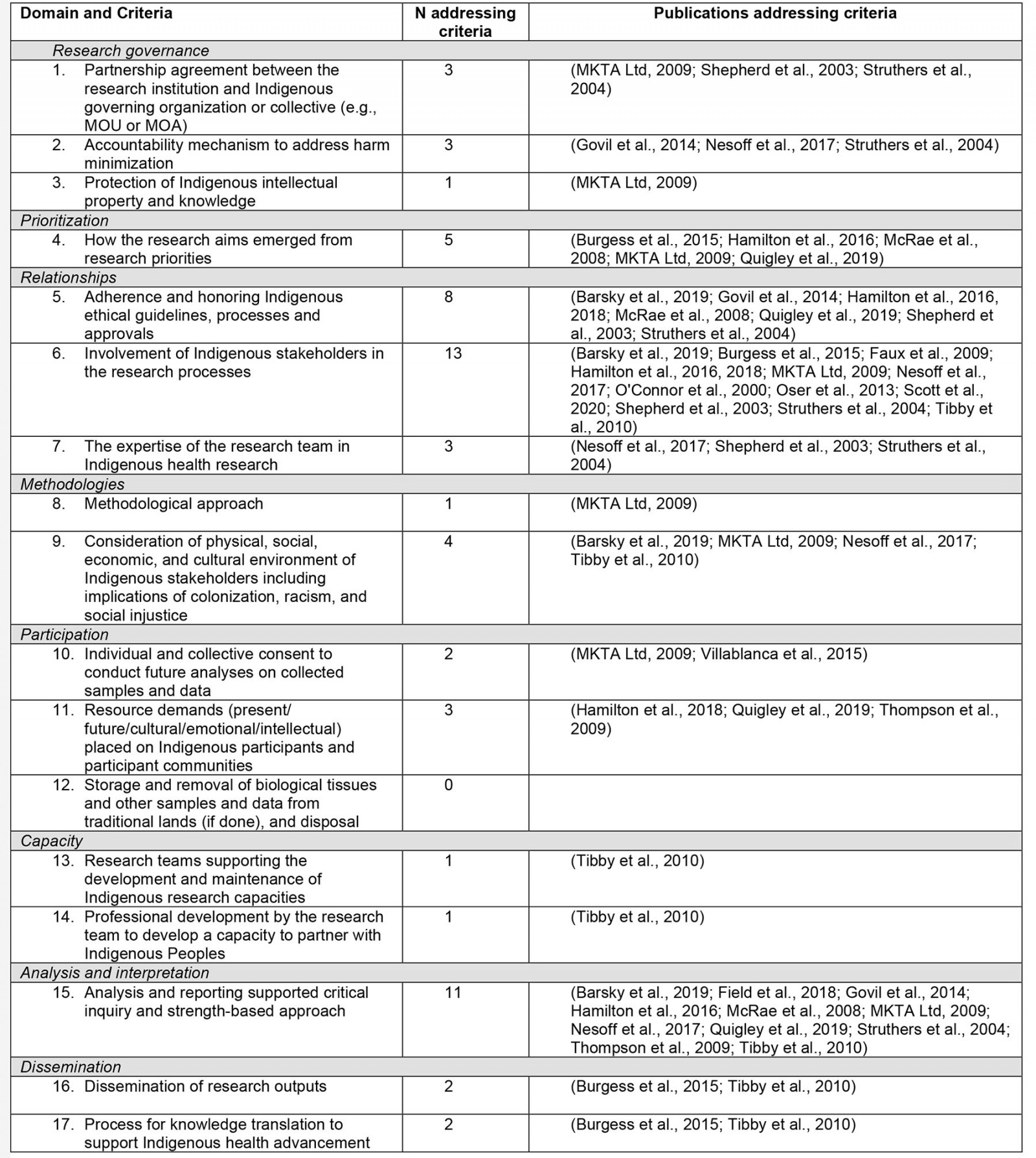

CONSIDER statement: All 21 included articles were reviewed using the consolidated criteria for strengthening the reporting of health research involving Indigenous Peoples (CONSIDER statement)33. The CONSIDER statement appraisal was conducted to assess how the literature addresses health inequities and approaches to Indigenous health research33. Although the information from this appraisal was not used in the data synthesis, evaluating the literature from an Indigenous perspective was essential to identify where Indigenous health research conduct may be strengthened. Most articles (n=19) addressed at least one or more of the CONSIDER statement criteria. However, none of the articles addressed all CONSIDER statement criteria, and two grey literature articles34,35 did not address any criteria. A summary of the CONSIDER statement findings is provided in Appendix II.

AACODS checklist: The second appraisal sought to critically evaluate the five grey literature articles for inclusion in the scoping review using authority, accuracy, coverage, objectivity, date and significance (AACODS checklist)36. The AACODS checklist is a tool used for grey literature to assess the rigour and trustworthiness of grey literature articles by evaluating the reputability of the organisation publishing the article (authority), the accuracy of the article level of peer review (accuracy), the limits or parameters of the article (coverage), level of objectivity and balance (objectivity) if the date that the article was written is provided (date), and how relevant the article is to the research area (significance). Of the five grey literature articles assessed, two did not indicate if they were peer-reviewed and did not satisfy the criteria for accuracy. All other criteria were satisfied. Therefore, all included grey literature articles were retained in the final synthesis.

Data synthesis

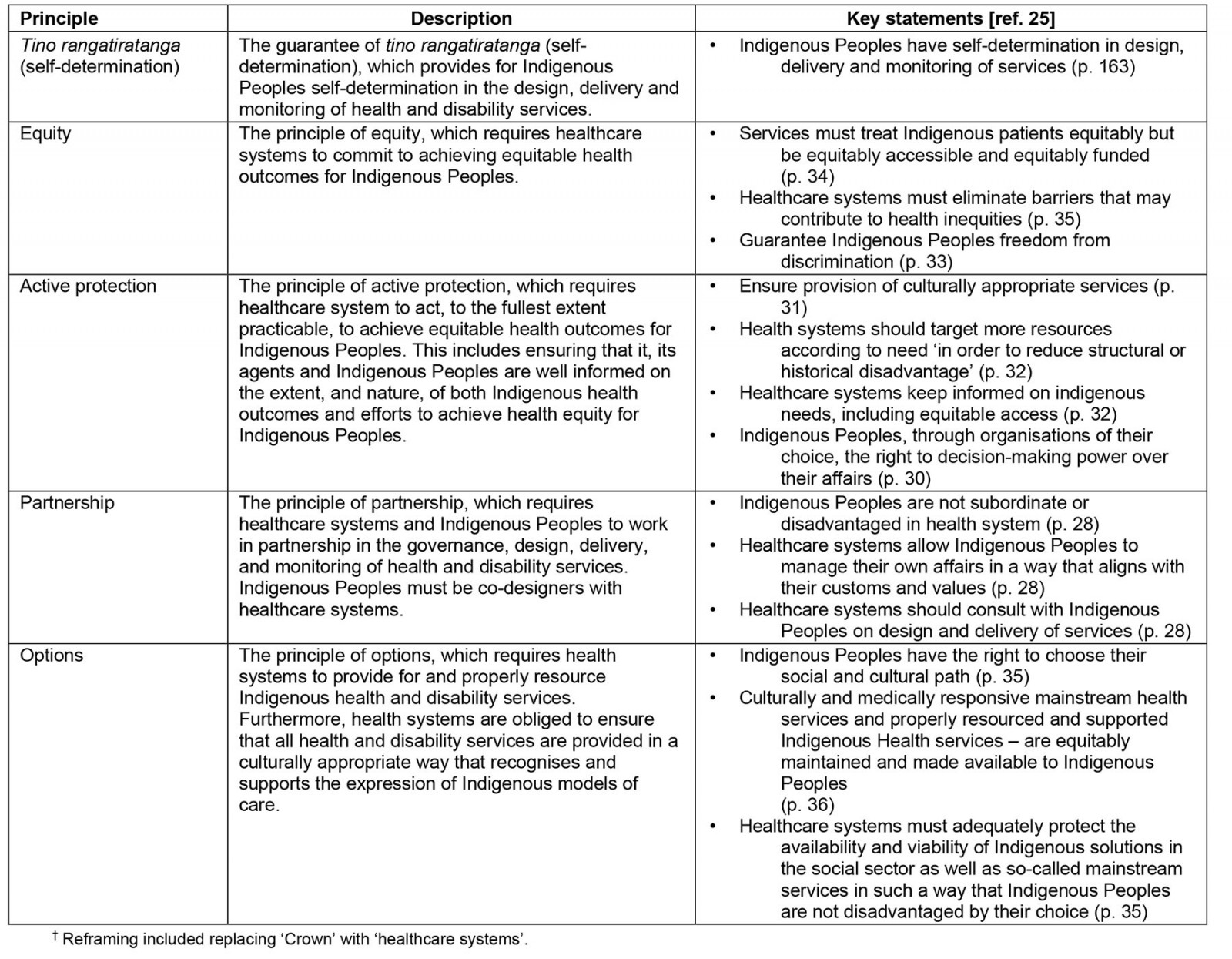

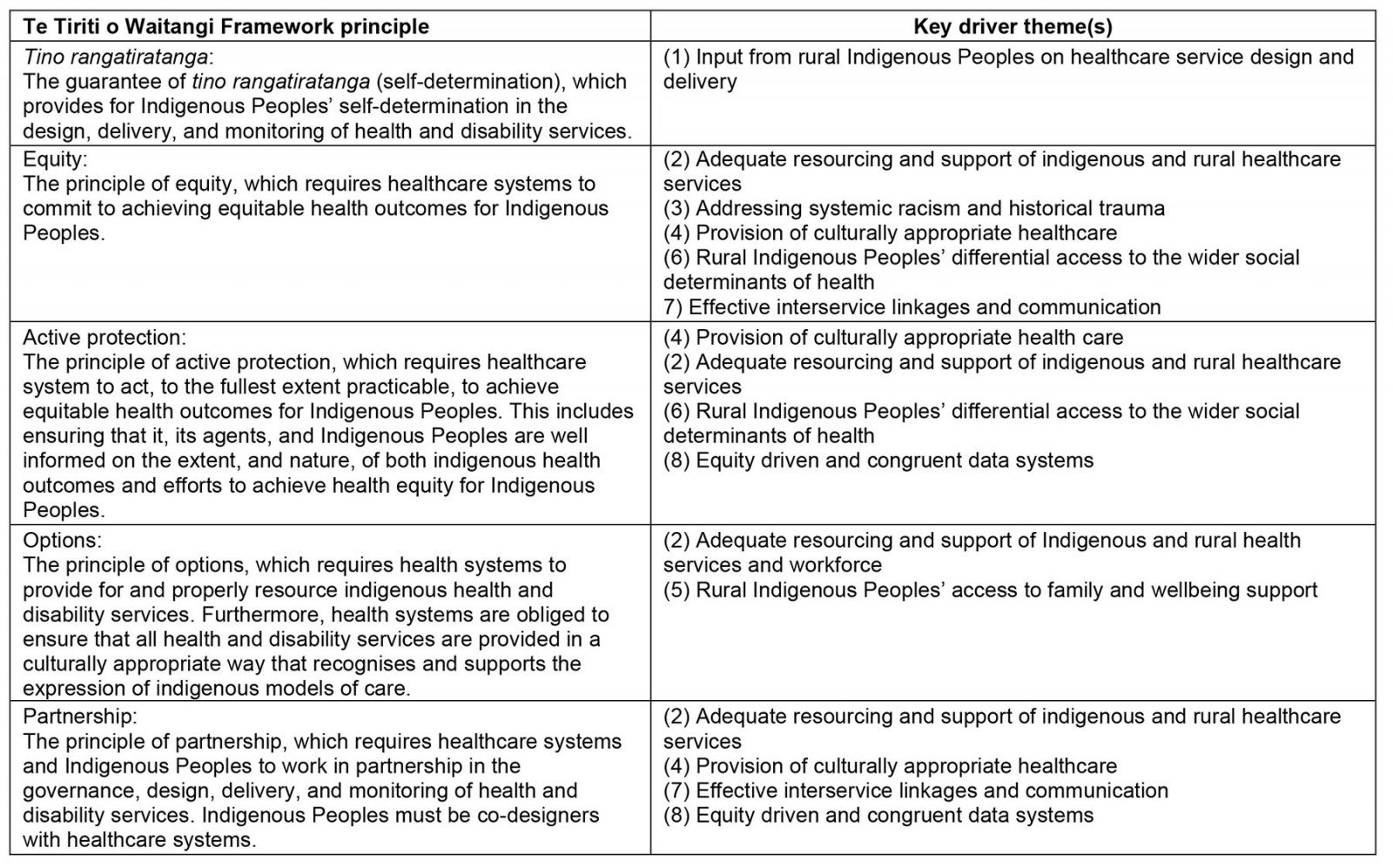

Findings from articles included in the final synthesis were initially double-coded and then thematically categorised by the lead author using NVivo software. All research team members then reviewed codes and preliminary themes, which were refined iteratively until a consensus was reached with all research team members. Finalised themes were then categorised using the New Zealand Ministry of Health Te Tiriti o Waitangi Framework principles20,25. These principles were first articulated by the Waitangi Tribunal in the Hauora report25 and describe the commitments of the New Zealand health and disability system to meet obligations to Māori under Te Tiriti o Waitangi25. In this scoping review, the language used to describe the Te Tiriti o Waitangi principles was reframed to support applicability in an international healthcare system context. Reframing included replacing ‘Crown’ with ‘healthcare systems’. Reframing was conducted with careful consideration of the statements within the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples21. The Te Tiriti o Waitangi Framework principles are summarised in Table 1. Key statements from the Hauora report25 relevant to each principle are also included to provide context.

Table 1: Reframed Te Tiriti o Waitangi Framework principles†

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was not sought for this review because publicly available data were used.

Results

A total of 21 articles (16 database articles, 5 grey literature articles) were included in the data synthesis. A summary of the main study characteristics and themes addressed in each article is provided in Appendix III. The majority of articles were from Australia (61%) and the US (29%), followed by Canada (5%) and Aotearoa New Zealand (5%). Most of the articles focused on CVD-related services or programs (81%) but also included health conditions such as chronic heart disease (10%), myocardial infarction (5%) and stroke (14%). Study designs included case studies (39%), mixed methods (24%), qualitative studies (14%), surveys (14%), integrative review (5%), and one article (5%) did not include a study design. Indigenous Peoples included Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples (61%), Native American or Alaska Natives (29%), First Nations Peoples in Canada (5%) and Māori (5%). Eight (38%) articles were published between 2000 and 2010 and 13 (62%) were published from 2011 onwards.

Synthesis of results

Findings were mapped into eight thematic categories, described as key drivers to CVD care access for rural Indigenous Peoples: (1) input from rural Indigenous Peoples on healthcare service design and delivery, (2) adequate resourcing and support of indigenous and rural healthcare services, (3) addressing systemic racism and historical trauma, (4) providing culturally appropriate health care; (5) rural Indigenous Peoples’ access to family and wellbeing support, (6) rural Indigenous Peoples’ differential access to the wider social determinants of health, (7) effective interservice linkages and communication, and (8) equity-driven and congruent data systems. Each key driver theme was categorised using the Te Tiriti o Waitangi Framework principles. Finally, a preliminary model was developed to assist in conceptualising the key themes elucidated from the literature in relationship with Te Tiriti o Waitangi principles (Table 2).

1. Input from rural Indigenous Peoples on healthcare service design and delivery: Five articles explored Indigenous community input on health service design and delivery. One study by Thompson et al showed a lack of Indigenous community input in their investigation of practitioner awareness and implementation of Indigenous health guidelines in Western Australia37. Thompson et al reported that only a minority (8.8%) of their study cohort (n=24) reported Indigenous community input into cardiac rehabilitation service design and delivery37. Four articles found that community consultation, particularly for community-based CVD interventions, was crucial for successfully implementing services in rural Indigenous communities38-40. One service provider reported adding or removing services to suit the health and social needs of its community and even participating alongside patients in sporting events as a collaborative approach to more effectively meet their health needs41.

2. Adequate resourcing and support of Indigenous and rural healthcare services: Seventeen articles examined resourcing, infrastructure and support of Indigenous and rural healthcare services and workforce. Articles reported that Indigenous healthcare services and workers are essential to building trusting relationships with rural Indigenous communities42-44, can effectively collaborate and communicate health needs to both providers and Indigenous communities37,44,45, provide culturally safe care37,46 and address barriers to care access by providing transport or homecare options to their communities41,46. For example, Field et al identified Indigenous health workers as an ‘essential part of the health service team, which needs strong relationships and trust within the team and program participants’ (p. 7)42. Similarly, MKTA Ltd reported that all Māori health providers included in its study emphasised the ‘importance of building trusting relationships with patients and their whānau’, which was seen as key to providing ‘effective care’ (p. 61)41.

Articles also reported that localised and Indigenous programs or services resulted in better communication between patients and their healthcare providers47, reduced waiting times48, increased service engagement49 or more effective collaboration between Indigenous health workers and pharmacists47. McRae et al described relationships between the pharmacists and Aboriginal Health Workers as a ‘key contributor to all suggested future strategies’ (p. 12) regarding the delivery of heart health care to Indigenous communities47. Articles also identified a preference for Indigenous healthcare services and workers in providing CVD interventions such as cardiac rehabilitation, by both communities and providers41,43,45. Govil et al43 found that Aboriginal patients living with CHD preferred Aboriginal Medical Services for their healthcare management, citing ‘greater trust in the AMS staff, the availability of multiple services, confidence in staff expertise and proximity to home and family support’ (p. 268)43. Four articles identified limited capacity and infrastructure within Indigenous healthcare services and the Indigenous health care workforce37,42,43,45.

Limited capacity and infrastructure were identified as barriers to mainstream rural healthcare service delivery. Articles described limited CVD specialist support in rural communities39,50,51, and a lack of necessary facilities or equipment to deliver quality in-service CVD health care or home-based care37,39,44. For example, Burgess et al stated that primary healthcare clinics in the remote Northern Territory in Australia have intermittent medical officer support, potentially contributing to delays in initiation and management of CVD medications50. Faux et al also articulated these challenges, stating that an occupational therapist may need to ‘charter a plane to visit the home of a remote patient to assess it for adaptations’ and that ‘once the equipment is ordered it may take weeks to arrive’ (p. 6)39.

Articles reported poor implementation of staff training due to organisational issues, complex training materials, or time constraints leading to the exclusion of learning topics43,50. For example, McRae et al described difficulties scheduling training sessions between Indigenous health workers and pharmacists, due to competing work priorities47. Articles also described adequate resourcing of rural health services as necessary to enable specialist healthcare professionals to more frequently support rural Indigenous communities, retain rural healthcare staff or move healthcare models from acute care to prevention and management39,41,50. Telehealth/telemedicine, mobile and home-based care options were reported as important facilitators to healthcare access, as they supported Indigenous people to be more informed and better engaged with their condition management, or led to reductions in travelling and waiting times to receive treatments39-41,44,46,48,49. The study by Tibby et al exemplifies this, with a reported 98% attendance rate and high patient satisfaction for their mobile specialist cardiac Indigenous outreach service based in rural and remote Queensland, Australia40.

Articles also identified a lack of funding support for Indigenous or rural healthcare services or programs40,41,52. Other resource-related barriers reported include rural healthcare workforce shortages37,39,41,44, long waiting times to access services39,43,53, the large and remote geographic areas rural services have to cover37,44,51, a lack of resourcing for the training of healthcare workers and Indigenous health workers in CVD healthcare provision45,47,51 and a lack of awareness of the roles of Indigenous health services and workers by mainstream healthcare providers44. Other articles highlighted effective training and development as an essential support mechanism to ensure the Indigenous healthcare workforce can confidently provide CVD health care to rural Indigenous communities41,43,47,51. Resourcing for training opportunities was described by Quigley et al as important for Indigenous health workers to gain the necessary knowledge and skills to talk to their community about stroke51. Articles also reported the necessity of ongoing, inservice CVD healthcare training or professional development, which also builds mainstream healthcare workers' confidence in supporting rural Indigenous communities with their heart health, or reduces staff turnover rates41,45,49. Barksy et al found that of the community health workers who participated in their study ‘almost all either agreed or strongly agreed’ that their CVD program training was ‘helpful and equipped them confidence in their ability to perform their role’ (p. 5)49.

Articles noted the importance of multidisciplinary healthcare provision and training, and that flexibility in roles that develop interprofessional networks allows a more holistic approach to care, or broadens care provision to include the social determinants that can influence health outcomes41,42,47. Multidisciplinary teams were also reported as important to supporting Indigenous healthcare workers, understanding Indigenous health needs, coordinating care or strengthening professional relationships within healthcare teams38,41,42,47. For example, McRae et al found that, following completion of their study, some pharmacists were motivated to build ‘sustainable, effective relationships with their aboriginal health workers’ (p. 11)47. When discussing strategies for the future, five pharmacists recommended multidisciplinary attendance at future education sessions to develop interprofessional networks47.

3. Addressing systemic racism and historical trauma: Three articles explored the influence of systemic racism and historical trauma in rural Indigenous Peoples accessing CVD health care. Two articles described experiences of Indigenous Peoples avoiding engagement with healthcare services due to feelings of shame and judgement by healthcare workers43,44. One article also explored historical trauma as a reason for refusal to seek healthcare treatment. Nesoff et al reported that Indigenous Peoples normalise ‘bad health’ and refuse to seek treatment due to historical trauma, with one participant commenting that ‘a lot of people feel that this is their destiny to have bad health just because their ancestors have experienced that’ (p. 134)44. Field et al42 also comments on the inequities in power distribution between Indigenous Peoples and healthcare services in a way that resembles ‘colonialism’ (p. 7)42, when referring to ineffectiveness in recording accurate medical histories. Trust and respect were reported as essential facilitators for strengthening relationships between Indigenous Peoples and healthcare professionals42.

4. Providing culturally appropriate health care: Sixteen articles explored barriers and facilitators relating to the provision of culturally appropriate health care for rural Indigenous Peoples. Articles reported barriers to accessing culturally appropriate health care, including a lack of cultural competence in healthcare services37, poor cultural training of staff51, poor understanding of Indigenous cultural needs in healthcare environments39,51 and poor provision of culturally appropriate care42,46. For example, one participant in the study by Quigley et al51 said ‘things like putting [people in] shared [mixed gender] wards shouldn’t happen in a facility in a regional place like this ... It does happen and it impacts on their [patient] well-being’ (p. 4)51. Articles also reported a lack of access to Indigenous language translation services39,44,51 and culturally appropriate resources52. This is important because, as Field et al notes42, meeting the cultural needs of Indigenous patients creates strong links between the patient and their healthcare provider.

Articles also described how Indigenous healthcare services and workers can effectively meet cultural needs while delivering care to Indigenous communities37,41,45,46. Cultural training of the general staff population was described as necessary for meeting Indigenous cultural needs and understanding Indigenous health needs41,42,46,47,54. As one pharmacist in the study by McRae et al describes, ‘the cultural awareness training got me to thinking more from the point of view of how the Indigenous [people] would be thinking … I have always had a wonderful interest, but it didn’t go very deep …’ (p. 10)47. Indigenous healthcare workers were reported as playing a pivotal part in mentoring general population staff in the training process37. Poor uptake of healthcare services or programs (eg cardiac rehabilitation) by rural Indigenous Peoples was also reported, alongside a failure by healthcare services to acknowledge reasons for the low uptake of these programs37,45. One article noted a preference by rural Indigenous communities for traditional healing rather than mainstream services, only resorting to medical services when traditional healing methods failed44.

Accessing culturally tailored, localised or positively framed educational materials was described by articles as vital to supporting rural Indigenous communities in successfully building knowledge of their conditions37,40,41,43,47,50,52,55,56. For example, Villablanca et al found that, following a targeted educational program, American Indian women ‘achieved the greatest gains in knowledge and awareness after the educational intervention’ compared to other ethnic groups included in the study56.

Some articles noted a lack of localised and Indigenous-specific education materials in rural Indigenous communities, leading to deficits in knowledge and awareness of their CVD condition, and poor health system navigation46,52,56. O’Connor et al noted that the lack of localised education materials was due to inadequate funding to produce localised materials52. Two articles reported poor uptake and compliance with Indigenous healthcare guidelines by health service providers46,54. In Hamilton et al’s study on the utilisation of cardiac rehabilitation by Indigenous Peoples in Western Australia46, the investigators found that, of the 38 cardiac rehabilitation coordinators interviewed in their study, none reported using the NHMRC’s Strengthening cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples: a guide for health professionals, despite the guidelines being recommended for use by all health professionals involved in the care of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples57.

5. Rural Indigenous Peoples’ access to family and wellbeing support: Ten articles addressed factors relating to access to family and wellbeing support in the healthcare journey. Seven articles reported a lack of access to family support as a barrier to accessing CVD health care. Barriers relating to family access included being away from family for some time due to the distance needed to travel to access hospital care39, caretaking roles and family commitments, which are prioritised over health needs37,43,44,53, the cost for family members to travel to hospitals to support their loved ones51, and a lack of family support in making lifestyle changes45. Struthers et al found that, of 866 research participants, 3.6% reported not being able to access health care due no one being able to take care of the children53. Having access to family in the healthcare journey was described as a priority for Indigenous Peoples, as family members are often responsible for the decision-making of their loved one, are sources of support, are strong motivators for health-related behaviours or are important for knowledge dissemination relating to the health condition and care39,42-44. Quigley et al noted that returning to their community was a priority for rural Indigenous patients51. Articles also reported that rural Indigenous patients value holistic wellbeing approaches in healthcare provision, particularly those with a mental health focus41,42,49.

6. Rural Indigenous Peoples’ differential access to the wider social determinants of health: Eleven articles explored differential access to the wider social determinants of CVD health for rural Indigenous Peoples. Rural Indigenous Peoples experienced poor access to personal transport37,43,44,53, significant work commitments43,51,53, inability to pay for services and travel to services45,51,53, reduced access to health literacy and education44,45,51, inadequate community infrastructure (eg food deserts, poverty and pollution)35,39 and limited access to government healthcare entitlements39. Three articles reported that removal of barriers like transport and healthcare costs improved access to care42,46. Tibby et al described the need for funding systems to move away from traditional referral models (ie general practitioner to specialist referral) and allow direct patient referrals40.

7. Effective interservice linkages and communication: Ten articles described barriers and facilitators associated with healthcare service linkages and communication. Five articles reported effective and timely service linkages as facilitators of service provision. Successful inter-healthcare service communication was described as an enabler of CVD care as it creates efficiencies in service provision, supports implementation of health programs that involve multiple service providers, or it creates better connection between rural Indigenous patients and their healthcare teams (eg outreach teams and cardiovascular specialists)38,40-42,47. Three articles reported inadequate communication between service providers and their patients, leading to a lack of knowledge of condition or poor trust in the healthcare services43,44,51. Articles also reported that services have poor awareness of other heart healthcare services available to rural Indigenous Peoples37,47 and that healthcare services have siloed ways of working and poor interservice communication37,45,47,51, particularly regarding shared care plans and discharge summaries45,51. For example, Thompson et al37 found that poor service linkages had the most impact on the design and delivery of cardiac rehabilitation to Indigenous Peoples in Western Australia.

8. Equity-driven and congruent data systems: Eight articles explored access factors relating to healthcare service data systems. Two articles described system functions and tools such as decision support, referral tools for high-risk patients and tools that allow real-time data entry at remote locations to facilitate CVD healthcare delivery40,50. Six articles described barriers relating to healthcare service data systems, including inconsistencies and inaccuracies in healthcare services collecting data about Indigenous patients, particularly for identifying Indigenous patients38,42,46; inadequate referral systems 46,47; limited and disparate data systems between organisations37,38; and lack of workforce capacity to analyse and report data effectively41. For example, MKTA Ltd reported that, although significant amounts of data were collected, one provider was unable to find the time to collate and produce reports with detailed outcomes and analyses due to capacity and capability issues41.

Te Tiriti o Waitangi Framework Principles

Table 2 shows the categorisation of the key driver themes under each of the Te Tiriti o Waitangi Framework principles. Themes were categorised based on the extent to which the findings within each theme addressed any components of the principle. For example, the principle of tino rangatiratanga speaks to Indigenous Peoples’ self-determination in the design, delivery and monitoring of healthcare services. Theme 1 (‘Input from rural Indigenous Peoples on healthcare service design and delivery’) explores the lack of involvement of Indigenous Peoples in healthcare service design and delivery. Therefore, theme 1 has been categorised under the principle of tino rangatiratanga. Te Tiriti o Waitangi Framework Principles are further explored below.

Table 2: Categorisation of key driver themes with Te Tiriti o Waitangi Framework principles

Tukutuku: a preliminary framework for conceptualising the drivers of equitable access to cardiovascular disease health care for rural Indigenous Peoples

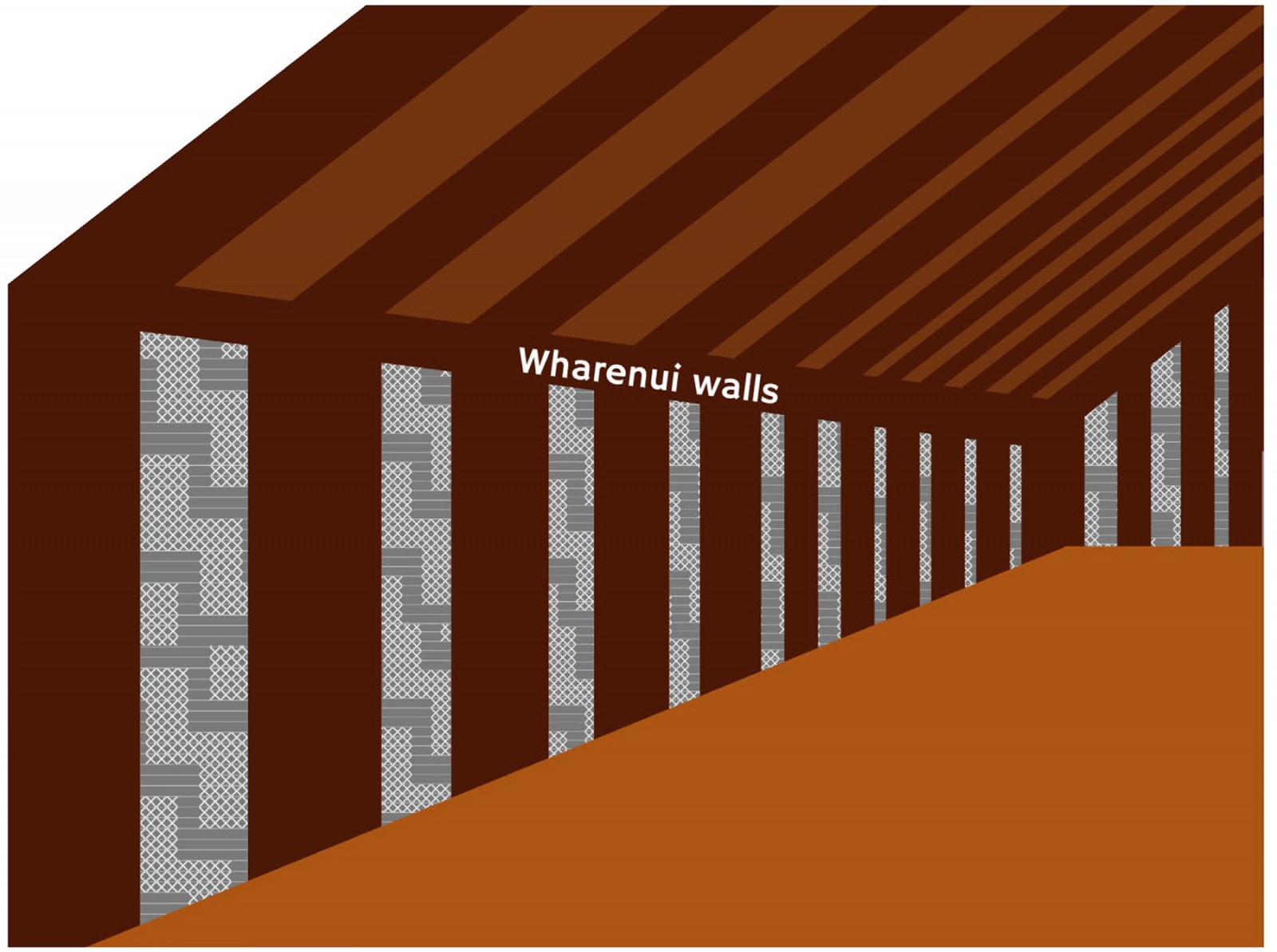

Given the intricate nature of summarising the findings of this review, a tukutuku model was developed by the research team to assist in conceptualising the findings. A tukutuku model has previously been utilised to conceptualise Indigenous health equity58. A tukutuku is a woven lattice panel displayed on the walls of some wharenui (traditional Māori meeting houses) (Fig3). The poutama tukutuku pattern was seen as the most appropriate for conceptualising the findings, as its stepped pattern carries traditional Māori symbolism of genealogies and upward progression through learning59. In this context, the poutama symbolises the upward progression towards achieving equitable access to CVD care for rural Indigenous Peoples. This aspiration may only be achieved by embedding Te Tiriti o Waitangi principles in actions that eliminate the barriers and enhance facilitators to key drivers that influence access to CVD care for rural Indigenous Peoples.

A tukutuku panel is formed by the joining of horizontal and vertical rods, which are knotted together using a cross-styled knot. The vertical rods symbolise Te Tiriti o Waitangi principles. These vertical rods support the horizontal rods, which symbolise the key drivers themes already described. The knots symbolise the connection between the principles and key driver themes, with the aim of that connection being to interact in a way that enhances the facilitators and eliminates the barriers to achieving the aspiration of equitable access to CVD healthcare for rural Indigenous Peoples.

Figure 2: Tukutuku: a preliminary framework for conceptualising the drivers of equitable access to cardiovascular disease health care for rural Indigenous Peoples.

Figure 2: Tukutuku: a preliminary framework for conceptualising the drivers of equitable access to cardiovascular disease health care for rural Indigenous Peoples.

Figure 3: An illustrated example of tukutuku panels in a wharenui.

Figure 3: An illustrated example of tukutuku panels in a wharenui.

Discussion

This scoping review aimed to identify and describe the extent of research into the barriers and facilitators associated with accessing CVD health care for rural Indigenous Peoples. The review found that the barriers and facilitators influencing healthcare access are often two sides of the same coin. For instance, resourcing Indigenous healthcare services was described as a facilitator to accessing care, and inadequate resourcing of Indigenous healthcare services was seen as a barrier to accessing care. Therefore, representing these concepts as drivers was appropriate to ensure cohesive mapping of the barriers and facilitators identified by the literature, by acknowledging that the concepts have the ability to move along a continuum of being a facilitator to being a barrier to care access, and vice-versa60.

The most frequently cited driver was ‘adequate resourcing and support for Indigenous healthcare and rural health services’ (n=17), followed by ‘providing culturally appropriate healthcare’ (n=16), ‘rural Indigenous Peoples’ differential access to the wider social determinants of health’ (n=11), ‘effective healthcare service linkages and communication’, ‘rural Indigenous Peoples’ access to family and wellbeing support’ (n=10), ‘equity-driven and congruent data systems’ (n=8), ‘input from rural Indigenous communities on health service design and delivery’ (n=5) and ‘addressing systemic racism and historical trauma’ (n=3). Most of the drivers elucidated in this review have been previously identified as important characteristics to Indigenous healthcare access in other health contexts (ie culturally appropriate care, community participation, family support and holistic approaches) or for healthcare access in rural communities (ie service linkages and communication, community connectedness and rural health service infrastructure)61-65. The findings of this review offer a broadened understanding of healthcare access for Indigenous Peoples by mapping the distinctive factors that influence access to CVD healthcare for Indigenous Peoples who live in rural or remote communities.

The findings of this scoping review are consistent with other existing literature exploring factors that influence access to health care and health inequities in rural Indigenous Peoples in colonised nations. Some consistencies include the need to eliminate systemic racism and enhance access to culturally appropriate services65-67; the need for appropriate resourcing of Indigenous and rural healthcare services68,69; the importance of community engagement, utilising local knowledge in program implementation and integrated data systems in healthcare service delivery66; family support and involvement in the healthcare journey69,70; understanding and addressing the wider social determinants of health68,71; the ability of Indigenous healthcare workforce to build trust and positively engage with their communities; the need for more support, training and development of Indigenous healthcare workforce67; provider and community relationships built on trust and respect72; and the need to enhance service provider communication with patients and communities68,69.

Alignment with Te Tiriti o Waitangi Framework principles

The Te Tiriti o Waitangi Framework provides a platform for holding the Aotearoa New Zealand healthcare system to account, by articulating the responsibilities and commitments of the healthcare system to Māori, when addressing Māori health outcomes20. It is therefore important to utilise these findings to propose actions that may be needed to address key drivers of CVD healthcare access for rural Indigenous Peoples, and to better align healthcare systems with the principles of Te Tiriti o Waitangi. By using equity-and-rights-based foundations (eg Te Tiriti o Waitangi) to tackle inequities in CVD healthcare access, healthcare systems may be better positioned to achieve equitable access to CVD health care for rural Indigenous Peoples.

Tino rangatiratanga: To better align with the principle of tino rangatiratanga, the findings suggest that healthcare systems must address the need for more rural Indigenous community input in designing and delivering CVD healthcare services.

Equity: The findings suggest that several actions are needed to better align with the principle of equity. First, to ensure that healthcare services are equitably accessible and funded, healthcare systems should commit to adequately supporting and resourcing Indigenous and rural healthcare services. Healthcare systems should also commit to publishing Indigenous healthcare guidelines and ensure healthcare service providers know of and actively utilise these guidelines. Healthcare systems should effectively implement localised Indigenous health programs and ensure that healthcare service providers support their staff in delivering such programs through adequate and ongoing training and development. Second, to assist in eliminating barriers that may contribute to health inequities, healthcare systems should commit to developing culturally tailored and localised educational materials, actively recognise and support the healing of historical trauma in Indigenous Peoples, commit to eliminating cultural incompetence in mainstream healthcare services, enhance access to the wider social determinants of health for Indigenous Peoples and enhance shared care coordination by addressing shortfalls in interservice communication and linkages. Third, to guarantee freedom from discrimination, healthcare systems should commit to eradicating systemic racism in healthcare service treatment and build relationships with Indigenous Peoples based on trust and respect.

Active protection: The findings suggest that the following steps are needed to reflect the principle of active protection. First, to ensure the provision of culturally appropriate services, health systems should commit to providing culturally appropriate care in mainstream healthcare services, ensure the availability of culturally tailored and localised education materials and ensure adequate cultural training of mainstream healthcare staff. Second, healthcare systems should target additional resources to adequately support Indigenous healthcare services and workers, enhance rural Indigenous Peoples' access to the wider social determinants of health and address barriers that limit access to family during rural Indigenous Peoples' healthcare journeys. Third, healthcare systems should ensure that healthcare services collect data about Indigenous Peoples accurately and consistently to keep informed on Indigenous health needs.

Options: To align with the principle of options, the findings indicate that healthcare systems need to support Indigenous Peoples better in choosing their own social and cultural path by supporting Indigenous healthcare services and workers, enabling access to family and community in the healthcare journey and ensuring that healthcare services offer holistic wellbeing approaches. To ensure culturally and medically responsive mainstream and Indigenous healthcare services are equitably maintained and available to rural Indigenous Peoples, healthcare systems should protect the availability of rural and Indigenous healthcare services, support multidisciplinary healthcare teams and offer holistic wellbeing approaches.

Partnership: The findings show that some measures are needed to reflect the principle of partnership more sufficiently. To ensure rural Indigenous Peoples are not subordinate or disadvantaged, healthcare systems should increase awareness of Indigenous healthcare services within mainstream services, adequately resource Indigenous and rural healthcare services, and effectively implement Indigenous healthcare guidelines, localised Indigenous health programs and culturally tailored educational materials. Health systems should also encourage equity-driven and congruent data systems and support health services to provide effective and timely communication with rural Indigenous patients. Healthcare systems should also adequately resource and support Indigenous healthcare services and healthcare workers so Indigenous Peoples can manage their own affairs in ways that align with their own customs and values.

Knowledge gaps and implications for future research

This scoping review highlighted several knowledge gaps in the literature. First, there was a lack of literature exploring rural Indigenous community input in the design and delivery of CVD healthcare services, with only two articles addressing this driver. This is a significant gap to highlight, given that existing evidence shows that community involvement in the design, delivery and evaluation of healthcare services positively impacts health outcomes and community empowerment across health service levels, community levels and individual levels73. Furthermore, the literature in this scoping review that did describe community input in CVD healthcare services omitted the monitoring aspect of healthcare service delivery. The omission of evaluative components associated with community involvement in healthcare service implementation is consistent with existing literature, which reports a need for a more robust evaluation of community participation initiatives72,73. A lack of Aotearoa New Zealand literature was also identified in this scoping review. Only one identified article was from Aotearoa New Zealand. This may demonstrate a need for further research on access to CVD health care for rural Māori in Aotearoa New Zealand. Given that none of the articles included in this review met all the criteria for the CONSIDER statement, future research in this area needs to ensure that research conduct supports health equity and strengthens research with Indigenous Peoples.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this review. First, it is important to acknowledge that not all literature on this topic may have been identified during the research process. One study by Harwood et al, which was published after the search, explored barriers to optimal stroke services for rural Māori in New Zealand69. Harwood et al’s findings included the need for enhancements in provider communication, involving the family in the care journey and improving access to stroke services for rural Māori69. Second, while the inclusion criteria of this review did enable the identification of a diverse range of literature, restrictions relating to CVD conditions and barriers and facilitators reported only by Indigenous Peoples and health service providers themselves meant that other potentially related conditions (eg type 2 diabetes-mellitus) or barriers and facilitators reported by researchers were omitted. Third, rurality classification systems in Australia include the term 'regional centres', which represents non-metropolitan areas74. Although the majority of literature identified was from Australia and the search terms used to describe rurality in this review included ‘rural’ and ‘remote’, Australian literature that exclusively used the term ‘regional’ may not have been identified. More information on this limitation and others pertaining to the protocol of this scoping review is published elsewhere32.

Conclusion

This review has identified literature that speaks of several diverse barriers and facilitators to CVD healthcare access for rural Indigenous Peoples that often represent two sides of the same coin and are reframed in this review as 'key drivers’. The findings are consistent with other literature identifying drivers to healthcare access for rural Indigenous Peoples. This review provides a new approach to summarising the literature by situating the themes within a framework of equity and Indigenous rights: Te Tiriti o Waitangi. This review highlighted the need for further research to be conducted in the context of Aotearoa New Zealand. The findings of this review will be used to inform a mixed-methods study aiming to understand the key drivers that influence CVD healthcare access for rural Māori in Aotearoa New Zealand and to develop practical recommendations for solutions that enhance equitable access to CVD health care for rural Māori from a Te Tiriti o Waitangi standpoint.

Acknowledgements

This systematic scoping review was funded through the University of Auckland doctoral scholarship and a grant jointly awarded by the Heart Foundation of New Zealand and Healthier Lives National Science Challenge (grant number 1819).

References

appendix II:

Appendix II: The CONSIDER statement for strengthening the reporting of health research involving Indigenous Peoples